Shelter

When Honey is done, she closes the succah door securely behind her. Everything is just as it always was. Everything is perfect. Now the boys can arrive

As soon as Sol has the succah in place, near the rhododendron bushes at the end of the garden, Honey lugs out her paints.

“It’s still there, you know,” Sol informs her.

“It always needs touching up,” she returns.

He shrugs, that staid and solid husband of hers, and says, “Have it your way. Don’t stay up too late!”

Then he puts on the kettle and offers her a cup of tea, and she says, “That’s all right, thank you,” and her feet fly down into the little wooden shelter.

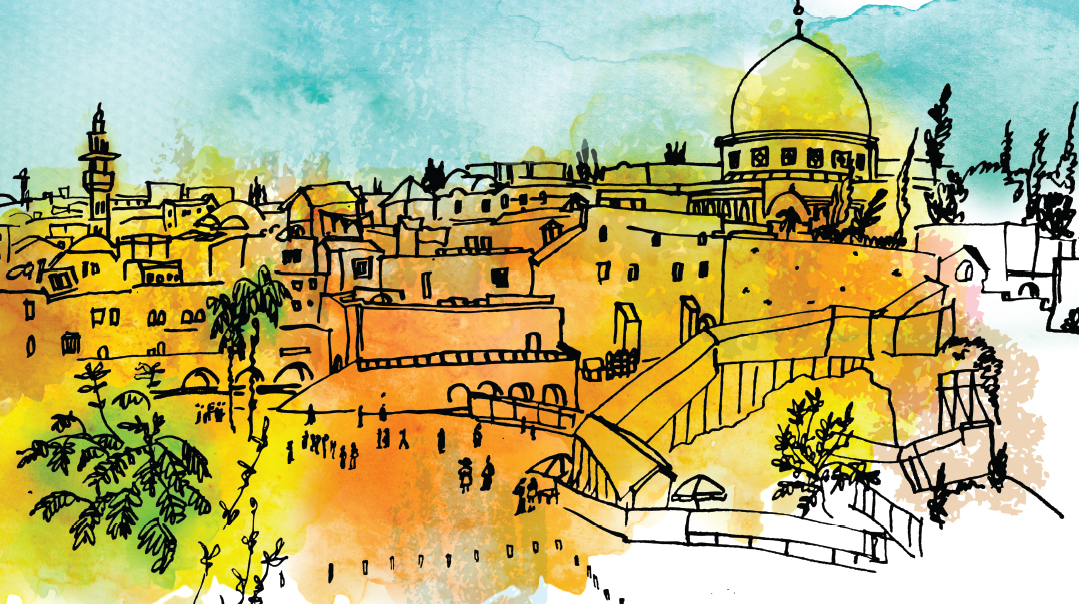

Just as she thought: The pinks have faded over decades of touch and wear and drippy droplets of rain slipping through spaces between sechach. Last year, she’d retouched the golden-yellow tones of the sunrays over the mural of Jerusalem. This year she starts with the pastel-toned houses, dream homes, all arched doorways and domed roofs.

Her paintbrush flicks deftly over her handiwork.

The boys will be home tomorrow.

She steps back, eyeing the mural critically. Light slants through the roof and scatters sunshine unevenly across her paintwork. She reaches for the brush again.

The twins are coming. Finally.

About time, she thinks to herself, as she dabs yellow ochre onto the ends of sun-drenched palm fronds. Six months, nearly. She still can’t believe she let her little boys leave home for so long.

Sol can laugh all he likes at the way she marked off days on the calendar, week after week, until the red-letter date is circled over and over, but it’s her motherly right.

The succah has to be all ready, she decides. She’ll do it herself, decorate it just as they’ve always done. The mural across the length of one wall makes the job easier.

Sol brought down the box of old pictures already. A few photographs she’d taken years ago, enlarged on canvas by the studio she’s worked at for the past two decades. Another painting, some paper chains the boys brought home from school in another lifetime.

She digs further. The pictures, they must be here somewhere.

