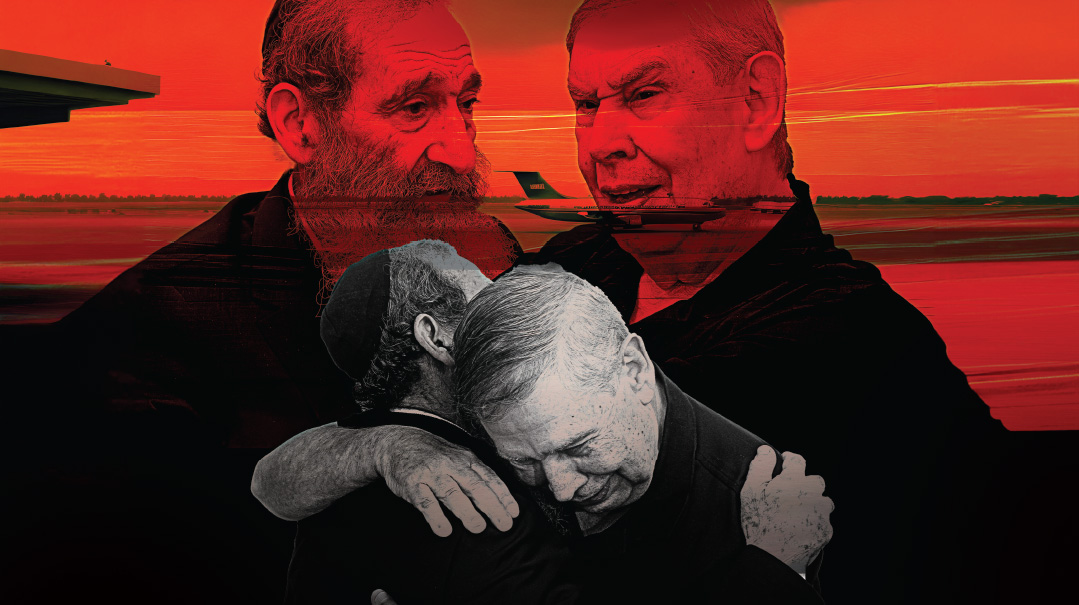

A Hier Calling

Born diplomat Rabbi Marvin Hier advocates for his people

Photos: Elchanan Kotler, BH STUDIO

Only a born diplomat could segue from a childhood on the crowded Lower East Side to a rabbinic post in remote Vancouver to earning the respect and confidence of presidents, kings, and world leaders as an acknowledged champion of human rights. After 46 years as the dean of Los Angeles’s Simon Wiesenthal Center, Rabbi Marvin (Moshe Chaim) Hier is stepping down from the post – but his “retirement” is merely a stepping stone toward his newest venture to foster peace and tolerance in Jerusalem

Dateline

Amman, Jordan. Late September 1997.

T

wo Mossad agents track down Khaled Mashal, a leading Hamas operative linked to numerous terror attacks against Israelis, as he is exiting his private vehicle.

The agents botch the operation, spraying Mashal with poison that injures him, but fails to kill him. Jordan’s King Hussein, who signed a peace treaty with Israel three years earlier, is incensed that Israel staged the attack in his country, and threatens to execute the Mossad agents unless Israel delivers an antidote to cure Mashal, being kept alive on a respirator in an Amman hospital.

Prime Minister Netanyahu complies with Hussein’s demand, and Mashal is cured, but the incident creates friction between Israel and Jordan, threatening their fragile peace treaty.

One month later, and 12,000 miles away, Rabbi Marvin (Moshe Chaim) Hier is driving to a dentist’s appointment when he receives an incoming call from General Ali Shukri, head of Hussein’s private office. Rabbi Hier led two missions from the Simon Wiesenthal Center over the years to meet with King Hussein at his palace, and Shukri knows he has a trusted voice on the other end of the line.

Shukri puts King Hussein on the line, and the king tells Rabbi Hier that his relationship with Netanyahu has deteriorated. The king knows that Bibi is on his way to the US to address Jewish groups, and that the Wiesenthal Center is on his itinerary. Hussein asks Rabbi Hier if he could facilitate a phone conversation between him and Netanyahu when he arrives in Los Angeles.

