No Need for Knives

Davey’s eyes flicker to my right sleeve and I narrow my eyes as he vacillates over my fate. Is there anything left of me, or have I been reduced to a cripple?

“S

et the forks, Lou.”

My mother opens the drawer on her way to the oven, pulls it hard enough for the cutlery to clatter loudly. Ma loves emphasis.

“Right,” I mumble in response. The word comes out corroded, as if I’ve just woken up.

Hannah comes into the kitchen, wrinkles her nose at the sight of the mashed potato-meatloaf amalgamation cooling on the counter. “Where’ve you been?” she asks me.

I shrug, nod toward the open drawer. “Set the forks.”

As I head into the dining room I hear her mutter, “Just forks.”

Something close to laughter wells up inside of me and I spin around, searching her face to see if I’d heard correctly. That’s the thing with hermit life; there’s a lot of doubt, on account of the whispers trickling down the walls, murmuring from the furniture, whole conversations from the trees outside my window. These days I can’t trust myself to differentiate between wishful thinking and actual sound. I’ve lost my bearings. Fourteen years old, and I can’t find my bearings, nor do I know what bearings are exactly, but my grandfather used to say that before his brain melted into mush, and I think that’s about where I am right now. Bearing-less. Pre-mush brain.

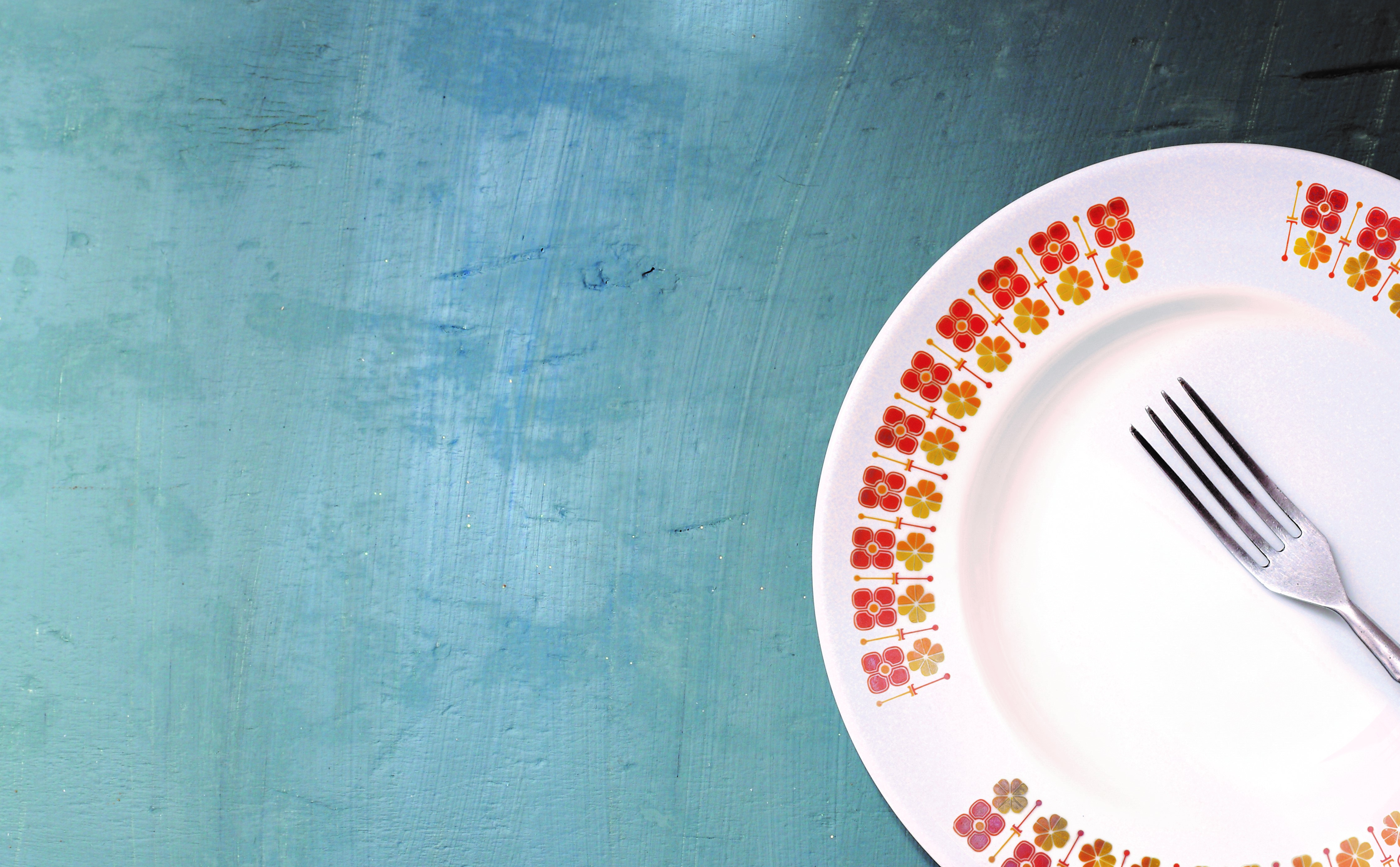

If she’d said it, if she mentioned the forks, there’s no sign of it now. No conspiring snicker. No eye roll or stifled laughter. I’m disappointed because when you get down to it, I know the spoons will return in the fall with the arrival of soup. But it seems the knives have experienced the worst sort of death; the completely overlooked kind. Unmentioned. Unannounced. Not even celebrated. Sudden and swift with no memorial at all. The cutlery drawer is a tomb. Here lies the humble dinner knife. Forever.

“You don’t know where you’ve been?” Hannah asks me then, hands on her hips as if she’s older than me.

I feel the muscles in my throat working, the cogs in my head buckling under the pressure of formulating an answer. Rereading my stash of Fantastic Four. Swatting at gnats who’d found their way through my window. Listening to cicadas screech from the backyard oaks. Horizontal. All day. Watching the trees turn a deep auburn, my head on the wooden floorboards, throwing my softball at the ceiling, catching it. Barehanded. One-handed. Nowhere, doing nothing, while the last days of summer go sliding through all five of my fingers.

I shrug again and Hannah lets up when she notices Ma’s lip curl under her top teeth. The last thing we want is more tears.

