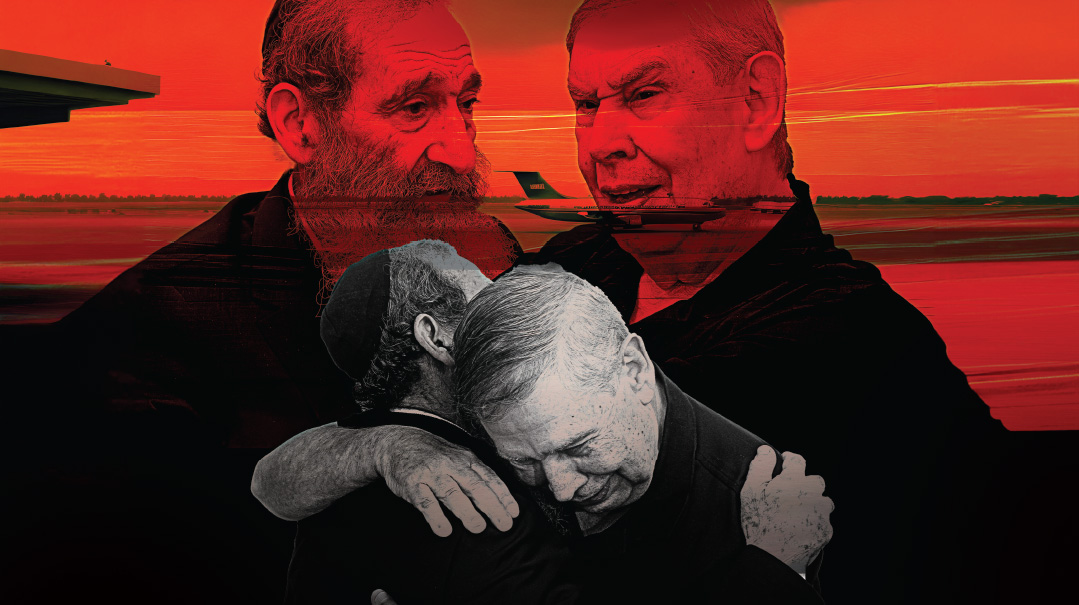

Angels Under Fire

| January 23, 2024The terror and carnage of October 7 couldn’t stop United Hatzalah’s volunteers from heading into the war zone

Photos: ArtScroll/Mesorah Publications, AP Images

On October 7, 2023 — Simchas Torah 5784 — over 1,000 volunteers of United Hatzalah willingly put their lives in danger and entered the war zone to save countless lives under fire. Miraculously, every single one of the volunteers who drove down south that morning returned home alive. Each one of the “angels in orange” has a story, and those stories are now being shared in a soon-to-be-released book

IT

was the most wrenching decision Hatzalah COO Dovi Maisel had ever made. How could he send his volunteers into the war zone when the first rule of emergency aid is to stay out of the line of fire? “I had to do it,” he told me, noting that the other national emergency crews were told not to enter any live-fire situation. “I had to allow them to go and save Jewish lives. Because that’s what we do.”

By Motzaei Yom Tov of Simchas Torah, the rest of us learned that Hamas had attacked the country from the air and the sea and through the border fence. We learned that they had gone from kibbutz to kibbutz slaughtering anyone they were able to kill, and that they had taken hundreds of hostages. We learned that they had attacked the people who had attended a music festival near Kibbutz Re’im.

We learned that they had infiltrated the cities of Sderot and Ofakim.

And we understood that something happened on that day that had changed the world as we knew it.

During the first week of the war, I was contacted by United Hatzalah founder Eli Beer, who was still reeling from the incredible mesirus nefesh of his national team of Hatzalah volunteers. Eli knew it was a story that had to get out, and so, I picked up the gauntlet. I put everything else in my life on hold as I began interviewing the volunteers who had gone down south to save the lives of their fellow Jews, without weighing the pros and cons of their own safety.

And so emerged the story of the angels in orange.

Angels in Orange is a book about one never-to-be-forgotten day — a day that displayed both the best and the worst of mankind, about human animals and modern-day heroes. And most importantly, about the kind of ahavas Yisrael that sends people to a war zone to save a Jewish life.

Amazingly enough, the Master of the World rewarded this incredible group by making sure that every single volunteer who traveled down south to save lives lived to tell the story.

Some were shot at; others encountered terrorists; one was almost crushed by a tank. But every one of those heroic tzaddikim somehow made it home alive.