Of course, they’re the very last things she pulls out. Two drawings, as close to identical as the twins themselves. She’d drawn them, one for David, one for Aaron, when they were five or six.

A lifelike portrait of Mickey Mouse shaking lulav and esrog beams up at her from each page. She remembers how excited they had been at her artwork, how the two of them had sat for the better part of an hour painstakingly shading in the black-and-white drawing, so intent on making the pictures “match” that the process took double as long.

They belong right in the middle of the wall opposite her painting, between the two windows.

When Honey is done, she closes the succah door securely behind her. Everything is just as it always was. Everything is perfect. Now the boys can arrive.

If not for the identical face-splitting smiles and cinnamon freckles, Honey might not have recognized her boys. She stares.

They did not go to Israel with those bar-mitzvah-boy hats. Surely not.

Aaron hurries over and David embraces Sol, who is muttering something in her ear that she can’t quite process.

“Mom!”

There are hugs and exclamations and, “Hang onto that luggage, boys,” from Sol, who sounds bemused.

She hangs back. “You look... different,” she stutters, looking from one to the other.

The twins exchange a look.

“It’s our yeshivah, Mom, all the guys dress like this.” David tries for an airy tone. Aaron tips his hat back jauntily, clearly trying to mask the discomfort. She blinks hard.

His hair—

“You’ve cut your hair so short,” she says, like that even matters when her sons have just walked off a plane looking like full-fledged rabbis, strings sticking out and all. “Didn’t you like your curls how they were?”

Aaron looks almost guilty as he rams his hat straight again. “Easier with the kippah and hat this way, sorry, Mom.”

She sniffs. “Oh, it’s your choice how you look, I guess.” It’s ungracious, but at least she isn’t picking a fight before they’ve even gotten home.

Sol changes the subject inelegantly. “Come, let’s get your things out to the car.”

“So, are you up to eating out with us tonight? Or you just want to sleep?” Honey tries to catch their eyes in the rearview mirror. With their hats on laps, the twins sitting squeezed between duffel bags in the backseat of their old family car, things feel familiar again.

“Uh, where were you thinking of eating?”

She has never heard either of her sons stutter. “What?”

“Like, which restaurant?”

She frowns. “SuperGrill, The Deli, wherever. Somewhere nearby. You know, the regular.”

The look passes between them again. It’s starting to irk her.

“Mom,” they start together, and both grind to a halt.

“You can,” David mutters.

“Gee, thanks, bro.” Aaron leans forward and raises his voice. “Mom, it’s like this. We’re — we don’t wanna eat at those places anymore… they don’t have the best hashgachah. Unless you want to drive further, like into the neighborhood near shul…”

She is struggling to choose between anger and martyrdom.

“I don’t think we have the time for that, Aaron. I guess if you can’t do the grill place or whatever, we’ll stay home.”

“We’re tired anyway. It’s okay.”

“Need to get some sleep, yeah,” David adds. “Maybe we’ll make some sandwiches or something.”

“Oh, I don’t know what we have in the house. I really thought we’d eat out. I didn’t realize all the rules had changed.”

“We can pick up bagels from the bakery on our way home,” Sol interjects mildly. She glares at him. When did she turn so nasty? She should’ve been the one offering bagels. Her stomach twists.

The twins look relieved. “Thanks, Dad, yeah, that would be great.”

She leaves them eating their bagels at the kitchen table, which is suddenly cramped again. They are regaling Sol with yeshivah life experiences, and although she waited half a year to hear this, it’s lost the glamour now.

“Going to check on the succah,” she mumbles. Sol nods, distracted. He doesn’t notice that her own bagel is still untouched.

She unbolts the back door, looks around. It’s as perfect as she left it. The paint has dried overnight, and in the dusk, the mural glows with day’s last light.

She stares at the brightly decorated walls, the posters. Yesterday it seemed happy and colorful, today she feels like the world has moved on and she’s the only one in a time warp. The succah is childish, all finger paints and Magic Markers.

Everything is just as it always was. But nothing is the same.

The Mickey Mouse portraits are smiling too widely. Their eyes, huge and sparkling, hold the memories of simpler times. Her heart aches.

