Doing My Part

At the time of my diagnosis, when I was 35, I had struggled mightily with the question of whether to tell my parents

Ever since I was diagnosed three years ago with multiple sclerosis (MS), a chronic disease that affects the central nervous system,

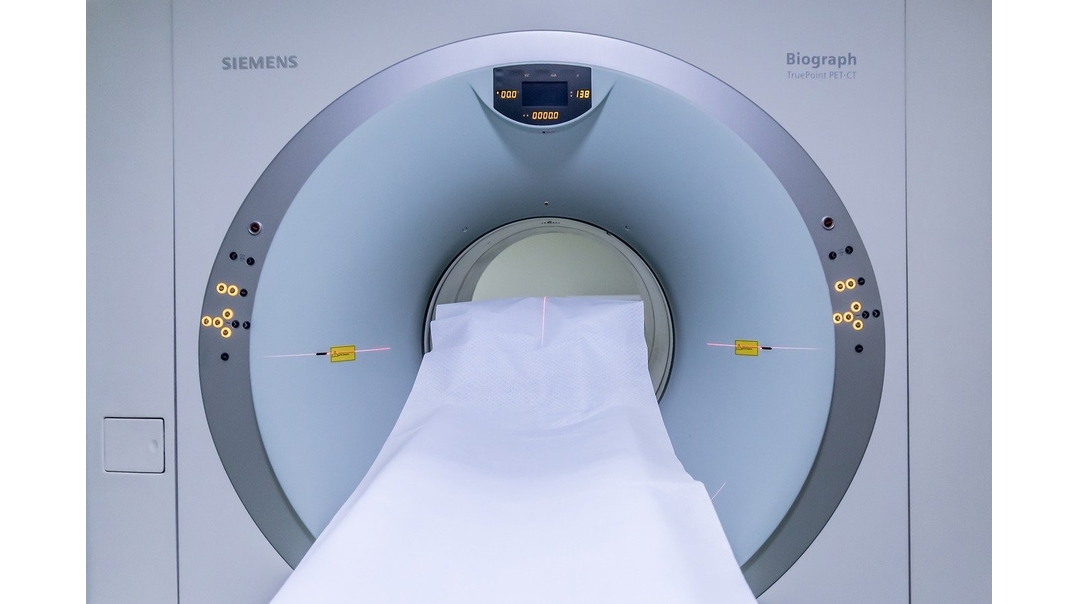

I’ve been required to undergo MRI scans every few months to monitor the progression of the disease and check for any new lesions in the protective layer of the nerve cells of the brain and spinal cord.

In Eretz Yisrael, appointments for MRIs are hard to come by, so you take what you can get. Because MRI machines here typically run 24 hours a day, taking what you can get sometimes means scheduling appointments for midnight or later.

About half a year ago, when I called Hadassah Hospital’s MRI clinic to schedule my next appointment, I was given an 11 p.m. slot for two months later. I accepted the appointment gratefully; it was certainly better than the post-midnight appointments I’d been assigned on many previous occasions.

Several weeks after I booked this appointment, my mother decided to fly in from Canada to visit us in Yerushalayim. As it happened, the evening of her departure coincided with my upcoming MRI appointment. In fact, her return flight was scheduled to depart at 11 p.m., exactly the time of my appointment. Since my mother was unaware that I had MS, I realized that this would require some careful maneuvering.

At the time of my diagnosis, when I was 35, I had struggled mightily with the question of whether to tell my parents. On one hand, I am very close to my parents, and I generally keep them informed of what’s going on in my life. On the other hand, I didn’t want to cause them undue pain. I myself found the initial diagnosis overwhelming, and I couldn’t bear to inflict that kind of suffering on my parents, both of whom were children of Holocaust survivors and carried plenty of that trauma with them.

In fact, my first thought after hearing the diagnosis was, I can’t reveal this to my mother. It will be too much of a burden on her. I envisioned myself as a disabled person in a wheelchair, and I knew that image would break my mother’s heart.

