Veiled Truth

It was Abba who’d told her to follow her heart. If it was kosher, if this is where she came alive, she should go for it

She is drowning her challah in dressing when she realizes she never really knew him.

Mmm, good, who made this? she thinks, almost says aloud, while one of the uncles is talking — about Opa.

Ellie looks around. No one’s eating. Aunt Shulamis is picking at the corner of her eye. Oma sits at the head of the table, her eyes like dark, endless tunnels. Uncle Gershon on one side, her father on the other. She watches Oma’s expression, empty, faraway, the way it doesn’t change when Uncle Gershon takes his mother’s hand.

She looks at the laden platters of food, Aunt Shulamis’s crockery laid prettily at each place. Some people, Uncle Srul, the cousins, have filled their plates. But they are toying with the food, like it’s the enemy and the cutlery are their weapons.

Salad swamps her plate. She pushes it away, swallows, and tunes in.

“He spent his golden years in Eretz Yisrael — fifteen years. He left the States where he had everything, where he’d married off his children, where everyone knew and respected him, where he had his place in shul, in the community, and he started again in Eretz Yisrael. That was our father. And when his condition deteriorated and we had to bring him back to New York, it was a bechinah of al karchacha… And he was here, near us, only for half a year…”

Just half a year. That was the grandfather she’d known. A man in poor health, who said little.

She’d taken a shift here and there in the hospital. But she’d never really spent any time with him. And here she is at the shloshim seudah for Opa. She’s twenty-one; he was more than sixty years her senior.

“Yehi zichro baruch…” the uncle finishes.

Loud silence.

“Shkoyach,” Uncle Srul says finally.

The men take it up, “Shkoyach, shkoyach.” Something to say.

The cousins peck Oma on the cheek and leave, swinging handbags, couples headed for their cars.

Ellie’s parents take longer. She waits for them. She’s the youngest of the cousins, last of the generation.

She’ll be married soon, too. She looks at the ring. It still startles her to see it there, resting on her finger like it belongs. It’s two weeks old.

David had wanted to drive in from Baltimore for the shloshim seudah. She’d told him not to. Some of the cousins hadn’t made it to their vort, and she didn’t want it to become about them — Mazel tov, welcome to the family… She couldn’t sit here at the table with her chassan, in their little bubble of happiness, when it was about Opa. And Oma.

She looks up. The table’s emptied, Abba’s siblings are talking in the living room. Only Oma’s still sitting there at the head of the table, with Helena, her aide.

Oma, who hides away; Oma, who forgets. She’d taken the move back to the States so hard, it had unsettled her, unmoored her. And now, Opa’s death.

Ellie goes over to Oma and sits beside her.

“Oma,” she whispers.

Her grandmother turns.

She waits for something, the ghost of a smile, recognition. Nothing.

“It’s Ellie, Elisheva,” she says.

Oma’s mind is starting to fade, but she’d recognized Ellie last time.

She searches Oma’s face. Trembling chin, wrinkled skin, huddled into herself. Oma is a prune, Ellie realizes, the purple zest of her life dried out, leaving her shriveled and colorless.

“Elisheva,” she says again.

Opa is gone. She hadn’t used the short chance. But Oma….

“Agoraphobia,” Abba had said. It was something Oma developed these last few frenzied months. She wanted to stay in, stay home, shut in and safe.

“Ellie, come over here,” her mother calls.

She joins the circle — Abba, his siblings, and their spouses.

Uncle Srul, oldest, talks straight to her. “So, Elisheva, you know how independent Oma is.”

What did she really know about Oma?

“She’s been here, at our home, for a good few months,” he indicates his wife Devoiry, “while Opa was in the hospital, and then for the shivah. She wanted to go home, to her own place, ever since, but ach, who could think? But now, G-tt knows why, she’s insisting on it. She’s not doing so well, we really need to sort something out….”

Why are they telling her this?

“So we were thinking, we’ve got Helena, the aide, of course. But Oma doesn’t like her around too much. Would you sleep at her house for a week or so, until we sort something out? We’ll be around during the day, me, the aunts, like we always are. It’s just the nights. It might do her good being back in a familiar place for a bit.”

