Articles of Faith

In 1944 Reuven Chaim Klein buried a collection of silver family heirlooms under a house in Munkacs. Decades later, this small treasure trove was unearthed — tarnished and bent, but miraculously intact.

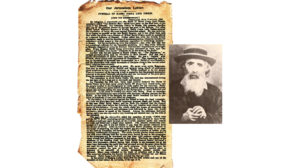

The Klein family shares the story of the family heirlooms that they once treasured; buried and gave up for lost, and ultimately recovered. From left to right: Yitzchak Klein, his brother Reuven Chaim, and Yitzchak’ son, Elozar. In the foreground: the family’s beloved Shabbos candlesticks – a gift from Reb Shayele Kerestirer ztz”l (photos: Judah Harris)

I

t was an especially joyful gathering for the Klein family of Boro Park and Flatbush. The occasion was homecoming of sorts — not for a young woman returning from a year of seminary or a bochur from a year in a faraway yeshivah — but for a group of long-lost once-beloved candlesticks and other silversmith’s wares.

The family’s joy at recovering its long-lost treasures was so great that they couldn’t wait to share it with the rest of Klal Yisrael along with the lessons in bitachon and emunas chachamim that emerged during their quest. The very next week they invited Mishpacha to hear their fascinating story told by the very family members who first helped hide the silver and who then sixty-seven years later uncovered the buried treasure.

Brothers Reuven Chaim and Yitzchak Klein born a year and a half apart are both short slight and bli ayin hara exceptionally spry for men almost ninety years old. The external similarities end there. Reuven Chaim clean-shaven and spirited loves to talk bubbling with stories that stream out one after the other. Yitzchak the younger brother has a short gray beard bright blue eyes and a warm manner. He is content to let his older brother do the talking.

We meet in Yitzchak’s apartment in Boro Park a small immaculate space that still bears the imprint of his late wife. A modest breakfront is filled with silver and knickknacks. A side table proudly brims with photos of several generations of Kleins. Yitzchak’s son Elozar has joined us to help tell the story in which he himself was a major player.

Reuven Chaim and Yitzchak are bona fide Munkacser chassidim. Both were born and raised in Munkacs. Their family’s rebbe was the holy Minchas Eluzar Rav Chaim Elazar Spira zy”a who served as the Munkacser Rebbe for some twenty-five years until his petirah in 1937. Despite the disruption of World War II they maintained their family’s connection to Munkacser Chassidus after arriving in the US. Yitzchak who once owned a successful factory to this day dedicates himself fully to the service of the present Munkacser Rebbe helping wherever he can.

For the purpose of this story Reuven Chaim and Yitzchak Klein trace their family history as far back as their grandfather an outstanding talmid chacham named Reb Hersh Ber (Tzvi Dov) Klein.

“He was mesayeim Shas five times” Reuven Chaim relates proudly waving a finger in the air. “His house was in the center of town. People walking by would see him standing and learning by his shtender for hours at a time. At that time not so many people used a shtender to learn. He was a businessman too; he had a glass factory.” Reb Hersh Ber served both as a melamed in the talmud Torah and as the rosh kahal of the Munkacs Jewish community under the Minchas Eluzar and prior to that under his father the Darkei Teshuvah zy”a. “He knew the Minchas Eluzar quite well ” adds Reuven Chaim.

Hidden Human Treasure

Reb Hersh Ber had several children – one of whom – Moshe Ezriel is relevant to our story. Moshe Ezriel’s brother was married to the daughter of the Kerestirer Rebbe, Reb Shayale, who was renowned in Munkacs as a baal mofes, a wonder-worker.

About 1915 or 1916 (here the brothers debate the date briefly), young Hungarian men were being conscripted to the army for World War I. Reb Hersh Ber, fearing for Moshe Ezriel, consulted the Minchas Eluzar for an eitzah. “Why did you come to me?” the Minchas Eluzar retorted. “You have a mechutan!”

Reb Hersh Ber understood this to mean that he should take Moshe Ezriel to his mechutan -- Reb Shayale. The Kerestirer Rebbe’s family decided to hide Moshe Ezriel until after the war. Around 1917, Moshe Ezriel married Frida Rifka Kahan, with Reb Shayale as the mesader kiddushin. As a wedding gift, the Kerestirer Rebbe presented the couple with a pair of large silver candlesticks and a silver becher.