The front door slams shut, which means the worst part of the day is about to begin. The summer of 1963 is when I find out that guilt has a stench. There is a cloud of putrid stink that follows my father from room to room, resting on his newly hunched shoulders.

Every night since I returned from the hospital nearly two months ago without my right arm, he enters the house wearing the same grim face. Then we play the same old game, with the same old rules. Ma calls “Dinner!” just like that, the “er” part going down a notch for emphasis. We all sit down and try not to stare at the place where the knives used to reside before their untimely death. My father’s eyes begin to sweat then, on account of the exercise I assume, darting around this way and that.

He sits to my right, at the head. Ma pours him a drink.

Between his scotch and my heart lies the canyon where my arm once lived. It reeks of blood and twisted metal. All through the meal his eyes skitter away, frantically dodging a head-on collision with guilt.

It’s a game of make-believe, the whole affair, an upside-down funeral where we scoop baby food into our mouths through tight, fake smiles, pretending we aren’t all pining for missing things. Steak. Limbs.

The avoidance is because I’m supposed to be recuperating now. So better not to talk about unpleasantness, see. The guilt is because of the fighting that happened immediately before the accident. He wanted me to buckle down. That’s how he’d said it — no more ball games, he’d threatened, if my grades didn’t improve. Sitting in the passenger seat of his Edsel, I told him I didn’t see much of a point in grades and anyway, I was seriously considering ending my high school career at 16. That made the veins in his head pop out and his neck flush a deep red and then, well, I don’t remember much of anything after that. But in a way, we both got what we wanted. He got the end of my ball playing. I got to slack off for the remaining month of ninth grade. I also got a transhumeral amputation, which means my arm was sliced off clean above the elbow.

“They’re saying there may be as many as 75,000 people at this march on Washington. Just imagine that.” Ma’s job is to make conversation so we all survive dinner hour. She takes this job very seriously by reading the morning paper religiously for fodder.

My father’s eyes jump to the glop, then to the peas, steal a sideways glance in my direction, then run away again.

“Seventy-five thousand people who feel the pain of the blacks, can you imagine? That’s a lot of people.”

My father picks up his napkin, blots his mouth. “I imagine many of them will be blacks themselves, Cheryl.”

She thinks about this for a moment, then moves to local news.

