The Nastiest Race Ever?

The country has seen some scurrilous campaigning before, arguably even worse than that of 2016, replete with accusations of personal immorality, criminal conduct, incompetence, and unfitness. In each case, the nation and the democratic process survived

I

n these days after the election, America is still reeling from one of the most bizarre and ferocious campaigns in presidential history. Who can remember such mudslinging? Even if some of it was truth-slinging, it has been, to say the least, a dismaying experience.

However, the country has seen some scurrilous campaigning before, arguably even worse than that of 2016, replete with accusations of personal immorality, criminal conduct, incompetence, and unfitness. In each case, the nation and the democratic process survived. There is reason to believe that they will this time too.

Character Assassination

Americans invented the attack ad, but they didn’t invent mudslinging. The credit for that goes to the ancient Romans who were known to advise: Fortiter calumniare, aliquid adhaerebit, “Throw plenty of dirt, and some of it will be sure to stick.”

The term mudslinging came into use only after the Civil War, but the practice was as old as the republic. George Washington was branded a “hypocrite” and “imposter”; Andrew Jackson accused of bigamy; Franklin Roosevelt of being mentally deranged. We’ve chosen here two of the more interesting and significant splatterings, and how the targets responded:

Abraham Lincoln: The Black Republican

As much as Abraham Lincoln is revered today, he was often reviled in his own lifetime. His unyielding opposition to the expansion of slavery brought upon him the hatred and calumny of the Southerners and their Northern allies. In the 1860 campaign, Lincoln was assailed as a “Black Republican” who would abolish slavery and impose legal and social equality on the races. In a typical cartoon of the day, Lincoln was depicted dancing arm-in-arm with a smiling black woman. The Charleston Mercury newspaper called him a “horrid-looking wretch… sooty and scoundrelly in aspect,” and he was burned in effigy in the South.

Even among his fellow Union leaders, sneers about his ungainly physical appearance found their way into circulation. Lincoln’s own top commander, General George B. McClellan, referred to him as a coward, “an idiot,” and “the original gorilla.”

Yet by the end of the Civil War, Lincoln had earned the respect, confidence, and even the love of his colleagues and the nation. Entire volumes have been written about how he did it, but briefly put, he won them over by the sheer force of his personality and an unswerving conviction in the imperishability of the Union and the worth of human beings.

Lincoln’s ability to rise above all personal and petty considerations was eloquently captured by Treasury Registrar Lucius Chittenden. Chittenden concluded that “Lincoln must move upon a higher plane and be influenced by loftier motives than any man” he had ever known.

When Lincoln died from an assassin’s bullet in 1865, Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, who had once ridiculed him as “that giraffe from Illinois,” wept openly in grief, as did millions of others.

John F. Kennedy: Overcoming Religious Prejudice

One hundred years after Lincoln’s time, the mudslinging was aimed at the candidate’s religion, rather than his politics — which were inoffensive —or his looks, which were as good as any movie star’s.

The disastrous defeat of Al Smith in 1928 so traumatized the Democratic Party that for decades afterward even its own Catholic leaders would not consider a Catholic for the presidential nomination. As Harry Truman recalled: “Al Smith was given the nomination, and that set off the most vicious anti-Catholic, anti-Jewish, anti-Negro movement that we have ever had in any political campaign… there was more slander and mudslinging going on than at any time I can remember.”

John F. Kennedy broke the unofficial ban in 1960. He chose to confront his accusers, denying their contention that if he entered the White House he would be taking orders from the Pope.

In the West Virginia primary, Kennedy conclusively demonstrated his vote-getting ability in an overwhelmingly Protestant state. At one point, JFK appeared in an ad in which, with hand on Bible, he solemnly declared it would be “a sin against G-d” for a president to put his religion above the Constitution.

West Virginia was a bitter fight, in which he defeated his chief rival, Minnesota senator Hubert Humphrey. Not all the whispering was against Kennedy, though. Humphrey was outraged at being accused of draft dodging by Kennedy campaigners. This was untrue; he had been rejected by the army in World War II for medical reasons.

There was some irony in all this. In the general election, the impact of Kennedy’s Catholicism was ambiguous. It probably helped him in the urban and industrial states but hurt him elsewhere. JFK remains the only Catholic to have been elected president.

And while Kennedy observed the outer forms of the religion he was born into, he was by no means religious. In private, he dismissed it as merely “one of the things I do for my father.” As president, he certainly did not take orders from the Pope or any other Catholic authority. However, some said he did take orders from the “Pop,” his controversial father, Joseph P. Kennedy, who masterminded the Kennedy campaign.

