What He Does Best

Jason Greenblatt's present: The friends he lost, the lessons he gained, and the gift he hopes to keep sharing

Photos: Naftoli Goldgrab, Mishpacha archives

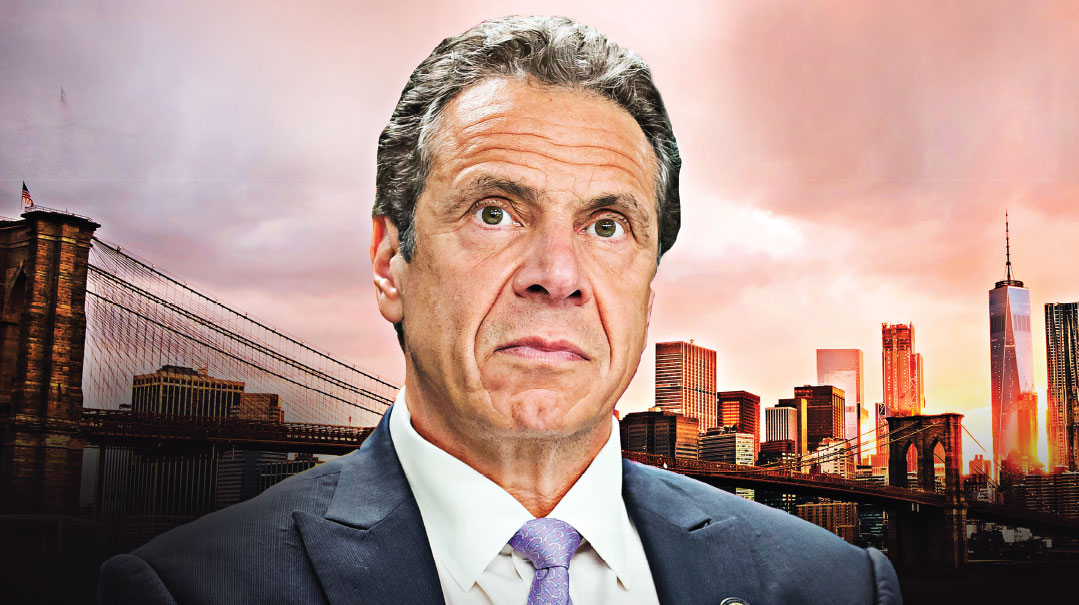

Standing outside on the porch of his Teaneck home so that I can find it on this dark night, Jason Greenblatt, in a sweater and casual pants, looks like any other after-work suburban dad, like he’s just finished a day at the law firm.

And if you know Jason Greenblatt, you know that it’s this — being at home, on his porch after dinner, children coming and going around him — that has brought him back from the heights of power, from backrooms and front rooms and secret military installations, from press conferences and summits and televised assemblies.

Because if you want to leave public life to “spend more time with the family,” it’s much more credible if you were already doing the family thing before you got the job. If your kids were more than props in your campaign propaganda.

The first time I met Jason Greenblatt, he handed me a book he’d written about traveling to Israel with family members. He and his wife, psychiatrist Dr. Naomi Greenblatt, parents of six children (including triplets), are avid travelers. After several family trips, they had it down to a science — and they shared their combined knowledge and experience in their book Israel for Families: An Adventure in Twelve Days, about how to make a family trip to Israel a success, part of a series of three self-published travel books.

About that meeting: In early 2016, Binyamin Rose, our news editor, had a sense that the Trump campaign, being treated as a joke by mainstream media, was very much not a joke, and he encouraged me to develop contacts within the organization. A friend, Abe Zeigerman, introduced me to Jason, a prized real estate lawyer who had worked for Trump for the past 19 years, and served as his executive vice president and chief legal officer, suggesting a lunch at the Prime Grill on Fifth Avenue (since closed), just across from Trump Tower. Binyamin believed. And, I discovered over fish (yes, they did have steak and yes, I wanted it, but the coffee on the way back to Montreal and all that), Jason did too. He was excited that day, because the Secret Service had assigned two agents to Trump headquarters, a sign that maybe other people also saw this as real.

We engaged in what-ifs, enjoyed chatting, and then parted ways, his book under my arm as I left.

Amazing Years

The next part you know, so I’ll skip it, but we did stay in touch after the election. I remember speaking with him one Erev Shabbos, minutes after he’d received a phone call. It had been an unknown caller, but for some reason he picked up — and it turned out to be his boss, the president-elect, encouraging him to come join them in Washington.

