Out of Beat

| May 4, 2021

I was in the mall the first time it happened. I began to feel lightheaded and faint. I looked for a place to sit down, while questions swirled around my brain. Was I having a panic attack? Was it because I was pregnant? Maybe I was dehydrated? I took a drink of water, but the sensation didn’t let up. Twenty minutes later, I finally felt better enough to get up, get in my car, and drive home.

In the car, I thought about what I’d experienced. As a social worker, and someone with a generally more anxious personality, I wondered if the sensations I’d had were related to some sort of anxiety or panic disorder.

I experienced this sensation a few more times over the next few years, but it always seemed to resolve quickly before I could really put a finger on what was going on. Also, as a busy mother, I didn’t have too much time to dwell on what was happening.

Six years after the first incident, shortly after moving to a new community, things began to escalate. Our family was eating Shabbos lunch at a friend’s home when suddenly, right after Kiddush, I started feeling faint and lightheaded again.

Heart pounding, I excused myself to the restroom and took some deep breaths, but nothing seemed to help. I began to panic. Was there something wrong with me? Why did this keep happening? After what seemed like an eternity, I began to feel better and returned to the meal.

The episodes began to become more frequent: In the library, in the grocery store, even while driving — and always out of the blue. Unpredictable in both coming and going, they usually didn’t last long, but always left me feeling rattled and confused.

As time went on, the episodes began to get longer and more intense. Shortly after my third son was born, we traveled to visit our families in Baltimore for Pesach. We were visiting friends when, all of a sudden, that all-too-familiar sensation returned. This time, though, I really did panic. Waiting it out wasn’t working anymore. We called Hatzalah, who came in just a few minutes. However, by the time they arrived, the sensation was once again waning, leaving me feeling as frustrated as ever. I remember lying in the Hatzalah ambulance being told that the tests were normal, but feeling deep down that something was seriously wrong.

I reached out to my physician about my symptoms. She wasn’t sure what was causing them, but suspected it may be a heart issue. She ordered a heart monitor for me so that I could track my heart rate at baseline and see when it began “malfunctioning.” I was supposed to attach the monitor to my chest, and it would send a baseline reading of my heart rate to the company that produced the monitor.

However, since I was only having heart issues once every few months, I didn’t feel like it made sense to wear the bulky monitor under my clothing all the time. I figured I would keep it at home, and if I experienced that same sensation, I would quickly attach it and get the reading. Of course, once I had the monitor, it never happened, so the whole plan ended up being a waste of time and money.

My husband (who’s in the medical field himself) encouraged me to see a specialist who could figure out if what I had was really a cardiac issue. We consulted with a cardiologist who took an EKG. He said it looked normal to him, but decided to consult with the electrophysiologist, a cardiologist whose speciality is reading EKGs. The second doctor noticed a small irregularity in the way my heart was beating and diagnosed me with an supraventricular tachycardia (SVT). An SVT is an irregular or fast heartbeat. At the time, I was pregnant, so he encouraged me to take a “wait and see” approach.

I called him prior to giving birth, and he said that the SVT shouldn’t impact at all on my delivery, but told me to be in touch if it was affecting my functioning at all afterward. He encouraged me to “bear down” (push my muscles downward) when I experienced an irregular heartbeat starting, in order to stop the cycle.

But a few months later, I returned to Baltimore again for a day trip. I took an early morning train with the intention of returning home later that evening. My mother picked me up from the station, and on our way home, it started again. This was the worst episode yet. I tried to reassure my mother and myself that I’d be fine — after all, the sensation always went away on its own. After 30 minutes, though, we couldn’t wait any longer. Once again, we called Hatzalah. This time the EKG showed that my heart rate was incredibly high. I was told that letting my heart run like that for so long was dangerous. The Hatzalah members carefully placed IVs in both of my arms and transported me to the nearest hospital.

I was placed in a hospital room relatively quickly. I remember a very unhelpful resident came in and started talking to me about stress and how it was possible stress was contributing to my condition.

She joked, “Maybe you’re allergic to Baltimore, since you keep having this response when you come to visit.”

I didn’t tell her we were planning on moving back here in three months! The doctors in the ER ran some tests. My mother stayed with me, and my sister, a nurse in the same hospital, came to check on me occasionally. At least this happened while I was in Baltimore with my mother, I thought to myself, instead of when I was by myself, or worse, alone with my kids.

I left the hospital and returned home, determined to finally address the issue. I scheduled another appointment with the cardiologist and explained that the “wait and see” approach wasn’t working for me, and that I wanted to deal with the problem head on. He advised me to get an ablation, a procedure where they destroy the tissue in the heart that is sustaining the abnormal rhythm.

Initially, I was very concerned about undergoing a procedure — something that I’d never had to do before, baruch Hashem. However, the alternative scared me as well. I was worried about the episodes reoccuring at a time where I was alone with my kids.

We scheduled the ablation for a few weeks later, and our families came down to help with our children and offer support. On the day of the surgery, I waited to be placed in a room and then prepped for the surgery. The doctors threaded a catheter up through my leg to my heart. Once inside, they tried to recreate the faulty rhythm. (After the procedure, they try to induce the faulty rhythm again. If they can’t, they know the procedure was effective.) The whole thing was very scary for me, but I felt that I was in good hands with caring, competent professionals.

When I went into the operating room, I was all by myself, since my husband wasn’t allowed to accompany me. It was a very intense moment as I realized the only one who I could rely on at that point was Hashem. I put my life in His Hands (something usually very hard for me to do!) and promptly fell asleep, feeling as if He was holding me. I woke up, very groggy and uncomfortable, but happy to be over this hurdle.