Honey reaches up and pulls them off the wall. Then she buries them in the deepest part of the box and shoves it into a corner.

Everyone at shul has noticed that the boys are back. The black Borsalinos, standing out in stark contrast to the array of knitted kippahs and the occasional straw hat, draw all the attention.

“Are those your twins?” Mrs. Fogel asks in a stage whisper, when the rabbi stands for his speech. Honey nods stiffly.

“Unbelievable. Imagine your boys flipping out!”

For the first time in years, she leaves shul before the kiddush. She tells Sol she needs more time to prepare the meal. It’s true, sort of. In honor of the twins’ arrival, she’s prepared brisket in wine sauce, hot chocolate cake, and an extra salad. She and Sol don’t go for too much food on Shabbos morning, but the boys will like it. They’ve invited guests too, the Kellers from down the block, old family friends. The twins will enjoy it.

Honey arranges the foil pans to warm up, and heads upstairs to put her hat away. When she comes back down, the boys are back, conferring in the kitchen. The Kellers are comfortable on the sofa, and Sol is sitting at the table with the newspaper, placid as ever. Did he get comments about the change in the twins? She can’t tell.

“Lunch?” she asks brightly. Today, she decides, she’s going to avoid any awkwardness.

The boys look uncomfortable when they come to sit down, but Honey decides not to notice. She asks them how shul was and David says, “Fine.” Then Sol starts Kiddush, and the conversation is over.

“Delicious challah,” Lisa Keller says. She passes another piece to her husband, who gives a grunt of thanks.

“Yeah, great challah, Mom,” one of the twins echoes. Somehow, coming from him, it annoys her.

“So, boys, you’re back?” Mr. Keller booms. “How’s it been? The rabbis convinced you to stay another year?”

Honey flinches. The boys shrug.

“No one did any convincing, we love it there,” David says.

“That’s what they all say,” Mr. Keller shrugs, jovial. “As long as the kids are happy, eh, Sol?”

Honey narrows her eyes. Sol gives a half shrug. “More challah, anyone?”

She serves the salmon in a thickening silence. Sol repeats what the rabbi said in his Friday morning shiur. The boys nod along, but Honey wonders if they’re even listening.

“What’s going on?” she finally asks, looking from David to Aaron and back. “Why are you so quiet?”

“We are?” Aaron asks, but he is clearly uncomfortable.

David coughs. “Sorry.”

The Kellers shift uncomfortably, but she is too irritated to stop there. “Why sorry? You’re not doing anything wrong. I just asked why you’re being so quiet.”

The awkwardness is back. She’s ruined it now.

“Forget it, I’ll go get the next course.”

David jumps up. “Wait, Mom, I’m— we—”

“We’ll come and help you.” Aaron says, smoothly.

The boys bring in the cholent and she unwraps the foil, laying out the brisket on a platter and spooning the wine sauce on top. It’s been ages since she’s used these serving dishes.

“Everything looks fantastic,” Lisa says.

“Tastes fantastic, too!” her husband adds. He has a heaping portion of cholent on his plate, but he hasn’t sampled anything else. Honey tries to smile.

“I’m just going to have a little taste of everything, if that’s okay, I don’t like to eat too much at lunch.” Lisa leans over, takes a thin slice of brisket.

The boys compliment her cholent, and she offers them the other dishes. Everything’s getting cold, they should eat already. David looks at Aaron. Aaron looks back and shrugs.

“We’re not so hungry, Mom. The cholent is great though.”

Her mouth drops open. “Not so hungry? At least try the brisket.”

Sol puts down his spoon. “Your mother cooked the brisket in wine sauce especially for you,” he says mildly. “Us old folks don’t eat much after cholent, but surely two yeshivah boys like you don’t fill up that easily?”

The twins exchange an agonized glance.

“Mom, it’s… we feel really bad about this,” Aaron stammers. “We — we can’t eat the brisket. It’s… it’s nothing personal.”

There is hot, thick anger in her throat, mingling with the taste of a slightly overcooked cholent. “What do you mean by that?”