Three months into this war, the collective memory of those first days starts to get fuzzy, even as it’s become clearer than ever that little makes sense according to the rules of nature: It doesn’t make sense that the army ignored the intensive training exercises that Hamas was conducting on the Gaza beaches just across the border — in full view of Israel — even though the soldier lookouts kept warning their higher-ups about the maneuvers. It doesn’t make sense that a billion shekels of hi-tech was breached by a few tractors, or that there was an utter collapse of one of the most advanced military and security establishments in the world, capable of pinpointing and liquidating enemies around the globe, yet utterly blinded on that dark day.

And it doesn’t make sense that during the early hours of Simchas Torah morning, there was a very limited police presence on the highways between the southern city of Sderot and the rest of the country, and had the terrorists continued onward, as was their initial plan, they might have swept through the countryside reaching all the way to Jerusalem. Instead, they killed, tortured, maimed, stole, kidnapped, and kept themselves occupied committing unfathomable evil — too busy to continue onward even though the roads were open and they could have gone anywhere they wanted.

There are countless stories of other such miracles. Stories of terrorists shooting at people at point-blank range — and nothing happened to them. Stories of terrorists choosing one particular person and telling them to run — allowing them to live for no apparent reason.

So many miracles and so much pain — side by side.

None of us likes reading about massacres and murder, yet that is exactly what happened to our nation. Not in the distant past. Not 1,000 years ago. Not 500 years ago.

Now. In our time. To us. And we need to know what happened to our brothers and sisters in Eretz Yisrael on Simchas Torah 2023.

BY the time Simchas Torah ended, United Hatzalah had sent 1,700 volunteers into the war zone. When they realized that they were going to run out of ambulances, the order was given that any volunteer who was determined to go down south should take his own car. In normal times, it’s illegal to transport patients in regular cars, but these weren’t normal times.

When initial reports started trickling in, it seemed to United Hatzalah founder and leader Eli Beer that around 400 terrorists were rampaging through the south, and that the army was having a difficult time getting its troops to where they needed to be in order to combat the threat. Had Eli known that it was actually more like 3,000 terrorists who had infiltrated the country, including many Gazan “citizens” who followed the Nukhba troops across the border with knives and axes, he is not at all sure that he would have allowed his volunteers, or his own wife, to head to the war zone.

“We told our volunteers to count the number of dead people they were seeing,” Eli says. “But the numbers we were getting didn’t seem real. They couldn’t be real. How could it be that there were 40, 50, 60, 70, 100 people lying dead in their cars in one small strip of highway in Israel? How could it be that so many innocent civilians had been murdered and their bodies abandoned?”

Little did they imagine that the number of dead was going to amount to well over 1,200, while thousands of others would be wounded and hundreds would be kidnapped and held hostage. Who could have imagined that Hamas terrorists were running around executing Jews in the streets and, even worse, in their very homes?

It was unthinkable, and yet it was happening. And this is the story of those brave men and women who didn’t blink, who didn’t make personal calculations as they somehow found themselves in a bubble of Divine protection while racing on to their holy mission of rescue.

Note: Some of this material might be disturbing to sensitive and young readers and not in the spirit of Shabbos. Reader discretion is advised.

Into the Battle Zone

The following are excerpts from the soon-to-be-released ANGELS IN ORANGE: Uplifting Stories of Courage, Faith and Miracles from the United Hatzalah heroes of October 7th (ArtScroll/Mesorah), by Rabbi Nachman Seltzer

ON MY WATCH

CHARLES GROS, a volunteer for Hatzolah in New York, was visiting Israel from New York for Succos, like so many other Americans. The last thing he expected was to be caught in a war

I was in my room in the David Citadel on Simchas Torah morning when I heard a noise. At first, I wasn’t sure what it was, but then I heard the loudspeaker of the hotel kick in, and a voice said, “All guests in the hotel, please make your way out of your rooms and into the fortified stairwells.”

I left my room, and as I was walking down the hallway, I ran into United Hatzalah founder Eli Beer and his son-in-law.

“It’s bad,” Eli said. “Come help us.”

The next thing I knew, we were driving with lights and sirens on, pulling up outside the United Hatzalah headquarters.

The first thing I saw was a dispatcher on the phone with someone down south who had been shot in the leg. It was clear that events were moving rapidly. A few minutes later Eli informed me that the decision had been made that volunteers would be able to transport patients to the hospital in their private cars. He explained that this had never been done before.