Rabbi Hier is surprised that Hussein has called him rather than going through official diplomatic channels, but he immediately contacts Netanyahu’s office. Rabbi Hier arranges for a secure phone line in a private boardroom, and the minute Netanyahu arrives at the Wiesenthal Center, he excuses himself and says he needs a few minutes to freshen up. Netanyahu and Hussein speak for ten minutes and agree to meet at Hussein’s London residence to repair their frayed relations.

For Rabbi Hier, that was all in a day’s work, but days like that one 26 years ago have added up to a lifetime of service to the Jewish People during a 60-year career as a rabbi and advocate.

As founder and dean of the Simon Wiesenthal Center (SWC), named after the world-famous Austrian Nazi hunter, Rabbi Hier met regularly with world leaders to confront anti-Semitism and hate, to support and defend Israel, and to teach the lessons of the Holocaust that apply to this very day.

Rabbi Hier has kept up the connection he made with Jordan’s King Hussein through his son and successor, King Abdullah II

R

abbi Hier is not a trained diplomat. He’s a born diplomat.

“I learned to be a diplomat growing up on the Lower East Side,” he tells me.

His wife of 61 years, Malkie, who also grew up in the same neighborhood, and has worked alongside him every step of the way, has her own take. “He was always upbeat and outgoing, but he is also humble and honest about who he is, whether he is dealing with people who are frum or not frum. What you see is what you get.”

Rabbi Meyer May, the executive director of the Simon Wiesenthal Center and a prolific fundraiser, as well as Rabbi Hier’s right-hand man for 45 years, has traveled with Rabbi Hier all over the world.

“He’s not only a visionary, but he has depth, content, and humor, and a sound business model,” Rabbi May says. “He knows how to respect high-level balabatim and knows how to manage a relationship without ever putting anyone on the spot.”

Rabbi May also shares one telling story about Rabbi Hier’s devotion to his wife, in which he put family before duty.

They were attending the 1980 Democratic National Convention at Madison Square Garden in New York and were trying to acquire four passes to reach the convention floor, where all the action takes place and the VIPs meet and greet.

Having covered nominating conventions, I can testify to the fact that floor passes are prized and also hard to come by. They only got three, and since that was one short, Rebbetzin Hier said she wasn’t the one who needed to be on the floor, so she would relinquish her spot.

“So, I’m looking around for Rabbi Hier, to let him know,” Rabbi May says, “and I can’t find him.

“These are the days before cellular phones, so I couldn’t call him. I finally ran into him on the floor. When I asked what took him so long, he said, ‘I had to make sure that Malkie had a good seat, so I’ve spent the last hour and a half making sure she was happy.’

“This is one of the best marriages I’ve ever seen,” Rabbi May adds. “He couldn’t bring himself to go to the floor until he knew with total certainty and saw with his own eyes that his wife was properly situated.”

The Simon Wiesenthal Center in Los Angeles has provided Rabbi Hier with the name recognition to reach world leaders in his fight against anti-Semitism and anti-Israel bias

H

aving met Rabbi Hier on a handful of occasions over the years, I’ve also seen his knack for putting people at ease. After five decades in Los Angeles, he retains a tinge of his accent from the Lower East Side, and much of its style and manner. Unpretentious and relaxed, he is also what journalists consider “good copy” for his willingness to share openly his experiences and his opinions of world leaders.

Rabbi Hier was born in March 1939, just six months before World War II began. His father, Yankel, immigrated to America in 1921 from Czechoslovakia, and his mother, Raisel, arrived from Europe in the mid-1930s.

Life began in a cramped apartment in Manhattan’s Lower East Side, a neighborhood that was teeming with European Jewish immigrants. Rabbi Hier attended elementary school at the Rabbi Shlomo Kluger Yeshiva on Houston Street.

His father, a lamp polisher, was so good at his craft that his foreman expected him to work on Shabbos and Yom Tov. Needless to say, job turnover was frequent and money was scarce, but his dedication to Yiddishkeit was fervent.

“My father didn’t like the idea that he couldn’t afford to pay shul dues, so he would make up for it by setting up the kiddush on Shabbos and helping organize the sale of High Holiday seats,” Rabbi Hier recalls.