In the aftermath of my diagnosis, I had learned that multiple sclerosis — especially my form of it, a milder form known as relapsing-remitting MS — is no longer the debilitating, devastating illness it once was. While there is still no cure available for MS, in recent years medications have been developed to halt or slow the progression of the disease, and other medications are available that can mask most of the symptoms, allowing sufferers to function well and live basically normal lives. While I was comforted to hear that I could still go on with my life despite MS, I feared that my parents would not be able to find similar comfort. To me, MS was a manageable condition; to them, I knew, it would be a catastrophe.

Had I lived near my parents, I would have unquestionably shared the diagnosis with them despite the anguish they would have experienced as a result, because it would have been far too difficult to hide my symptoms. By the time I was diagnosed, I had been suffering from tingling, numbness, dizziness, fatigue, and other neurological symptoms for quite a while. At first, doctors thought these symptoms were an autoimmune reaction to a viral infection, but after I experienced several acute attacks of dizziness and numbness that landed me in the hospital, they determined that I was suffering from MS.

While I did tell my parents about my symptoms and the initial diagnosis of an autoimmune reaction, because I lived so far away, I was able to downplay the severity of these symptoms and reassure my parents that I was fine. Had they seen me regularly, however, they would have realized that something more serious was going on, and I would have had no choice but to tell them. I would probably have told them anyway, since they could have helped me by watching the kids when I was in the hospital or by keeping the house running when I had to spend the day in bed.

From a distance, all they could do was worry. And worry they would — especially my mother. No matter how much I might reassure her, from a distance, that I was fine, she would never be fully convinced. Not seeing me on a regular basis, she wouldn’t believe that overall, my house was running nicely, my children were happy and taken care of, and I myself was functioning well. Yes, on days when I felt weak, dizzy, or in pain, I couldn’t maintain my usual standards, so supper came out of a package, the floor didn’t get cleaned, and laundered clothing went into the drawers unfolded. But wasn’t that the case in many other busy houses, at least once in a while?

I thought of my friend Bluma, whose parents had recently visited from the US. She had been in a tizzy prior to their visit, cooking and cleaning and making sure her house was in tip-top shape. “Bluma, your parents will understand if not everything’s perfect,” I told her. “They know you have a bunch of young kids. So there’s some dust on top of the refrigerator. So the closets aren’t perfectly neat. Who cares?”

“Yocheved, you don’t understand,” she said. “If my parents lived nearby, they’d see my house pretty often, and they’d know that even if things go haywire on occasion, most of the time we’re in good shape. But my parents come to Eretz Yisrael once every couple of years, at most. Their impression of my house during this visit is the impression that’s going to stay with them until their next visit. So this is my only opportunity for the next two years or so to give them a good feeling about how I’m managing.”

Living across the ocean, my opportunities for kibbud av v’eim were limited. Unlike Bluma, I didn’t feel a need to put on a show when my parents visited each summer. The least I could do, I reasoned, was try to give them nachas, and not saddle them with worry about my health and my ability to cope.

Together with my husband, Shaya, I decided not to share my diagnosis with my parents. When my mother would remark that I sounded tired or under the weather, I blamed it on the baby keeping me up at night. If she caught wind that I wasn’t feeling well, there was always some virus going around that I could attribute my illness to.

I didn’t share my precise diagnosis with my children, either. My oldest was just 14 at the time I learned I had MS, and Shaya and I saw no reason to burden her or the other kids with scary-sounding medical terminology. “Let them have a normal childhood and not feel that they have a sick mother,” I said. “Every mother has days when she’s tired and not feeling well. So I have those days more often than other people.”

I explained to my kids that I had a weak immune system — MS is, after all, an autoimmune disease — and that I therefore got sick frequently and had to go for frequent medical tests. My kids were comfortable with this explanation, and so was I.