I was back in the hospital room where I’d been prepped. It took a little while until I felt better, and then I had to practice walking up and down the hospital hallway with a very kind nurse before I was sent home (where I arrived just before dinner). The recovery period was thankfully just a few days long, but I was told not to lift anything heavy during that time, including my infant son, so I did need family around to help me. I had a small scar where the surgeon had made an incision in my leg, but that went away with time, too.

Later, I learned that when the surgeons went in to do the procedure, they saw my heart was already beating much more quickly than normal, even though I didn’t feel anything abnormal that day. They explained that it was very likely I was experiencing an increased heart rate a lot more often that I thought — I just didn’t notice it until it was really extreme. After they shared this with me, I remembered that there were times in the past year where I’d just felt anxious all of a sudden, for no reason. I would be outside with my children biking around the block and would suddenly experience a feeling of anxiety or faster-than-normal heart rate. It was all starting to make sense.

I also learned that it isn’t uncommon for people, especially those who have more anxious personalities, to be mistakenly diagnosed with an anxiety or panic disorder when they really have an SVT. Some people go for years without appropriate treatment. (One woman in my community was put on strong anti-anxiety medicine for years for her “panic attacks” that were really caused by an SVT.) I know I was lucky to have a husband who encouraged me to see a cardiologist and identify what was really going on.

While I, like many others, have had some negative experiences with medical professionals in the past (especially about issues that are less clear cut), this experience showed me the positive side of the medical field. Despite it taking a while to get a diagnosis, once we did, we were able to receive great care from the volunteers (Hatzalah!) and medical professionals that we met along the way, who were for the most part incredibly responsive and caring.

Science, like the field of medicine, often gets a bad rap these days. However, after my procedure, I felt incredibly grateful for the scientists who worked to develop a procedure that makes it 95 percent likely that I’ll never experience a heart issue again.

Above all, I’m especially thankful to Hashem for holding my hand throughout the whole process and helping me feel taken care of by Him and His messengers.

What is SVT?

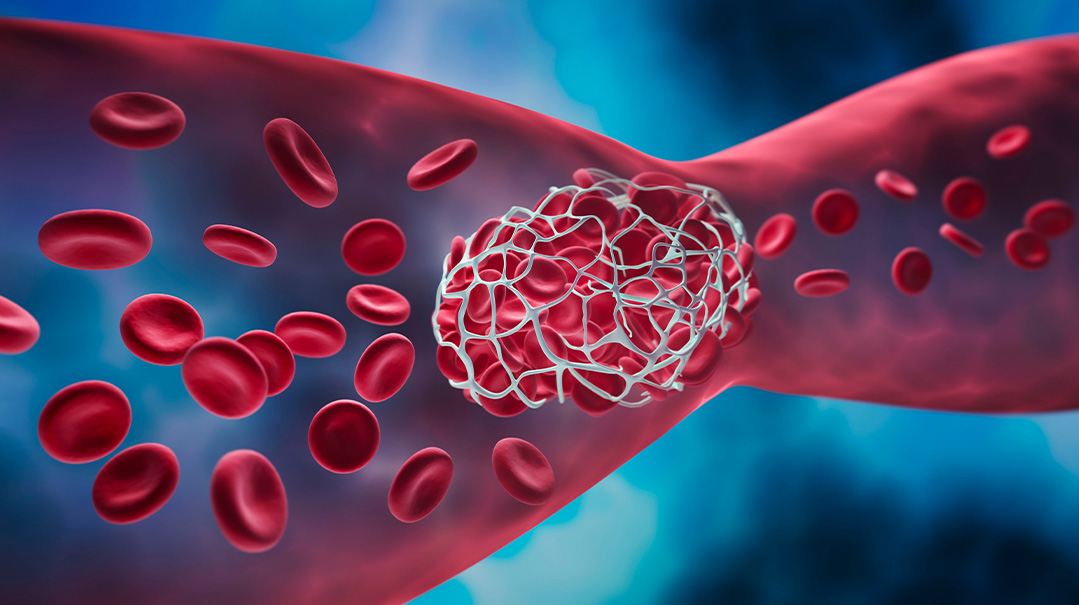

The term supraventricular tachycardia (SVT) describes a group of unusually fast heartbeats that occur when the electrical impulses that coordinate heartbeats aren’t working properly. Supraventricular means that the electrical activity originates above the ventricles, in the atria or AV node of the heart. Tachycardia refers to a heart rate that is higher than the normal rate (between 60 and 100 beats per minute).

Most often, SVT happens when a person is born with an “extra” area of heart tissue that has electrical conduction. Even so, SVT doesn’t always occur, but it can be triggered by many different things, including stress, lack of sleep, or physical activity. Other triggers can include heart failure, thyroid disease, heart disease, and chronic lung disease; smoking, alcohol, caffeine, or drug use; or certain medications, including asthma medications and over-the-counter cold and allergy medications.

When the heart beats too fast, you can feel palpitations or fluttering in the chest, shortness of breath, sweating, or a pounding sensation in the neck. The quick heartbeat can also lead to the heart not filling properly, which, in turn, can cause the brain to not receive enough blood, resulting in lightheadedness, dizziness, or even fainting (syncope). SVT symptoms can occur suddenly and last from a few minutes to a few days. However, some people don’t have any symptoms at all. If the episodes are frequent or a person has another medical condition (such as a heart condition), it can be more serious.

SVTs are the most common type of arrhythmia in infants and children. It occurs twice as often in women, especially pregnant women. The majority of people with this condition only experience rare episodes, and don’t need interventions of any sort. However, over time, untreated frequent SVT episodes can weaken the heart and lead to heart failure, especially if a person has other coexisting medical conditions.

(Originally featured in Family First, Issue 741)

Oops! We could not locate your form.