Turning to me, he said, “Are you ready to go down south?”

Eli pulled over a guy named Avi, who was carrying a gun.

“Avi is going to be your driver,” he said to me. “He’s one of the best.”

Missiles were falling around us as we drove further into dangerous territory. There were fires burning where they landed, causing smoke, devastation, injuries, and death. While the Iron Dome was working overtime to prevent as many missiles as possible from entering Israel, the bombardment was too much for the system, and it wasn’t able to stop everything from flying in.

We saw fields on fire and a house burning where it had been struck. There was no question that we were literally driving straight into a war zone. On the way, we were stopped by a nurse and a doctor who requested medical supplies so that they would be able to treat patients who had been wounded in earlier attacks.

Soon we arrived at our first call. A missile had fallen right in front of a building. There were a bunch of cars on fire, and since people were already dealing with the situation, we continued on our way.

I

’ve been a paramedic for over 30 years and have seen many things in my life, but the situation we faced here was absolutely horrific. We passed cars that had been riddled with bullet holes and cars with people inside them who had been killed. Some of the cars on the road were still running, but they were empty.

One of the most frightening parts of the drive was that every time we saw a vehicle coming toward us from the other direction, we didn’t know if it was our people or the enemy. We were getting reports of stolen police cars, stolen ambulances, and terrorists who were disguised in IDF uniforms, so whenever we saw any type of vehicle coming in our direction, both my driver and the other EMT made sure their guns were ready to fire — just in case.

It wasn’t long before we began receiving patients, brought to us by soldiers who had saved them from the party that had taken place not far from the border with Gaza, as well as from nearby moshavim that had been attacked. Soon I found myself in the back of the ambulance with four patients in various levels of pain and injury.

The patient in the worst shape was about 24 years old. He had been shot in both his hands and was lying on a stretcher, doing his best to cope with the pain and agony on the 20-minute drive to the closest hospital. He had put both his hands in the air — in the classic pose of surrender — and begged the terrorist not to shoot. Surrendering didn’t have the hoped-for effect on the terrorist, who promptly shot the young man in both his hands. Though in tremendous pain, the man was doing his best to hold on to his watch — a Patek Philippe with a bright red band. It was clear that he was worried about losing his $100,000 watch, and at one point he said to me, “Please hold on to my watch for me. I trust you.”

I took the man’s treasured watch, and since I already had my own watch on my left wrist, I put the watch I’d been handed for safekeeping onto my right arm. Then I continued treating the injured man.

Another injured patient tried to escape a terrorist by running into a house. The terrorist followed him inside. The injured fellow got on his hands and knees and put his hands up in the air. “Please don’t kill me,” he begged. “My wife and children still need me!”

For no obvious reason, the terrorist decided to spare his life.

“Give me your wallet,” the terrorist demanded.

He handed the Arab his wallet.

“Your phone.”

He handed the terrorist his phone.

Suddenly he heard the sounds of Arabic coming through the walkie-talkie the terrorist was using to communicate with his commanding officers, and the terrorist turned on his heels and left.

When we arrived at the hospital, the doors were opened, and the patient who had been shot in both hands was whisked off the ambulance and into the hospital. By the time I finished briefing the hospital staff on the condition of the patients, the man who had asked me to hold on to his watch was long gone, and the hospital wasn’t allowing people to walk around inside unless they had a really good reason for doing so. I guessed that returning the injured man’s watch didn’t qualify.

The afternoon of that never-to-be-forgotten day found us in the southern city of Ofakim. We set up shop near the police station, where we treated about 50 people who had been mildly hurt or injured but didn’t need to go to the hospital. A little later we received a call to drive to a street where a man had been spotted lying on the ground. When we arrived, we could see that the man, who was dead, was wearing a white shirt and black pants and appeared to have been a religious Jew. Most probably he had been on his way to shul that morning when he was shot and killed by a passing terrorist.

As a member of Hatzalah for so many years, I had long been taught about the concept of kavod hameis — of treating a deceased person with the proper respect. Even if you weren’t able to save his life, at least you were able to give him the dignity they deserved.

How I wanted to stay with this Jew and give him that respect and dignity, but there was nothing I could do for him and there were others who were still alive whom we needed to treat.

“Please forgive me,” I entreated the man on the ground, “and try to understand that I can’t bring you anywhere right now because I have to do my best to save as many lives as possible.” Then I got back into the ambulance, and we drove away.