Kennedy had been belittled by Humphrey and others as a spoiled rich boy, but he proved tough enough to face down the Soviet bully Nikita Khrushchev in the Cuban Missile Crisis. He also made his fellow Americans a bit tougher by reinvigorating the President’s Council on Physical Fitness, even though he himself suffered from a carefully hidden case of Addison’s disease (another case of truth-slinging).

The assassin’s bullets that felled Kennedy on November 22, 1963, remain a traumatic moment for Americans, who accorded JFK an average 70% approval rating during his abbreviated term in office.

Fitness Test

As in 2016, the issue of fitness for office has been raised before in presidential campaigns. But as we will see, past performance has been an unreliable indicator of presidential timber.

Old Hickory, New Ideas

In 1828, the election of Andrew Jackson, another man with apparently little to recommend him for the presidency, had touched off a period of nationwide hand-wringing. Many regarded Jackson’s victory as the “triumph of the mob” and the end of the republic. As Inauguration Day approached, Daniel Webster, a senator from Massachusetts, wrote: “Gen. Jackson will be here about Feb. 15… Nobody knows what he will do when he does come… My fear is stronger than my hope.”

Jackson’s reputation as the hero of the Battle of New Orleans and vanquisher of Indians (a popular thing to be at the time) gave him instant name recognition as a presidential candidate. But not everyone was so enthralled with his battlefield exploits. Senator Henry Clay dismissed Jackson as “a mere military chieftain… I cannot believe that killing 2,500 Englishmen at New Orleans qualifies for the various difficult and complicated duties of the First Magistracy.” Clay wrote off Jackson as “ignorant, passionate, hypocritical, corrupt, and easily swayed by the basest men who surround him.”

As president, Andrew Jackson was far from being a puppet. Despite a lack of formal education (his literacy was a shaky proposition), he could translate the skills of military command into the political realm, and proved a shrewd handler of personalities.

In the White House, Jackson fought a different kind of war, this time for the average American against big money. He made good on promises of economic decentralization by dismantling the Second Bank of the United States, a powerful foe.

Jackson’s military background also gave him an advantage in putting down a threat of secession by South Carolina in a dispute over tariffs. When he threatened to send troops into the state to put down a secession, they knew he meant it and they backed down. It would serve as a precedent for Lincoln not many years later.

The Jacksonian era was not the end of the republic, as some had feared. Historians have hailed it as the beginning of a new era of democratic politics, in which the popular will found more direct expression than ever before. Until then, state legislatures chose electors who voted for president. In the new system, vigorously supported by Jackson, for the first time the people could vote directly for president.

America displayed its admiration for Jackson by having his face grace the front of the 20-dollar bill (since 1928), although his visage will soon be relegated to the back of the bill to make way for Harriet Tubman.

Overqualified and Underperforming

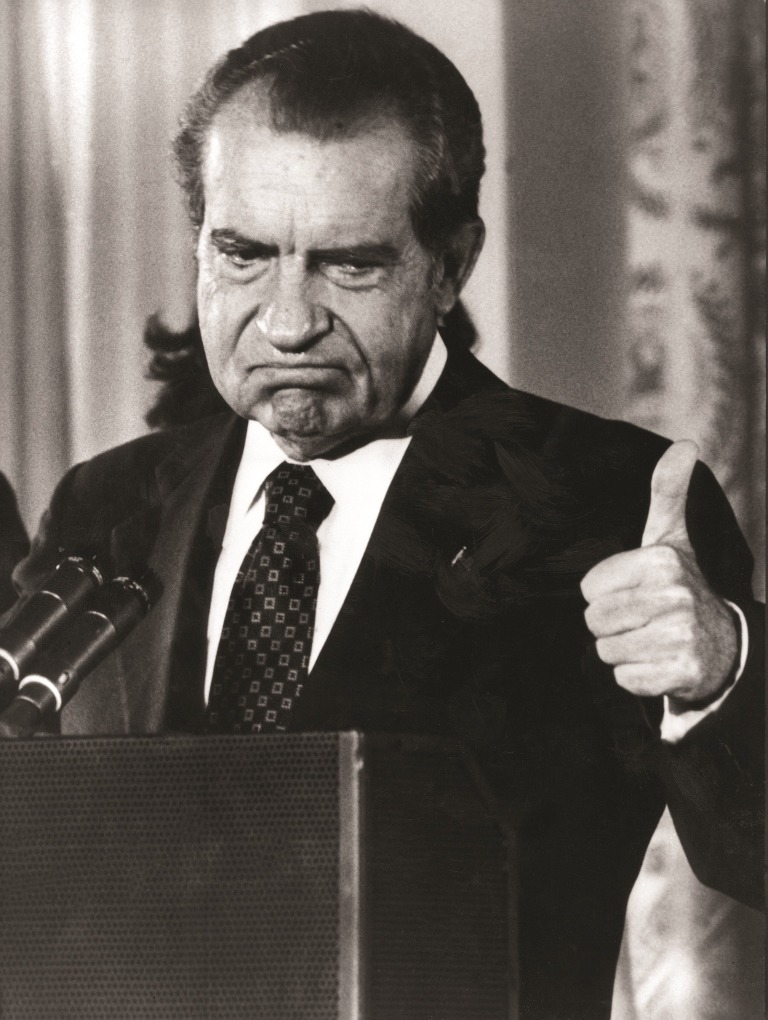

A great resume doesn’t always make for a great president. Richard Nixon and George “Papa” Bush were clearly the two most qualified men to serve in the Oval Office in the last half century.