The couple had three children: a girl, Maytu, then Yitzchak and Reuven Chaim, our interview subjects. The two were aged three years and eighteen months, respectively, when their mother Frida Rifka tragically passed away in 1924. A year later, Moshe Ezriel married again, this time to Leah Malka Steinmetz. Five more children, and five more candlesticks, were added to the family.

“I don’t know if they could afford to buy new silver leichters every time they had a child,” Reuven Chaim says. “We do know that eight silver ones were buried and survived the war, but the family would have been lighting ten candles every Shabbos.”

Winds of War

The Kleins describe prewar life in Munkacs as idyllic. The Minchas Eluzar once commented that everything in Eretz Yisrael is better than Munkacs, except the luft (air).

“The fresh air was very conducive for staying awake when learning!” comments Elozar Klein, Yitzchak’s tall, jovial son. “The Carpathian Mountains descend from Poland into Munkacs, and even the non-Jews would come for the wonderful mountain air.”

There were Jews in the Munkacs area for at least 250 years before World War II, a mixture of Galician and Hungarian Jews. A large yeshivah was in operation by 1851.

“Munkacs had become a Jewish town because there had been a poritz [landowner] who was kind to the Jews,” Elazar says. “Munkacs was actually 50 percent Jewish in the decades around the turn of the twentieth century, out of a population of 30,000 to 40,000. No other town in prewar Europe had such a large percentage of Jews, and there were excellent relations between the Jews and the non-Jews.”

Under the leadership of the Minchas Eluzar’s grandfather, the Shem Shloime, Reb Shlomo Spira, zy”a, the Munkacser chassidim purchased and constructed an entire hoif. The complex of buildings included a shul, a beis medrash, and a permanent succah that doubled during the year as the office of the Rebbe Meir Baal HaNess tzedakah fund. The Minchas Eluzar himself, according to Elozar, was “the posek for the ten cities around Munkacs — he was the gadol hador. At one point the Belzer Rebbe considered making his home in Munkacs, but never followed through because the Minchas Elazar insisted that the city could only have one beis din and one shechitah.”

The spiritually rich (if materially modest) Jewish life of Munkacs was not destined to last. Hungary was one of the last countries in which Jews were herded off to the concentration camps; nevertheless, by 1943 it had a ghetto, and the men had begun to be dragged off to labor camps. By then, the destruction being wrought on the Jews of Europe was well-known.

“Around that time, a group of about a hundred Polish Jewish children wandered into Munkacs,” Reuven Chaim recounts.

“Their parents had been rounded up by the Hungarians as illegal aliens and deported to the death camps,” Elozar interjects. “They were hungry, shocked, many of them barefoot. My uncle was moser nefesh to save them. He could have gotten arrested if he was caught — he was on a most-wanted list! In fact, they came to grab him on that Rosh HaShanah. The rav had been warned, and he forced him to leave the shul. He grabbed the machzor out of his hands, and told him, ‘Go hide! I’ll daven for you!”

Surviving the Ghetto

The Klein family set to work to provide food, shelter, and care for the refugee children.

“That summer, we made a day camp for the local children,” Reuven Chaim says. “We would mix the Polish children in with them, and nobody noticed. At night, we would take them to a lumber yard in the forest and hide them there. We would bicycle out there with meals for them. We had a neighbor, Mrs. Farbenblum, who along with our sister Maytu used to cook those meals.

“They also cooked for the poor of the community, from a kitchen in the shul. Most of the men had been taken to labor camps or the army. Women whose husbands had a store could still sell off the goods to get money, but the others had no source of income. So we opened up a soup kitchen. A few of the boys would go around collecting money for them, but as time went by there were more and more people and never enough money.

“We made a larger committee; the soup kitchen was turning out 1,800 portions a day, with some help from organizations in Budapest. At night, we’d deliver packages to people who were too embarrassed to pick them up themselves, as well as envelopes of money, matan b’seser, to those in need.”

During the winter nights, they would leave the beis medrash windows open, and the Polish children would climb in to eat and sleep. At dawn, they’d disappear.

“We were eventually able to put these children on a train to Budapest and then send them on to Israel. Some of them became important rabbis and army generals,” Reuven Chaim says.

