Zayin-Ches

| April 18, 2023From mundane to transcendence

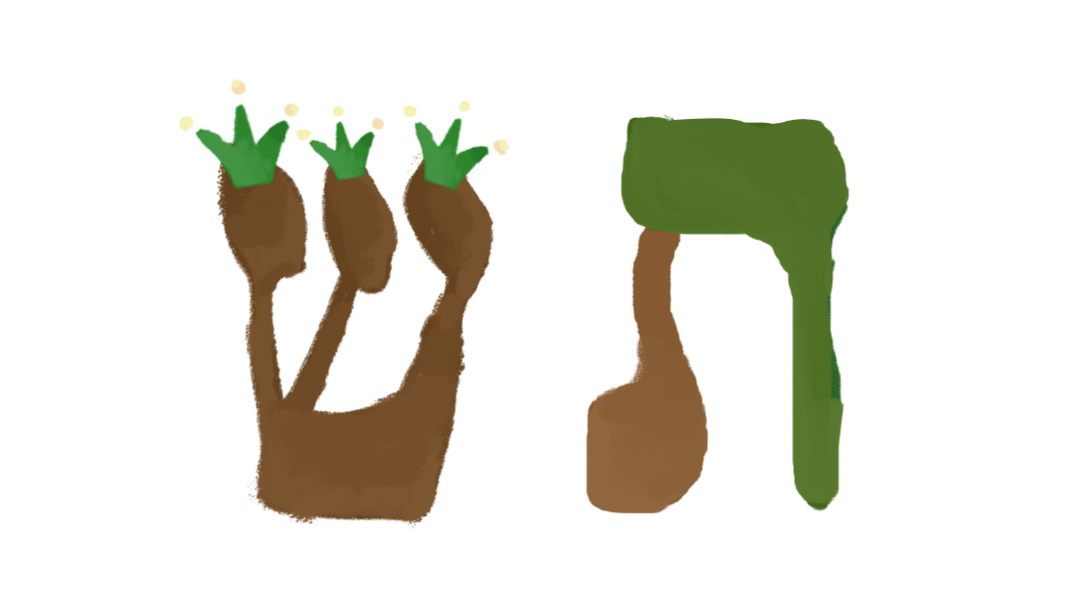

Zayin

Name: Weapon, food

Gematria: 7

Shape: Spear-like bottom, topped with a crown

Middah: Purpose

Every living creature’s food differs drastically from one to the next — and from predator to plant, Hashem takes care of each one. Zayin has the same letters as zayan (sustainer), and Hashem is referred to in Bircas Hamazon as “hazan es hakol” — Sustainer of all.

But while animals find their meals “ready-to-eat,” man’s sustenance must be produced. Most of us aren’t farmers, but we know what goes into putting food on the table. Rav Hirsch explains that the letter zayin also means a weapon, because the struggle for parnassah is a battle of sorts.

When you look at the letters written in a sefer Torah, some have what is called a “zayin” (a crown) on top. Each one of these crowns is actually a miniature zayin, and the letter zayin itself has three of them. The body of the zayin is similar to a spear, as well as to a scepter. The symbol of war is joined with the symbol of royalty, reminding us that as we fight for our survival, the King of the Universe is providing for us.

Adam Harishon was told: “b’zeias apecha tochal lechem — you will eat bread through the sweat of your brow “(Bereishis 3:19). The main staple of Man’s diet, bread, is called “lechem,” which shares a root with the word milchamah, war. Before Adam sinned, it was clear that sustenance came directly from Hashem. Once Adam was given this curse, it became a constant battle for us to see that Hashem is providing for us.

During the week, we work and we eat lechem. But on Shabbos we eat challah, named for the mitzvah of challah, which we perform by separating a piece of dough, to remind us that mitzvos are the purpose of existence.

The physical world is represented by the number six, as many physical objects have six faces. There is a seventh element, that which gives each object a function, and each process a purpose: its content, what’s inside it. The Maharal explains that in life we’re pulled in all directions, but who we are at our core will shape how we make decisions. Will we be honest? Considerate?