Aunt Shulamis nods. “Yeah, you know she lived on Seventeenth Avenue for decades before they moved to Eretz Yisrael,” she adds. “For Oma, what does time mean? Fifteen years back is not such a stretch, it’s still her home….”

“I mean, you do realize, she just got engaged,” Ellie’s mother says. “She’s getting married soon. So obviously this is a very temporary arrangement.”

Ellie smiles at her mother’s indignance.

She looks back at Oma, still sitting at the table.

“Of course, just until we make other arrangements,” Uncle Srul says resolutely. “We’re working on it.”

Ellie sits on a dance mat, legs tucked beneath her, with Rashida, Janet, Sarah, and the others, the twelve of them forming a half circle on the floor around Michelle, their facilitator.

“Relationships can be compared to a dance,” Michelle is saying. “There’s singular dancing that involves just one person and there are dances that allow for others to join.”

Ellie looks around the small, women’s-only group. Rashida in her burka, Sarah who’s crazy double-jointed, Dayita, Indian and slender. Multiculturalism is alive in Brooklyn, in this advanced dance-movement therapy track, at least.

“A dance is a series of movements that are combined and often repeated, where two people move in sync with each other’s steps,” Michelle says. “What do you think gives you your ‘steps’?”

Janet raises her hands. “Your attachment style?”

“Good. Yes, your own attachment style, and how it relates to the other’s style, of course — the dance that’s happening. We’re bound to talk about it, it’s an easy metaphor to visualize, and in this class…”

Ellie almost snorts. Dance was the great metaphor. Because it worked. People didn’t realize how predictable they were, how they were so likely to make the same mistakes again. After a year in a dance-movement program, you start to see everything as a dance.

“You know what, let’s bring it to life, through movement….”

She looks around. “So Sarah, let’s say you’re avoidant.”

“Okay…”

“And Ellie here is ambivalent.”

“Who, me?”

“Yes, ma’am,” Michelle says. “What might that look like in a dance?”

They get to their feet, Sarah and Ellie, stand in the middle of the room.

Michelle puts on the music. Light snatches of sound, like a caress over the piano keys.

Sarah backs away. Avoidant. Ellie edges towards her. She tiptoes closer, curves her hands.

Sarah slithers away along the wall.

“Go, girls,” Michelle whispers, and the music sweeps up, angry chords, strident and loud and everywhere.

Ellie glides all the way over, supplicating hands — Sarah turns towards her.

Ambivalent, Ellie, hey. She arches back, the tiniest movement, a shiver of uncertainty. Back, forward, back again. The music stops, and both girls drop to the floor.

The others clap.

“E-llie! Sa-rah!”

They grin at each other.

“Great job, girls.” Michelle says, as they take their places back on the floor with the others. “So yes, that’s what avoidant-ambivalent attachment styles could look like in a relationship. The dance steps are important because if people could only see themselves, see the moves they repeat over and over, it would be so clear to them what needs changing.

“Of course, in the dance, you’re getting the main moves, the intense bits. What Ellie and Sarah did there wouldn’t have been one exchange, it could’ve been a day, more likely a year, of pretending, thinking, trying, like Ellie did, but then pulling back, and Sarah just slinking away, keeping away.”

She holds out her hand to the group. “Thoughts?”

The room is still. When you’ve seen it like that, it’s powerful, you can understand without words, Ellie thinks. “Next session we’ll look at changes. How one partner changing the steps affects the other… See ya then.” Michelle waves and leaves the room.

“That was good, Ellie,” Dayita says. “The dance, it’s in you. You told us already, but seeing you in action….”

They’d had this conversation once, at the beginning of the course. They spoke about why they’d chosen the track. Janet said she was here because of the expression; because mind, body, and spirit are connected. Ellie said she was a dancer through and through. And Rashida had concurred, said she had dreams of dancing on the world stage. Dreams she had to put to rest because of her background. Ellie could understand.