During these months of ghetto life, Mrs. Farbenblum (the valiant, apparently indefatigable cook) mentioned to Reuven Chaim that she was planning to bury her good silver at her father-in-law’s house. Reuven Chaim asked if he could be part of the plan. He and his half-brother Shaya put the smaller silver items, like salt shakers and cutlery, into a large glass jar, and wrapped the candlesticks in brown rags. Together with the Farbenblums, they buried all the silver in a hole about two feet square and one foot deep under the floor of Mrs. Farbenblum’s grandfather’s house on the other side of town. There was no time to dig a deeper hole. Jews were being deported, and Yitzchak was by then already in a labor camp.

Shortly afterwards, Adolph Eichmann, yemach shmo, arrived in Munkacs.

“The Munkacser Rebbe, shlita, has seen the log books — when Eichmann signed in and out. He was only there for about twenty-two minutes, but in that short space of time he gave exact instructions on how to build the ghetto, how many trains would be needed for transporting prisoners in and out, how much personnel would be needed,” Reuven Chaim says with obvious bitterness.

He himself was soon deported to Auschwitz, and during the remaining eleven months of the war he served time in five different concentration camps. “Five,” he emphasizes, counting them off on his fingers: “Auschwitz, Dora, Buchenwald, Bergen-Belsen, and Eldritch.”

At Dora, about a hundred kilometers from Nordhausen, Reuven Chaim was put to work building a bomb factory on the inside of a mountain.

“We’d make about twenty holes, six feet deep, into the mountain, and then we’d dynamite the holes,” he recounts. “Then we cleared out the stones by hand. When we were finished, we’d be coated head to foot in white dust from the blasts.

“The Americans were stupid!” he scoffs. “They were afraid to bomb the camps, but they could have bombed the electrical generators, and the water and gas supplies. All those things were always located outside the camps.”

When the war ended, Moshe Ezriel and his children Yitzchak, Maytu, and Riftchu went back to Budapest.

“They knew that the family’s silver had been buried somewhere in the town,” Elozar says, “but only Reuven Chaim and Shaya knew where it was.”

However, there was no time to try and retrieve it. A few weeks later, a Jewish Soviet officer warned the family that the Red Army was planning to move in the following Tuesday, and would close the borders. “You should run,” he told them. “Communism isn’t an environment for frum Yidden like you. I’d leave myself, if I wasn’t worried about what would happen to my family back in Russia.”

The family packed their bags and left for Budapest that Motzaei Shabbos, intending to go to Israel. But by the time they arrived in Budapest, the British had closed the borders of Palestine; they went instead to a DP camp in Austria, where they knew Shaya was staying. From there, the family made its way to America.

The Breakthrough

The Klein family replanted itself and flourished in democratic America, while their beloved Hungary fell under Communist control. From 1956 to 1998, they had little to do with their native land.

In 1998, some time after the fall of Communism, several Munkacser chassidim urged the Rebbe to make a pilgrimage back to Munkacs in honor of the sixtieth yahrtzeit of the Minchas Eluzar. A plane was specially chartered for 180 Americans, and more than 200 people from several countries gathered together in Munkacs.

“While the Communists were in power, the old hoif had been occupied by the Soviet army,” Elozar explains. “You couldn’t get in without an Intourist guide. They wouldn’t let anybody take pictures. Now it belonged to the local police, and we had no access to the buildings. We could only set up a tent, and be mispallel at the tziyun.”

A wealthy Munkacs-born businessman, Alexander Rovt, whose real-estate fortune has earned him a place on the Forbes list of the 400 wealthiest Americans, had accompanied the group and used his influence to help open doors