BANDAGES FROM HAMAS

RABBI CHAIM SASSI of Sderot is the rav of a welcoming shul known affectionately as “Sderot B’Park,” principal of a yeshivah in the city, member of the city’s “kitat konanut” (rapid response security team, made up of civilians), and a Hatzalah volunteer

When I realized that the city was under attack, I took my gun and the bulletproof vest and helmet I’d been given by United Hatzalah and went downstairs to load my ambucycle with all the medical supplies I had at hand. I turned on his radio to hear the dispatcher reporting a bunch of shooting incidents on several streets not far away.

By now, I knew that a band of terrorists was rampaging through the city, so I stayed away from the main arteries and drove through the smaller side streets that the terrorists were less apt to use as they moved from neighborhood to neighborhood. Eventually I reached the entrance to the city, where I heard the sound of gunfire coming from the direction of the nearby gas station.

As I got closer to the scene of the battle, I began to pass car after car where the people inside had been executed with gangster-style shots to the head. Driving onto the main road leading toward the exit of Sderot, I came across a group of policemen and stopped beside them.

“They’re shooting by the entrance to the city right now,” I told them. “Go there right away and close off the area! This way no one will try to drive out of the city and get shot at.”

As I drove along one of the main roads, people shouted at me that a policeman had been shot close by. When I got to the wounded officer — one of the commanders of the Sderot police — I saw that another volunteer medic, Yaakov Bar Yochai, had treated his wound and bandaged it neatly.

On the way to treat the police officer though, I spotted a van parked on the street and intuitively grasped that the van had brought a group of terrorists to Sderot.

I backtracked, got off my ambucycle and carefully approached the van to check whether my assumption was correct. Gun out and ready to shoot, I opened one of the van’s doors and saw a curly black wig lying on the floor. I wasn’t sure what the significance of the wig was, but figured that the terrorists were using wigs as a disguise.

Next, I went around to the back of the van and opened the doors to find myself face-to-face with a veritable arsenal of weapons. The space was filled with RPGs and sniper rifles and all sorts of other military equipment. But I didn’t have time to do anything about the weapons, because I immediately noticed another policeman lying on the other side of the street, who had been shot by a Hamas sniper that was shooting at people from the window of the police station. He could see that the policeman on the floor was still moving, though he had been shot in the hand and back.

“He’s still alive,” I told the other three policemen. “I need you to cover me while I run to his side and bring him back here. As soon as I start running, shoot full blast at the police station. Don’t stop shooting until I’m back here!”

The policemen snapped to attention. Pointing their guns at the police station, they began shooting in the direction of the sniper. While they blasted away, I ran as fast as I could to the wounded policeman.

But seconds after I reached him and began trying to help him up, the sniper shot me in the knee and hand, as shrapnel cut into my jaw. Two bullets were aimed at my head, but the helmet protected me from those lethal shots.

Ignoring the excruciating pain, I threw myself on top of the policeman to shield him from the sniper. Then I dragged him behind a dumpster, where I checked the policeman’s pulse and realized that the chances of him surviving were very low.

Knowing I had done all I could for the policeman, I got to work putting a tourniquet on my own knee, which had all but collapsed and was bleeding heavily, and then I turned my attention to my jaw. Blood was gushing out, and I put on one bandage and another, but I could tell that it wasn’t enough. A little voice in my head suggested that maybe this was a good time to recite Vidui, the prayer one says on his deathbed, but I ignored the voice and chose to optimistically recite Tehillim instead.

I stayed where I was for the next hour and a half, trapped in my spot behind the dumpster because of the flying bullets. There was an officer from the Shabak (Israel’s General Security Services) taking cover nearby who I knew. The Shabak officer promised he’d send someone to rescue me and didn’t stop encouraging me to hold on, until they could take the sniper out and it would be safe for me to move. He didn’t content himself with words, throwing bottles of water that he had with him in my direction, as well as more bandages, so that I could attempt to stem the heavy bleeding.

But even after I applied the bandages, it was clear that I needed more. “I need you to get me more bandages!” I called out to my friend.

“Where from?”

Suddenly I remembered: “I’m sure you’ll be able to find plenty of bandages in the terrorists’ van.”

“What van are you talking about?”

I told him about the van filled with military equipment that I’d seen earlier.

I gave the officer directions to the van, and the officer returned a short while later with plenty of top-quality, sterile bandages — courtesy of Hamas.

