Banded Together

These four brothers, separated by nearly a generation, say there was one doctrine their father baked into all their kishkes: a hatred for falsehood and a love for honesty

As I drive into New Square — the first fully chassidishe village in the United States — and pull up to a small house on the left, it’s hard to imagine a family of 14 once fitting between its walls. The house, similar to other structures in this village of about 8,000 residents, is no mansion. A small kitchen, its refrigerator adorned with pictures of the eineklach and pithy sayings, has a table with four places.

This structure — which served as the first location of the Skverer cheder — is the house in which Reb Reuven and Shifra Schmelczer built their family and raised a dozen children. Now some of those sons have gathered together in their childhood home to reminisce about the past, marvel at how far they’ve come in life, and put their own challenges and journeys into the context of loving parents who tried valiantly to maintain the strictures of the shtetl in a new world of open opportunities, while providing love and security even as their children made their own choices.

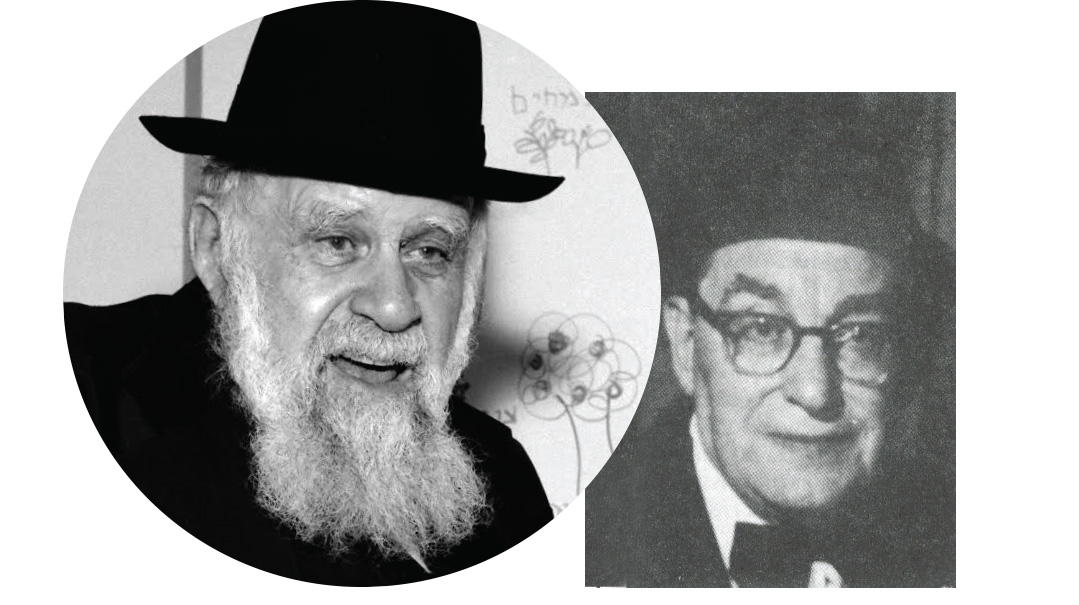

These four Schmelczer brothers, Zishe, Aaron (who joined from Montreal via Zoom), Lipa, and Velvel — two pairs from almost separate generations — might have different natures, but are still a close-knit clan.

Zishe, the third oldest at age 59, is the only one still living in New Square. An acclaimed chassidishe mechanech who educated a generation of children with over two dozen tapes and CDs, Zishe now works as a fundraiser for a variety of causes including the Skvere mosdos. He refused to look at the flickering computer screen even as he joked with Aaron. Zishe, who has developed an array of antics to elicit donations, described his goal in life as “making people smile.” A gifted singer himself, he recalls how the previous Rebbe, who was niftar in 1968, encouraged him to sing as a child and rewarded him with a sugar cube or money.

“Hey,” says Aaron, the next child after Zishe, “Now I find out now that you were an ashir already then? How come I didn’t get any money?”

But Aaron (the brothers affectionately call him Ari) has only praise for his brother Zishe, relating how he’s devoted his life to charity and making the world a better and happier place.

“He really does put a smile on people’s faces,” Aaron says. “Dancing, singing, entertaining, this is his whole life.”

Oops! We could not locate your form.