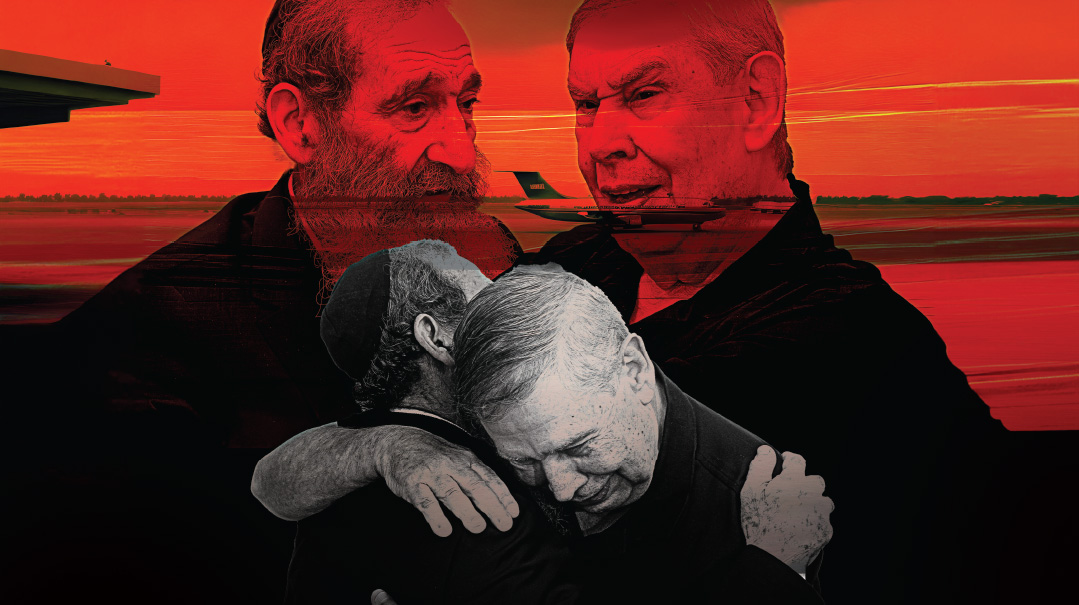

The Munkacser Rebbe shlita (left) and Alex Rovt (right) with Yitzchak Klein. The Rebbe’s advice and Mr. Rovt’s shtadlanus in following that advice was indispensible in the recovery of the items

“He [Rovt] promised the Rebbe, ‘If you come back, I’ll make a hotel here for you, with a pool, air conditioning, everything!’” Elozar recalls. “And he was as good as his word. Today there’s a beautiful hotel there. But even more importantly, Alex has been working with the Rebbe since then to rebuild the entire hoif, including a new beis medrash where daily minyanim and shiurim in Mishnayos are held, and a kosher kitchen and restaurant that serves 200 meals a day.”

Prior to this 1998 Munkacs trip, Reuven Chaim happened to mention to his nephews, Elozar and his brother, that he had hidden silver during the war in a house in Munkacs. The brothers, excited by the idea of recovering family heirlooms — some of which had been a gift from Reb Shayale Kerestirer — wanted to see the house right away, but on that trip there was no time. It was only several years later, on a longer visit to Munkacs, that they were able to see it. Reuven Chaim also went along, and took a cab with them to the house where the silver was buried.

Having finally located the house, they began discussing how they might go about getting access. Finally, as true Munkacser chassidim, they went to the Rebbe for direction.

“He told us to ask Alex Rovt what to do,” Elozar says. “So we did, and Alex suggested that we simply buy the house. At the time, it would’ve cost us five thousand dollars. My uncles and my father had a meeting, but we finally decided against it. Uncle Shaya told us that the non-Jews knew that Yidden had buried stuff, and it was quite likely that someone had dug it up already, or that it had corroded over time. In the end, we realized we should have followed the Rebbe’s advice all the way!”

This became quite clear on a subsequent trip. The economy of the Ukraine had improved dramatically, partly due to international investment. They found that the house had been bought and renovated, and was now valued at close to $50,000.

“We didn’t have much time to do anything. The Rebbe doesn’t like to be away for Shabbos, so his trips to Munkacs are usually short, just Sunday to Thursday,” says Elozar, who along with his father, are often zocheh to accompany the Rebbe on these short trips to daven at kivrei avoseinu. “So the matter was dropped for awhile.”

“Then, about two years ago, my father again got the urge to try. He went back to the house with Alex’s assistant Frankie, and knocked on the door. The lady who answered the door was very welcoming,” says Elozar.

No one mentioned the motive of their visit; but for his father, it was a “scouting”

mission. The lady of the house and her husband had added a third room to the back of the original structure, but the original rooms were just as they had been before the war.

“At that time, my father did not notice that the addition had closed up a window on what had been an exterior wall. This was important, as that window was our guidepost as to where the silver was buried. Still, they left the house with a real cheishek to do something.