Yet when the Shabak officer opened the door of the van and began searching for a first-aid kit, he discovered something else as well as a stash of bandages. Lying on the floor of the van was a radio, the kind the terrorists were using to communicate with one another as they rampaged through Sderot killing and maiming innocent people. The Shabak officer was fluent in Arabic and understood everything the terrorists were saying to one another over their radios.

The officer heard them when they said which floor they were on in any given building, and he knew what they could see and what was out of their line of vision.

From that moment on, the officer listened in on the terrorists’ radio communications and used the information to save many Jewish lives.

Finally, when the sniper’s gunfire ceased, Yaakov Bar Yochai came with his private car to evacuate me to the hospital. A wounded policeman sat in the front seat, and I lay down in the back. Soon an armored vehicle pulled up, and another wounded police officer was transferred into the back seat right beside me. This officer had been shot — he had an exit wound in his back — and he was in bad condition.

I looked at the police officer and saw that the man was bleeding heavily from his back. I knew I had to do something for him before he bled to death. Suddenly I had an idea.

Unwrapping the edge of one of my own bandages, I stuffed it into the hole in the officer’s back, keeping my finger inside the hole and making sure that the piece of bandage didn’t slip out. There was no choice but to hold my finger right there in his back. Otherwise, the blood would have begun spurting out all over again.

An ambulance was waiting for us outside the city. When the medics wanted to move me, I told them that they couldn’t take me out, that I was connected to this police officer, as one of my fingers was in his back stemming the blood.

Somehow, they managed to get the two of us out of the car and into the ambulance, with my finger still lodged in the bullet hole in the officer’s back. The medic helped me remove my finger and treat the wound. I didn’t think the officer would make it, but later I heard that he’d indeed survived.

NO QUESTIONS

Tall, formidable, and fearless, AVI YUDKOWSKI of Givat Ze’ev was a force to be reckoned with on the day Klal Yisrael needed medical volunteers more than ever

I woke up at seven o’clock on the morning of Simchas Torah. My phone was screaming, “Tzeva adom, tzeva adom — Red alert, red alert.” I called Avi Gian, another volunteer who also lives in Givat Ze’ev, and asked him what he was planning on doing. I knew that he had an ambulance that Shabbos and figured that he would probably drive it over to wherever we needed to go.

As we drove toward Gaza, we asked dispatch for instructions as to what to do and where to go.

“Everyone should stay near Cheletz right now,” we were told. The Cheletz junction was being used as a staging area, fairly close to where everything was going on and an easy location for ambulances to reach, but out of the terrorists’ reach.

But here’s what you have to know about my friend Avi Gian: he’s not the type of guy to sit around and wait when he knows that there are people who are injured and dying and need his help.

So we kind’ve ignored the instructions, left Cheletz and headed into the unknown.

There were three of us in the ambulance. All of us were wearing bulletproof helmets and vests. Avi Gian and Emanuel, another amazing medic, were both armed. We hadn’t been driving for long when a car came speeding over to us, motioning to us to stop.

“I have wounded people!” he yelled.

We stopped and helped two girls into the ambulance. They had been at the party at Re’im and were in bad shape. One had been shot in the shoulder and leg. She was also missing a finger. The other had been shot in the hand. We drove back to Cheletz with our passengers and transferred them to another ambulance, then turned around and headed back.

WE took the road to the left, driving on Route 232 — the Avenue of Death. I’d grown up in a regular family in a regular neighborhood. In my wildest dreams, I never imagined that I would see the things I saw on that road. So many cars had been shot at; so many people were dead. It was impossible to process what we were seeing on a normal Israeli highway.

It looked like hundreds of cars had been attacked, and there was nothing we could do for any of them. We kept looking inside cars to see if there were any wounded to treat. But it was clear that everyone was dead, and we were too late to help.

In one of the cars, we saw a dead soldier still holding his gun. We knew that we couldn’t leave the gun in the car, especially when there were still terrorists running around the area.

Avi stopped the ambulance, and the three of us got out. Avi Gian had his gun out, standing guard, while Emanuel and I removed the soldier from his car and loaded him onto a stretcher in the ambulance. Then we got back into the ambulance and drove along the road until we met a few Israeli soldiers.

“We picked up a soldier from one of the cars,” we told them. “He’s no longer alive. Where should we bring him? Where are all the bodies being taken?”

The soldiers exchanged glances. They didn’t know what to say. No place had officially been designated yet for bodies.

