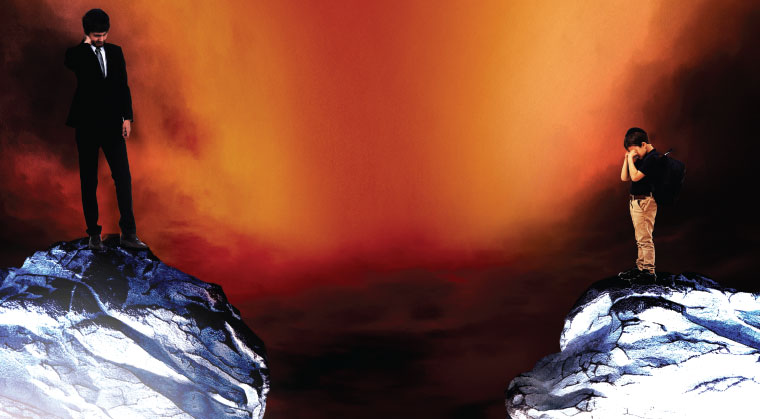

Rejected by My Children

Is there a way to bridge the abyss when your ex turns the kids against you?

It was a perfect picture, the kind you’d stick in a family photo album: three smiling girls in matching outfits on a sunny afternoon, embracing their Tatty as they revel in his attention while licking triple-scoop ice cream cones. But what started out as a Sunday dream morphed into a family nightmare — it was the last time Baruch saw his daughters in four years.

Baruch and his first wife divorced close to a decade ago after a marriage that was stormy from the outset, and their three little girls were put into joint custody — Baruch had them every other week from Thursday to Monday morning, and one overnight in between. Less than a year later, Baruch remarried and his new wife, Liba, joined in the custody of the girls (“they were really just babies at the time,” she says) and raised them together with her own four children. For three years this new blended family found its rhythm, weathering some precarious custody battles in the interim — like the time Baruch’s ex filed an emergency petition in court claiming that he was a drug addict who regularly beat the girls and locked them in the bathroom. For two months, while she railed against him to the children, he wasn’t allowed to see his daughters; he was finally cleared after a series of drug evaluation exams came out clean, and after a court-appointed therapist determined that not only was Baruch not a danger to his kids, but that he was a devoted and stable father and there was no reason he shouldn’t be allowed to see his children.

According to Baruch, an active member of an Orthodox community on the East Coast, that was just the beginning of a painful and tragic ongoing scenario known among therapists and clinicians as “parental alienation,” a conflicted family dynamic in which one parent (the alienator) employs a set of strategies to try to create a child’s rejection of the other parent (the target). The alienating parent accomplishes this estrangement by creating extreme negativity toward the targeted parent by sharing deprecating comments, all-encompassing blame, and false accusations with the children against the targeted parent. The alienating parent usually hoards the kids as well, doing all he/she can to thwart the other parent’s time with them and creating a strong (and generally unfounded) sense that it’s dangerous/unhealthy/scary/awful to be with that parent.

Stay Away from Us

The children eventually came back to Baruch and Liba for their regular visitations, but the anxiety was palpable — seeds of fear and distrust had already been planted because of the protracted separation, exacerbated when the girls’ mother bought them each a cell phone for the visitations and told them, “If you ever don’t feel safe with Tatty, just call me and I’ll pick you up.”

In fact, that cell phone was used by the seven-year-old — a sensitive yet difficult child who was traumatized by the divorce and the subsequent remarriage of both her parents — to call the police one Erev Shabbos when she got upset that her father told her to hurry and take a shower. An hour before Shabbos, the police showed up at their house, took in the situation, and before giving the all-clear, calmly explained to the little girl that she can’t call the police just because her dad told her to do something she didn’t want to do.