“I know how passionate you are about Israel,” Mr. Trump told his longtime attorney. “Come join us and do good things.”

The next part you also know. He made the leap, became Trump’s Middle East envoy — officially, Special Representative for International Negotiations. He did good things, promised to stay two years, ended up staying a third, and then stepped down.

And now he sits back at home in Teaneck, on a brown leather couch in a cozy study, and talks about the joy of sacrifice.

“That first Shabbos after the president formally offered the job, I spoke with Naomi and the children about the difference between opportunity, responsibility, and obligation. We all agreed that was an obligation, so that wasn’t a question.”

But a few months ago, the call of obligation pulled him in another direction.

Did he step away from the job because he didn’t see the “deal of the century” as realistic, as some speculate?

“No.” He’s expecting the question, answering almost before it’s out of my mouth. “I left because, as you know, I planned to do the job for two years. I saw a chance to make a difference, and was ready to give two years away from my family to the cause.”

There was also the pay cut. As the top lawyer for the Trump Organization, he earned an impressive salary. Taking the diplomatic position meant an income that was a fraction of what he was used to.

“We have six children, bli ayin hara, with yeshivah tuitions and the relevant expenses,” he says with his trademark smile, “and for the last three years, we were cutting into savings significantly. Naomi and the children were packing up and driving up to D.C. almost every Shabbos. I couldn’t often get away. It was a crazy lifestyle. They were amazing years, but it wasn’t family life.”

His youngest child, eight-year old Vera, has come in with drinks and Jason sends her back for a third, one more for the photographer.

“The last three years have given me new appreciation for my family, and for my wife, especially. Naomi has been a rock, encouraging me and running the family without me.”

Another hero is his rabbi, Rabbi Shalom Baum of Keter Torah, where Jason davens.

“He was there with level-headed advice, for sure, but in halachah, I may have pushed him into new realms. He came through for me there too.” He grins. “I don’t think anyone has ever asked him about putting on tefillin in sensitive areas of the globe, or what to eat on Shabbos in Riyadh, how to divide up the rice cakes and oranges…”

So what was the catalyst? What made him decide that it was time to move on?

“The truth? When I perceived that Israel was likely headed to a third round of elections. Once I did the math and realized that there’s an impasse and it might mean long months in which we couldn’t move forward, I felt like it was appropriate to step down. I had already stayed longer than I’d committed to.” (Like a true negotiator, he’s careful here. He met Benny Ganz, and was impressed by the man who could possibly be the next prime minister. It isn’t that Jason doesn’t see him as a partner, as many have speculated. “I don’t know him well, but he seems capable,” he says. “Obviously, Prime Minister Netanyahu has been terrific to work with. I have tremendous respect for him. He’s been a critical leader for Israel.”)

President Trump was gracious about Jason’s decision, sending him off warmly. On the day Jason announced he was leaving the post, Trump’s communications team composed a tweet, words of praise for his trusted envoy. Jason came into the Oval Office to formally thank his boss of twenty-two years and President Trump looked at the tweet, before hitting send. “Nah,” he said, “this doesn’t do justice.” He deleted and composed a new one: After almost three years in my Administration, Jason Greenblatt will be leaving to pursue work in the private sector. Jason has been a loyal and great friend and fantastic lawyer.... His dedication to Israel and to seeking peace between Israel and the Palestinians won’t be forgotten. He will be missed. Thank you, Jason!

O

thers have left the administration and been at immediate odds with the president, while some have gone and remained friends. Jason, clearly, maintains warm, respectful relations with his former boss, having been invited back for several ceremonies since leaving the position.

What’s the secret?

“There’s no secret. I’m not writing a tell-all, I have no bombshell revelations. I have tremendous respect for President Trump and his family, and I try hard not to speak lashon hara and to avoid rechilus. I try to be a mensch.”

It’s this last sentence that causes him to shift on the leather couch, as if uncomfortable.

The next day, he will be traveling to Florida, a special guest to the Torah Umesorah President’s Conference.

“There is something… I’m not sure I should mention it in Florida, but it pertains to chinuch, to what we’re teaching ourselves as Orthodox Jews.”

The president, Jason tells me, appreciates the community’s support.

The recent fundraiser hosted by Orthodox communities in the tristate area meant a lot. “It sent a very strong message to the administration — they see that their efforts are noted and acknowledged. The president felt good. But there was a very uncomfortable moment as well.”

Jason, who was abroad at the time, was not at the event.