Nixon was a lawyer and Navy lieutenant commander in World War II. He served in the House and Senate and as vice president for eight years. He lost one race for president and another for governor of California before finally capturing the big prize in 1968. Nixon did some good things. He extricated the US from the Vietnam War and brought a thaw to the Cold War by his visits to China and Russia. But Tricky Dicky’s paranoia and penchant for playing political dirty tricks against his enemies did him in. Not content with what turned out to be a 49-state win in his 1972 reelection campaign, Nixon had to resign in disgrace for obstructing justice in the burglary at Democratic Party Headquarters at the Watergate complex.

Papa Bush’s CV was even better than Nixon’s. A Navy pilot during World War II, he served in the US House of Representatives, was the United States ambassador to the UN, chief of the US Liaison office with China, and CIA director.

As president, he forced Iraq’s Saddam Hussein to beat a hasty retreat from Kuwait during the 1991 Gulf War, after which his approval rating peaked at 90%.

It didn’t last. Yesterday’s war turned into tomorrow’s recession and Bush was a one-term president when a little-known governor from Arkansas named Clinton beat him soundly in the 1992 election.

Rising Above the Fray

Politics is a grimy business, yet there have been presidents who have left office with their reputations intact.

George Washington: Fit for a King

Nobody slung mud at George Washington. Well, almost nobody. Thomas Paine once described Washington as a “creature of grossest adulation, a “hypocrite in public life,” an apostate and imposter. Paine’s sentiment had no effect on the general opinion. Washington was elected by the unanimous vote of the Electoral College — twice! No president since has enjoyed such a vote of confidence.

Cognizant that every decision they made would be precedent setting, Washington and the other Founders pondered every detail of governance and the trappings of authority. They sought a democratic style, but understood that titles and ceremonies were still needed to inspire respect.

One of the questions that arose was what to call the president. It was enough to test the humility of anyone, even the Father of His Country. Initially, he favored “His High Mightiness, the President of the United States and Protector of their Liberties.” Fortunately, he opted in the end for “Mr. President.”

Nevertheless, President Washington would appear in public in a horse-drawn coach, attended by servants in livery, and incongruously, to the music of “G-d Save the King.” To offset the possible monarchical effect, he made a point of going for a walk daily on his own two legs, showing himself to be just like any other American.

Even as a general Washington practiced consultatory leadership. He would make the final decisions and take responsibility, but only after hearing what others had to say. But there was never any doubt about his decisiveness. For example, in putting down the Whiskey Rebellion of 1792, Washington not only sent militias into Pennsylvania, he led them personally, the only time an incumbent president has commanded troops in the field!

Historians make careers of revising — usually downward — the reputations of famous figures. In Washington’s case, however, little has been written to change the initial assessment. As his 20th-century biographer Douglas Southall Freeman wrote, “the great big thing stamped across that man is character.“

