Three Men with a Wildes Streak

The talents and accomplishments of celebrated immigration attorney Leon Wildes and his two sons, Michael and Mark, aren’t limited to the legal profession. In a fascinating conversation, the Wildes family opens a window to their true family business: helping other Jews.

5

15 Madison Avenue is one of those distinguished older high rises on Manhattan’s East Side where uniformed guards sign in everyone visiting its well-heeled occupants. The lobby impresses with its gleaming marble floors and walls baroque coffered ceilings painted in gilt and autumnal colors and a long bank of ornately sculpted brass elevators. A hushed ride in the walnut-paneled cars leads to the sixth floor home to Wildes & Weinberg specialists in immigration law.

Some people are blessed with the good fortune to get in on the ground floor of a growth business and Mr. Leon Wildes Esq. is one of them. When he decided as a newly minted lawyer in the late 1950s to specialize in immigration law he had no idea that the potential clientele would one day burgeon into the millions and that immigration would turn into one of the nation’s hottest political issues. Wildes & Weinberg founded in 1960 has grown into one of the country’s premier immigration firms. Its successes have enabled Leon Wildes to use his time talents and resources to help the Jewish community in significant ways. Today he works with his two accomplished sons who assist in carrying out their father’s legacy of law and service to the community.

It’s a huge office. As the secretary takes coats and leads us in we pass scores of cubicles and office doors housing a staff of close to fifty. Arriving in Michael Wildes’s spacious office we’re greeted by the family troika: Leon Wildes white haired and professorial-looking in rimless glasses and a lawyerly gray suit; older son Michael Wildes in his mid-forties a media-genic former mayor of Englewood NJ; and Mark Wildes the fair-haired lanky younger son who also went to law school then found his calling as a dedicated kiruv rabbi.

Each man has distinguished himself in his own way. But behind the Madison Avenue opulence of the office and the framed diplomas hanging on the walls lie three men who are in many ways simple ehrliche Yidden who desire nothing more than to do right by their community. And according to Mr. Wildes senior they are merely continuing to live according to the ways originally modeled to him by his father Mr. Harry Wildes z”l.

The Honest Jew from Bialystok

“My father originally came from Bialystok,” Leon Wildes tells us. “He spoke Russian, Polish, Ukrainian, Yiddish, English. My mother came from Scranton, though her family originally lived in Grodno.

“A rabbi from the Bialystoker shul on the Lower East Side, who had worked for a time in Scranton, suggested the shidduch to my father, and got him an invitation there for a Yom Tov. My mother was one of several sisters,” he adds with a twinkle, “but they conveniently made the other sisters disappear before they introduced my father to my mother!”

Harry, the new son-in-law, received the same help from the family as the other sons-in-law, being set up with a dry goods store in the area. In their case, it was in the little town of Olyphant five miles north. “I was the only Jew in a class of 100,” Leon remembers. “In our shul, we had twelve people for the minyan. But on Shabbos, the neighboring towns, Dickson and Throop, were short a couple of men. My older brother and I would walk a couple of miles to the next town, and my brother would lein for them. They used to pay him $2.50 for leining, but my father insisted he give me 25 cents of it, for listening and correcting his errors. Our father was adamant that the money was not a compensation for going to shul!”

Mr. Wildes describes his father as a member of that increasingly rare and endangered species, an old-fashioned Jew of impeccable integrity. For close to fifty years, he served as secretary-treasurer of their little shul, distributing the aliyos and taking charge of the hachnasas orchim. “He had a special calligraphy pen, and he used to take notes in a beautiful hand,” Leon recalls.

“Look at this,” Michael puts in, springing up and bringing over an ancient little metal box, riffling the fraying index cards inside. “We kept my grandfather’s file of the shul dues and aliyos. It used to cost twelve dollars a year to be a member.”

“Rabbis would come in from New York to raise money for their yeshivos,” Leon continues. “My father would find a way to keep them in the store until my brother and I came home from school. Then he’d make them give us a dvar Torah and learn with us a little. After that, he’d drive the rabbi around to all the little towns in the region, and accompany him back to his bus.”