Dayita, the Indian girl, had said how short the shelf life of a professional dancer was, anyway.

They’d understood her, some of them had, about what dance meant to her: being the dance, becoming the dance, though sometimes she didn’t even understand herself.

“Yeah, thanks, it was fun. Interesting,” she says to Dayita, and gathers her stuff.

It was. She’s lucky. The Jewish Learning Institute had hooked her up with this specialized women’s track recognized by the American Dance Therapy Association. She got to train to do what she loves in a way that’s in sync with her values.

Ellie walks out into the cold air.

Her mother thinks she’s crazy. She doesn’t understand a bit of it.

It was Abba who’d told her to follow her heart. If it was kosher, if this is where she came alive, she should go for it.

Oma used to dance, Abba had said. She’d go to weddings, to be mesamei’ach the kallah. She’d do the broigez tanz, with a waving handkerchief and a comical expression. She was the life of those early post-war weddings in a Williamsburg of survivors.

Ellie crosses the street and heads for the subway.

These days Oma doesn’t go to weddings, doesn’t go out at all.

Oma, the life of a wedding? Life of anything? Oma, dancing?

Ellie ducks down the stairs, into humanity. Where is her Metro card?

Oma. She’s going to sleep over there tonight.

“Hi, Oma.”

“Hello, Elisheva.”

She clutches the little carry-on suitcase, wheels it into the house with her.

Aunt Shulamis is there, puttering in the kitchen. She sniffs a carton of milk, wrinkles her nose, and throws it out.

“Ah, hello, Ellie.” She waves. “Oma’le dear, Elisheva will be staying with you tonight, like we said.”

“We did?”

“Yes, yes. I better go now.” She gives her a little pat. “I’ll leave you two to get acquainted.”

She lowers her voice and points around the kitchen. “That’s Oma’s medication, she goes to bed around 10 p.m., make sure she takes it all beforehand.” She indicates the phone on the wall. “Give us a call about, well, anything, you know Oma can get scared, but she should be fine. She’s had a good day. Bye, now.”

The door shuts. Ellie turns back and faces Oma.

Get acquainted, okay.

“How are you, Oma?” She sits down beside the old woman.

“Danke G-tt,” Oma says automatically. “And you, Elisheva? What are you doing now?”

Ellie takes a couch cushion, kitschy and stiff, and tries to squeeze it into softness.

“I… I dance.”

“Oh.”

It’s just the syllable. Nothing else. Not I used to dance too, or stories from the shtetl, or about weddings on Bedford Avenue.

Maybe she should say more? Explain the dance therapy track, what she’s doing. But really, for all Abba says Oma used to dance, what does her grandmother know of her world?

She hardly talks. Her hands, her feet, are old and brittle.

Ellie the dancer, Ellie who comes to light and life in the music. Wouldn’t Oma find it frivolous? She could never relate.

And the therapy bit? Ellie subdues a piece of floral cushion and rolls it between her fingers. Therapy is a luxury, she realizes. The cushion jumps back into rigid position. Oma never had that. She was from another world. Where you had to be as firm and unassailable as this cushion.

She sighs. Oma heads for the bedroom with its brown, papered walls, overly flowered. She takes her pills in silence.

“You’ll stay here with me, yes?” She points to the other bed.

She hadn’t thought where she’d sleep, but not right here, in Oma’s room, in Opa’s bed.

The old woman looks up at her, small and helpless as a child.

“Sure,” Ellie says. She creeps into the other bed, trying not to breathe in the smell — of old age, of Opa, of Israeli laundry detergent — as she slowly eases into sleep.

David calls on the way to class.

“You’re sleeping over at your grandmother? See, I knew you’re special….”

She laughs a little. So sweet, but it makes her grin.

“Well, maybe. The thing is, making sure she takes her pills, sleeping over so she feels safe, it’s all nice and good, but I don’t even know my grandmother. I didn’t grow up with her. She’s a stranger, really. An old, vulnerable stranger.”