After World War II, many Holocaust survivors moved to the neighborhood, and the traumatic event weighed heavily on everyone’s minds. The first time Rabbi Hier began to understand what had happened was the year he had to spend a longer-than-usual time outside shul during Yizkor. Afterward, he asked his father why it had taken so much longer that year.

His father answered: “Moishe, many of our friends are saying Yizkor for their parents and for others who were killed by the Nazis.”

When Moishe asked if Yizkor took that long in Zeide’s shul too, his father replied sadly: “I’m afraid it’s the same in every shul.”

When Young Moishe took bar mitzvah lessons from Rabbi Yankele Flantzgraben, a senior rebbi at his yeshivah and a Satmar chassid. “Say it louder,” Reb Yankele would tell young Moshe Chaim. “Say it loud for those Jewish children who never had a bar mitzvah because the Nazis killed them.”

Rabbi Hier remembers feeling troubled. Having seen movies where the good guys always rounded up the outlaws and came out on top, he wanted to know where all the good guys were when it came to saving the Jews. He had questions and no good answers.

He found his satisfaction behind a shtender, learning for six years at the Rabbi Jacob Joseph (RJJ) beis medrash, where he earned semichah and also took his first stab at being an entrepreneur.

Once, before Succos, he and two bochurim hiked along the Saw Mill River Parkway along the Hudson River just north of New York City, where many aravos trees grew along the banks. Most of them were bug-eaten, but Rabbi Hier cut a couple of samples and brought them to the Bronx Botanical Gardens, where an expert told him the plant was called a Salix purpurea and grew in two places: Phoenix, Arizona, and Princeton, New Jersey.

Rabbi Hier called the nursery in Princeton and asked if they could grow some trees for him. They agreed, but on condition that the volume would be high enough to make it profitable for them. Rabbi Hier said, “No problem, I can buy as many as you can grow.”

In the first season, he bought 10,000 aravos at four cents each. He took them to the Satmar Rebbe’s gabbai, who was so impressed with the quality that he bought the whole stock.

In future years, Rabbi Hier was able to sell between 60,000 to 80,000 aravos to a variety of chassidic courts.

“And with that,” Rabbi Hier said, “I had enough money that when I met my wife, I could buy her an engagement ring and we could get married. Without that, I wouldn’t have had a dime.”

The Wiesenthal Center’s Moriah Films Division has produced 17 holocaust documentaries and won two Academy Awards

T

he money he earned might have been enough to pay for a ring and a few dates, but Rabbi Hier was going to need a real job to support a family.

Shortly before Rabbi Hier’s wedding, Rabbi Bernard Goldenberg, the senior rabbi at Congregation Schara Tzedeck in Vancouver, visited RJJ seeking a qualified candidate for an assistant rabbi.

Rabbi Shmuel Dovid Warshavchik, a rebbi in RJJ, recommended Rabbi Hier, who was still a few months short of earning semichah.

Rabbi Goldenberger was impressed and hired Rabbi Hier on the spot. He explained that the synagogue was Orthodox and most of the members were not, so it would be a good opportunity to teach. He also said he planned to move back to New York in a couple of years, and Rabbi Hier would be in line to take over at Schara Tzedeck.

Rabbi Hier’s wife-to-be Malkie agreed it was well worth the risk of moving 3,000 miles west to a place they hadn’t heard of. “A lot of his friends who got semichah were becoming English teachers,” she said. “There weren’t too many opportunities, so we said, let’s go there for a year, it’ll be an experience.”

As is often the case, one year turned into 15, once they got over the culture shock.

“At first, we were shocked that some people drove to the shul on Shabbos,” Rebbetzin Hier said. “It wasn’t easy, but we learned how to deal with non-frum people and with time, some of them and many of their kids became frum.”

Schara Tzedeck was also a wealthy and charitable congregation, and Rabbi Hier convinced the board to invest in their youth. He established an NCSY branch and created other programs to attract young people to services and shul activities. That’s how Rabbi Hier got to know Rabbi Abraham Cooper, who eventually became the SWC’s associate dean and director of global social action.