But what does it do to a father-child relationship when the child wields so much age-inappropriate power and has such a distorted view of how to use it that she could send her own father to jail? Baruch and Liba would find out soon enough. Another incident involving the fallout of a tantrum became the catalyst for the final separation: Baruch and Liba were on the way to a family celebration and would be picking up the girls, when the texts started coming in: “We don’t want to come.” “You’re so mean to us.” “We’re never coming back.” “Stay away, we don’t want you anymore.” And then from their mother: “Don’t try to pick them up, they never want to see you again.” “If you come near here, we’re calling the police.”

After that, Baruch filed a motion in court, which resulted in the court ordering all the parties to go to family therapy in order to put the relationship back in order. The court also declared that the girls can continue regular visitations if they want to. But the court had no intention of forcing everyone into therapy, and so in the last four years, Baruch and Liba saw the girls just once, for an hour in a restaurant, when a relative from Florida was in town.

The sad irony of this scenario is that there is in fact no legal impediment to the visitation, and Baruch continues to pay child support and half of their tuition every month. But what to do if the children are manipulated in a way that they have no way to navigate emotionally, if wanting to rejoin the family would create so much tension and fear that it just becomes easier for them to reject it?

The way Liba reads it, “They aren’t at the age where they’re equipped to deal with that level of trauma. They can’t defy their mother because they can’t risk losing her love, so they have no choice but to completely cut off from Baruch in order to keep themselves emotionally safe. I can’t really blame them. They’re just kids — they don’t have the tools to deal with that level of pain and confusion.”

Betrayed

Therapists knowledgeable about parental alienation — when one parent manipulates a child to reject the other parent for no good reason (not when the rejected parent is abusive or otherwise a danger to the child) — would say these children are suffering from something called Parental Alienation Syndrome (PAS), which is the resulting behavior of the child who comes to believe, unjustifiably, that the targeted parent is evil and unworthy of having a relationship with. The term was coined in the 1980s by child psychiatrist Dr. Richard A. Gardner, who, drawing on his clinical experience, believed it to be a specific psychiatric syndrome, defining it as “a disorder that arises primarily in the context of child-custody disputes. Its primary manifestation is the child’s campaign of denigration against the parent, a campaign that has no justification. The disorder results from the combination of indoctrinations by the alienating parent and the child’s own contributions to the vilification of the alienated parent.”

While PAS has not officially been acknowledged as a pathological syndrome by the American Psychiatric Association (when it was first proposed, some women’s groups dismissed the syndrome as something concocted by lawyers for abusive fathers trying to improve their custody chances), parental alienation is in fact a very tragic and real phenomenon. According to Dr. Amy Baker, director of research at New York City’s Center for Child Protection and a nationally recognized expert on parental alienation, children who reject one parent in order to please the other will manifest their conflict as a campaign of denigration of the targeted parent using weak or absurd reasons for the rejection, will show lack of remorse for the poor treatment of the targeted parent, and will show animosity to friends and family of the targeted parent as well. They reject the targeted parent without justification, as their feeling toward the targeted parent is based on the emotional manipulation of the alienator, rather than actual experiences with the targeted parent. And of course, PAS is only considered when the child is being manipulated by one parent to reject the other parent for no solid reason — and not if a parent is actually abusive or dangerous.

Alienation strategies include poisonous messages to the child about the targeted parent in which he or she is portrayed as unloving, unsafe, and unavailable; limiting contact and communication between the child and the targeted parent; erasing and replacing the targeted parent in the heart and mind of the child by a continued litany of negative remarks; encouraging the child to betray the targeted parent’s trust; undermining the authority of the targeted parent, and forcing the child to choose (“If you pursue a relationship with him, it will jeopardize your relationship with me”). Short of the death of a child, says Dr. Baker, alienation is one of the most tragic and painful things a parent can go through.

Baruch would concur. At some point, he says, he realized that his relationship with his girls — for the time being, at least — was lost. The girls had cut him out of their lives. The pain, he says, has been excruciating.