“Hm. But Ellie, it’s never really just about the practical, at least it doesn’t stay there. It’ll come, the relationship, I’m sure it will. Have you — tried?”

She checks her watch, quickens her pace. “What do you mean?”

The subway’s up ahead. If she wants to catch her train, she has exactly one minute before she has to submit herself to the escalator and lose reception.

“Being you. Telling her about your stuff. Work, training, us….”

“I don’t know.”

“It worked on me. I was a stranger too.”

“Oh, David.”

“Don’t stand there, you’re blocking the way.” A man holds out a hand, irate.

“ ’Kay, I gotta go, but I’ll think about what you said.” She giggles. “Stranger.”

Late at night she wakes up. Where is she? The scent of Israeli laundry detergent. Opa’s bed. In the moonlight she can see that the other bed is empty.

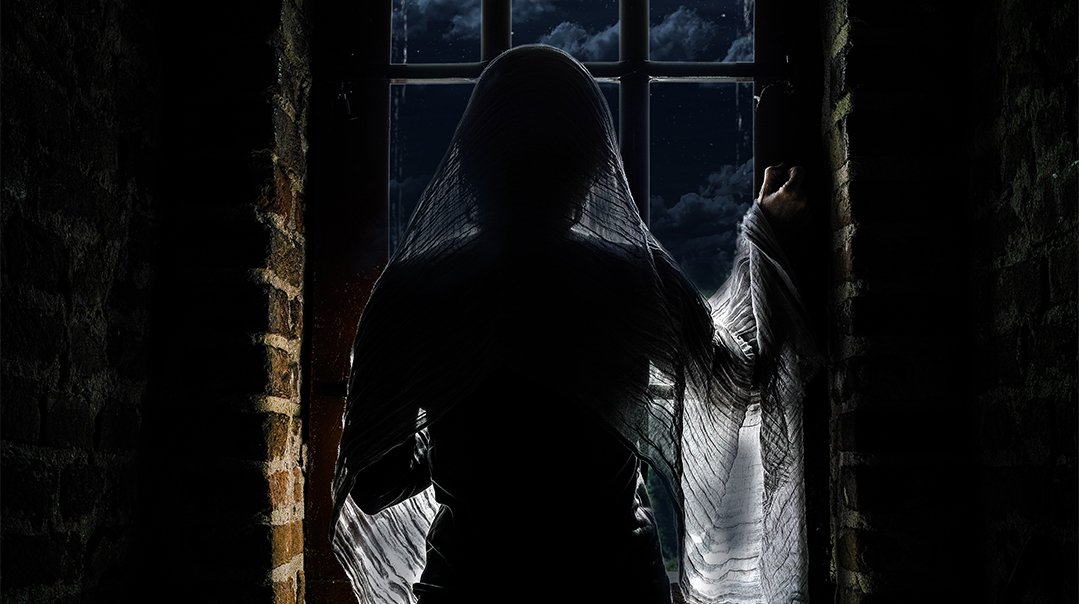

She hears rustling. Tissue paper, then tulle. Oma removes something from an old trunk at the foot of her bed. A haze of white transparency, like a limpid ghost. She is dreaming. With sure hands, Oma clips the long white ream of fabric to her head. It’s a veil that scallops around her, drops past her waist, almost to her ankles. Oma takes a step to the mirror in the corner of the room. She looks into the oval that throws back her reflection and Ellie can’t see if her eyes are open or closed.

In the mirror she is transformed. A bride. A slowly sashaying, dancing bride. Hands raised, fingers curling, tapping her feet to a rhythm in her head. Her feet wend and weave, forming triangles, two, and two more. She lowers her hands, holds them out as if to take someone else’s and Ellie realizes that she is dancing in tandem.

She sees two Omas. But Oma sees someone else.

Oma spreads her arms and the veil waterfalls around her and Ellie can see just the blinding whiteness, then blackness of her eyelids, and she is claimed by sleep.

She blinks in the morning light. A neat square of duvet, Oma’s bedclothes deftly folded.

Something niggles. “Oma?” she calls. “Are you alright?”