David looks away from her when he answers. “It’s the hot plate… We learned that you can’t put anything on it on Shabbos… for sure not liquids. I — we just can’t eat the food that was warmed up today, Mom.”

The Kellers are staring at their plates like the wisdom of the world is concealed beneath the cholent beans. Honey feels hot lava explode from under her chest. Mortified. The words boil and bubble inside her, but she can’t open her mouth, she’s too afraid of what might come out.

“We’re really, really sorry,” Aaron says hurriedly.

“We’re sure it’s all really good,” David adds.

The words are a volcanic eruption, no — a tidal wave. Honey clenches her lips. She is not going to speak. She is not going to scream. She is definitely not going to burst into tears.

She clears the cholent and the brisket in silence. The Kellers compliment the food too loudly and then hurriedly leave — they have somewhere they need to be, apparently. She stuffs the rejected love-offerings in the back of the fridge, and after a moment’s thought, removes the hot chocolate cake from the hot plate as well. The twins won’t be eating it, Sol should be watching his sugar intake, and as for herself — nothing is going to taste sweet today.

The cat is scrawny, long-legged and one-eyed. Her hand flies to her mouth.

“Oh my, poor little thing!”

Her exclamation is loud enough to draw the twins’ attention from inside the succah. It’s the end of the second day of Succos, long enough after the Shabbos disaster for her to thaw, but not to forget it. The boys haven’t forgotten either; they are overcompensating by complimenting everything too loudly.

“What’s that, Mom?” David pokes a head out of the doorway. His velvet kippah slides to one side, and for a moment she stares at the uncovered patch where the curls used to be. Then she turns back to the woebegone creature, and crouches to the ground.

“Poor kitty! Look at her. Dave, go get a dish and some milk. She looks like she’s starved.” Honey reaches out a hand. “Here, kitty, kitty, come.”

“Uh, Mom, animals are muktzeh.”

She looks up in annoyance. “I’m not touching a stray, okay? Not until I’ve fed it, anyhow.”

David shrugs and strolls inside.

“What a beauty you must be, under all the mud,” she murmurs. “All striped and ginger. I wish I could clean you off, but David says I mustn’t touch you today.” She can’t help her voice turn sour at the last part. She’s never heard of any problem touching animals, anyway. Wouldn’t Rabbi Joseph say it was fine?

David comes out with milk in a bowl, and she sets it down, close as she dares to the cat. “Here you go, darling.”

The succah door slams shut and she hears the twins’ voices, pitched too low for her to make out the words. Since Shabbos ended, they’ve come to an uneasy truce of sorts, but something inside her was lost with the discarded brisket. Things will never go back to how they were.

She turns her mind away and focuses on the tiny pink tongue, lapping desperately at the creamy liquid. The milk speedily disappears. Honey waits until the cat licks a paw, regards her out of its one bright eye, and finally wanders back into the bushes. Then she picks up the bowl and goes inside, to the kitchen, of course. The succah door is firmly closed.

Kitty returns late that evening when sun dips to the earth and magical hues color the horizon. This time, she is waiting.

They stare at each other, Honey’s small brown eyes gazing into the one unblinking amber light.

Then the cat takes a single step forward.

She has prepared milk already. Dropping to the grass, she inches closer. The cat laps on, undisturbed by her presence. Conquered.

Sol raps on the window and Kitty’s tail flies into the air as she arches her back. Honey twists around and gestures frantically. He recedes from sight, shrugging.

“Come Kitty-coo, come. It’s okay. That was just—”

The cat regards her with suspicion for one moment. Then she ducks her head, takes one last sip at the milk, and darts off. Honey watches it go.

From the corner of her eye, she sees David and Aaron, lugging their inflatable mattresses back out through the garden. This sleeping in the succah business again. She frowns. It’s cold, and is it even safe to do this? A shame their rabbis never consulted her about the idea before firmly planting it in her sons’ heads; her answer would have been a resounding no. But they had stated their case so nonchalantly, so assuredly — “Mom, we’d like to sleep in the succah this year, it’s a real mitzvah for boys and men who can do it” — and since when has she ever been able to say no to her boys?