“When children are alienated from a parent, the parent’s very identity begins to erode,” he confesses. “Many alienated parents struggle with their Yiddishkeit, as we question how Hashem can let this happen to us and to our children. We struggle with davening, praying daily to have the relationship with our children back, and yet our tefillos seem to go unanswered.”

Missing life-cycle events, says Baruch, is devastating. He’s already missed two daughters’ bas mitzvah celebrations. “I wonder if I’ll even be invited to my own daughters’ weddings,” he says.

Baruch channeled his pain and despair into forming a support group for frum men who find themselves targets in the alienation dynamic. Today Baruch has 16 fathers in his group, all of whom claim they’ve been the targets of alienation and most of whom haven’t seen their children in months or years. They call each other for support when the pain becomes overwhelming — it’s somehow easier when it’s shared. They’ve also recently launched a website called “Jews for Equal Shared Parenting.”

“Some people still have this idea that ‘by us, these things don’t happen,’ but I’m in touch with too many devastated families in our wider community to know that alienation doesn’t discriminate,” Baruch says.

“We believe that the most effective way to reverse the trend of alienation is by changing how the secular courts look at co-parenting after divorce,” he explains. “The way the system is currently designed, it’s easy for children to be used as pawns for leverage in a settlement, and where either parent can force the other to prove his or her worthiness in continuing to have an active role in their child’s life. We want to see a system that will ensure the rights of the children to have equal access to both parents from the very moment that the parents agree to separate, which will eliminate future exploitation of children as leverage for negotiations and would also eliminate many of the degrading tactics such as the unrestrained, wanton use of psych evaluations, restraining orders, and other abusive tactics alienating ex-spouses use to drive a wedge between parents and their children.”

Shimmy can testify to that. He’s fortunate that he doesn’t have supervised visitation, but he’s fighting to maintain that following claims of abuse by his ex — which he says is the classic first-line tactic used by an alienating parent. “If my lawyer didn’t smell the truth and dedicate himself to this, and friends didn’t step in to pay the many legal bills, I’d have extremely limited access to my kids. One of the terrible things about alienation is that a child is left with no choice but to believe that the alienated parent doesn’t care about them to spend more time with them. My son recently asked if he could spend more time with me, and when I said ‘unfortunately no,’ without putting the blame on his mother for limiting access, he said ‘Oh, because Mommy said it’s up to you.’ So now he thinks I’ve rejected him.

“People don’t realize that not all mothers who are getting divorced are leaving men who don’t want to be awesome fathers,” Shimmy says. “Baruch Hashem our community has found the heart to care for divorced mothers. But unfortunately, due to that, some women get well-meaning people to support their lies. From lies about child support, to lies about my willingness to spend time with my boys, my ex does what it takes for her to come out on top, even at the expense of our young sons.”

Does that mean that kindhearted, community-conscious activists and askanim actually enable alienation at some level by embracing the alienator?

“It’s a real tragedy, but I don’t think it’s fair to say the community is looking away,” says Rabbi Yosef Viener, popular Torah lecturer and author of Contemporary Questions in Halachah and Hashkafah, who is mara d’asra of Kehillas Sha’ar Hashomayim in Monsey and former rav of Agudath Israel of Flatbush. Due to his wide breadth of exposure with a plethora of on-line shiurim, seforim, and speaking engagements around the country, Rabbi Viener has been called and consulted by people from different sectors throughout the Jewish world and has found himself navigating many messy family breakups.

“There are a lot of good people within our kehillos who are trying to set these situations right,” Rabbi Viener says, “but sometimes their involvement only gets them in trouble and they suffer because they try to help. We live in a democracy with a police force and a court, so it’s not simple to apply outside pressure tactics. There’s only so much an outsider can do, because the bottom line is, the child is home with the mother. The father can stand outside in front of the house and demand, ‘We have an agreement,’ but no one can force the child to go with him. Of course, an alienating parent is going to try to take advantage, to be sneaky, to try to present to the outside that they’re doing it lishmah, for the protection of the child, and often they really believe it, and will certainly try to portray the fact that the other parent is to blame.”