When we take time to clarify our priorities and boundaries, we’re able to live according to these values. Shabbos, the seventh day of the week ensures that we’re not just dog paddling through life to nowhere. It’s when we put a “cap” — or better yet, a crown — atop all our physical exertion. On Shabbos our efforts must be put on hold so we can understand what it’s all about.

Earning a living is the quintessential struggle, but the daily “fight for survival” includes all of our challenges: shidduchim, raising children, maintaining shalom bayis, building ourselves. Sometimes we work so hard and see no results; other times we lose track of our goals in the mess of the daily grind. When we stop and ask: why am I doing this? we’re less likely to get riled up by the spilled bowl of cereal or the letter of rejection. We ground ourselves by looking toward the kind of person we’d ultimately like to become.

Ches

Name: Life

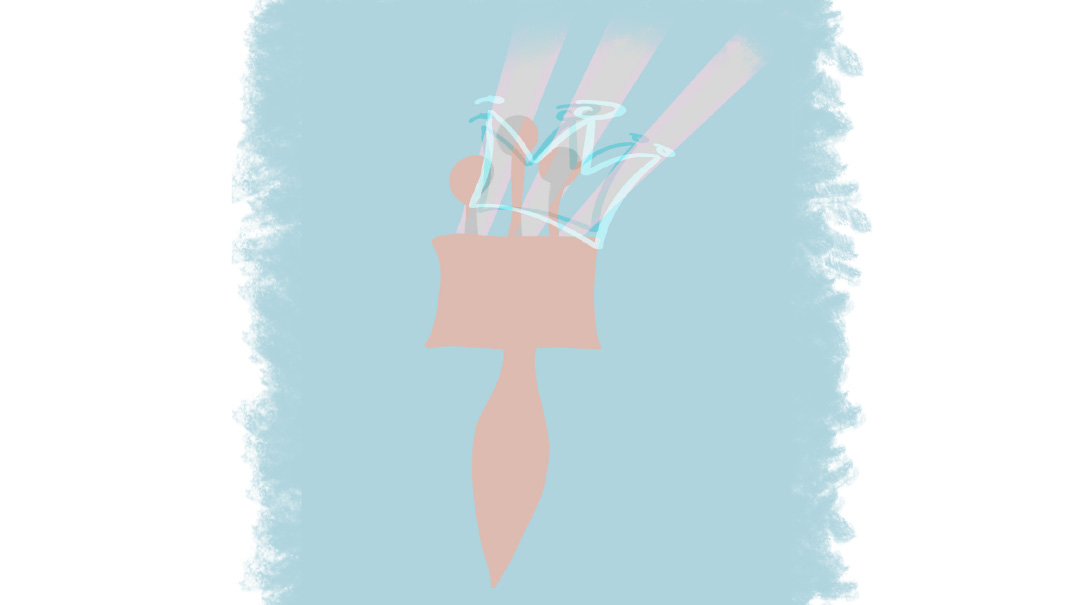

Shape: Arch

Number: 8

Middah: Transcendence

Ches is shaped like an arch, a demarcation of the transition a person makes from their current level to a new one. On the level of eight, a person reaches a deeper state of awareness, ability, and connection (Rav Hirsch on Vayikra 9:1).

We have seven days of the week, which arrive at the completion — Shabbos. As we leave Shabbos, we take some of the spiritual nourishment we got into Day Eight — Day One of a new week.

Throughout the Jewish Year — from one Purim to the next, one Pesach to the next, I’m not who I was last time; a more elevated me is experiencing this year. The siyum haShas every seven years celebrates a culmination, as well as a restart of the process — now filled with greater insight.

Eight is transcendence — connecting us to the supernatural. Sometimes it’s easier to get there than to come back out. Every so often we take a break, enter a new realm beyond everyday existence. We go on vacation, spend time on professional development, go to a shiur, have a long motivational schmooze with a friend — and it’s exhilarating!

But how do we shift back to the “normal”?

We’re not involved in the minutiae of life despite the elevated state we experienced — rather because of it. The entire purpose of the inspiration was to illuminate the mundane path ahead. On Motzaei Shabbos, as I clean up and plan the week, the experience of Shabbos ensures I have my head in the right place.