“My grandfather was a very special person in my life,” Rabbi Mark Wildes contributes thoughtfully. “He’d call us up, and ask how we were doing, and then he’d say, ‘What are you learning? What daf?’ It would turn into an instant farhehr — and he always knew the Gemara, whatever we were learning!”

Harry Wildes was the one to make shalom when the local kids would tell Leon and his brother, “You can’t ride my bike; no Jews allowed on it.” At the same time, he insisted his sons never disturb their neighbors’ Sabbath repose on Sundays. In the kind of story that recalls legends about “Honest Abe” Lincoln, Leon recounts that he once received a call from a colleague, a religious Jew who was dean of a law school in Cleveland, asking for his help arranging citizenship for his foreign-born grandchildren. “I called another lawyer friend in Cleveland, who told me, ‘Don’t waste your time, they’ve tried everything.’ But I thought, why not try calling the district director of immigration? It was worth a shot.

“So I called the Cleveland office, and they told me the director was being replaced. ‘How about the deputy for citizenship?’ I asked. They said, ‘He’s on leave.’ I said, ‘So who’s minding the store?’ They told me it was the deportation officer, and put my call through to him.

“He answered, ‘Inspector Kowalchik,’ and I couldn’t help but ask, ‘In my home town, the Kowalchiks owned a store.’ I began saying, ‘They sold’ — whereupon the inspector interrupted me, and finished my sentence with, ‘Furniture.’ I said, ‘Are you from Olyphant?’

Serendipity had led Leon to a non-Jewish landsman. “He told me he did deportations, not naturalizations,” he says, “but I urged him to inquire, and try to do the right thing for the guy from his hometown. Then when he called back, a week later, the first thing he said to me was: ‘Who is Harry Wildes?’”

Suddenly Leon Wildes, the composed, articulate lawyer, can no longer speak. “My father,” he begins. then he chokes with emotion. Tears begin spilling out of his eyes, and Michael runs over to put a comforting hand on his father’s shoulder. Leon continues over the lump in his throat, “He called my father — the honest Jew.…”

After a moment he regains his composure, is ready to go on: “Inspector Kowalchik had called his mother in Olyphant. She was already in her nineties, but she clearly remembered how she had once bought a house dress from my father. It cost $2.98, and she gave him a twenty dollar bill, but he gave her change for a ten. That evening, realizing his mistake, he drove all the way back to her house — it was a good half hour’s drive — just to be sure she got the right change back that same day.”

The Small Town Boy Heads Out

Like his cousins, Leon’s older brother — who eventually became a doctor — was sent off to college at St. Thomas Aquinas, a Jesuit school chosen largely because it was tolerant of Jewish students’ needs to observe Shabbos and Yom Tov. When Leon’s turn came, he says, “I was all set to go.” But an uncle in New York urged his father to send young Leon to Yeshiva University in New York. “What, you’re gonna send the other kid to golochim dorten?” the uncle scolded.

Harry Wildes responded, “But my sons aren’t yeshivah bochurim. They’ll need a parnassah in life.” The uncle assured him that Leon would receive both a yeshivah education and professional studies at the same time.

The next obstacle was one that many parents can only dream of: Yeshiva University wanted to give Leon a free ride. But unlike ordinary parents, who would jump at such a chance, Harry Wildes refused to take it. “He wouldn’t take money from a Jewish institution,” Leon remembers. “He stomped out of the bursar’s office! And it wasn’t like he was a wealthy man who could have easily absorbed the cost.”

“I think my father gave back to YU much more than they gave him,” Michael Wildes points out proudly. His father has been teaching immigration law at YU’s Benjamin Cardozo School of Law for the past thirty-one years.

Suitcase in hand, the young Leon Wildes arrived in the big city with no family or connections nearby. He managed to succeed brilliantly anyway; when it came time to choose a law school, he opted to take advantage of a full scholarship at NYU (here there was no conflict with accepting money from a religious institution) rather than go to Harvard (which only offered a partial scholarship). “I think I chose to specialize in immigration law because I like to help people,” he now says, “and that’s still the essence of what I do.”

