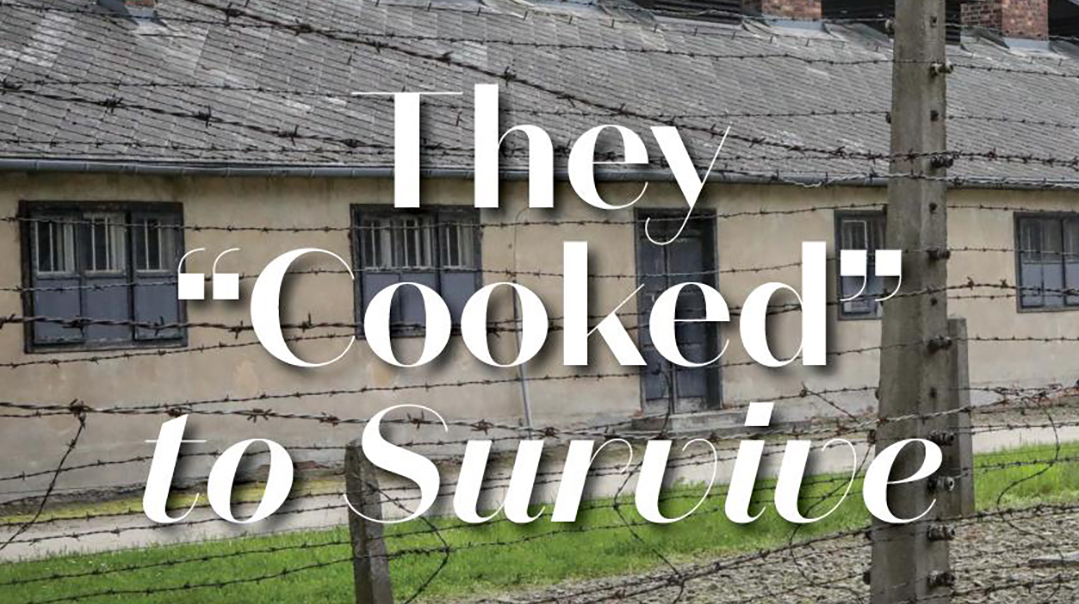

They Cooked to Survive

| July 22, 2020

The recipes in this book are almost placeholders, scattered among the history lessons and riveting anecdotes of the Sternberg family’s life.

The title Recipes from Auschwitz sounds oxymoronic. While suffering starvation, deprivation, and torture in concentration camps, could anyone actually cook? Perhaps because of that, I was motivated to read Dr. Alex Sternberg’s recently released book and find out for myself what it was all about. Did the inmates have food to cook in Auschwitz? Could they have carved a moment in the day while struggling to fill their work quotas, find a few crumbs of bread, and avoid beatings to prepare recipes?

The answer is obviously a resounding no. And yet, here it is — a collection of several dozen recipes, memorized by a young woman in the concentration camps and written down in detail after the war. Part cookbook, part history book, Recipes from Auschwitz gives a detailed account of Hungarian Jewry for two millennia, following the lives of the Sternberg family and interspersed with Hungarian recipes during the long, dark nights in Auschwitz.

I set up an interview with Dr. Sternberg and spent a fascinating hour hearing bits and pieces of his eclectic life. A fluent Yiddish-speaker born in Hungary, Dr. Sternberg lived in Vienna for a year before emigrating to Boro Park as a young teen. He attended Mesivta Torah Vodaath and an all-black karate school simultaneously, becoming one of America’s top ten karate champions while practicing pediatric pulmonary medicine. But why did he write this particular book? And what did he want readers to gain from it?

Bridging Two Worlds

Alex’s parents, Marton Sternberg and Olga Elek, came from small villages in Hungary. Marton was the youngest of five children, and grew up poor and fatherless (his father died of a heart attack when Marton was an infant) in the chassidish community in Bodrogkeresztúr (or more commonly, Kerestir, home of Reb Shayele of Kerestir). His mother and older brothers raised him, and he was heavily influenced by the chassidim and rebbes of his hometown, who showed him special attention.

Olga’s father was a banker, and her family practiced the ultra-liberal Neolog Judaism. She attended a Christian high school and secular college, and had plans to become a doctor before Jewish quotas and anti-Semitic laws made continuing in university impossible. The marriage of these two vastly different individuals may seem extraordinary, but such were the times following the war, as survivors rebuilt their lives after experiencing unfathomable losses.

Aside from their religious differences, Marton and Olga’s personalities and outlooks on life were vastly different. Marton returned to Hungary after he was liberated from Bergen-Belsen to look for surviving family members. He found no living souls from his family — his parents, siblings, young wife, and infant son had all been murdered by the Nazis. Even the Jewish cemetery where his father was buried was no longer — locals told him it had been plowed over to plant a cornfield. Although he remarried and lived in Hungary for over a decade after the war, once he was able to leave with his new family, he never returned to his country of birth.

Olga had been a socialite as a girl, but always with a sense of modesty guiding her actions. Although the humiliations she experienced during the war affected her deeply, she did not become despondent. “My mother was an exceptionally optimistic person,” says Dr. Sternberg.

She showed incredible resilience and strength during and after the war, and made a complete religious turnaround in marrying Marton — keeping a strictly kosher home and observing mitzvos for the rest of her life. Both Marton and Olga lived into their 90s. Olga passed away on the eve of the birth of her youngest grandson in 2004, and Marton passed away a year later at the age of 99.

Honoring a Promise

“The book fulfills a promise I made to my mother,” shares Dr. Sternberg. “She’d ask me repeatedly to publish her stories, and just to make her happy, I’d tell her, ‘Okay, okay, I’ll write it!’” But it wasn’t until the extended Sternberg family celebrated his mother’s yahrtzeit with a Zoom meeting, for which they’d all cooked several of his mother’s recipes, that Alex realized the value of his book in perpetuating his parents’ story.