“I ran into Mrs. Brum at the dry cleaners. She said Davey would love to see you.” This is met with a thick silence where we all focus on our plates until Ma moves on to household affairs. She’s got a system. “I’ve taken down some of your school shirts from last year, Lou. Try them on, see if they fit. We’ll head down to Penny’s for shoes next week.”

Saddle shoes and corduroy pants and people. The thought makes my palm sweat.

“Shoes fit. Don’t need new ones.” The lie tumbles out. Everyone turns to look at me. That’s another thing about hermit life — when I pipe up, people listen.

Ma’s lips pinch up, all tight and puckered. I scoop up the last of the coleslaw, swallow hard, clear my plate. Then, with the daily dinner debacle blessedly over, I head upstairs. Ma doesn’t ask me to do the dishes anymore. She assumes my maneuvering the sponge-plate duo will result in my spontaneous combustion. Much like the knife-fork duo.

I climb the staircase, Hannah right behind me. At the top of the stairs I see that the ladder to the crawl space is down. Last year’s turtlenecks are hanging from the top rung. They reek of mothballs and football and knit gloves and dirty snowbanks and a toad set loose in the locker room and the feeling of being freezing cold and dripping with sweat all at once.

I stare at the shirts. Hannah is next to me, staring at them as well, and I know she wants to say something, I can almost feel the words welling up inside of her and then the hiss of defeat as she gives up and moves toward her room.

“Forks,” I say too loudly. I go red as she turns around to face me.

“It’s just forks… every night,” I stammer.

She tilts her head to the side, puzzled. Then her features soften and she gives me a quick, pitying nod. A nod you’d give someone who’s lost his brain, accompanied by a smile you’d give someone who never had one in the first place. A swift gesture reserved for people you’d rather avoid in the street on account of the muttering and missing parts. Deranged, then. That’s where I am. Deranged. Last year we caught toads by the river and you kept slipping on the rocks like a baby. Don’t look at me like I’m an imbecile. I’m two years older than you. I want to yell but she’s already escaped to her room.

I punch the closest turtleneck. The empty sleeves quiver and dance, flappy and limp. The sight makes the bile rise from my stomach.

I will never be on a team again. That’s the thought that smothers me to sleep, softball in hand.

I dream about the complexity of shoelaces. How they seem so simple, until you try to tie them one-handed.

***

I’m on my back, as usual, pressed against the wooden floor of my room, locked in a game of catch with the ceiling. My skills have improved over the past two months. Shortly after returning home from the hospital, I’d come downstairs every morning with a fresh black shiner around my eye, much to Ma’s horror. These days, I hardly miss.

“Lou.” Ma knocks and opens the door.

I grunt in response.

“I’m out of eggs.”

The sentence sounds stiff and starched, like she ironed out each letter, then practiced her speech in the mirror.

I toss up the ball, catch it, toss it up again.

“Lou.”

“What?”

“Eggs.”

She doesn’t need eggs. The egg man was here two days ago. I remember because I watched him from the window and noticed that his boots had no laces.

She doesn’t need eggs, and she knows that I know she doesn’t need eggs.

“Send Hannah.”

“She’s at Sherry’s.”

They’d thought this out, then. Planned it. And not the first time, either. A few weeks before it had been sugar. The way she’d said it left no room for argument and I rode my Stingray to the grocery as fast as humanly possible. There I was met with a whole store full of pinball eyes, a few outright stares, and one comment from a man from the synagogue who smelled like sauerkraut.

“My, Lou! How tall you’ve become!” he’d said with a wobbly, sweaty-lipped smile.

A part of me wished someone would just say. “My, Lou! You’ve lost an arm!” and get it over with. On my way home I’d passed a mother pushing her daughter on an old tire swing hanging from a tree on the lawn. They were laughing until they spotted me. Then their smiles slid to the floor and were promptly replaced with horror. I’d felt bad, ruining their day like that, they’d seemed nice. Ma baked a pound cake when I got home. To celebrate.

“You’ll go to Branford’s. Not the grocery. Grocer’s out of eggs. I phoned.”

A coup, then. I keep at my solitary game of catch while my intestines shiver, twisting themselves into a knot.

“All the way to the farm?” I turn to look at her just as the ball comes down with a crack, missing my face by an inch. Ma lets out a yelp.