His first job out of law school was with HIAS, the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society. He left after a year, but retained a connection to them, hoping to one day serve on its board of directors. (That was a dream that came true; today, after many years of service, he continues to attend board meetings.) In 1960, he started his own practice, specializing in helping people faced with deportation or exclusion proceedings, or who had lost their citizenship (today the firm services corporate clients as well as individuals). Leon would eventually serve as national president of the American Immigration Lawyers Association and garner prestigious professional awards.

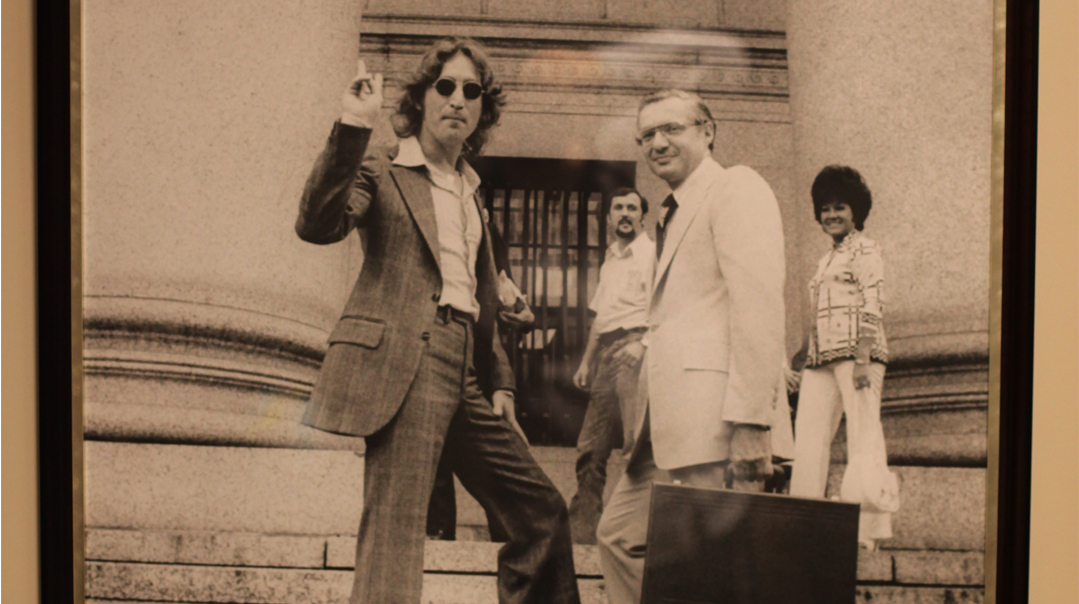

The legal landscape in immigration was vastly different in the 1960s and 70s. “Back then, there were maybe three or four hundred immigration lawyers in the entire country,” Leon says. “Today you have some 14,000.” His “big break” into legal fame came one fine day in 1972 when an old law school classmate suggested he take on a residency case for a music star. Not very familiar with rock and roll — Wildes’s tastes rather ran to the classical — he came home and told his wife, Ruth, that he’d met with Jack Lemmon and Yoko Moto. (Ruth, on the other hand, understood immediately that he was referring to John Lennon and his wife Yoko Ono.) Lennon was seeking a legal way to stay in New York with his wife. The case dragged on for five years and four court appearances, but resulted in an unexpected victory the day Lennon’s wife went into labor with their son. (It was also Lennon’s birthday; in celebration, Leon out and bought him a fancy passport case at Mark Cross.)

“A lot of legal chiddushim were created by that case,” Wildes says. “Every year, I give a lecture at Cardozo about it.” While he’s also written many articles for legal journals on the technicalities of the case, he’s currently working on a popular book about his experiences. “My father met Yoko for a cup of tea last week; she has offered to help him promote the book,” Michael mentions. “She was very close to my mother, who was very supportive when Yoko, already in her forties, was hoping to have a child.”