“It was another two years until the Rebbe, Alex, and my father were all in Munkacs at the same time, and we all had the chance to discuss the matter again. A few different ideas were discussed. We turned to the Rebbe and he picked the simplest plan. Alex would have to be involved personally. Though he is a person who is used to giving the orders, when the Rebbe asks him to do something, he drops everything and jumps to help,” marvels Elozar.

“He followed the Rebbe’s directives to a T, even though he had other ideas of how to go about it, and doubted the chances of our recovering anything. The plan was to return to Munkacs, and explain to the current owners of the house that during the war, some items of sentimental family value had been hidden somewhere in the house, and that we would like to bring a good contractor with us to help us locate them. We actually had a contractor already; the one who was working on the beis medrash. ‘Today he won’t be working on the beis medrash, he will be working for Mr. Klein,’ said the Rebbe.

“Alex was to go along with them, putting his personal reputation on the line as a guarantor against that everything would be replaced as it was before. The woman of the house said she was agreeable, but that she would have to ask her husband when he returned home from work.

“At eight that night,” says Elozar, “we got the call that they both agreed. The next morning, my father, Frankie and I met the workers at the house. The man of the house had taken the day off from work. In fact, he even helped us dig!”

Because the window demarcating the burial spot had been closed and plastered over when the house extension had been built, Elozar and his father Yitzchak had a hard time estimating where exactly to begin digging. They chose a spot and began to dig. After an hour’s labor, they had found nothing.

“Even the owner of the house was getting worried,” Elozar says. “He was afraid we would just leave without fixing the mess we made. My father was also ready to give up. ‘Elozar, we gave it a shot; we tried. It’s just not there.’ The workers had even started putting some of the dirt back into the hole. I couldn’t give up that fast. I figured we were just off by about a foot or two.

‘Who says the window was in the center of the wall? Maybe it was a little to the right?’ I called the Rebbe, and he told us to try some more — he even offered more money to dig more. The workers reopened the original hole, starting taking off a few more floorboards to the right, and began digging there.

“Ten minutes later, we found them,” Elozar says incredulously. “I cried when I saw that first candlestick come out. I shouted for my father to come in — he had been outside in the back yard. He picked up the candlestick, and he cried too.”

The workers pulled a cache of candlesticks — eight in all, plus silverware — from the hiding place. The smaller silver pieces were still in the original jar in which they had been hidden. The rag that the leichters had been wrapped in had long since disintegrated. The candlesticks were badly tarnished, and some had been bent, but they were all there. One of the candlesticks still had wax stuck to the inside, where the last candle had burned in 1944. The owners of the house looked almost as happy as the Klein family, and Alex and the non-Jewish contractors who had done the digging refused to accept any compensation for their work.

How the silver got out of the Ukraine is another story; in theory, antiques are not allowed to leave the country. Suffice it to say that, in Elozar’s words, “The Rebbe told us not to worry, and he was right. I’m the kind of guy who always gets stopped at customs, but this time, we just sailed right through.”

The silver is now in the process of being repaired and cleaned, little by little. One finished candlestick, still wrapped in cellophane from the silversmith’s, is a gleaming, majestic pillar of silver. Standing there proudly on the dining room table, it bears witness to one family’s faith: the faith that led Reuven Chaim to bury them sixty-seven years ago, expecting to come back and reclaim them; to Elozar Klein’s faith that with enough effort, someday he would find them; to the faith that kept the Munkacser chassidim together over the years and led them back to Munkacs to restore their ancestral hoif. Most of all, the candlestick is a beautiful symbol of faith that our precious Jewish family life will endure till the end of time.

“My daughter Estie summed up our feelings about these ‘articles of faith’ very succinctly,” says Elozar, “when she said, ‘I am alive today here holding this candlestick because of the tefillos that my alter bubbe, great-grandmother Frida Rifka, said every Shabbos and Yom Tov when she lit these licht!’

Contemplating this regal object, we can’t help but ask: “How will you possibly decide who gets what?” One can’t help but think of the lamentable number of family feuds caused by property disputes. How do you decide how to distribute such precious family heirlooms? How about Mrs. Farbenblum’s silver, since she died and apparently left no heirs?

The brothers are silent for a moment, contemplating this question. Then a young married niece, who has been listening in to the interview, pipes up with what is clearly the obvious answer for a family of Munkacser chassidim: “We’ll just have to go and ask the Rebbe!”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha Issue 326)

Oops! We could not locate your form.