“Goodness, Lou! You could crack your skull! That’s just what you need, another injury, Heaven forbid it.”

I cut her off. “I’m not goin’.”

She takes a deep breath and from the corner of my eye I notice her clenched fists. A cyclone of unsaid words comes up between us. School’s starting next week. School’s starting and you haven’t let a single friend in to see you. You’ve barely seen a soul since the accident. She glances at the gigantic contraption in the corner of my room and I answer her without saying a word. I won’t wear the prosthetic because it’s unbearable and you know it. I hate you for letting me lie here, turning to jelly. Please don’t make me leave. Please, please—

“Louis.” Her voice is all rickety. “I need you to get up.” Then she stamps her slipper-clad foot on the wooden floor. “This. Minute. Get up. Get up! Stick some shoes on those feet and go.” She is yelling in a whisper, which is the scariest sort of yelling there is. Before I know what’s happening she reaches down, grabs my softball and throws it straight out the open window. Overhand. “Go buy me some eggs.” Her eyes are wild, and her body is shaking something fierce which scares me enough.

“All right,” I say, standing up quickly. “I’ll go, I’ll go.”

“Thank you,” she says after a pause. Golly, she’s crying again.

***

I grab my bike from the bottom of the stairs to the cellar, then realize with a sick feeling that I’ve gotta go on foot; no way to hold the eggs and the handlebar both with just one hand.

It had stormed earlier in the day and the world around me is still wringing out. Propeller seeds are spinning through the street, dropping kamikaze-style from the canopy of tree branches above me.

My gym shoes are soundless except for the click of one renegade lace hitting the pavement. I’ve got limits — asking Ma to fasten my All Stars is a line I won’t cross. I bend down and stuff the lace back under the tongue, feeling oddly exposed. These streets are as familiar as the freckles on my nose; it’s me who’s morphed into something unrecognizable. My room has grown around the absence of my arm the way dandelions overtook the spaces in the garden where my grandfather once stood with a watering can. Time has a way of filling emptiness with weeds, brightly colored nuisances that quell the pain of missing things. But I’ve spent no time on the street since that night. Time has yet to work its wonders out here, I’m still raw enough to feel the pain clawing at my throat. It sends pinpricks to the corners of my eyes where moisture seems to gather whether I like it or not.

A curtain moves in the window across the street. I kick a pebble, send it hurtling. My world has been stolen. The familiar little town with the familiar faces has turned on me. The gawking has filched my right to blend in, which is all a pimple-faced fourteen-year-old boy really wants anyway.

“Louie, is that you?” Our next-door neighbor Mrs. Littler comes out from the side of the house in a sun hat, rake in hand, her saggy jowls jiggling as she speaks. “Well, look at you, sugar snap! Hidin’ in the dark all summer with the mushrooms.” She looks me up and down. “You must’ve grown three inches.”

“Yes, ma’am.”

“Blueberries are in. You tell Hannah to come over and help me with the picking tomorrow.”

“Yes, ma’am.”

“Lou.”

“Hmm.”

She looks pointedly at my empty sleeve. “Glad to see you’re well.”

I nod at that, then continue walking, my heart moving like a drum in my chest. Was I well? I hadn’t thought so. I look back, past my house, toward the swell of trees.

I could run.

The town is encircled by dense forest, as if long ago a chunk of trees had been raised out with an ice cream scoop and a town plopped down in their place.

I could be gone for a long time.

It’s the sudden image of missing-child signs taped to pock-marked telephone poles that propels me forward. Missing: Boy. One Arm.

I bypass Main Street, naturally, take the backroads up toward the farmlands. The problem with going up to Branford’s farm is that my gang uses one of Old Man Branford’s fallow fields for softball. I’ll have to pass the lot on my way to the market where his wife sells produce. At 4:30 the place will be crawling with boys, jaws hanging wide open when they see me. The brainless ones might even call me by my nickname.

A few weeks before the accident Sandy Koufax pitched a no-hitter against the Giants. The four of us — Perkins, Teddy Wilcox, Fitz, and me — listened in, sprawled out on my bedroom floor, adjusting the transistor radio this way and that. After the game, the gang had taken to calling me Koufax on account of me being Jewish and the best pitcher in town. Secretly I liked it, but always corrected them by saying that I pitched right-handed.

Now I’m one-handed.

Wrong-handed.