The next few hours were a blur of activity. We went back and forth seven times, each time meeting vehicles on the road carrying wounded people who needed to be delivered to the ambulances at Cheletz.

On one of our trips, we were transporting a woman who had been critically injured when terrorists attacked her car and killed her husband. As we drove, the woman kept begging us to promise her one thing.

“Please go back to our car and cover my husband!”

At first, we were reluctant to give our word. There were so many wounded who needed us. But the woman wouldn’t relent, and in the end, we agreed. We took down the license plate and general location of the car and promised her that we would go back to see what we could do.

A

nd then we arrived at the entrance to Kfar Aza.

All of a sudden, an army jeep came flying out of Kfar Aza carrying four wounded soldiers. We loaded them into the ambulance and drove back to Cheletz as quickly as we could. We did this for the next few hours, making trip after trip between Kfar Aza and Cheletz, trying to get the wounded soldiers to the ambulances and helicopters as fast as we could so that they could get to the hospitals in time to save their lives. There was no time to waste. Every second counted.

When we arrived at Cheletz with our wounded soldiers, there were no ambulances left, so we drove them all the way to Barzilai Hospital in Ashkelon. We were about to leave the hospital and drive back to Cheletz when someone banged on the ambulance window. It turned out to be an officer from the Sayeret Matkal, one of the army’s special-forces units.

“My hand was injured a few hours ago,” he said. “They took care of me, and now I need to get back to my team at the front. Can I get a ride with you?”

We exited the hospital and started driving back in the direction of Kfar Aza. The officer put on his helmet. Then he opened the ambulance window, stuck his gun outside, and peered through the sights, on the lookout for the enemy.

“Relax,” I told him. “We already made the drive forty times today. You don’t need to stick your gun onto the highway. None of the terrorists are in this area.”

He looked at us as if we were crazy, telling us how he was attacked right here a few hours ago, and how terrorists were probably still hiding in the trees.

Then the officer received a message on his phone.

“Change of plans,” he said. “I need you to drive me to the police station in Sderot. There’s a gun battle. My team is already there.”

Just like that, we were headed back to Sderot.

Bullets flying in every direction. Screaming. Shouting. Explosions. In the middle of all the craziness, one of the commanding officers approached us.

“I need your help. One of my soldiers was killed a few hours ago, and the body is still lying on the street. Can you help us get him out of the street?”

Taking the stretcher from inside the ambulance, we ran into the street in the direction of the fallen soldier. Running in front of us were three Yamam police special forces, all shooting at the window in the police station from where the terrorists were firing a constant barrage of gunfire.

We reached the fallen soldier, lifted him on to the stretcher, and ran back in the direction of the ambulance.

We brought the dead soldier to a place set up on the side of the road, just as a car stopped us with a wounded man inside. He’s been at the party and had gotten shot in the stomach.

“Take good care of him,” the driver said. “He’s in bad shape.”

We started driving back to Cheletz where a helicopter from Unit 669, the army’s search-and-rescue unit, was waiting. Since there were a bunch of wounded people arriving at Cheletz at the same time, the doctor was going to have to decide who would be flown to the hospital and who would be taken by ambulance.

“Put your patient into the helicopter,” he told us. “The other patient is in much worst condition. The chances of him making it are very low. Your patient should be the one to go by helicopter. At least this way we will be able to definitely save one life.”

As we drove back to Jerusalem after our first day in the war zone, Avi Gian insisted on listening to one song: It was called “Al Abba Lo Sho’alim She’eilot.” We don’t ask questions of our Father.

IMPOSSIBLE NUMBERS

CHEZI ROSENBAUM, who has gone on rescue missions in Turkey and Ukraine, is head of United Hatzalah in Kiryat Malachi. He spent Simchas Torah with fellow volunteer DAVID BADER

Simchas Torah morning, dispatch called to let me know there were reports of gunshots in Ofakim and Sderot, only 20 minutes away from Kiryat Malachi.

My friend David Bader woke up his wife, explaining that there was a situation south and he was needed.

In response to his wife’s question of when he would be back with the family in shul, he said, “Eleven-thirty at the latest. I’ll be back in time for Kol HaNe’arim.”

The people who have made Sderot their home are used to missiles flying overhead and wailing sirens, and don’t scare easily, but that day, it was a whole different Sderot — so many dead bodies lying on the ground. At first we got out of the ambulance and started checking people’s pulses, but it quickly became clear that they were dead, and there was nothing we could do for them.