“Danke G-tt,” comes a voice from downstairs.

She dresses, grabs her bag, and flies out of the house. “Sorry, Oma, I gotta run to class. Helena’s here.”

It’s only in class, watching Michelle demonstrate something, the curl of her hand, waves formed from one movement and another, that she remembers.

Oma was doing something like that. In the dead of night.

“So you have to take the cue from the client,” Michelle says. “Allow the client to express themselves through movement because movement is a language. It’s our first language. Nonverbal and movement communication begin in utero and continues throughout the lifespan. But you also need to see beyond the movement, a holistic view of the whole person. What they’re saying with their eyes as well as with their feet.”

Ellie raises her hand. “Can — can you have elderly clients?”

Michelle blinks.

“I know, I know, you were saying to take the cue from the client. But what if they’ re elderly, what if they don’t know what they’re doing?”

She’s blabbering. What is she asking? This has nothing to do with the class.

“Ellie?” Sarah hisses.

Ellie ignores her.

“Look, Ellie,” Michelle says, “many of your clients won’t know what they’re doing, why they’re doing it. It’s their outlet, their expression, and then you can talk about it, decide together what it means….”

She gives Ellie a tight-lipped smile, and consults her notes again. “So where were we….”

Ellie tunes her out. Oma was dancing. Oma, of the broigez tanz of fifty years ago, was dancing, lithe as cat. Or was she dreaming?

When she comes home for dinner, her mother is waiting, something in her hand.

“This just arrived. Can we go through it together?”

She waves a notebook. The Kallah’s Guide: From Aisle to Aisle.

“So where should we start? Housewares? Sheva brachos? Appointments?”

“Ma, I’m hungry.”

“But this is way too exciting.” Ma flips a page. “My last chasunah to plan. We’re gonna do it right this time.”

Ma goes to the stove and ladles some soup. “Here.” She plunks it down in front of Ellie. “Let’s start planning. Gisele’s is having a sale next week….”

“Mm,” Ellie says, taking gulps of soup.

“I’ll take that as agreement, young lady. I know you don’t love shopping, but you do like looking good, and it can’t happen from nothing.”

Her father comes in then, drops his briefcase on a chair, smiles at Ellie. “Hello, Kallah. How was Oma?”

Ellie thinks of water and tablets, her grandmother drinking and swallowing like a good girl. She thinks of gentle snores — last night’s dream?

“Fine, I guess. Helena’s there in the mornings when I go off to class. I’m managing the nights.”

“I’m sure you are. But like we said, it’s not a long-term solution at all. I’ve spoken to Srul and the others. There’s nothing to it, Oma would be best off in a nursing home at this stage.”

“Really?”

“Yes, don’t you think so? Now that you’ve been there for a week or so? She’s not herself anymore. She forgets, she doesn’t know, she thinks she knows. Not to mention the agoraphobia. You know, Srul, Shulamis, they were saying it might be best if she doesn’t come to the chasunah.”

Ellie puts down her spoon. “Do you mean that? It’s been going okay, I thought. I mean, I’ve been breezing in at nights, rushing out in the mornings. But Abba, I really think it would be best for Oma to stay in her own home now.”

There’s conviction in her voice, and she doesn’t know why. Hands in the mirror. What hands? It was only a dream.

“I’ll speak to Srul again,” her father’s says. “You’re a good girl, but—”

“You’re getting married soon,” Ma says, pointing to the Aisle book.

Ellie grins faintly. “So they say.”

She’s late to Oma Motzaei Shabbos.

Oma is at the window, looking out at a patch of concrete. Orange light spills in from a streetlamp. Glaring and urban.

Maybe a nursing home would do her good? Flowered walkways, plants on a porch.

She looks at her grandmother, installed on the couch, clutching an armrest. Her armrest. Her house. Paisley patterns and beige walls. The space she’s holding onto, this two-story box she’s resigned herself to, constrained herself to — because it’s the only place where she still has control, Ellie realizes.

“Come, Oma.”