Still, she thinks, as they wave cheerfully and yell “Hi Mom, gut Yom Tov, good night!” loud enough for the Kellers down the road to hear, Sol never slept in the succah. It can’t be that important, surely.

She starts to get up. She wants to follow them into the little wooden hut that they’ve claimed as their own territory, and ask them why. Why it matters, and what difference it makes, and if things can be the same if everything has changed.

Then the door closes firmly behind them, twin banter is swallowed inside, and she is left alone with a nearly empty milk bowl and the wind.

The Havdalah set has been cleared away and Honey is balancing a tray of too many things as she makes her unsteady way across the garden, back inside. Just her luck — Mrs. Stone is outside, puttering near the low garden fence too casually. That woman doesn’t seem to have anything better to do with her time than spy on Honey’s family. Succos must be her favorite time of year.

“Bit noisy for the evening, aren’t you,” she calls to Honey.

She stops short and the glasses on the tray slide a little. “I’m sorry if we’ve disturbed you.”

Mrs. Stone cackles from deep in her throat. “Disturbed me? Oh, dear me, not at all, what am I doing that’s so important, anyway?”

Honey gives a wide, fake smile.

“But your old neighbor’s done her good deed for the day, oh yes she has.”

The tray is heavy and her legs ache. She edges toward the house. Mrs. Stone walks along the fence, unwilling to end the conversation.

“Don’t you want to hear about my good deed, Honey?”

She sighs, balancing the tray against the porch railings. “Sure, tell me, Mrs. Stone.” This had better not take too long.

The elderly woman permits herself a smile of triumph. “It’s simple. This afternoon, I spotted a poor little injured cat wandering around our gardens.” She sniffed. “It walked through mine, if you please! So I called them, killed two birds with one stone, as they say: It doesn’t bother us, and it’s given real care. Wouldn’t want a dead animal in someone’s garden on the morning. That cat looked like it was on its ninth life alright.”

Honey’s mouth falls open. “You called who?”

“The ASPCA, of course. A creature like that? Someone has to take care of it, you know. And no one in our cul-de-sac’s doing that, I tell you.”

Someone was doing it, Honey thinks, but her mind is still groping for a way out. “But a stray cat? Do they really come out for stray animals?”

“Of course, if it’s in trouble of some kind. And this thing certainly looked like it was.”

She can’t breathe. “What — what will they do?”

Mrs. Stone chuckles again. To Honey the cackle suddenly sounds remarkably like the Wicked Witch of the West. “What did they do already, do you mean? They came for it — oh, about an hour ago.”

“And did they…” She lets her voice trail off. Surely, surely Kitty wouldn’t have allowed herself to be caught like that. Cats were quick. Cats were suspicious and alert and they were master escapists. Surely Kitty got away?

“Caught it quick as a lick.” Mrs. Stone beams with satisfaction, as if it had been her skills alone that led to the cat’s abduction. “Showed it to me to make sure it was the right one. One eye and all. I told them it certainly didn’t belong to anyone, and it’s a poor starving mite and needs a home.”

“Where did they take it?”

Mrs. Stone frowns. “Well now, I can’t say I know. They did say that it’s not so easy to find a home for an animal like that… that it would have to be taken to an animal shelter for a while. Wait and see if someone comes to claim it.”

She has heard all she needs to hear. Honey wheels around, barely tossing a goodbye over her shoulder. She leaves the tray smack in the center of the kitchen table and heads for Sol’s study.

She types “Animal shelters in my neighborhood” and a hundred results instantly appear on the screen. She tears off a piece of notepaper and starts writing.

“What were you planning to do today?”

She looks up, closes the notepad guiltily. Sol is standing over her, a mug of tea in his hand, bemused.

“Who — me? I didn’t have plans.”

Or maybe I do. There’s a shelter nearby… surely that’s the one Kitty was taken to? Or maybe it’s the one that’s a little further away, that specializes in caring for injured animals.

