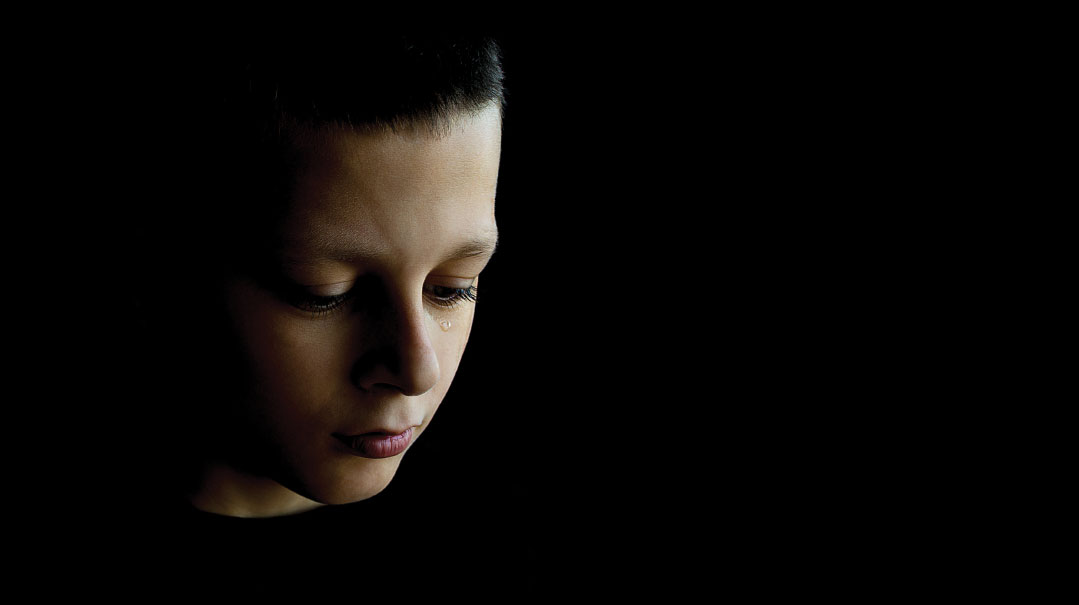

Silent Mourners

If ever there was a situation of b’makom sh’ein anashim, hishtadel lihyos ish, I thought to myself, this is it

In the close-knit chassidic community in Ramat Beit Shemesh that my family and I belong to, my ten-year-old son, Shimmy, was best friends with another boy, a lively, energetic kid whom I’ll call Yitzi.

The cheder that Shimmy and Yitzi attended was situated on our sleepy, dead-end street, and all the other boys on the block attended this cheder as well, so they all knew each other and played together. But Shimmy and Yitzi had a special bond — it was always Shimmy and Yitzi, Yitzi and Shimmy.

One Monday afternoon, the quiet of our residential street was shattered by the wailing of sirens as ambulances, police cars, and fire trucks converged in front of the building where Yitzi lived. Curious to see what was going on, Shimmy hurried out onto our porch and called down to one of his friends below on the street to find out what the commotion was about.

“Something bad happened to Yitzi,” the friend called back up to him.

Shimmy raced downstairs and down the block, where a throng of kids had already congregated and were watching as paramedics moved a limp Yitzi onto a stretcher and into an ambulance.

Later that day, we heard the horrific details of what had happened. Yitzi had been playing with a rope, which somehow became wound around his neck, choking him. He was found unconscious and rushed to the hospital, where he was pronounced in critical condition.

From the moment Yitzi was taken away by ambulance, Shimmy opened a Tehillim and did not stop davening and crying. Minyanim were convened in shuls throughout the neighborhood for people to say Tehillim, and, instead of playing, the children sat and said Tehillim as well. The next morning, when I entered Shimmy’s room to wake him, I saw that even in his dreams his lips were murmuring words of Tehillim.

While the adults in the neighborhood were whispering, “Is Yitzi going to survive?” the children were innocently asking, “When is Yitzi coming home?” They could not even conceive of the possibility that Yitzi, who was always so alive, might never come home.

The parents of Yitzi’s friends did not know what to tell their kids. Some put on a confident face and assured their children that Yitzi would soon be discharged from the hospital. Others gave vague answers regarding his prognosis.

Early Friday afternoon, the terrible news came: Yitzi had passed away.

Trained as I am as a psychotherapist, I knew I had to be the one to tell Shimmy what had happened. Still, professional training notwithstanding, informing your own young son that his best friend just died is a gruesome task.

Not wanting Shimmy to hear the news from the other kids, I hurried out to the street to find him, and I told him that I needed to talk to him.

I led Shimmy down the block to my office and said, in a low voice, “Shimmy, I have something very, very difficult to tell you.”

Grasping immediately what it was I was about to say, he screamed, “No, Abba, no! Don’t tell me!”

I seated him on my knees, waited for him to calm down somewhat, and then told him the bitter news.

Oops! We could not locate your form.

Comments (4)