Her grandmother leans in and Ellie pecks her cheek, and leads her to her bed.

The walls papered in sepia tulips, the trunk at the foot of the bed. This room, this home, it’s a small foothold on the past, Oma’s last domain, before a confusing city beyond.

Ellie tucks Oma in, goes back downstairs.

Text from her mother: Gisele’s tomorrow?

She yawns. Gisele of the appraising eye, looking you up and down in a dress, and gauging the way you hold yourself, the brand of your pocketbook, your last name, before naming a price.

But she carries a mean selection of evening wear. Italian, she claims.

Sure, she texts back.

Sunday is her one day off, the one day she doesn’t have to skedaddle out at dawn. Which is just as well, because it’s also the day Helena doesn’t come. She’s free to linger around until one of the aunts turn up.

She leaves her phone to charge in the kitchen and tiptoes into bed. It’s late, maybe 2 a.m., and she is almost asleep, when there’s a rustle. A tug at the trunk, a long veil clipped on, and an old woman who won’t say much, who won’t go out, dancing, dancing in the mirror.

Ellie gapes, taking it in — the fluid motions, the outstretched hands, empty hands. She’s frozen, petrified into sitting-lying position.

She is not sleeping. She is not dreaming. She is not. She wants to push the button on the alarm clock to see the time, to see blue holographic numbers, the present, in this spooky fantasy of the past. But she doesn’t dare.

Swaying hands, a brown, musty room, an eighty-five-year-old bride in the mirror.

They wouldn’t believe her. Ma, Aunt Shulamis, Uncle Srul. Never. Her phone. She should video this? Sacrosanct, but she gropes on the bedside table anyway, because she has to prove that Oma needs help. That Oma visits a plane that doesn’t exist, a world out of a trunk, where — she looks back in the mirror — it’s the only place she really smiles. To take that away from her….

The bedside table is empty. Her phone is downstairs, charging. Oma triangulates away from the mirror and back into bed. Ellie’s heart beats-beats-beats in her ears. It’s a long time before she sleeps.

The familiar ringtone comes from far away. Earth to Ellie. Her phone is ringing. She drifts into wakefulness. Oma’s bed is neat as a pin, awash in sunlight.

“Is this yours?” Oma hands her the ringing phone.

“Uh, hello?”

“G’morning, Ellie, it’s Aunt Shulamis. I didn’t wake you, did I?”

She clears her throat. “No, no.”

It’s never something to admit to, even if it’s patently obvious.

“Okay. I’ll be there in an hour or so. Can you make sure Oma’s eaten, that she’s dressed, uh, presentably? I’m bringing a caseworker from the nursing home, Doreen. She wants to make an initial assessment….”

Ellie’s still coming to. Nursing home. Oma. Veil from the trunk.

“Oh, okay.”

“See ya soon.”

They didn’t realize, none of them did. A new place? Oma has too many demons to deal with right here. What did this trunk even mean to her? She grips the edge, tries to pry it open. It’s heavy, how did Oma open it in the dead of night? In her sleep?

The wooden top gives way and Ellie looks inside. She half expects a ghost, an apparition, but it’s only the veil, folded over, beautiful lacework.

She hears footsteps in the hall. She should fold it back. Close the trunk. Forget it.

But Oma’s stuck on this, and Ellie’s the only one who knows, who’s seen. She clutches the lace and finds her guts.

“What’s this, Oma?”

Oma whirls around. “What?”

She holds out the old tulle. “This. This veil.”

“Oh, where did you find it? I didn’t know I still had it.”

Ellie blanches.

Didn’t know?

Oma takes a corner of the veil, traces the pattern with her finger, a wonder in her eyes. “It’s been so long…”

No, it hasn’t. It’s been, what, less than 12 hours?

“My husband, my Shneur, he made me keep it. It was the one thing he gave me for our wedding. This long piece of lace he’d traded I-don’t-know-what for. Zelma, a girl from our village with nimble fingers, she attached the comb. My wedding dress was little more than a man’s white shirt with a few tucks at the waist to turn it into a dress. But I had the lace all around me, a veil like a cloak. In the DP camp that night, I was a queen.”