“But — first day of Chol Hamoed? Let’s take the boys out somewhere, maybe that waterfall-trail mini-hike, we haven’t been there in ages.”

She makes a face. “I doubt they’ll want to go. They’re busy out there.”

Sol rocks back on his heels. “Busy?”

She pictures them coming home from shul, those large-size Gemaras under their arms. “Hi, Mom, thanks for breakfast. Can we eat in the succah?”

She shrugs. “With their Gemaras.” A little bitterness seeps into her tone. They live in a different world now, her twins.

“They’re not doing Gemara all day, they’re on vacation.” Sol says firmly. “I’m going out to them.”

Honey makes an elaborate show of looking back at her notes, but she doesn’t read a thing.

“Mom, hey.” Sol is back, the twins following behind.

“Mom, what’s up?”

They’re making an effort, apparently.

“Nothing much. What are you boys doing today?”

Aaron and David look at each other and back at her.

“Aren’t we going out somewhere?”

She darts a glance at Sol. He must’ve put them up to this. But he gives her a guileless look and spreads his palms slightly as if to say, see, Honey?

Her heart twists in so many directions. Yearning. Rebellious. Jealous.

“I thought you were busy learning.” She keeps her tone carefully neutral.

“We’re finished.”

“Just a little, Mom.”

They look at her expectantly. So they’re done, are they, finished with their huge, gold-embossed books and now they can give their old mother some time?

The rebel wins out. “But now I’m busy. I’m… I have something I need to take care of today.”

The twins stare. Sol clears his throat.

“But Honey…”

She shoots him a glare. Don’t contradict me in front of the kids.

David and Aaron glance at each other, and then David speaks for both of them. “But Mom, it’s Chol Hamoed. It’s the best time to go out together… and we’re back in Israel soon.”

She slams the notebook shut; the pages flutter in protest. “Oh, really? So then why weren’t you two around to eat breakfast with your parents? To make plans earlier in the morning? Don’t we always go out together on Chol Hamoed?” she finishes with a cruel mimic. Let them flinch, let them see how it feels when the rules of the game change in your face. Don’t talk to me about how things have always been.

“Honey,” Sol says in a patronizingly calm voice. “Come on. The boys just wanted to learn a little. It doesn’t mean we’re not spending the day together.”

She breathes deeply. “Everything is not the same, Sol. Everything has changed, so why are we pretending it’s the same as always?”

The twins find their tongues again. “Mom, we still want to go out. Nothing to do with the learning or anything else. We want to spend time with you.”

She’s waited a whole week to hear that, but she’s too far gone to back down now. “I’m busy today,” she repeats, wooden. “Maybe tomorrow. Today I’ve got other things to do.”

The twins are back in the succah, closeted between the mural and the over-cheery wall decoration. She goes back to her shelter-hunt, trying to feel victorious. She’s given them the message now, parents aren’t just a take-it-or-leave-it, you don’t waltz home and turn the world upside down to suit you and then innocently ask why things have changed.

But the reasoning doesn’t do anything for the ugly pit in her chest.

The map on her phone screen blurs before her eyes. Seriously, Honey? You’re choosing a cat over your boys?

They’re not mine anymore, she thinks, fiercely.

Yes, they are. They want to keep something the same, despite it all. And they came home, Honey, they came. They’re holding on too, somehow, even as their life takes them on a journey they never imagined till now.

She thinks of the shelter, of a one-eyed kitten without a home. As if that will make it all better. There is an ache in her heart, before it was bitterness and resentment and guilt, but now she wonders if it is really love, disguised. It’s too big, too full, too overflowing. A cat won’t make things better.

Sol’s tried his best to reconcile everyone, Sol always does. Dependable, ever-steady Sol. But it’s not him she needs, it’s not even the boys.

It’s her.

Honey stands. Her feet are a little unsteady for a moment. She spots Sol in the living room, studying the newspaper with his feet propped up on a footstool.

“Let’s go on that hike,” she says.

Sol looks up, scrutinizes her, then slowly nods. “Sure.”

She heads to the stairs for her sneakers. “But you go tell the boys.”