Yet I never felt fully comfortable with my decision to hide my condition from my parents. I’m not the cloak-and-dagger type, and keeping this kind of secret didn’t sit well with me. Besides, by keeping my parents in the dark, I was denying them the ability to daven for me and denying myself their tefillos. Was I really doing the right thing?

Years earlier, I had heard a story about a yeshivah bochur in prewar Europe who had fallen ill. Knowing that his mother, who lived in a different city, was widowed and impoverished, the yeshivah’s administrators decided to arrange and finance treatment for him without his mother’s knowledge. When he passed away several months later, they were compelled to send her a telegram informing her of his passing and upcoming funeral.

At the funeral, the mother turned to the yeshivah’s administrators and said, “I am grateful to you for arranging and paying for treatment for my son, but I cannot forgive you for withholding information about my son’s condition and thereby denying him a mammeh’s tefillos.”

That story haunted me.

On the other hand, I often thought to myself that if my mother knew I had MS, I would have to report to her after every visit or test. I would then have the stress of trying to tell her only good news, even though not every test result is good, and not everything the doctor says is reassuring. What would I tell her after hearing from the doctor that there was deterioration in my lower spine? How would I explain that I was switching to a different medication because the shots I was taking weren’t as effective as the doctors had hoped?

A couple of years ago, my sister fractured her leg badly and was sidelined for several months. Each time I spoke to my mother, she expressed to me how concerned she was about my sister and her family. “I haven’t spoken to Chani yet today,” she’d often fret. “I hope she’s doing okay.”

Each time Chani had to go for an X-ray, I would hear from my mother beforehand about the appointment, and afterward about the results. Ha, I’d think to myself. If you only knew how many tests and scans I’ve been through since she broke her leg.

Once, my mother repeated to me my sister’s description of what it felt like to undergo an MRI. “You should never know of these things,” my mother said, “but Chani said it’s like putting Lego in the dryer.” I had to hold myself back from responding that I thought it was more like a car backfiring or a construction site in action.

Hearing my mother fuss about Chani only strengthened my resolve to keep my condition a secret — not just from my parents, but from my relatives, friends, and neighbors as well.

When I was first diagnosed, the hospital social worker had encouraged me to join a support group for MS sufferers, but I had declined. Shaya is a very supportive husband who pitches in to help when I’m not feeling well and offers sympathy and validation as required, plus comic relief, so I didn’t feel a need for additional support. And I didn’t want to be known to people as a sick woman. Nor did I want to see myself that way.

As long as my MS was kept quiet, I was able to go about my life and forget about my condition most of the time, especially since most of my symptoms were well managed with medication. Here and there I’d show up to a simchah in sneakers because of the numbness in my feet, or skip an event altogether because I was feeling dizzy, but life went on quite well without my participation. If I had to miss someone’s simchah, I’d call to wish them mazel tov and simply apologize for not being able to make it — no explanations necessary. Doesn’t everyone have times when they just can’t make it?

My parents usually visit us in the spring or summer, but this past summer my father couldn’t miss work, so my mother flew to Eretz Yisrael herself and spent two weeks in our house. During her visit, we had plenty of opportunities to schmooze, and I felt terribly guilty for hiding such a major part of my life from her. But I felt well during her visit, and since she expressed no concern about my health, I saw no reason to broach the subject.

On the night of my mother’s return flight, Shaya and I drove her to the airport, leaving our 17-year-old daughter babysitting. Since I had the MRI appointment that night, we figured we’d leave for the airport at about 7:30 p.m., park at Ben-Gurion, stay with my mother until she checked in her luggage, and then head back to Hadassah Hospital with plenty of time for my 11 p.m. appointment.

There was traffic on the way to the airport, however, and the check-in lines were long, so by the time my mother reached the check-in desk it was already 9:45 p.m. To our surprise, just as my mother was about to check in, an airline representative approached her and said, “The flight is overbooked, and we’re looking for volunteers to transfer to a 6 a.m. flight with a European stopover. Would you be willing to do that, in exchange for a free ticket?”