“Oh, Oma.” Ellie takes her grandmother’s hand.

She is remembering, talking at last. She was a girl once too, aged before her time. A girl who still fancied herself a princess, even with all she’d seen.

Ellie looks up, searches Oma’s face. “Tell me more,” she says.

“The veil, it gave me wings. I danced inside it. Tancerz they called me, dancer. But I also cried. Once, before the world turned mad, we’d created a dance, my sister Reina and I, an intricate two-people dance. We were going to surprise everyone, we decided, we’d present the dance years on, at our weddings. First at hers, for she was older than me, and then at mine. But Reina wasn’t at my wedding. There was only Zelma from our village. Reina was gone. I never saw her again. That night, I danced our dance alone.”

The veil flutters to the floor. Ellie takes both of Oma’s hands and squeezes them.

She danced alone, then. And she dances alone now too, in the depth of dreams. But maybe not, maybe she thinks she’s dancing with Reina, with the woman who holds out her hands in the mirror?

She takes the frail hands and draws them into a hug. Then she buries her head in Oma’s shoulder.

Poor, poor Oma’le.

Her phone rings from the floor. Probably Aunt Shulamis, to say she’s here, with Doreen from the nursing home.

“No,” she says. A thousand times no.

Ellie thinks of Oma in a new, whitewashed, sterile nursing home room, reaching for the veil in the dark, in the nether of a dream. Finding nothing, screaming, waking up. All her worlds colliding. No sister, no husband. No one there, not even Ellie.

She shakes her head, lets the phone keep ringing.

Ellie reaches for the tulle. “You know, Oma, I’m getting married soon.”

“Really?”

“I — I don’t know if you’ll come….” Suddenly she wants her grandmother to come more than anything else. “But maybe… maybe you’ll let me wear your veil?”

Oma snatches back the lace. Her face closes. “No.”

“Okay, girls, your turn. Time to role-play a session.” Michelle rises from her seat onto clicking heels, Cheshire-cat grin.

“Dayita, you’ll be the therapist.” Michelle nods in her direction. “Now for the client… Janet?”

“Uh, no. Not now, please.”

“Rashida? No, you had a turn already. Ellie?”

“What do you want me to do again?” Ellie asks. “Expressive motions, and Dayita is gonna interpret them?”

“Help you interpret them,” Michelle amends. “It’s about the client.”

“Okay, well, why not?”

Dayita’s sitting in Michelle’s chair, up front. Ellie shuffles over.

Dayita clasps hands together, bends forward. “So, Ellie, what brings you here today?”

“I don’t know.”

The girls laugh.

“Expect your client to say that,” Michelle says.

“That’s okay,” Dayita says. “Here, let me put on some music. You just start to move to the music.”

“Good, good,” says Michelle from the side.

“Whatever,” Ellie mock rolls her eyes, starts to rock on her feet, side to side.

“Okay, Ellie, just let go. Move.”

Ellie closes her eyes. Unkinks her feet. Breathes.

Dayita raises the volume, and Ellie finds her feet forming a triangle. A new, familiar, three-point step, three taps and three more. Left, left, right, right. Her hands are moving in tandem with her feet, swishing out hills and valleys in the air. In half a minute of music she’s found Oma’s dance inside her.

“Beautiful,” the others breathe.

“Sophisticated, sheesh,” Sarah says.

Dayita turns to her from the therapist’s chair. “Where did that come from?”

“From my grandmother,” Ellie bursts out. “I didn’t even know I knew it….”

“What does it mean? To you?” Dayita says.

Michelle steps in. “Let me put this to the class. What did you see there, girls?”

“Longing?”

“Hope, joy—”

“Disappointment…”

“Ecstasy.”

Ellie sits on the floor, still panting. For Oma, it’s all of those things. What about for her?

Michelle looks at her and back at the group, “Expect this to happen, too. When you’re in training, when you get into it, your own stuff is going to come, your own dances, your own journeys. Ellie, take a deep breath in. And out….”