The song seeps through the crack under the succah door and floats in through her open kitchen window. The twins are singing again.

Honey turns up the faucet. Soap suds burst under the onslaught. All these Hebrew songs, all these tunes she’s never heard before. Where do her boys come from? They were always hers, hers and Sol’s.

She picks up a plate, wipes, sets it down on a towel to dry. The song changes, something vaguely familiar. Maybe one of the neighbors sings it?

Her heart aches. The twins, her little boys, they have grown up. There are so many parts of them that she doesn’t know anymore.

The water is running over her wrists, but Honey is staring out the window. Where is the faucet to her heart? She’s lost something, she’s lost the childhood, the sense of belonging, that she is her sons’ and they are hers, only hers.

The hike was… nice. Nice, but full of those awkward silences where the twins stopped and started and looked at Sol for support. She’d kept quiet, mostly. No sense in starting another fight.

Sol is behind her. She can hear his lumbering footsteps. In a moment he’ll be at the fridge, rummaging for an apple.

He takes a bite and she half-smiles. Good old dependable Sol.

“I don’t like change,” she tells him, apropos of nothing.

“That hasn’t changed in the last thirty years,” he quips. She laughs aloud.

“But that’s all it is, right? It’s just change.” She sighs.

Sol is not given to pondering, but he stops at the door, on his way to the recliner. “Honey, give it time, it’s a big change. The boys are growing up.”

When she turns back to the window, the song has changed. This time, it’s so familiar that the tears finally come, wavering in the corners of her eyes. It’s their song, the one they sing each Succos, Sol and her boys. If only everything else were the same, too…

Really?

The ghost of a one-eyed cat flits through her consciousness. She had to admit that Mrs. Stone was right; Kitty needed real care. Sometimes, change is good. Maybe she should have done it herself, maybe she would have, if not for all this. If not for Kitty having been the first thing all week to really need her.

It’s all so confusing, Honey wants to block it all out, but the thoughts crowd in. She gives up on the dishes, sits down by the kitchen table. Stands up again, opens the back door, and takes a step toward the songs.

One step. I want my sons to grow up.

Two. I want things to stay the same.

Three. Growing up involves… changes.

She stands stock still. Of course growing up means changing. That’s not the sort of change she dreaded; not the transition of schoolboy to college student to family man. That’s predictable change. That’s what she’s always wished for her boys.

It’s this insidious sort of change, eating away at their relationship from the inside, destroying not just the future, but also everything that has ever been, that she fears.

It’s like their childhood, everything she and Sol tried to give them, is worthless, discarded.

She feels better and worse for thinking it through. Maybe Sol had been right, and she should’ve just given it time. Let things be.

She’s halfway down the garden, though. It’s too late to let things be. She walks into the succah before it’s a conscious decision.

“Mom!”

Two laughing voices, two tousled heads, wisps of beards.

“Welcome to our bedroom!”

The succah is a mess; the boys have moved the table and stacked chairs precariously to fit in their mattresses. She leans against the stack of chairs, gingerly.

“You heard the singing, Mom?”

She nods and shivers. It’s cold in here. There’s a sweater of hers draped over the chairs, and she slips it on. “Of course I could hear you.”

“Remember how we used to have singing competitions in the succah, so that the cousins should hear us on the next block? They never did,” David remembers.

Despite herself, despite everything, she smiles.

“You boys have long memories.”

David shrugs. “It’s not that long ago, Mom.”

Aaron grabs his twin by the shoulder, starts bellowing into a fake microphone. “Am Yisrael Chai, Am Yisrael chai…”

She says the words before she can think them through: “I taught you that song.”

Aaron stops for a fraction of a second, and David says, “I remember that.”

Maybe they’re more hers than she’d thought.

She sits back, lets the song flow, forgets the dishes in the sink, and time stands still for one delicious moment. Then the notes die on the night breeze, her sons are looking at her expectantly, and she realizes they aren’t sure what to say. Her sons, with their close-cropped hair and velvet kippahs.