At the time, Rabbi Cooper had never been west of Chicago, but when NCSY asked him to help coordinate a shabbaton in Seattle, he spent a Shabbos with the Hiers to recruit youths from Vancouver.

“Rabbi Hier has a great sense of humor, but more than that, he knew what he wanted to accomplish, and he pursued it,” Rabbi Cooper says, who adds that he met his future wife the same week, on that West Coast swing.

As a member of the clergy, Rabbi Hier began to get his feet wet as a spokesman for Jewish affairs. He became active in the struggle for Soviet Jewry, arranging a demonstration at the Vancouver Hotel when Soviet premier Alexei Kosygin visited.

Rabbi Hier also attended a formal dinner that Queen Elizabeth and Prince Philip hosted. When the prince spotted his kippah, he engaged Rabbi Hier in a brief conversation about the local Jewish community.

Rebbetzin Hier also took advantage of the opportunities Vancouver had to offer, earning a BA from Simon Fraser University and a master’s degree in urban planning and statistical analysis from the University of British Columbia.

After the Hiers were blessed with two sons, Ari and Avi, who needed better chinuch opportunities, they realized it was time to move on. They spent three months in Eretz Yisrael to ponder their future, and before they left, Rebbetzin Hier got an inspiration. She recommended that her husband to take the boys to the Gerrer Rebbe, Rav Yisrael Alter, widely known as the Beis Yisrael, for a brachah and also ask him for career guidance. It was only fitting because the Rebbe had rebuilt Gur into one of the world’s largest chassidic courts after the Nazis almost annihilated them in Europe. The Rebbe blessed the boys, and told Rabbi Hier, in Yiddish: “Go immediately, you will have great success.”

The only problem was, they didn’t have concrete plans. Rabbi Hier had this idea to start a yeshivah in Los Angeles, and he confided his plan to Sam Belzberg, a member of his kehillah, who, along with his brothers Hyman and William, had become successful in Vancouver’s banking and real estate sectors.

Their initial conversation took place four days after the Beis Yisrael said to go immediately. Sam Belzberg wasn’t as certain. Rabbi Hier recounts that Sam first told him, “Rabbi, you shouldn’t leave. As a businessman, I can tell you that you have a good position here.”

Then he thought again, and said, “Rabbi, mull it over for a month, and if you still feel strongly about it, come back and see me.”

Rabbi Hier tells Mishpacha’s Binyamin Rose his goals for Jerusalem’s new Museum of Tolerance include fostering relations between Israel and peaceful Arab neighbors, and to tone down, and even eliminate extremism in Eretz Yisrael

A

month later, Rabbi Hier sought out Sam Belzberg and shared his plan to develop a yeshivah for post-high-school students, focusing on those who didn’t have an Orthodox background. Sam and his brothers pledged $500,000 to buy a building that eventually became home to the Yeshiva University of Los Angeles. Established in 1977, to date YULA has graduated well over 2,000 young men and women.

Rabbi Hier served as the dean at YULA until 2005. One of his students, Brian Dror, who now also serves on the Wiesenthal Center audit committee, remembers Rabbi Hier fondly.

“He was very kind and approachable, and while he had a great sense of humor, he also toed the line,” Dror says. “You could have fun but you couldn’t cross his lines.”

Always on the lookout for new opportunities, Rabbi Hier first got the idea of starting a Holocaust educational center after visiting the La Brea Tar Pits in Los Angeles. A girl on the same tour asked the tour guide if dinosaurs would ever return to the earth, and she replied no, due to climate change.

Rabbi Hier began pondering this strange question and wondering why people were concerned about the extinction of dinosaurs and not about more recent cataclysmic events such as the Holocaust. To make matters more urgent, anti-Semitic and anti-Israel sentiments were on the rise. A 1977 Supreme Court decision opened the door to allowing neo-Nazis to march in Skokie, a Chicago suburb with a large Jewish population. France had just released Abu Daoud, the mastermind of the 1972 Munich Olympics massacre of 11 Israelis.

Rabbi Hier originally thought of establishing a Holocaust education center at YULA, but at the time, this was a novel idea in America, and he knew he needed a big name to back it.