Ches comes from the root “chai,” meaning life. It can also be translated as paralyzing fear (Rav Hirsch, Bereishis 9:2). Life means movement and change, but this also comes with a fear of the unknown, which can paralyze us. Moving communities, changing careers, growing our family — these difficult transitions lead us toward new opportunities for connection. When we make choices with a connection to the Source of Life, there really is nothing to fear.

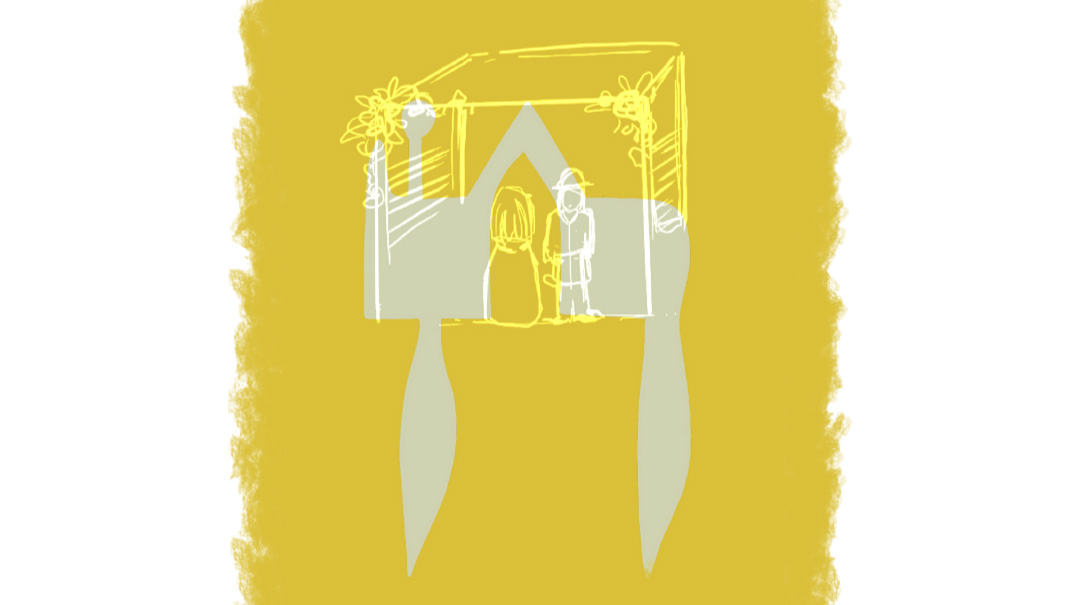

In a sefer Torah, Ches can be written according to the Beis Yosef version (Ashkenazim), made of two zayins connected by a chatoteres — a bridge whose center points upward. The Krias HaTorah explains that this represents two people at odds with each other. In this world of intense competition, it’s normal to push people down in the effort to succeed. But when we commit to higher ideals, we can work to promote ourselves while also building bridges with others — appreciating and even aiding their success. We can collaborate with a competitor, applaud another’s promotion, dance at a friend’s wedding while waiting to find our own bashert.

Sephardic custom goes according to the Arizal — in which ches is formed by a vav and zayin connected by a bridge. Kabbalistically, the vav is “male” and the zayin “female”; they join together to form a chuppah, a home built under the ideals of Heaven.

It’s not easy to rise above our physical tendencies, to get along with people who are so vastly different from us in their goals or characteristics. And yet, when two competitors assist one another, or a couple lives in unity, they access the level of ches and touch something G-dly.

The Connection between Zayin and Ches:

Zayin represents both the physical fight for sustenance and passive trust in Hashem as the Provider of all. The harmonious combination of these two contradictory ideas is represented by the ches — ches is chayim, life, in which we exist in this physical world, while rising above it.

Mindel Kassorla is a teacher, graphic designer, shadchan, and Mishpacha contributor. Her older sister, Cindy Landesman, is the head mechaneches of Shearim Torah High School for girls in Phoenix, Arizona, and the director of its Shaarei Bina adult women's education program.

(Originally featured in Family First, Issue 839)

Oops! We could not locate your form.