A Glimpse of Divinity

Sometimes it takes a trip to the heavens to appreciate G-d’s handiwork on Earth. That’s what the Apollo 11 crew — the first men to step on the Moon — realized 50 years ago

F

ifty years ago, on July 21, 1969, Buzz Aldrin became one of the first two men to land on the moon as part of the Apollo 11 space mission. Participating in such a historic event gave him pause, and he wanted to find a suitable way to mark the occasion. Aldrin, a religious man, was aware “that G-d reveals Himself in the common elements of everyday life.” He wanted to pay homage to the fact that “G-d was revealing Himself on the moon, too, as man reached out into the universe” by invoking G-d’s name in an explicitly religious observance. But as governments, the media, and entire nations were swept up in the dramatic scenes of silver- clad men blasting through the atmosphere, the religious subtext became a source of controversy.

NASA (the National Aeronautics and Space Administration) was still smarting from a recently concluded legal battle with an atheist who challenged public displays of religiosity. The higher-ups wanted to avoid ruffling anybody’s feathers, and instructed Aldrin to keep his ceremony low-key.

So instead of making a public reminder of the thanks due to G-d, Aldrin radioed to NASA: “I would like to request a few moments of silence… and to invite each person listening in, wherever and whomever they may be, to pause for a moment and contemplate the events of the past few hours, and to give thanks in his or her own way.”

Many astronauts, both before and after Aldrin, have been moved to publicly acknowledge G-d’s power and give thanks for His gifts to mankind. Less than seven months before Aldrin’s moonwalk, the Apollo 8 mission had orbited the moon for the first time in history. The crew members were the first humans to see the dark side of the moon, and the first to see the Earth as a whole planet. They captured the beauty of the sight in their famous photo of Earthrise — planet Earth floating alone in the eternal night of space, warmly welcoming and achingly vulnerable. The magnificent sight led them to transmit a unique broadcast from their spaceship, which garnered the largest television audience ever at that time. One billion people, a quarter of the Earth’s population, tuned in to hear the astronauts take turns reading aloud an English translation of the first ten verses of sefer Bereishis, describing Creation.

Jews in Space

Jews have also brought religious awareness to space. Space Shuttle astronaut Jeffrey Hoffman brought a miniature sefer Torah into space in 1996 and read aloud the pesukim about Creation (in the original, that is) as his spacecraft orbited over Jerusalem. Israeli payload specialist Ilan Ramon recited Kiddush aboard the ill-fated space shuttle Columbia. And Jewish-American astronaut Gregory Chamitoff Velcroed a rocket-shaped mezuzah to the door of his cabin in the International Space Station in 2008.

“There are only bunks for half the crew, so we share them with someone on the other shift, who can sleep while we work,” Chamitoff said at the time. He didn’t want to leave the mezuzah up for a non-Jew who didn’t know what it was. “I would put the mezuzah on my door when I went to sleep and remove it every morning.”

But on the fourth day of the mission, he said, “The guy who had been using my bunk while I worked said, ‘Hey, Jeff, the mezuzah is a nice idea!’ I slapped my forehead. It was Scott Horowitz, another Jewish astronaut. So after that, we just left the mezuzah up, Velcroed to the wall, for both of us.”

Many atheists and agnostics think science and religion must be at loggerheads. They assume that astronauts, with their training and scientific education, must be atheists and agnostics like themselves. But in fact, statistically, astronauts are more involved in organized religion than their Earth-bound contemporaries.

Even the Soviet cosmonauts, products of a vehemently atheist government, admitted to religious inclination. This happened when Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev claimed that the first man in outer space, Yuri Gargarin, had said, “I flew right through the heavenly mansions and did not run into anyone, neither the Almighty nor the angel Gabriel nor the angels of Heaven. It seems, then, that the sky is empty!”

But this was a lie. Gargarin was a faithful member of his church, and he told his friends, “An astronaut cannot be suspended in space and not have G-d in his mind and his heart.”