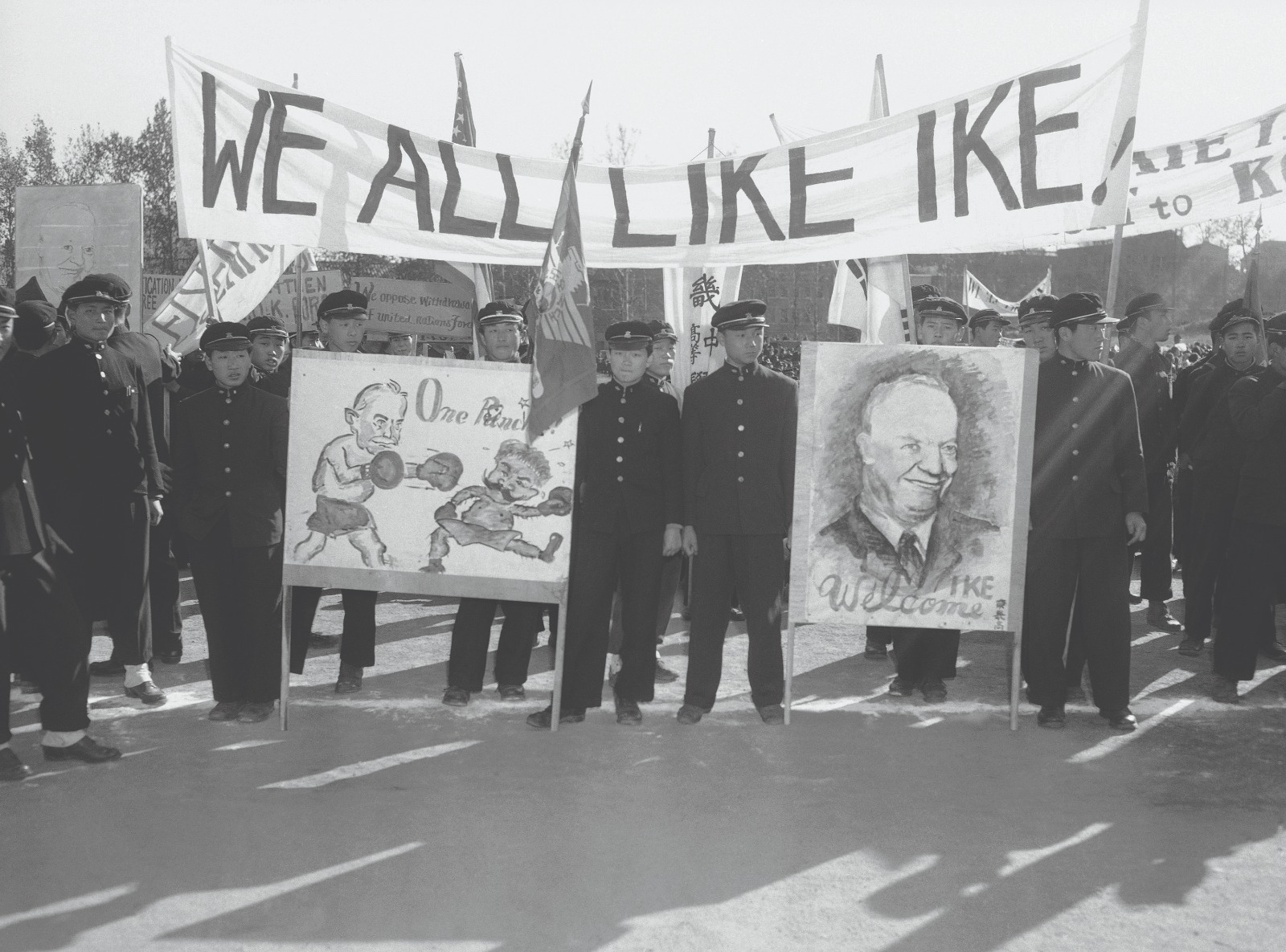

Dwight Eisenhower: Integrity First

Dwight D. Eisenhower, Supreme Commander of the Allied Forces in Europe, was a subtler case. Eisenhower, or Ike, as he came to be called, won landslide victories over Adlai Stevenson in 1952 and 1956, due chiefly to his war record. Prior to that, he had never held elective office. While he was not as adept at making the transition from war to politics as Jackson, he was not another Grant either.

He found the cut and thrust of political campaigning distasteful and sought to remain above it. As Eisenhower speechwriter and confidante Emmet John Hughes recounted a typical private outburst: “Let me tell you, nobody is going to talk me into making any idiotic promises about elect-me-and-I-will-cut-your-taxes- by-such-and-such-a-date. If it takes that kind of foolishness to get elected, let them find someone else for the job.”

Eisenhower’s essential honesty was dented during the Cold War. The most embarrassing moment of the administration was in 1960 when the U-2 reconnaissance flights over Soviet territory he had secretly authorized were exposed. Initially, the president tried lying, saying that the plane was merely a weather-research craft gone off course.

But when the Russians produced the pilot, who had safely parachuted to the ground, along with incriminating evidence — including an unused suicide kit in case of capture — the US was forced to admit the truth.

It was tough medicine to swallow for the man who once said: “I know only one method of operation. To be as honest with others as I am with myself.”

After the U2 fiasco, Khrushchev canceled their summit meeting, but Ike did not give up on his pursuit of world peace. Historian John Lewis Gaddis remarked: “Historians long ago abandoned the view that Eisenhower’s was a failed presidency… He did, after all, end the Korean War without getting into any others. He stabilized, and did not escalate, the Soviet-American rivalry. He strengthened European alliances while withdrawing support from European colonialism. He rescued the Republican Party from isolationism and McCarthyism. He maintained prosperity, balanced the budget, promoted technological innovation, facilitated (if reluctantly) the civil rights movement and warned, in the most memorable farewell address since Washington’s, of a ‘military-industrial complex’ that could endanger the nation’s liberties. Not until Reagan would another president leave office with so strong a sense of having accomplished what he set out to do.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 634)

Oops! We could not locate your form.