He set his sights on Simon Wiesenthal, a Polish Jew who lost 89 relatives in the Holocaust and who barely survived his own concentration camp incarceration. Wiesenthal was head of the Jewish Documentation Center in Vienna and gathered copious evidence to help bring the war criminals to justice.

Rabbi Hier called Wiesenthal, reminding him that he and Rebbetzin Hier had met him eleven years prior in Vienna after a visit to the Mauthausen concentration camp. Rabbi Hier told Simon he needed his help with an important project and wanted to come to Vienna to meet him.

Wiesenthal agreed. Rabbi Hier took Roland Arnall with him. Arnall was also a Holocaust survivor who eventually became the US ambassador to the Netherlands.

Wiesenthal was intrigued but noncommittal at that first meeting. However, he sent his lawyer Marty Rosen to meet with Rabbi Hier in Los Angeles, and thanks to Rosen’s endorsement, Wiesenthal agreed.

The Simon Wiesenthal Center opened on November 22, 1977, in 4,000 square feet of space in the west wing of YULA.

It was an instant success. The Center’s educational arm, the Museum of Tolerance, has hosted more than 7.5 million people since it opened in 1993. The Center has produced some 17 documentaries, two of which — Genocide and The Long Way Home — have won Academy Awards.

Rebbetzin Hier also deserves credit for the Wiesenthal Center turning into a global human rights organization. She applied what she learned in statistical analysis to create a direct-mail campaign modeled after the Democratic National Committee that brought in some 400,000 new members and donors. As an accredited NGO recognized by major world bodies, including the UN and the Council of Europe, it has provided Rabbi Hier with access to world leaders to confront anti-Semitism, hate, anti-Israel bias, security of Jews worldwide, and to impart the lessons of the Holocaust for future generations.

Partially due to its film division, the Wiesenthal Center has attracted donors and members from the entertainment industry. Perhaps the one entertainer with the biggest impact was singer Frank Sinatra.

Rabbi Hier enjoys relating the famous story, first told at a 2008 Washington fundraising dinner for the Yitzhak Rabin Center, of how Teddy Kollek visited New York before the 1948 War of Independence to help smuggle arms to Israel’s underground. The FBI was trailing Kollek, who had collected $1.1 million in cash to bribe the captain of a ship docked along the East River to take the arms across the ocean to Israel.

Kollek’s makeshift office was in the same building where Sinatra was performing. Rabbi Hier said that Sinatra once told him that aside from feeling a sense of devastation over the Holocaust, he was favorably disposed to the Jewish People because of a Jewish neighbor who was kind to him when he was growing up in a family of poor Italian immigrants in Hoboken, New Jersey. He agreed to take the money to the ship’s captain.

When Kollek left his office with an empty satchel, with the FBI agents in pursuit, Sinatra left through another exit with a paper bag containing the money and paid the captain.

When I asked Rabbi Hier if he has faced criticism for the links and friendships he formed in the entertainment community, he didn’t mince words.

“They do, and people criticize all the time,” Rabbi Hier said, but he said he learned from Simon Wiesenthal the importance of building broad-based support for efforts that can aid the Jewish People and keep them out of harm’s way.

“Simon once told me, ‘Why did I lose 89 members of my family in the Holocaust? Because we didn’t have any chaveirim. We didn’t have any friends or support from non-Jews. We didn’t have anybody we could call on or count on in times of emergency. We thought we could save ourselves by ourselves, and that was a big mistake.’

“I take the same position that Simon Wiesenthal did,” Rabbi Hier says. “It’s incumbent upon us to not just be friends with people who wear arba kanfos. We need friends we can reach in the broader community at times of emergency as well.”

There is a postscript to the Sinatra episode. Because he supported Jewish causes, the Arab League’s boycott bureau in Cairo leveled a ban in 1962 against Sinatra’s recordings and films.

As it turns out, one of Sinatra’s biggest fans is King Hamad al-Khalifa of Bahrain. When he wanted to obtain some Sinatra recordings and discovered he couldn’t buy them in Arab countries, he was livid. But kings have their methods, and he found a way to obtain them directly from the recording company.

In 2017, Rabbi Hier led a delegation to Bahrain, where the king denounced the Arab boycott on Israel and declared that all visitors to Bahrain would enjoy freedom of worship. Three years later, Bahrain signed onto the Abraham Accords, normalizing relations with Israel.