The Overview Effect

Imagine looking through a window and seeing the planet Earth from a distance — everything we know, our lives and the lives of everyone, contained within a small, blue orb suspended against the vast blackness of space. Would that perspective change your conception of the world, of humanity?

Many of us have seen photographs depicting this, but the actual sight is one that only a very few human beings have been privileged to view. Those lucky enough to see it, whether or not they hold religious outlooks, have been profoundly affected by the experience.

Astronauts are known to have been moved to heightened spirituality. Seeing their home planet from space prompts them to think about whether their flights are about more than just engineering and science. Writer Frank White was intrigued hearing astronauts describe their journeys, and interviewed dozens of them for his book The Overview Effect: Space Exploration and Human Evolution. Almost all of them spoke to him of the wonder, humility, and unity they felt when viewing Earth from space — and their sense of awe. It made them realize just how finely tuned the universe is, and how perfectly balanced.

This led them inevitably to the realization that there’s a Creator. Gene Cernan, the last man to stand on the moon, remembered looking back on the blue Earth and thinking, “Too much logic. Too much purpose. Too beautiful to have happened by accident.”

Astronaut James Irwin remarked that seeing Earth this way showed him “how intricately G-d cares for us.”

This phenomenon is so pronounced that Frank White gave it a name, the “Overview Effect” which he also used as the title for his book. It’s the intense reaction triggered by seeing Earth from space. The vision so jars a person’s perspective that it forces his “self-schema” to an entirely new point of view. Every educated person knows Earth is a lonely speck floating in space, a dot of blue amid so much black. But seeing it with one’s own eyes is a life-altering experience.

Scientist Sam Durrance, who flew on two NASA Space Shuttle missions as a payload specialist, described the feeling: “You’ve seen pictures and you’ve heard people talk about it. But nothing can prepare you for what it actually looks like. The Earth is dramatically beautiful when you see it from orbit, more beautiful than any picture you’ve ever seen. It’s an emotional experience because you’re removed from the Earth but at the same time you feel this incredible connection to the Earth like nothing I’d ever felt before.”

Pale Blue Dot

In space, a single gloved thumb held at arms-length can block the view of everything and everyone the astronaut has ever known. This leaves astronauts pondering the insignificance and vulnerability of mankind. This thought evolves until the space traveler gets a sense of man’s rightful place in the universe. Which explains why Buzz Aldrin recited the English translation of the eighth perek of Tehillim when he returned to Earth: “When I behold Your heavens, the work of Your fingers, the moon and the stars, which You have set in place: What is man that You are mindful of him, and the son of man that You care for him?”

Astronauts treasure this expansion of consciousness. The crew of Skylab 4 went on strike when they felt they weren’t given enough time to take in the sights of space. They turned off their radio link to Earth, so as not to be interrupted, and refused to work for 24 hours so they could contemplate the view. In the words of their flight director, they were asserting “their need to reflect, to observe, to find their place amid these baffling, fascinating, unprecedented experiences.”

An analysis of 56 astronauts’ memoirs and interviews showed that along with increased spirituality, they developed greater concern for other people. These feelings of awe and connection to humanity — the two pillars of religion — were reported by astronauts from all over the world: America, China, Germany, Syria, and Russia.

All the astronauts reported being shaken by the realization of the artificiality of “the scars of national boundaries,” as a Syrian astronaut put it.

“I really believe,” said astronaut Michael Collins, “that if the political leaders of the world could see their planet from a distance of 100,000 miles, their outlook could be fundamentally changed. That all-important border would be invisible, that noisy argument silenced. The tiny globe would continue to turn, serenely ignoring its subdivisions, presenting a unified facade that would cry out for unified understanding, for homogenous treatment. The Earth must become as it appears: blue and white, not capitalist or Communist; blue and white, not rich or poor; blue and white, not envious or envied.”

This gives such a jolting sense of universal brotherhood that the astronauts returned home with “a renewed sense of purpose” and a greater feeling of connection with humanity as a whole. It turns the entire Earth into one’s own neighborhood.