Michelle does some calming routine that she doesn’t even hear.

The sessions ends, Ellie flies out. She knows what she has to do.

“I know you might not come to my wedding, Oma.”

“You’re getting married?”

“Yes.”

Oma’s face is wreathed in a smile. A fresh moment of nachas, like a new dandelion plucked from the grass, and the slow joy of blowing seeds into the wind. She’s living this moment.

“Oma, it’s in two weeks, and I — I know you don’t like crowds,” Ellie says gently. “You might not come. So let’s dance here. Let’s have a wedding dance together right now, okay?”

It’s late evening. Harsh orange streetlight bleeds through the window. Somewhere, there’s a sunset they can’t see. Oma takes her hand and falls into a step, and Ellie summons the dance that she knows almost intrinsically. They dance the mirror dance, the sister dance, together, three-point tap, sway to the right, sway to the left. Oma begins to hum.

The tune she hears in her head at night.

They dance on the carpet, while night falls around the old, brown house.

“Reina,” Oma says.

“I’m Ellie,” she says quietly.

But it doesn’t matter. Oma is smiling — with her eyes. She’s in a new moment, another new moment. Unreal, but real and firm as the grasp of their hands.

In the next few days, people come and go from the house. Aunts and uncles and social workers. Ellie wants to rail and rant and tell them that Oma’s haunted by the past, that maybe she’s only just beginning to heal, that it could be a long process, and the last thing they should be doing to her is moving her around. But there are also appointments, nerves run taut, she finds herself at the sheitel salon, meeting the musician, the caterer, dizzying choices and endless trips to stock up her new apartment. And they’d never believe her. Dream-dancing? Ma? Aunt Shulamis? They’d think she was the one going crazy.

Five more nights with Oma. Ma thinks it’s ridiculous. The kallah should be home already. “This week, that’s it,” Ellie had said, and Ma threw her hands up. Besides, Oma’s move to the nursing home is slated for a couple days before the wedding, and the arrangement works for everyone.

Between a gown fitting and a phone class with her kallah teacher once Oma’s safely in bed, Ellie steals another dance with her grandmother.

They glide together, more than sixty years between them, but they share a grace.

Oma’s waves her arms, flicks bony fingers. Ellie swallows, does the same.

I come from somewhere, she thinks gloriously. Ma never understood what dance is to me, why I had to take it quite so far. But it’s a part of me. Of us.

Oma smiles without words, almost as if she can read her thoughts.

Ellie stays the five nights. She is exhausted, rushing around all day, crashing in there at night. It’s only on the last day that she realizes, it’s been five full nights. No rustling, no tulle, no pre-dawn sleep-dancing.

Her alarm goes off early and she watches Oma sleep. Calm in sweet slumber, breathing evenly.

Could she have left it behind, the beasts of the past she’d been dragging with her all those years, all those isolated nights?

Could Ellie have helped her leave it behind?

It’s the last time, the last opportunity before her wedding. She’s going back home and the aunts are going to be over all day. Oma’s moving to the home tomorrow. She might come to the wedding, more likely she won’t. She will be confused, disoriented, upset by the crowd, G-d knows she’ll have enough to deal with starting out in a new place.

She has to try her luck. For herself, and also for Oma, to know how far she’s helped, if Oma can move on.

“Hello, Reina,” Oma says, when she opens her eyes.

“Elisheva.”

“Yes, yes.”

She shows her to the trunk.

“I’m getting married next week.”

“You are? Danke G-tt.”

Ellie imagines the veil, washed and gleaming white, delicate lace, fashioned over her on her wedding day.

She opens the trunk. A fine layer of dust. Oma hasn’t touched it, hasn’t reached for it, not once, since last week.

“Oma, maybe you can let me have the veil for my wedding?”

The room is still. Dust motes float in the light between them.

The old woman looks down at the veil, at Ellie, and slowly, she nods.

(Originally featured in Calligraphy, Issue 830)

Oops! We could not locate your form.