Michael puts this entertainment world glitz into perspective by quoting Rabbi Jonathan Rosenblatt of the Riverdale Jewish Center, who spoke a few weeks ago at the annual lecture the family sponsors for the yahrtzeit of Ruth Wildes, a”h: “Rabbi Rosenblatt said that people generally see it as a zchus for my father, that he became close to a famous music star,” he says. “But he said we should really see it in reverse: it was Lennon who had the zchus, that he should be able to get close to such an erlicher Yid!” While Leon admits that Lennon was “not my usual sort of friend,” he remembers him with a smile as “a wonderful guy.”

Leon Wildes with celebrity client, John Lennon

Signatures of Salvation

Lennon’s celebrity rubbed off on his legal counselor. Since then, Wildes & Weinberg has seen scores of celebrity clients, whose photos adorn the walls of Michael’s office: soccer star Pele, singer Sarah Brightman, designer Paloma Picasso, race car driver Dario Franchitti. The firm also defended Canadian basketball player Kwame James, who had been refused permission to remain in the US because his visa had expired. (James attained hero status when he subdued “shoe bomber” Richard Reid on American Airlines Flight 93, thereby sparing the lives of 197 crew and passengers.)

There are politicians on the wall too; one photo, in black and white, shows New Jersey Senator Frank Lautenberg and Connecticut Senator Joe Lieberman in front of the little succah the law firm used to put up on a balcony (they’ve since changed floors, and lost the balcony access — now they have to go out to eat). “That was terrific!” Michael says with a laugh. “Lautenberg said, “If we’re here in a succah, maybe I should be using my Jewish name — it’s Feivel.’ So Lieberman answered, ‘Okay, and my Jewish name is Yossi.’ Then the two of them started talking away in Yiddish — it was really something to see!”

Helping people from all walks of life has gained Wildes & Weinberg status and paid the bills. But from a Jewish point of view, Leon Wildes’ biggest contribution to immigration has been his efforts aiding HIAS to bring young Jews from Iran, Yemen, Syria, and Ethiopia into the country. “We had a lot of Iranian boys in the 1970s who needed to come into the country,” he relates. “I had a friend in the State Department, and he told me we couldn’t do student visas for them, because they weren’t planning to return home. There were 300 of them, and they needed affidavits of support. In the end, I made the decision to sign all the affidavits myself.”

He willingly admits, “I was scared stiff to do it! But I spoke to my rabbi, and he told me, ‘You have to feel strong about it. And make sure the boys get put in yeshivos where they won’t get lost.’”

Rabbi Moshe Sherer, ztz”l, of Agudath Israel helped place the boys into yeshivos all over the US. Yeshivas Ner Israel alone took about forty of them (foreseeing the need to create a future community, they also brought in forty Iranian girls). One can only imagine the nachas, and zchus, Wildes has in knowing that literally hundreds of Torah-true Sephardic families are thriving in America today because of his efforts. Michael mentions that his parents were major supporters of HIAS, and Leon says that although today most of the cases they handle aren’t Jewish, “I still keep a hand in, in case Jews need them again. I still send them interns.”

Michael Wildes, acting on behalf of the firm, took action just this year when Mrs. Frumet Teitelbaum was hassled by the INS on her entry to the US this past spring. Mrs. Teitelbaum’s husband, Rav Leibish, had been sent as a mashgiach to check mushrooms in India in 2008. No sooner had he put down his suitcase at the Chabad House in Mumbai, Gemara still in hand, when he was massacred by the terrorists who killed Gavriel and Rivka Holtzberg and six others. Mrs. Teitelbaum, who is Israeli but has eight children living in the US (her husband, a son of the Volover Rebbe and descendent of the Satmar Rebbe, was an American citizen), had been traveling frequently back and forth. Erev Pesach, an overzealous customs officer decided she’d been overusing her visa and refused to let her in, reducing the poor almana to tears. Fortunately, Michael Wildes ran to sort out the situation, making appearances on television and other media to put pressure on the INS to desist (which they did, acknowledging they’d overstepped their limits).

Number One Son

Both Michael and Mark attended Yeshiva University and its law school; in fact, Michael met his wife, Amy, while both were taking his father’s class on immigration law (Amy Messer Wildes today works in the firm’s branch office in Englewood, New Jersey, and takes care of the couple’s four children). But Michael says his career in public service really began at age fourteen, “when I did my first tahara with the chevra kadisha,” he says. “I’m an ish sadeh,” he jokes. “I’m a person who has to be out there, doing things. I was an auxiliary police officer; I work with Hatzolah; it’s just a fundamental part of my nature.