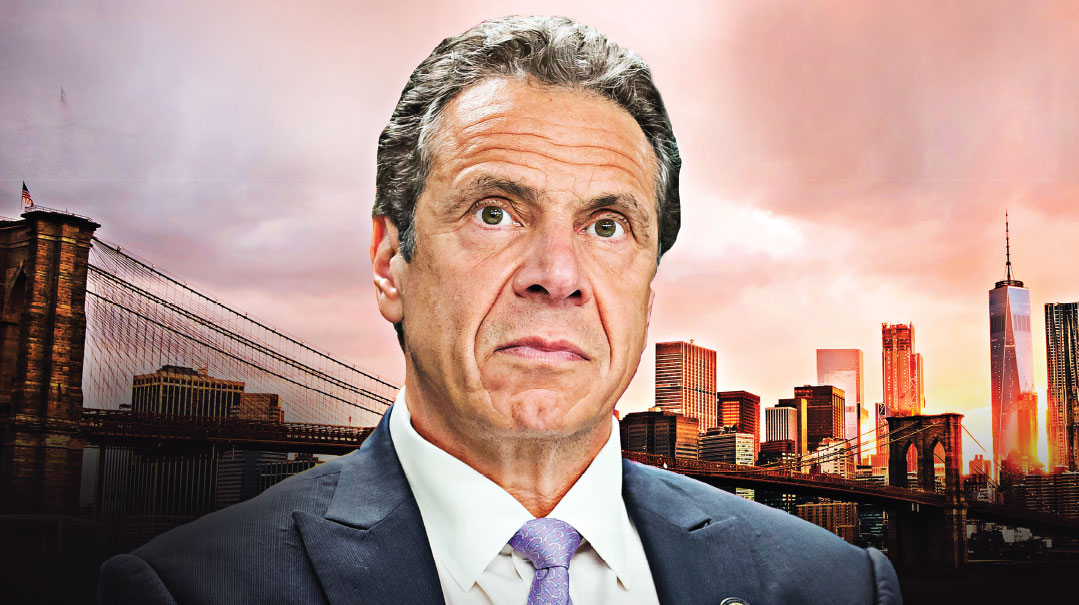

The Apollo 11 crew, Neil Armstrong, Michael Collins and Edwin (Buzz) Aldrin, 50 years ago. An astronaut can't be suspended in space and not have G-d in his heart.

The Effects of Awe

Those of us who remain earthbound can also experience awe-inducing moments — say, by contemplating a storm-swept sea, listening to an exquisite violin concerto, experiencing the birth of a child, or forging a powerful spiritual connection through prayer or meditation. These have an effect, much as the astronauts’ experiences do, although aesthetic beauty by itself does not exert the same kind of long-term changes found in more meaningful experiences.

According to a report published by the American Psychological Association, “Awe, the small self, and prosocial behavior,” those who’ve been awed by the beauty or vastness of nature have a weakened sense of self. They report feeling small and insignificant, and more connected to something larger than themselves. Focus on narrow self-interest wanes and concern for others takes its place. The sense of being the center of the world is forgotten. Even those who just recall a scene of natural beauty show this effect.

It makes people nicer, too. Awe causes people to feel a greater sense of oneness with others, and a study of over 1,500 people from across the United States showed that it makes them more generous.

Awe also makes time feel more expansive. That makes those who experience it more willing to volunteer their time to help others, and less impatient. They show a preference for experiences over material goods, and their satisfaction with life increases.

These are not just short-term blips. The more powerful the awe-inducing experience, the longer the effects last. Astronauts’ lives are changed forever by the awesomeness of their travels. The internal shake-up “settles into long-term changes in personal outlook and attitude involving the individual’s relationship to Earth and its inhabitants,” says David Yaden, co- author of the study “The Overview Effect: Awe and Self-Transcendent Experience in Space Flight.”