“One of my mother’s favorite stories was how she and the other ladies would spend their time ‘cooking’ to survive the daily deprivation, humiliation, and hunger,” he says. The women would take turns describing how they had prepared their favorite dishes before the war — going into great detail about each recipe, describing the fine linens and china they would use to set the beautiful tables, and listing all the family members who would enjoy their meals.

Tragically, most of these women never saw their family members again. But during those bitter, hungry nights, these detailed “banquets” kept their spirits going and gave them hope for the future. For Alex’s mother, Olga, it was more. She hadn’t been much of a cook before the war. Afterwards, remembering all she had learned from the other women in her barracks, she wrote down all the recipes and used them to cook for her own family once she was married.

A Study of Hungarian Jewish History

But the recipes in this book are not the bulk of the content — they’re almost placeholders, scattered among the history lessons and riveting anecdotes of the Sternberg family’s life. “There’s another reason I wanted to write this book,” explains Dr. Sternberg. “Most of the literature on the Holocaust describes the Polish, Russian, or German experience. There’s not much about the Hungarians. I wanted to bring the Hungarian Jewish experience to the reader.”

The early chapters of his book provide a fascinating and detailed look at Hungarian Jewry through several millennia, written in a light and easy-to-read manner, yet clearly illustrating a wealth of research. Dr. Sternberg traveled to Hungary multiple times to follow up on leads, clarify details, and gather historical information to paint an accurate and thorough portrait of the Jews in Hungary dating back to their earliest mention, following the Bar Kochba revolt.

More than a Cookbook; More than Jewish History

Today, most of us prepare food in kitchens stocked with incredible varieties of produce, as well as almost unlimited quantities of eggs, poultry, meat, dairy, grains, spices, and herbs. Some of us stave away tediousness and boredom by attempting complicated recipes. Those less inclined to spend extra hours in the kitchen simply aim for feeding all the picky members of their families without any meltdowns or hunger strikes.

This book, written around a central theme of “cooking” in Auschwitz, creates a paradigm shift for those of us who are so blessed, we don’t even see it. We temporarily step out of our lives and into the past, and when we return, the message is clear — we are privileged to have access to so many ingredients and to be able to cook for our families. Even deeper than that is a reminder of our priorities — that with all the novel and trendy foods popular today, nothing is as meaningful as recreating the traditional recipes of our ancestors.

The women of the past kept it real. They mastered the art of “clean eating” — growing their own food, making do with what was available, using almost no processed foods, and creating mouth-watering meals their children remembered fondly and passed down to their own children.

When we chop vegetables for soup, soak beans for cholent, and roll out dough for bilkelach, we are fulfilling the dreams and desires of those women — to feed and nurture their families once again.

It’s incredible to think that during the most horrifying of times, these women in Auschwitz let themselves reminisce about meals of the past, and even more incredibly, hoped and planned for the future in great detail. It is a priceless gift to have these recipes, recorded by Olga herself and published by her son, and to be able to recreate them today for our families.

Olga’s Paprikas Csirke (Chicken Paprikash)

MEAT

SERVES 6

- 2–3 Tbsp cooking oil

- 1 large Spanish onion, diced

- 1⁄2 green or red bell pepper, diced

- 1 tsp Hungarian sweet paprika

- pinch pepper

- 1 tsp salt

- 5–6 parsley stalks

- 1⁄2 tsp soup mix

- 8 chicken legs, skinned if desired

In a large skillet, heat the oil and sauté the onions over medium heat. When the onions glaze, add in the peppers, and continue to cook until soft. Stir in the paprika, pepper, salt, parsley, and soup mix.

Add the chicken legs to the skillet, rolling them in the sautéed mixture to coat. Add enough water to cover the chicken legs. Cover and cook over a medium flame for about 50 minutes. To reduce the amount of liquid, if desired, remove the cover after the first 30 minutes and simmer for the remaining 20 minutes. Serve hot.

Note from Olga: As vegetables cook slower, you must start that first. Once the vegetables soften, you can add the chicken, which cooks faster.

Olga’s Geztenye Rollad (Chestnut Roll)

MEATLESS

SERVES 8 FOR THE ROLL:

- 2 lbs chestnuts, boiled and peeled

- 2 Tbsp confectioners’ sugar

- 2 oz or shot glass of rum

- 2 Tbsp margarine (melted)

- 3 Tbsp non-dairy creamer

FOR THE CHOCOLATE CRÈME:

- 1 Tbsp margarine, melted

- 1 egg yolk

- 2 Tbsp confectioners’ sugar

- 1⁄2 cup black coffee

- 1 lb baking chocolate, melted

In a large bowl, crush the boiled and peeled chestnuts. Add sugar, rum, margarine, and non-dairy creamer. Mix thoroughly to make a moist paste. You will have to knead it with your hands. Transfer to parchment paper and shape into a thick roll. Set aside. In a large bowl, combine all the crème ingredients and mix until creamy and smooth.

Place the chestnut roll on top of moist cheesecloth and place another moist cheesecloth on the top (sandwich the roll between two cheese-cloths). Using a rolling pin, spread the chestnut roll between the cheese-cloths until flat, about 1 inch thick. If the roll is very brittle, add another tablespoon of non-dairy creamer. Remove the top cheesecloth and spread two-thirds of the chocolate crème onto the roll. Roll it up carefully and smear the remaining crème on top. Transfer to a dish. Place in the refrigerator until the roll becomes firm, about 1 hour. Slice into pieces like thick salami and serve.

(Originally featured in Family Table, Issue 702)

Oops! We could not locate your form.