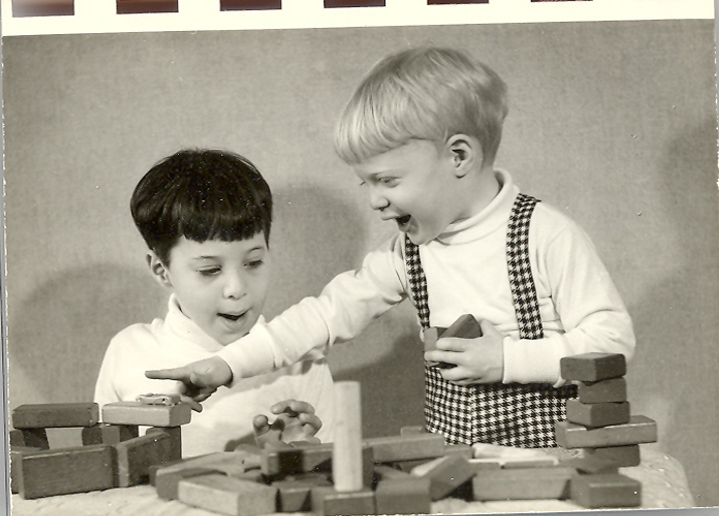

“I used to go to law school during the summers, and work with my father at the office during the year,” he says (today he is managing partner in the firm). “My father is in this building forty years; my brother and I used to come in with our father when we were little.”

“Yeah, our mother used to pack us those tuna sandwiches in foil,” Mark remembers with a smile. “And if we behaved, we’d get a reward — she’d buy us a book.”

But Michael didn’t join his father’s firm immediately; desiring to gain public service experience, he worked as a federal prosecutor with the US Attorney’s Office in Brooklyn, beginning in 1989. “Sometimes my father and I would be on opposite sides of a case,” he says. “He’d be working to keep somebody in the country, and I’d be working to kick them out!”

But in 1993 he “saw the light” and joined his father’s firm. He declares, “It’s the greatest zchus to be able to work with my dad, to stand up when he enters a room or kiss him or go out to shop or get a sandwich together. Those are the most enduring experiences.”

Michael has spent many pro bono hours trying to keep the Jewish community alert to the possible dangers of playing fast and loose with the INS. “I try very hard to help keep religious organizations out of trouble,” he says. “Rabbis and shuls can make a chillul Hashem when they cross legal lines trying to ‘help’ people. You have to keep in mind, dina malchusa dina. Today, the INS will check up on fake marriages; they’ll even show up on Shabbos and Yom Tov to make sure you’re really there with your spouse.

“Sometimes Jews from other countries come here and become more religious, but we have to be sure to find them jobs, ways to help them stay. If they can’t remain in a Jewish environment, and have to return to a little village in Uzbekistan or somewhere, all their gains on a Jewish level will be lost.”

Michael just recently stepped down from his second term as nayor of Englewood, New Jersey. “I was sworn in four times, twice as city councilman and twice as mayor, on four Chumashim owned by four different grandparents,” he boasts. There he presided over a community of some 30,000 people, a motley mix of affluent Jews and communities of Latinos and African Americans. His brother Mark offers, “I’m really impressed the way my brother brought such different communities together, people from such different worlds. Even the local pastors would stop by his succah.”

“Yeah, one of them was so moved when he saw our father blessing his grandsons on Succos that he started crying,” Michael says. “He told me, ‘We [non-Jews] need a Shabbos!’”

But not all his constituents were so pro-Jewish. “There were yeshivah boys who would get beaten up in the rougher neighborhoods,” Michael says. “I’d go pick up the yarmulkes and visit them in the hospital. Then I’d make the kids go to their school and give a dvar Torah about Martin Luther King. I’d also hold meetings where people could ask their questions. One lady asked me, ‘What about those fringes Jews wear? I heard the more fringes you have, the richer you are!’