The road up to the field brings back memories and each one is a shock to my system.

The night it happened we’d ignored the flicker and groan of the streetlamps, kept on playing while the dark ushered in the crickets. We inhaled the night so deeply that the specks of dust became dancing slivers of glass in the moonlight. We were intoxicated by the fine weather and the fact that it was almost real summer and that we were almost real adults, and all those almosts set our feet on fire.

I’d been on the pitcher’s mound, as usual.

Fitz was on first, Perkins was playing centerfield (he likes to think of himself as The Mick). Then my father pulled up in the Edsel. “A school night,” he’d called out, and I’d ripped a newborn bunch of honeysuckle off the fence, then climbed into the car humiliated, the embers of our minor rebellion smoldering as he scolded me. We fought then, the same silly fight about school and ball playing and rules, while I squeezed the pus out of the honeysuckle. That was the last thing I did with my right hand. Killed a flower.

I’m almost at the lot now and I know I’m a sight. Pasty white, on account of hermit life, wearing too-short shorts, missing the most important part of myself. I can already smell the honeysuckle that climbs the fence of the lot, now old, tired, and mostly gone. Its stink turns my stomach.

Perkins came by a few times. I’d made my mother turn him away at the door, feigned sleep or pain, whatever it took, then watched him from the window, running away like a schoolgirl. His ma had forced him come; that much I knew.

The only one who’d kept trying was Davey. Four-eyed Davey Brum. Not even a best pal.

I nearly vomit on the side of the road as the chain-link fence that surrounds the field comes into view. It’s broken in places, leaning in others, full of holes and prickly wire. I strategize for a minute and decide that faster is better. The field lies to the left of the road, which works in my favor. I’ll just keep walking, no matter what.

Someone’s popped it up and there’s a mad scramble for the ball. It’s Fitz who notices me first.

“There’s Koufax!” He runs toward the fence and I see the whole field turn to stare. “Hiya, Lou!”

My saliva turns to sand and my brain goes feathery white, leaving me with no choice but to mindlessly stick to the plan and keep on walking. The gang ambles toward the fence, a few of them call out my name, most of them just hook their fingers over the holes and stare hard. I give an awkward little wave while shame floods my face and creeps to the top of my head and everything around me goes swimming. I’m a sweaty mess by the time I round the corner. I rest my back against a wide sugar maple, breathing hard. That’s when I hear footsteps and notice Davey is following me.

Davey.

Davey’s a High Holiday friend. One of the boys I hang around the synagogue with because he’s my age; a friendship born out of dire necessity, not choice. During the long services Davey and I would make frequent trips outside, leaning against the ivy in the synagogue’s courtyard, kicking a pebble between us. Back at school Davey would cling to me for a while, all through October in fact, hoping the synagogue friendship would carry over.

It never did.

Davey’s pollen allergy keeps him indoors until late summer; he usually makes his appearance at Branford’s field long after the rest of us have turned brown from the sun. Not that I think the extra weeks of practice would help him; he’s a hopeless ball player.

“Hi, there, Lou!” Davey calls. “I came around your house a few times.”

“I know.” I answer curtly, walking up the lane toward the market.

“Your ma said you weren’t up for visitors.”

“I’m not.”

Davey doesn’t seem to be bothered by this.

“I’m real sorry about your arm,” he says from behind me, trying to keep pace.

I wince.

The farmer’s market is nothing more than a refurbished barn. A few people are hovering over a wooden crate of plums. Mrs. Branford barely glances in my direction when I ask her for a dozen eggs. She hands over the tray perfunctorily and our transaction is so completely devoid of any reaction on her part that I wonder if she’s sleeping. I’ve heard some people can sleep with their eyes open.

Davey’s waiting outside the barn, hands deep in his pockets. I walk past him quickly.

“Heard you’re gonna be startin’ school with us. That true?”

“I guess.”

“Does it hurt bad?” he asks, after a beat. “Your arm?”

“No.”

He’s like a battering ram with a postnasal drip. I walk faster down the path and through a thicket of trees.

“Go away, Davey,” I mumble.

“Had to be your right arm, too. For a pitcher and all. It’s too bad.”

Too bad? Is that what this is?

The grief I’ve been feeding all summer rears its head. It’s a monster of epic proportions now, having grown wild while I wallowed on my bedroom floor. Too big to rein in now. Too huge to deal with.