The good news though, says Rabbi Viener, is that from his wide experience in family follow-up, despite the trauma and confusion, children who are products of alienation are often capable of marrying and building solid families, sometimes becoming even more sensitive to shalom bayis issues because of what they went through. “When the children mature and get the right hadrachah — if they are boys in yeshivah and develop good kesharim with their rebbis, or girls who develop good relationships with their mechanchos and get the right instruction and counseling — their young lives can get straightened out. Obviously it’s not always like that, but some of these stories do have positive endings, as is true with any victim of maltreatment and trauma.”

Is Trust Gone Forever?

That’s positive news for Moshe, another member of this frum men’s circle, who says his primary concern is the possibility of his own children forming future healthy relationships.

Moshe was married for 12 years, and while their marriage had always been challenging, when his wife decided the lifestyle they were living wasn’t for her anymore, she wanted major changes. She had new goals and views of how she defined herself, and being married and living an Orthodox lifestyle didn’t fit into that. According to Moshe, when she realized divorce was on the horizon, she began employing alienation tactics while still living in the same house.

“She sent out clear signals that I was a danger,” says Moshe. “She’d pull the children away if she noticed me talking to them. I’d always been a very hands-on father, driving them to school, helping with their homework, putting them to sleep. Basically, she started rewriting history that I’m a danger to the kids. She called Child Protection Services. She even called the FBI. The accusations were unfounded and no charges were ever pressed, but all that slander and badmouthing was in front of the kids, so they got very confused messages.”

After several years of what Moshe calls “nonstop alienation,” the courts finally awarded the ex-couple 50-50 custody, clearing Moshe of suspicion of abuse based on a court-ordered professional evaluator. “Look, except for some of the kids who choose not to come at times because of all the confusion, my children are with me now approximately half of the time — but the damage has been done. True, they’re with me, but they’re scared. They can’t trust me, they’re never really sure if I’m safe — I don’t know if they have the ability to trust anyone. They don’t know what’s true anymore, and that damage is irrevocable.”

Moshe says the most elusive thing about alienation is that it’s particularly hard to trace. On the one hand, an ex-spouse is set out to destroy the children’s trust in the other parent, while at the same time telling them, “Of course I want you to have a relationship with your Abba.” It’s a tricky manipulation, and Moshe tells of how one professional with extensive experience in parental alienation shed light on it by sharing with him a true account of a rosh yeshivah who came to his office, confused and broken.

This rosh yeshivah ran a school for bochurim who have one foot out the yeshivah door, yet one talmid, through his rebbi’s influence, became very serious and mainstreamed into a high-caliber yeshivah. This bochur was about to get engaged, and called the rosh yeshivah begging him to come to the l’chayim. “Rebbi,” he said, “you must come! You were responsible for changing my life.”

Meanwhile though, the father of the boy called the rosh yeshivah, ordering him not to show up. “If you come,” the father said, “the family of the girl will find out that the boy learned by you and they might break the shidduch!” The rosh yeshivah was torn — this was his beloved, prized student. But the father warned… maybe it was better for the bochur this way.

Later, the chassan called the rosh yeshivah back, telling him, “Rebbi, I can’t believe you missed my l’chayim — but you must be mesader kiddushin at my wedding. I’d be nowhere without you!”

When the father got wind of this, he called the rosh yeshivah and ordered him not to show up. “It will be a huge embarrassment for my son,” he said. “Aren’t you concerned for his welfare? Do not even come at the beginning of the wedding. Just show up at the end.”

Came time for the chuppah, and the rosh yeshivah was nowhere to be found. “What kind of a rebbi is this?” the father told his son. “He doesn’t come to the l’chayim, and doesn’t show up for siddur kiddushin — and he’s supposedly close to you? Luckily, there’s another rabbi here we can use.” By this time, the chassan was feeling confused and betrayed. The father meanwhile called the rosh yeshivah back, reminding him again not to arrive until they’d practically be sweeping up.