“A different woman was sure the Jews were responsible when a McDonald’s burned down, because her mother told her so. I asked her, ‘Did you ever meet a Jew?’ She said no, so I told her, ‘Well, I’m one.’ Michael’s duties often involved visiting the victims of local disasters like fires or attending local functions, and when these occurred on Shabbos, he often walked for miles to put in an appearance, wearing out “several pairs of Florsheims.”

Englewood also happens to be the home of a mansion owned by the Libyan government, not-so-conveniently located next to Moriah, a Jewish day school, as well as the home of Rabbi Shmuley Boteach. When Muammar Gaddafi came to the US for the annual United Nations Conference a year ago, his government began refurbishing the house, which had sat unfinished for thirty years, in preparation for his stay [this after New York City refused to let him pitch a tent in Central Park]. But Michael was having none of it: “There was no way I was going to put out a red carpet, or pitch a white tent, for the man who was behind the terrorist bombing in Lockerbie that killed 200 people, of which thirty-eight were New Jersey residents,” he says indignantly. He organized a demonstration, and filed a lawsuit in State Superior Court to halt work on the property (which, as diplomatic property, had not paid any city taxes for thirty years).

Michael has, in fact, become known as an expert on security, and has met with several Homeland Security directors. He’s scheduled to spend this week in London meeting with Jewish community leaders to discuss security for synagogues and individuals in the UK. “The borders everywhere have become very porous,” he warns. “We don’t have an adequate departure system, and containers are not adequately policed. There are too many blind spots in airports, and not enough proactive work.”

That said, he isn’t anti-immigration; he simply feels the policy needs to be reformed. “We need a point system, like Australia or Canada,” he suggests. “And we need to encourage bilingual, university-educated people to come here.” His father has also stated that legalizing aliens and being able to collect their tax revenues makes the most sense, both economically and morally. Himself the son of an immigrant, Leon told a reporter for Super Lawyers magazine, “In college I studied the Bible. And in the Bible, in some thirty-four instances, probably the most repeated mandate is, ‘Love the stranger’ … I have found that a kind of byword in my professional life.”

It’s no secret that Michael Wildes has further political ambitions; he’s already set up a Wildes for Congress Fund — “tzeidah l’derech,” he quips, “for when the time will be ripe.” The Democratic Leadership Council listed him as one of the “One Hundred to Watch,” anticipating him as a rising star. It sounds like we’ll be hearing from Michael for a long time to come.

The Second Son

Mark Wildes has been mostly listening quietly as we talk. But when we turn our attention to him, the once-still waters reveal their depth. Trained as a lawyer like his father and brother, circumstances nevertheless pointed him into a different kind of community service: attracting unaffiliated Jewish young people back into the Orthodox world.

While Michael’s career largely picks up from his father’s lead, Mark’s career might more accurately be said to follow his mother. Ruth Wildes, a warm and gracious hostess and eishes chayil who was deeply loved by her family, passed away in 1995, but her family has never forgotten the Shabbos and Yom Tov tables she would make for them. “In our family, Shabbos started on Tuesday,” Mark smiles. “My mother was a yekkeh, very much ‘k’das k’din,’ but she always managed to be flexible to accommodate any number of unexpected guests — and there was always enough food. She went way beyond what was required, whether it was for Shabbos or shalach manos, and did it all with such tremendous zeal and belief.”

While finishing his smicha at Yeshiva University, Mark accepted a rabbinic internship at the Queens Jewish Center. There he often met young people and would “schlep them home to my family, who lived not far away.”

“There used to be this whole conspiracy between our mother and the shul’s rebbetzin when a new single person showed up,” Michael grins. “The two of them were like a well-oiled machine with their own brand of sign language. They’d point to the newcomer, then to us, to ask, ‘Is he single?’ Then there would be more gestures and a show of fingers to tell us, ‘Yes, he needs a place for Shabbos, yes, him and two others!’

When the family began hosting large yahrtzeit lectures in Ruth’s memory, featuring such noted speakers as Rabbi Norman Lamm and Rabbi Shlomo Riskin, they hoped to organize a more ongoing community service program in her honor. In 1998, therefore, with the support of his family, Mark launched the “Manhattan Jewish Experience.” This is an organization whose essence is, in Mark’s words, “a way of continuing my mother’s Shabbos table.”