A little further in, I caught sight of a Toyota pickup truck. There was a group of terrorists standing on the flatbed, rifles in their hands and strips of green cloth around their heads. When they caught sight of the ambulance, they opened fire and shot at us. Luckily, we were still far enough away from them, and I was able to turn around and escape from the deadly Toyota stalking the streets of Sderot.

When I was out of their range, I slowed down a little and tried to process what I had just seen — and how I had just been on the receiving edge of an entire array of weaponry.

David and I ended up staying together for the rest of that endless day. Driving down the Avenue of Death, David called the dispatch center.

“I’m driving on Route 232, and we have counted at least seventy dead people.”

“Are you sure your numbers are accurate?”

They understood why the dispatcher was skeptical. It didn’t sound like such a thing could be true. Instead of arguing with them, David opened a Zoom call and used his phone to count the bodies together with them.

While David was on Zoom with headquarters, I continued going from car to car to see if anyone was still alive. Suddenly a warning siren went off. Missiles would be falling in their general location in a matter of seconds.

I saw a shelter on the side of the road — the kind of shelter that the government put up in public areas around the south so that people would have a place to go in case of an attack. When I got to the shelter, I noticed that there were people inside. Then I realized that terrorists had thrown a grenade into the shelter, and they had all been killed.

A little later an army vehicle pulled up to a stop near us. “We have a badly injured soldier that needs to get to the hospital,” the driver said.

Moments later the wounded soldier was in the back of our ambulance, and I was giving him first aid. The soldier had been shot in the head — there was an open wound and I could see into his skull — and needed an emergency operation as soon as possible. I did what I could, but we weren’t equipped for such an emergency. This soldier needed an intensive care ambulance, but dispatch told me the closest intensive care ambulance was at the entrance to Magen David Adom in Sderot.

By then we knew what was happening in Sderot. We knew about the shootings and the terrorists. But there was a soldier lying on the stretcher in my ambulance, and I didn’t want him to die. So David and I decided that we were going to take him to MDA station, come what may. Meanwhile, I was using something called an “ambubag,” a handheld device used to help patients breathe when there is no access to a ventilator or other source of oxygen.

When we reached the entrance to the MDA station, the soldier was still breathing. He was still with us. I felt like he was talking to me with his eyes. He was staring at me, and it was clear that he was trying to communicate something to me. An intensive care Hatzalah ambulance was waiting right where we had told it would be, and we transferred the patient while a paramedic immediately began intubating him. Moments later they sped away, while we spent a few minutes cleaning up the ambulance before turning around and driving back to Cheletz to do it all over again.

SOMETHING SWEET

CARYN GALE AND SERGIO GARELNIK are a married couple from Modiin in Central Israel. The two of them are also volunteers for United Hatzalah. When they received a message on Yom Tov from their branch head, Itzik Kara, instructing them to be on high alert, they were ready

When davening started, Caryn Gale told her husband to go to shul. “If a call comes in, I’ll come with the car and pick you up.”

“Don’t you have to say Yizkor?” he asked her.

But Caryn Gale just asked him to take the vegetable platter she’d prepared for the kiddush to shul and said she would be in touch depending on the situation.

In the middle of Shacharis, Sergio felt his phone start to vibrate. It was from a paramedic who said that he was looking for an ALS (advanced life support) qualified driver to go down south. He also needed two EMTs.

“We had no clue what we were getting ourselves into,” Caryn Gale says. “If I had known what was going on down south… well, I don’t know what I would have done.”

But they didn’t know, and off they went.

Caryn Gale thought they’d be heading over to Ashkelon or Kiryat Gat to help pull people out of a building that was hit by a rocket. The truth about what awaited them was beyond imagination, beyond anything that anyone could ever conceive.

“I had been dressed for Yom Tov,” Caryn Gale recalls, “and I changed into something more practical for the day that lay ahead. Later I was very happy that I had chosen to wear black.

“I found a bag of lollipops in the pantry and threw a huge handful of them into my bag, along with two bottles of water. I wasn’t even sure why I took them. I had this vague thought that maybe I’d need some energy later on and the sugar would help.

“As soon as we arrived at Cheletz,” Sergio says, “we were told to follow another ambulance in the direction of Sderot. Soon we were met by a team of Yamam officers, who told us to follow them. The officers had a machine gun welded to the top of their vehicle, but the reality still hadn’t registered.”

That was about to change.