By the time the rosh yeshivah finally arrived toward the end of the wedding, the chassan practically fell on him. “Rebbi! Where have you been?! I don’t understand, you made such a difference in my life — the first person I told my kallah and her parents about was you! You didn’t come to the engagement, you missed the chuppah — I just don’t get it!”

The rosh yeshivah was beside himself with pain and confusion. He didn’t want to disregard the father’s directive and risk making a scene, but neither did he want to pit the son against his father, so he stayed away. But did he do the right thing? Some time later, when collecting money for his yeshivah, he made his regular stop at the father’s office but was met by a man who was livid and outraged. “You have the chutzpah to come here and ask for a donation, when my son begged you to come to the engagement and be mesader kiddushin, and you just disappeared on him?!”

“Why,” Moshe says, “did the professional share this incident with me? Because this is often how alienation works — it’s insidious, but you can’t trace it. The alienators make themselves out to be saviors, making a show of encouraging the relationship, telling the children, ‘Of course you should stay connected to Abba,’ while cutting him down at the same time.

“Look, I’m luckier than most — I’m back to seeing my kids. But you know, you can have them physically, but where are they emotionally when their mother is constantly feeding them a diet of vile hate and lies about me? Are they scared? Have they turned into people who don’t know how to trust? They’ll soon be moving into shidduchim — how will they ever be able to build trusting, safe relationships with their own spouses if they’re so damaged?”

The Best-Case Scenario

It’s a tough question, one that motivated researcher Dr. Amy Baker to write a book called Adult Children of Parental Alienation Syndrome, where she traced the lives of 40 adults who were victims of parental alienation as children, men and women who were turned against a parent as children and how they eventually came to terms with it.

“Being a child victim of parental alienation can warp a child’s thoughts and feelings toward the targeted parent, but that does not mean that the child will be damaged for life,” Dr. Baker tells Mishpacha. “Parental alienation is an adverse childhood experience that is extremely damaging to the child’s sense of self, but that said, through appropriate treatment and support, the child victim can grow to have healthy relationships.”

She tells the stories of ordinary people, struggling into their adult years with the damage they describe from having been manipulated into hating a parent. One surprise from her research was that, contrary to earlier research pointing to alienation as manipulation by mothers to punish fathers, mothers and fathers are about equally likely to do the manipulating. Yet as hopeful as she is about the possibility of healing, many sad patterns emerged: 58 percent were themselves divorced, 70 percent suffered depression, 35 percent developed problems with drugs and alcohol, and 50 percent of those with children were estranged from their own children. There is also a lot of self-hate, largely due to the guilt they feel once they finally have an inkling to how badly they treated the targeted parent.

One of those young men, today married with a family of his own, told of how his tough, alcoholic dad bullied his mother — a quiet, simple woman — to give up custody. His father told him his mother abandoned him, that she no longer wanted him, and that she was basically an awful person. He said that he renewed a relationship with his mom when he was in his twenties, but his dad’s brainwashing was so strong that he could never fully love her. Years of therapy, and marrying a good wife, helped him reconnect with his mother’s love, but by that time, she’d already died.

In the frum world, alienation often takes the form of piety — one parent pulling the child away from a relationship with the other parent because of a disparity in religious devotion. Dovie, today a building contractor in Louisiana who’s no longer religious, was sandwiched in the middle of such a dispute after his parents divorced when he was six. The family was living in Bnei Brak at the time of an extremely acrimonious divorce, and Dovie’s mother — with the backing of her family who were considered well-heeled with prominent yichus — separated the children from their father by whisking them back to the US and cutting off all contact. His mother’s family claimed her ex-husband was unsafe; Dovie, looking back through the eyes of a Yiddish-speaking cheder kid with tzitzis and peyos, says he believes his mother was convinced that her children having contact with their father would lead to their religious downfall because the level of his religious devotion wasn’t on par with her family’s. But the irony, says Dovie, is that because of the alienation trauma and subsequent confusion over religious priorities, today Dovie and two of his sisters have nothing to do with Yiddishkeit.