MJE, whose goal is kiruv among Manhattan’s young people, soon grew into a quite a large Shabbos table. After twelve years of growth, it now has locations on the East Side, the West Side, and lower Manhattan, with a two million dollar budget and anywhere between 80–150 people hosted for Shabbos every week. Under Mark’s leadership, the organization supports a full-time staff of twelve, including five rabbis, all working furiously to draw young Jews in their twenties and thirties away from intermarriage and towards a closer connection to Torah Judaism. As explained in their glossy brochure, MJE offers not only Shabbos/Yom Tov services and meals, but classes attended by close to 300 people weekly in Judaism, Hebrew, and one-on-one learning.

Rabbi Mark himself gives regular shiurim, in addition to coordinating MJE’s programs. Some of those shiurim take place in the conference rooms of professional offices, including Wildes & Weinberg. He also organizes, with the help of his staff, guest speakers, weekend and summer trips, and shidduch-oriented get-togethers. (So far,” Mark says proudly, “we’ve made eighty matches.”)

Mark says there are some 150,000 unaffiliated Jewish singles in the New York area, many of them lonely. “New York can be a cold, unfeeling place for many people,” Mark points out compassionately. “The work environments are often cutthroat, the social scene can be tough, and we provide a warmth that contrasts sharply with that.

“There’s a lot of kiruv organizations out there. We play the game — we run the slick ads to attract people in — but the bottom line is the warmth, the Shabbosim. We make it a point to know everyone’s name. The truth is, people recognize true warmth when they see it, and they respond to it.

“Rabbi Riskin used to say, ‘For the price of a chicken, you can save a Jew’ … When it all comes down to it, it’s the cholent and the warmth that sell Judaism.”

Although he’s a father of four, Mark looks like he could be one of the twenty- and thirty something young people he reaches out to. His wife, Jill, is herself a baalas teshuvah originally from Great Neck. “Half of my wife’s friends intermarried,” he says. “A lot of our effort goes into simply trying to make sure young Jewish men and women marry each other — even if they don’t become more religious, it buys time for the next generation.”

The kiruv scene, like the immigration scene, has changed much in the past thirty years. While baalei teshuvah from the 1970’s and 80’s tended to be spiritual seekers, thirsting for meaning and spirituality, many of today’s unconnected Jews are simply looking for a way to be happier. “It’s unbelievable — it seems like this is the unhappiest generation,” Mark observes. “Go into a Barnes and Noble, and the biggest section is the self-help books — how to get happy. Every year they publish thousands of books about it. This generation, more than previous ones, so often comes from broken homes. The young people often lack models of what happy family life is all about … happiness comes when you have a tachlis in life, but first we have to bring them in before we can show them that.

Mark has recruited congenial shomer Shabbos families to help serve as hosts to his Jewish singles, and tries to keep new baalei teshuvah connected to established community members for “maintenance” and guidance. “We help maybe fifteen people become baalei teshuvah a year,” Mark says. “They become our stars. And even if their friends and family don’t follow, at least it heightens their awareness, and maybe they’ll take on something they didn’t do before. I’m finding that many of the third-generation Russian Jews are very receptive to us; they’re smart and successful, and now they’re looking for something meaningful.

“I feel very lucky,” he continues. “My brother is my best recruiter. My family supports me on every level.” His wife helps out as well; even the kids participate. Brother Michael comments, “It’s in our DNA to be doing this kind of thing.”

Onwards and Upwards

The Wildes men have to move along to a meeting — these are three very busy people — so we wrap up our discussion. As we leave these tasteful offices, it’s touching to realize that beneath the elegant facades, beneath the well-tailored suits, are three men who are, in their essence, a deeply connected family with very sincere Jewish hearts. In the end, they’re still very much the son and grandsons of a poor immigrant from Bialystok who knew his ultimate legacy to his descendents would be not his fortune, but his Jewish sense of ahavas Yisrael, ahavas Torah, and flawless integrity.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 338)

Oops! We could not locate your form.