AS

they entered Sderot, they saw dead bodies lying on the side of the road.

“It was so bad,” Sergio says, “that at some places I had to drive over the median in the middle of the road and drive down the wrong direction because there was a car with people who had been shot inside blocking traffic.”

They followed the Yamam officers through the streets of the city and over to the police station, parking their vehicle near where a group of Hatzolah volunteers had gathered, all still dressed in their Yom Tov clothing — white shirts and dark pants visible under their flak jackets. A few minutes later, a barrage of missiles started flying in their direction and everyone stuffed themselves into one of the public shelters on the road. When they emerged, no one really knew what was going on or what to do next.

It didn’t take long. “We met a vehicle that had a patient for us in critical condition. The ambulance was driving so fast that we couldn’t even sit on the seats,” Caryn Gale says. “I sat on the floor at the head of the patient. My job was to set up the oxygen for him — two bullets had struck him in the head, and it was very difficult to place the oxygen mask on his head because of all the bleeding. Meanwhile, Itzik and Naomi Galeono, another volunteer who’d joined us, were setting up IV lines and trying to get some drugs into his system. Sergio was trying to get to the hospital as fast as he could, zigzagging from one side of the road to the other. Between all the torched cars and scattered bodies, it was literally an obstacle course. We were being tossed all over the place, but we persisted and tried our best to keep him stable.”

At the hospital, the trauma team was waiting outside. After transferring him, the crew washed down the ambulance and headed back into the war zone to save another life.

Their next transport was 21-year-old soldier with multiple injuries, including a bullet wound in his shoulder and shrapnel in the back of his head. He was still conscious and kept on repeating, “Put me to sleep, put me to sleep, it hurts so bad, put me to sleep….”

The soldier had been injured at 8:30 in the morning, and the ambulance had only gotten to him at 12:45; he had been bleeding extensively for many hours, and his blood pressure was dangerously low. He was in such bad shape that Caryn Gale didn’t see how he could possibly survive.

Caryn Gale tried to bandage his wounds and stop the bleeding. At the same time, she needed to get an oxygen mask on his face. They were also trying to find a vein to insert an IV into his arm — and all this while Sergio was driving like a maniac to the hospital.

BYthe time their ambulance arrived at Kfar Aza, busloads of soldiers were pulling up outside the kibbutz, much of which was smoldering from the homes that had been set on fire with hundreds of victims burnt alive inside or slaughtered on the grounds. They could see soldiers lying on the ground around the perimeter, their guns up and at the ready their body language focused and alert. The surrounding fields were still filled with terrorists, and the soldiers were ready for anything.

Suddenly, an army jeep emerged carrying two families, each with two young children. They had no shoes on their feet, no purses, no phones, and the jeep that had driven them out of the kibbutz had clearly been occupied by someone who had been mortally wounded, because there was blood all over their bodies and clothing.

“When I saw the three-year-old boy covered in blood,” says Caryn Gale, “we rushed over to make sure that he wasn’t wounded, and we asked them if any of them had been hurt. They confirmed that the blood wasn’t theirs.

“Both families were transferred into an ambulance for their protection, and a thought suddenly flashed through my mind: I have lollipops in my bag!

“I went to my bag, took out the lollipops and put them in my pocket — and right then a red alert siren went off.”

Immediately the two families, along with the ambulance crew, threw themselves on the ground, the parents lying on top of their children. The three-year-old boy started crying — and Caryn Gale reached into her pocket and pulled out a lollipop.

“I have a lot of grandchildren,” she says, “and when you offer a lollipop to a child, his eyes light up. It doesn’t matter that we were surrounded by smoke and carnage and that there were sirens wailing.

“I moved over to the other two kids and handed them lollipops as well — and gave a few extra to the parents, because it was clear this wasn’t going to be over anytime soon. I had helped save many lives that day, but when I handed those lollipops to the children, it felt just as meaningful as when I had been able to stop the bleeding of wounded soldiers in my ambulance.”

After the sirens had quieted, Caryn Gale noticed a disheveled young man sitting on the sidewalk and went to sit down beside him. He told her that he had been at the music festival near Re’im, which had been raided by Hamas terrorists that morning.

“I’ve been hiding in the orchards all day,” told her. “I crawled from place to place on my stomach, hoping that I wouldn’t be caught by a terrorist. When I saw your ambulances, I knew that you were Jewish and that I would be safe if I came out.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 996)

Oops! We could not locate your form.