“Afterward, people came to ask me about something curious. The rule was no cell phones allowed, so all attendees had to hand in their phones, and they got them back in locked phone bags. Not such a big deal, don’t use it, leave it for a few hours.”

“But people went to the bathroom and ripped off the bags, then came back and took videos, photos… it wasn’t right and it was very surprising to the officials behind the event. They didn’t get it. They were perplexed.”

I want to answer him, to defend the bag-rippers, but I know this man and the importance he attaches to decency — and to chinuch.

“I mean, if my children did that,” and his voice suddenly rises, “I would be really upset.”

Then I remember the Thursday night at the Agudah Convention of 2016, just three weeks after the election: Jason Greenblatt came to show respect, a representative of the president-elect seated in the front row at the Thursday night keynote session. The chairman welcomed him by name to great applause. In the lobby, there was backslapping and blessings and regards from this one and that one, old friends, college and law firm acquaintances suddenly emerging from the woodwork. Later that night, he told me that he’d enjoyed being there so much.

Why? I asked.

“Because I liked what the rav from the Mir said in his speech.” The rav was Rav Yosef Elefant, and in his keynote address, he had said that a home has to stand for something: Children have to know that their house is about chesed, emunas tzaddikim, ahavas Torah, simchah… whatever. But it needs an identity.

Now, as I hear Jason’s passion (if my kids did that…), I remember that night.

Speaking about raising children, I wonder how his high-profile position representing a very controversial president affected his children.

“They had it pretty easy,” he admits. “Their friends in school were really good, made them feel proud about it. It helped, of course, that the file I worked on was nonpartisan, meaning that I really worked for the United States government and not one party or the other. The kids were fine.”

He and his wife faced a bit of hostility though, although he says that “as far as I know, I only lost one friend.” Most people in their Teaneck community and shul were supportive — or at least respectful — of Jason’s choice. “But one Shabbos I was going to shul and I realized that a good friend, someone who hadn’t spoken to me in a while, was deliberately crossing the street to avoid me.” Jason shrugs. “Part of what I learned doing diplomacy was that not only does everyone have a right to an opinion, there are people who are literally incapable of hearing another way. It’s sad for them.”

H

e speaks about what he considers the successes of his tenure.

“The president is known as a great negotiator, able to push things forward that others can’t, but what does that actually mean?” He leans forward, elbows on knees. “I’ll tell you. It means that when he threatens something, he carries it out, so that makes the next threat much more real. It’s not just words.”

At one point, Jason was negotiating with UNWRA (United Nations Relief Works Agency) on behalf of his boss, and he conveyed the president’s warning that funding for the agency would be cut if he didn’t see a program that would realistically address improvements in the lives of Palestinians in those wretched camps.

“The president wanted them to stop using Palestinians as political pawns, but they didn’t take it seriously and suddenly, the funds were cut. They quickly learned to take him seriously.”

That’s where he sees the Trump effect. “The new winds blowing across the Middle East, the doors suddenly open to America and even to Israel, are because they realize that this president will follow through — both on threats and promises. He got them to take American words at face value.”

And that’s where Jason’s diplomacy came in. “Once we had them ready to talk, I tried to show them that we’re sincere, we really want to hear their position. It’s not just about enforcing our will.”

Jason is trying to find a humble way to say it. “Look, I’m not better than the many diplomats who worked the region before me, but I think it’s specifically because of my lack of experience that I had an advantage. I didn’t have ready answers and long-held opinions. I genuinely came to listen.”

He reaches for his wallet, withdrawing a slip of paper that is clearly meaningful to him.

“One Friday, I welcomed a group of Palestinian teenagers to my office and we just talked. They were impressive, bright and open-minded, and on a whim, I invited them to come join my family that night, to meet my own teenage children.”

It was Erev Shabbos, and Jason had his wife and children with him on that trip, a rare opportunity — but he felt he had to keep the dialogue alive.

“I called Naomi, who explained to me that in Jerusalem, the stores all close early on Friday and there wasn’t much extra food she could buy before Shabbos, but we made do. They came to our rented apartment and sat there until late at night, just talking.”

The folded paper in Jason’s wallet comes from one of those boys:

I read reports of your departure from the White House… I want to thank you on behalf of myself and the Palestinian people for the honest, fruitful, and candid conversations we’ve had, and giving me access to yourself, your lovely family members, and your house. To be honest, it wasn’t easy for me to interact with you in the beginning, but your friendliness and honesty soon made me abandon my presumptive political fears and count you as a true friend of my people and myself. I will always remember your words in our last meeting, saying that your only reason for staying in the job was to help the Palestinian people and I believe that….