Dovie’s father eventually traveled back to the States and reestablished a tenuous relationship with some of his children — Dovie even lived with him for a while as a teenager after he was thrown out of yeshivah, and today they have a warm connection.

Dovie concedes that maybe his issue wasn’t so much about rejection of Torah per se but about the associated dysfunctional behavior of his own family, which took such an emotional toll that he left the frum world behind. “For years, I was miserably depressed and suicidal,” he admits. “I would cry all night, I couldn’t find myself. Because it turns out that when you’re raised in a frum environment, your entire foundation for life, your goals, your principles, your morals, are all about Yiddishkeit, and when that’s gone, you have no anchor, nothing.”

Still, it was too emotionally wrenching for him to go back. “It’s been a long ride for me, but I can’t live that life again — reliving the misery of being ping-ponged for the sake of religion. But I do feel bad for my mom, who I try to have a decent relationship with today. She pulled us away in order to keep us frum, and today we’re on the other side. I’m sure it’s killing her. But that’s what happens when you ignore the human reality of the kids involved.”

Healthier Interactions

Is there a way of improving the odds of these children being able to function in healthy relationships? While alienated children can be doomed to a life of dysfunction in their adult relationships, as well as for increased risk for depression, suicide, anxiety, excessive anger, low self-esteem, and addictions, it is possible for them to turn around, according to Denver-based psychologist Dr. Susan Heitler, a Jewish family reconciliation expert and author of The Power of Two: Secrets to a Strong and Loving Marriage. Dr. Heitler, who has worked extensively with alienated families in her clinical practice, believes that a course of family and individual therapy specifically from a therapist knowledgeable about alienation — because alienation has a very tricky and often inscrutable presentation — can help a child learn ways to respond to the alienating parent that keeps him/her safe, and can learn healthier interaction habits than what the alienating parent has modeled. “That means learning strategies that will teach them how to exit situations in which they are becoming angry, to learn to listen to others rather than only to what they themselves want, and to resolve differences in collaborative, win-win ways,” she told Mishpacha.

Dr. Heitler says she’s seen children of alienation come back to the “enemy” parent once they grow up, and the best odds of that happening are when there is some kind of early intervention. “Once the alienation has progressed, ‘reunification therapy’ can sometimes work to reintegrate the child into the targeted parent’s home,” she explains, “provided the therapist early on brings the child and the targeted parent together in a way that lets them re-experience having fun together, and then only gradually addresses the lies about that parent that they’ve been led to believe. It’s unlikely, though, to be able to bring the parents back to any kind of cooperative relationship. In the cases I’ve handled which have been relatively extreme, neither parent wants anything more to do with the other. The best you can generally hope for is that the child is able to again have a positive relationship with the alienated parent, who is generally also the emotionally healthier parent.”

When one parent claims alienation and the other parent contends that it’s simply the children who no longer want a connection, is there a way to come to move forward? According to Rabbi Moishe Blum, the Siksa Rebbe in Monsey and head of a busy New York beis din that deals with all types of arbitration, it’s often a personality question. “If the mother has a borderline personality disorder, is narcissistic, or has some other personality dysfunction, I tell the father, ‘You can forget about the kids for now. Don’t even fight. Wait till they get older, and eventually they’ll come back to you.’ ”

But Rabbi Blum, who has been dealing with gittin, shalom bayis, and family fallout for the past 27 years, says these scenarios are the extreme cases. The more common ones are what he calls the grey area, when both parents are flawed, albeit not wholly dysfunctional. In these cases, he’s found that often the alienated, targeted parent who isn’t seeing his/her children unwittingly plays a part in the tragedy as well. The alienated parent, he says, has to do a reality check: Is he somehow giving off vibes that make the child uncomfortable?