“You gonna wear a fake arm to school?” Davey calls out.

The trees widen out around me, sucking in their breath.

I spin around, ready to give Davey a piece of my mind, just as my left shoe pins down the lace of my right one. I lose my balance and the tray of eggs tumbles out of my hand, lands with a delicate snap on the mossy earth in front of me. Davey stops short.

We stand there staring at the mess in silence until Davey lets out a low whistle. I slide to the ground to sit among the brokenness. It would be kind if the mud would take me. I could just disappear beneath the earth. I wouldn’t have to walk back past the field. Wouldn’t have to enter the reeking guilt-house empty-handed.

“Get up, pal.” Davey’s voice has changed, the edges of his words drip with pity. Something ugly billows up from my stomach.

“Come on. I’ll go buy more eggs for your ma. Get up.”

My hand darts out, a reflex from a bygone era, and I grab an egg that survived the crash. I throw it as hard as I can, nailing Davey in the stomach. He goes bug-eyed, stares down in disbelief at the yoke dripping down his shirt.

While Davey bends toward the tray, I stand up. He straightens and then there is a moment of hesitation that tells the story I’ve been hiding from. Davey’s eyes flicker to my right sleeve and I narrow my eyes as he vacillates over my fate. Is there anything left of me, or have I been reduced to a cripple? As unthreatening as dinner mush. Just forks for Lou. No need for knives.

When the egg hits my forehead, it’s the happiest blow I’ve ever been dealt.

I open my eyes. Davey looks horrified. His arms fly upward in surrender. “I was aiming for your chest!”

I dig my hand into the wet earth and extract a clump of mud.

“You missed, man.”

The air between us explodes with mud as we tumble headfirst into war. It is in the midst of battle that I find a flicker of my old self peeking out.

I wipe the slime from my brow with a newfound respect for Davey Brum. It takes a certain kind of courage to throw an egg at a boy whose arm’s been chopped off.

It will take me many years to fully understand that it had to be Davey. That there are some missions so delicate, only a brother can complete them. That sometimes it takes a bond that has nothing to do with the moment and everything to do with a shared history bigger than two boys in a thicket dripping in muddy egg whites.

In the months that follow I will begin to understand that my Judaism does not lie in the stitching of skull caps. Not in the brown benches of the synagogue or even the headlines where one month later a Jewish boy from Brooklyn will become the National League’s MVP. It is not an external entity at all, but a living thing all its own. All this time, there was a rope tethering me to a greater whole, and I never acknowledged it. I will spend a lifetime exploring that bond. But right now, the only thing I know for certain is that somehow, inexplicably, I’m not alone.

“Uncle!” Davey cries as I get him in the back of the head.

I hold up my arm. “All right, I’m done.”

Davey comes closer. “You’re not a bad shot, Lou.”

I shake my head, the momentary bliss of forgetting fades away, the burn in my throat begins again.

Davey bends down and hands me a small rock. Then he takes out a pocket knife and shaves off a bit of bark from the maple fifteen feet behind me.

I throw the stone up, catch it, throw it up again.

Davey stands by the tree, watching.

“This is dumb,” I mutter.

“Just try,” he says.

I throw the rock. It hits the mark.

Davey’s smile nearly breaks his face. “Koufax!”

***

“Set the forks, Lou.”

I’d snuck in the back, leaving the new tray of eggs on the kitchen counter and ran to the shower before anyone could question me. Sniffing the air, I realize Ma’s made another pound cake.

She opens the cutlery drawer and I stare into it, my hand above the forks. I suddenly have a better idea.

Dad walks in. Ma announces dinner. In the background, Hannah whines about something. We all sit down.

It’s my mother who notices first.

“Two hundred fifty thousand people showed up. Imagine that. Newspapers are saying Dr. King spoke well—” She stops midsentence, staring at the knife next to her plate.

No forks. No spoons. Just knives.

Nothing moves. Not even my father’s eyes. My mother presses her hands flat on the table.

“Well.” She breathes out. Just like that. As if that’s all there is to say.

I lean over the table, grab the bowl of green beans and scoop a few onto my plate. Then I take my knife, lance a bean, pop it into my mouth. Chew.

For the first time all summer, my father laughs.

(Originally featured in Calligraphy, Succos 5779)

Oops! We could not locate your form.