“You did fun stuff with us, Mom,” Aaron says, finally. “I remember when Dad built the succah every year, and when you painted the mural. I wanted to do some and you wouldn’t let, but then when you went inside for a minute, I sneaked in and added a tree in the corner, here.” He grins. “Did you ever realize?”

“What?” she looks closer. “My, you’re artistic. I never even knew. You should’ve taken art classes.”

Aaron shrugs. “Wasn’t really that interested. I just wanted to be a part of this crazy painting. I’d never seen anything so big before.”

They laugh. The silence that falls now is warmer.

“Don’t we all want to be part of something bigger,” she muses. She expects them to nod blankly, but David looks serious and Aaron opens his mouth to speak, then closes it again.

And she understands.

They are part of something bigger, something greater, but they are still hers. She created the shelter that held them for long enough that they aren’t afraid to experiment, to grow.

“We get that from you, Mom,” David says. “You always think big. Like that mural.”

She gives a lopsided smile. “I never thought of it that way.”

“And speaking of my artistic talents, Mom…” Aaron holds up a picture, the old painting she’d stuffed into the corner. How did he find it? “Why isn’t this up on the wall? We always put it there.”

“I — I don’t know, they’re so old.” She tries a little laugh. “I thought we’d moved past Mickey Mouse, you know?”

“But Mom, they belong up here.” Aaron points to a spot halfway up one whitewashed wall. A pin-prick, souvenir of an old nail, lies just above his pinkie.

“They’re the most important part of the succah, aren’t they?” David adds, half-joking, half-nostalgic.

They’re already hunting down the hammer and nails but her mind is turning over the last few words.

Honey picks up one Mickey Mouse-lulav-esrog drawing, awash in watercolor paints and glowing faintly still with enthusiasm.

No matter that that youthful happiness is now clothed in black and white, and adopting customs she may never understand. No matter that her dreams have grown wings and their journey has taken them far, farther than she could ever have imagined. Because as long as that joy lives on in their eyes, she is a part of them.

She always has been.

Aaron tugs the paper from between her fingers. “Here, Mom, let me hang this up.”

David passes him the hammer, all seriousness.

“Hey, that one’s mine. I’m putting it up.”

“No way, Jose. You painted out of the lines, remember? This one’s mine.”

“I’m older, I choose.”

There is a friendly tug-of-war over the hammer and familiarity draws tears into her eyes. Honey blinks. Inside the house, the downstairs lights flicker off, one by one. The grandfather clock in the hall strikes eleven-thirty, a single chime. Sol will be on his way up the stairs now.

Some things never change. It feels good. But some things… some things are supposed to change. And the only time warp exists in her heart, when it’s fixed in the past instead of embracing the journey to the future.

She lingers a moment before leaving, watching these little boys she knows so well, little boys who live on inside the men they have become.

“The lights will be out soon in here,” she warns. “We’re still on a timer.”

David gives another pound to the nail. The sound of cracking wood fills the air. She sucks in a breath.

“Don’t worry, Mom, we can hang pictures in the dark,” Aaron grins. “Worse conditions than this in the dirah.”

“I shudder to think of it.”

The boys laugh, and she lets a soft chuckle escape, too.

With a faint click, the electric lights go out. The succah is blanketed in darkness. Honey feels the walls close in, embracing her and her sons. The mural and the Mickey Mouse drawings and the tzitzis and brand-new negel vasser cups and her artsy Venetian-glass candlesticks. All of it together.

Her arms drop to her sides. Long threads of fur cling to her sweater and she dusts them to the earthy ground below. Her heart is too full to be weighed down now.

She steps out into the silver-studded darkness. The rhinestones on her sandals glow in the moonlight. Honey breathes, exhaling lonely, inhaling harmony.

Her hand is on the doorknob when she hears a rustling sound in the rhododendron bushes. She looks back, the bushes draped in shadow, her family’s shelter outlined in moonlight. For a moment, she thinks she can see the flash of a ginger-striped tail, but then she blinks, and it is gone.

(Originally featured in Calligraphy, Issue 781)

Oops! We could not locate your form.