“Look, with alienation it’s often very hard to figure out the truth, but one thing I can tell you — not to justify this mean, vicious behavior, but to explain it: A child will naturally cling to the mother,” says Rabbi Blum, “and if the father is overbearing or critical or has a difficult personality, or is giving mixed signals about the mother’s competence, he might think he’s intensifying his own relationship with his kids, but really he’s pushing them away — this is because the children aren’t equipped to handle the conflicting, painful, and confusing emotions in this tug-of-war of dual loyalty. It could be that the mother is manipulating this, but at times that manipulation only works if there is something about the father as well that contributes to the conflict — but it’s hard to pinpoint, and the targeted parent usually doesn’t see his own chelek in the dynamic.”

No Giving Up

The main irony of parental alienation is that for all the therapists and askanim who want to help ease the plight of children after divorce, most do-gooders are not equipped to spot it because it’s so counterintuitive, according to Dr. Steven Miller, who served for 30 years as a clinical instructor in medicine at Harvard Medical School and is currently a consultant in behavioral and forensic medicine, with a professional focus on parental alienation and other types of pathological alignment.

In testimony before a legislative task force investigating the family court system, Dr. Miller explained why so many people don’t “get” alienation. First of all, he said, alienating parents tend to present well with the four C’s — they’re usually cool, calm, charming, and convincing. That’s because effective alienators tend to be master manipulators who are highly skilled at managing impressions, especially initial impressions. These traits are usually related to an underlying personality disorder, typically of the borderline, narcissistic, and/or sociopathic types.

In contrast, he said, targeted parents tend to present with the four A’s. They are anxious, agitated, angry, and afraid. That is because they’re trauma victims. They are attempting to manage a horrific family crisis, usually without success, often while being attacked by professionals who fail to recognize the counterintuitive issues. Indeed, non-specialists often get these cases backward— they conclude that the alienating parent is the more competent parent, and that’s likely to be a catastrophic error in custody decisions. Even in the face of abuse, Dr. Miller stressed, children rarely reject a parent unless there is a powerful alienating influence. And they will never reject a non-abusive parent unless they are induced to do so by a third party — kids are genetically wired to cling to their parents.

Furthermore, said Dr. Miller, clinicians who don’t specialize in this area often mistake pathological enmeshment for healthy bonding. To a non-expert it looks exactly like a warm, close, loving, healthy relationship. From their perspective, the parent and the child are close, and the enmeshed parent displays great empathy for the child. “In fact,” said Dr. Miller, “enmeshment is anything but healthy — it’s a potentially life-threatening psychiatric emergency, representing a cascade of severe boundary violations and is the extreme opposite of empathy.”

So what is the agitated, anxious, afraid parent to do as he/she navigates the devastation of losing a child’s relationship? Dr. Baker, from her experience, says that as hard as it is, don’t give up. “Have some contact every week, every month, something. Text them, send them a gift, send a card — even if you know for sure that the kid is ripping up your card and spitting on it and throwing it out.” Because, she explains, once the parent stops sending the card and stops reaching out, then the alienating parent turns to him and says, “See, your dad is a bum. He never writes you.” And the child says, “Yeah, you’re right. He never writes. He doesn’t care about me.”

But it’s easier said than done, according to Baruch. “Look, I haven’t given up hope for a relationship with my daughters, but in order to preserve my sanity, I’ve stopped actively pursuing it. You can’t constantly have the rejection on a regular basis and still be a functional human being. So I’ve had to shut down, because the emotions are too much to handle, too overwhelming when I stop to think about it. How did it happen that my kids got cut off? I’ve been their father since they were born. What kind of crime fits the punishment of being cut off from your own children?”

Note: Due to legal and family sensitivities, all names and identifying details of parents and children have been changed. Interviewees may be contacted through the Mishpacha office.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 749)

Oops! We could not locate your form.