That’s the paper. Under it, there is one more, this one from another Palestinian:

I am grateful for your friendship and feel very proud of it. I am very sad that you will be leaving the administration but hopeful that you will remain involved and have influence. What’s sad is that we never had politicians who did not have a personal interest or anything they wanted to gain, besides advancing the cause. You stand to gain nothing personally and your commitment was genuine.

That is what we lack. We are stuck with career politicians who want to hold on to their positions or benefit from the influence the positions offer them. What we need are people like you with none of them guiding their every move and statement. This explains why you’re capable of being so honest, a virtue completely lost in the world of politics.

Also, I have a message for the Greenblatt family: it struck me that they must have read some unfair assessment of your engagement over the past years. A very big thank you to your family for keeping up with it and offering you space and support to do your job for the sake of us Palestinians and Israelis. The vast majority on both sides is very grateful to you. You should be very proud of Jason, a rare breed of politician, guided by objectivity, honesty, and integrity, only concerned about things that matter and carry weight to create real change.

It’s quiet, and I can’t not ask it. “So l’maiseh,” (because sometimes yeshivish terminology works best) “how can you leave? There’s no one else.”

“I didn’t just leave. I gave two years to this, stayed longer than planned, and now I have other responsibilities.”

“Okay, fine, but what if the president wins a second term and there is a stable government in Israel? Then would you go back?”

He avoids the question and smiles, more at the idea of a second term than my persistence. “I hope he wins again. He was just impeached in Congress, but he’s a fighter. I don’t know that there’s a better word to describe him — that’s his essence. He fights back. He’ll be okay.”

J

ason talks a bit about his own career plans.

“I’m still involved, using the relationships I’ve built internationally to further the cause, but I’m also focused on a new goal.”

He doesn’t see himself going back to work for the Trump Organization, though. “At least not now. If the president isn’t there, the big deals aren’t happening and I’m not needed.”

Jason has addressed many groups and conferences over the last few years and it’s given him a different perspective.

“I learned something about people. If you’re respectful of them and you know where they’re coming from, then they’ll extend the same courtesy and listen to you. I would sometimes try to express ideas that took my audiences way out of their comfort zones, letting them see a bigger picture. Most times, people thanked me for helping them understand something new.”

Most times. Twice that he recalls, people stood up and angrily stomped out of the room.

“Once, in a right-wing synagogue when I used the term ‘Palestinians’ and once in a left-leaning audience when I refused to call Israel’s role in Palestinian territories an ‘occupation.’ ”

Jason laughs and spreads his arms apart, as if there’s nothing to say.

“Look, that’s what I want to do. I know that ‘Jewish unity’ has become sort of a buzzword, but I think I can get people around a table to talk. Naomi has a practice that draws many chassidic clients, she gets it, and we’ve learned so many beautiful things from that community. We Jews have a problem, across the board, in that we’ve forgotten how to talk to each other.”

Jason has read Daniel Gordis’s book, We Stand Divided: The Rift Between American Jews and Israel, but he doesn’t think the situation is hopeless. “It was very thoughtful. The extreme left is unwilling to engage, that’s true, but if you talk to one group at a time, one person at a time, you can break a lot of resistance and people who find themselves to be extremists — to the right or left — realize that they aren’t.”

Jason knows that many Jews, especially liberal-leaning Jews, aren’t fans of the current president. “So because of that, they wrote off everything this administration is doing. Still, we’ve had success in talking to them, helping them understand that seeing a good policy for what it is doesn’t mean they have to appreciate every single tweet.”

There have been many special moments during Jason’s tenure as Special Assistant to the President of the United States. Shivah visits with bereaved parents following terror attacks. Meetings with the most powerful people in Muslim society, Israeli society, European society, and, of course, American society. Private sessions at which he received brachos from Torah giants, such as Rav Gershon Edelstein, who assured him that his work on behalf of Klal Yisrael would not come at the expense of his children.

But the moments he treasures most were those spent with any two people who didn’t understand one another, couldn’t understand one another, and then, with patience and decency and the right words and what Teaneck dad and attorney Jason Greenblatt calls “something, a gift from Hashem that allows a channel to open,” they started listening to one another, really listening.

And it’s there, at the intersection between mistrust and perfect understanding, that he wants to hang out, doing his thing.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 795)

Oops! We could not locate your form.