Back on Earth, many returning astronauts dedicated at least part of their lives to bettering the world, through politics, spiritual outreach, foundations for the mentally handicapped, and in other ways. “Seeing this [Earth] has to change a man, has to make a man appreciate the creation of G-d and the love of G-d,” said astronaut James Irwin who, once he was back on Earth, dedicated his life to spreading his newfound knowledge.

Or, as astronaut Edgar Mitchell said, “We went to the moon as technicians. We returned as humanitarians.”

Science doesn’t answer the questions that religion poses. But it brings humans to encounter their smallness in the face of the vastness, beauty, and intricacy of the universe. As Space Shuttle Mission specialist Tom Jones explained, “Perhaps the most moving experience of space travel for me was seeing the Earth set against the vast cosmos — of which our world is a tiny part. It’s awe-inspiring to think of one’s self as an insignificant human living on our small planet, set in the immensity of Creation — the universe — we’re a part of. I felt that perspective was simultaneously humbling and an intensely personal gift from G-d.”

We are awed by the genius of man, who can set foot on the moon and, soon perhaps, on another planet. We are awed by the beauty revealed by scientific exploits, because reality is awesome. When the Earth is viewed in a context only an astronaut can see, his vision leaves no room for accidents.

The scroll that reached heaven

Before dawn, four candles were lit in the barracks of Bergen-Belsen while Rav Shimon Dasberg unfurled his four-and-a-half-inch-tall sefer Torah. The windows were covered with blankets so the SS wouldn’t notice what was happening. It was the morning of Joachim Joseph’s bar mitzvah. Rav Dasberg had prepared Joseph for his bar mitzvah, secretly teaching him at night how to read from the Torah. Young Joachim said birchos haTorah and read his parshah.

“There were people listening in the bunks all around,” said Joseph. “Afterward, everyone congratulated me. Somebody fished out a piece of chocolate that he had been saving, and somebody else fished out a tiny deck of playing cards. I was very happy.”

Dasberg told Joseph, “This little sefer Torah is yours to keep now, because I’m sure that I won’t get out of here alive, and maybe you will.”

Joseph said, “You know how children are. I didn’t want to take it. But he convinced me. And the condition was, I must tell the story.

“And then everything was taken down, and we went out to morning roll call.”

Dasberg died less than two months before the British liberated the camp. But Joseph survived and grew up to become a physicist in Israel. He didn’t talk about the war for 40 years.

“I buried it deep down,” he said. “I managed to forget it.”

Israel’s only astronaut, Ilan Ramon, the son and grandson of Auschwitz survivors, went to Joseph’s home one day to discuss experiments that would be performed on the shuttle. Ramon noticed the sefer Torah, and Joseph told him its story. He readily agreed to let Ramon take it into space, so that his promise — to tell the story — would be kept.

Ilan Ramon told the story to the world on a live teleconference from the Columbia space shuttle. “It represents more than anything the ability of the Jewish People to survive. From horrible periods, black days, to reach periods of hope and belief in the future.”

The Columbia disintegrated during re-entry. Ilan Ramon was killed, and while the sefer Torah was almost certainly destroyed, 37 pages of his private diary were discovered in a Texas swamp two months later — and one of those pages had on it his handwritten Kiddush which he recited in space.

Jewish in Space

Lighting a flame is about the most dangerous thing one can do in the oxygen-rich atmosphere of a spacecraft, so the first Jewish American in space, Judith Resnick — who died in 1986 when the Space Shuttle Challenger was destroyed during a launch mission — lit electric lights to usher in Shabbos when she was in the space station.

Since astronaut David Wolf — who lived on the Mir Space Station for several months in 1997 — couldn’t light his chanukiah in space, he commemorated Chanukah by smashing world records for spinning dreidels.

“It went for about an hour and a half [because of zero-g, complete absence of gravity] until I lost it,” Wolf said. “It showed up a few weeks later in an air filter. I figure it spun for about 25,000 miles.”

Gary Reisman, the first Jewish astronaut to live on the International Space Station, wanted to bring matzos for Pesach, but was told that the crumbs would be to hard too contain in zero gravity and would endanger the machinery.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 769)

Oops! We could not locate your form.