“Sure,” my mother said cheerily. “I’m happy to be bumped.”

“Wonderful,” the representative said. “Be back at the airport by 4 a.m.”

Shaya and I looked at each other. “It’s going to be close,” he said to me in a low voice, “but I think we still have time to drive your mother home and make it to the appointment, assuming there’s no traffic.”

My mother turned to us with a big smile. “I guess I’ll be coming back to Yerushalayim with you now,” she said. “And maybe I’ll be here again for Chanukah, now that I have a free ticket!

“But don’t even think of driving me to the airport at three,” she added. “I’ll order a taxi. And please don’t get up to say goodbye to me.”

There was traffic on the way to Yerushalayim, and we arrived home just before 11. Shaya helped my mother with her suitcase, and then we wished her good night and goodbye. When the door to her room was safely closed, I called the MRI clinic. “I’m sorry, I wasn’t able to make it on time,” I said. “Can I still come now? It’ll take me about 20 minutes to get there.”

“You can come,” the secretary replied, “but you might have to wait a while.”

We tiptoed out of the house and drove out to Hadassah Hospital, where we waited until 2 a.m. for the MRI. By the time we left the hospital, it was 3 a.m.

“At least Mommy will be safely gone by the time we get home,” I said to Shaya, yawning.

On the way home, Shaya took a wrong turn — which was strange, because we had done this route countless times before. “I can’t believe I did that,” he muttered.

“It’s late, and you’re tired,” I pointed out.

Our little detour added 20 minutes to our trip, and we pulled onto our block, a sleepy dead end, at 3:45. As we turned onto our block, we spotted a car up ahead, driving slowly.

“Which other meshugener is out driving at this hour?” Shaya wondered. “Did someone else on the block sneak out for an undercover MRI?”

“Looks like it’s a taxi,” I noted. “Wouldn’t it be funny if that were my mother’s taxi?”

“How could it be your mother’s taxi?” Shaya responded. “She left almost an hour ago!”

Sure enough, the taxi stopped in front of our building, and a minute later my mother hurried out. Shaya quickly pulled over to the side of the road and turned off the engine and lights, so she wouldn’t notice us. I felt a powerful urge to run out and kiss my mother goodbye, but I knew she would hardly be pleased to see me at this hour, so I controlled myself. After the taxi disappeared from view, we slipped into the house quietly and went to sleep for a couple of hours.

I had a hard time falling asleep, and it was all I could do not to call my mother in the airport and wish her a safe flight. Instead, I waited until she called me after she landed.

“I’m so happy you didn’t get up to see me off,” she said. “Don’t ask — I was so jumpy, I couldn’t sleep at all, so I went out to your living room to read. I was very quiet, because I didn’t want to wake anyone up. Then I got a message that my flight was delayed close to an hour, so I called the taxi company and told them to come at 3:45. But I managed to sleep on the plane, and now I have a free ticket!”

When I hung up the phone, I couldn’t help but marvel at the Hashgachah. Had we not been late for the MRI appointment, and had we not had to wait after we arrived, we would have come home much earlier, only to find my mother reading in the living room. And had we not taken a wrong turn on the way home, we would have walked into the house at about 3:15, certain that my mother had left — only to find that she was still there. How would we have explained our return home at that unearthly hour, after we had ostensibly gone to sleep?

Instead, Hashem had arranged that we should arrive home precisely when my mother’s taxi was pulling up. She left none the wiser, and we were spared the discomfort of having to start giving awkward explanations.

I felt as though I had received a smile of approval from Above. I was trying to spare my parents from anguish and give them only nachas, but I had always wondered whether keeping this big secret was really kibbud av v’eim. Now that Hashem had helped us guard the secret by keeping us out of the house until the moment my mother departed, I felt comforted.

It was as though Hashem was telling me, “You’re doing your part to protect your parents — I’ll do Mine.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 730)

Oops! We could not locate your form.