Simon Wiesenthal (l) and Frank Sinatra (c) share a laugh with Rabbi Hier, renowned for his sense of humor

V

ery early on, the Wiesenthal Center found that it would encounter its most difficult challenges when dealing with the international community.

In 1979, Germany’s 20-year statute of limitations on prosecuting Nazi war criminals was about to expire. The West German government in Bonn had extended it twice, but this time, the political opposition was strong.

After consulting with Simon Wiesenthal, Rabbi Hier and Rabbi Cooper organized a 30-member delegation, including congressmen, Holocaust survivors, civil rights activists, and academicians to meet with Chancellor Helmut Schmidt.

Rabbi Hier contended that it would be unacceptable to murder millions of people, be considered criminals for 20 years, and then be exonerated because they were clever enough to evade justice.

Schmidt parried, saying he respected Rabbi Hier’s view, and that no country did more than West Germany to prosecute former Nazis, but Holocaust guilt was weighing heavily on the younger generation, who resented being blamed for the sins of their fathers and grandfathers.

The delegation held their breath as the German parliament, the Bundestag voted.

The news was good. The vote was 255-222 to extend the statute of limitations indefinitely.

In its July 4 article reporting on the vote, the Washington Post attributed it to the screening in Germany of the television series Holocaust and the dramatic visit a month earlier by Pope John Paul II to Auschwitz.

Rabbi Cooper agrees with that assessment but he said their meeting was pivotal.

“Schmidt did one important thing,” Rabbi Cooper said. “He announced that there wouldn’t be party discipline for the vote so that the members of the Bundestag could vote their conscience.”

Four years later, Rabbi Hier also arranged a delegation to meet with Pope John Paul II, following a Wiesenthal Center mission to mark the 40th anniversary of the Warsaw Ghetto uprising.

While Rabbi Hier strongly believes in reaching out to men and women of all races, colors, and religions, he would never compromise his religious standards, as is illustrated by the following story.

The delegation was seeking a private audience with the pope when they got a call from Monsignor Jorge Mejia, secretary of the Vatican’s commission for religious relations with Judaism. Mejia confirmed the meeting would take place in the Vatican, on Saturday at 11 a.m.

“I was standing right next to Rabbi Hier when the call came in,” Rabbi Cooper says. “Nobody else was in the room, and Rabbi Hier said exactly this: ‘How about 11 a.m. Sunday?’” (That time would have conflicted with the pope’s Sunday sermon.)

“So, Rabbi Hier comes into the next room and announces to the group that he just canceled the meeting with the pope because it conflicted with Shabbos,” Rabbi Cooper says.

Most of the delegation consisted of nonobservant Jews who were deeply disappointed at the scheduling difficulties.

As quickly as the atmosphere got deflated, it soon got reinflated. Since the following Monday was a national holiday in Italy, Monsignor Mejia called Rabbi Hier back and said because the pope’s holiday schedule was light, he could meet with the contingent on Monday at 11 a.m.

Before the call ended, Monsignor Mejia added: “I want everyone here to know that we in the Vatican, when we learned of Rabbi Hier’s response, knew we were dealing with someone who reflected the true values of Judaism.”

Growing from a lad to a chassan in Manhattan’s Lower East Side

R

abbi Hier also doesn’t back down when it comes to dealing with presidents.

In 1984, when Ronald Reagan was president, Rabbi Hier utilized the Freedom of Information Act to obtain a formerly classified document that showed that the US Counterintelligence Corps had briefly detained notorious war criminal Josef Mengele in Vienna but released him. Mengele was known as the “Angel of Death” for his cruelty in the medical “experiments” he performed in Auschwitz.

Rabbi Hier and Simon Wiesenthal wrote President Reagan asking for a full-fledged investigation. Reagan forwarded their letter to the Department of Defense, which refused to release any further documents.

Rabbi Hier called news conferences in New York, Toronto, and Los Angeles and discussed the case on the weekly Sunday morning news program This Week with David Brinkley.

A week later, Pennsylvania senator Arlen Specter launched a Senate Judiciary Subcommittee hearing and New York senator Alphonse D’Amato joined a Wiesenthal Center lawsuit to force the government to declassify the other documents relating to the case.

A few months later, as a result of the publicity, Brazilian authorities revealed that Mengele had suffered a stroke and drowned in 1979.

Before Reagan became president, Rabbi Hier had met Jimmy Carter at a White House ceremony where he presented Simon Wiesenthal with the Congressional Gold Medal.

Sixteen years after being voted out of office in 1980, Carter published a book, Palestine: Peace not Apartheid, accusing Israel of being an apartheid state and distorting the Israel-Palestinian conflict.

Outraged, Rabbi Hier used the Wiesenthal Center’s reach, whose members sent 15,000 letters of protest to Carter’s Atlanta office.

Carter sent Rabbi Hier a curt response in a handwritten note that said: “To Rabbi Marvin Hier. I don’t believe that Simon Wiesenthal would have resorted to falsehood and slander to raise funds. Sincerely, Jimmy Carter.”

Rabbi Hier fired back, saying while he doesn’t consider Israel infallible or incapable of errors in judgment, Israel practices self-defense and not apartheid.

Unfortunately, Carter’s apartheid label sticks to Israel to this day.

Rabbi Hier also challenged President Obama in a June 2015 White House meeting, when Obama tried to sweet-talk Rabbi Hier and leaders of 13 other Jewish organizations into supporting his Iran nuclear deal.

Obama contended that Iranian leaders knew their economy was sinking and would be willing to compromise.

Rabbi Hier wasn’t buying it and still doesn’t.

He cites a four-page typewritten letter signed by Hitler in 1919 that the Wiesenthal Center obtained in 2011 after Hitler’s signature was verified by a historian, which made it abundantly clear that Hitler’s goal was to annihilate the Jews.

“From that, we should learn that we can’t deal with Iran,” Rabbi Hier says. “But a lot of people in Washington still don’t get that idea. They don’t understand that you’re dealing with the new Nazis, and you can’t trust anything they say. We should never make that mistake again. When somebody gets up in the world, anywhere, and says we have to get rid of the State of Israel, we’ve got to go after that person and watch them 24/7, 365 days a year.”

That includes professional athletes who have large fan bases.

Last November, when Brooklyn Nets basketball star Kyrie Irving peddled anti-Semitic propaganda to his 4.6 million followers on Twitter, the Wiesenthal Center leaped into action.

“We were all outraged and angry,” says Brian Dror, “but Rabbi Hier put us all at ease when he explained how he was going to handle it.”

Rabbi Hier’s strategy was to deal through the National Basketball Players Association and reach out to the NBA commissioner, instead of going on the attack.

“Rabbi Hier urged education through tolerance rather than hitting someone over the head with a baseball bat,” Dror says.

Irving ended up apologizing and pledged a $500,000 donation toward causes and organizations that work to eradicate hate and intolerance.

At the end of December, Rabbi Hier will officially retire as the dean of the Simon Wiesenthal Center in Los Angeles. The board is actively recruiting his replacement, although Rabbi Hier will remain active, splitting his time between Los Angeles, training his successor, and his newest project, the sprawling new Museum of Tolerance in the center of Jerusalem that is scheduled to open in 2024.

Rabbi Hier gave me a tour of the new facility on an early summer visit and made sure to show me the entryway, which has many plaques dedicated to gedolei Torah throughout the generations.

It’s all part of who Rabbi Hier is. A reverence for the Torah and mesorah, with the recognition that each generation has its challenges and must relate to the politicians and influential people of the times.

When he arrives in Jerusalem, his goals include continuing to foster relations between Israel and the Arab neighbors that want to make peace, and to tone down and even eliminate extremism in Eretz Yisrael.

It’s a tall order, but Rabbi Hier feels he is up for the challenge.

“As religious Jews, we have to be able to say, ‘I believe in Hashem and am very proud to be an Orthodox Jew and to walk in the derech of my parents, my grandparents’ — but at the same time, to also be respectful of people who are not quite on the same derech.

“I do this by reacting with kindness, with understanding. We don’t want a civil war in Israel. It’s too small of a country. If we have a civil war, we will not have Eretz Yisrael.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 980)

Oops! We could not locate your form.