Meters and Matches

“‘What are you doing in Tel Aviv with no money?’ I asked him. I have strong intuition, so I knew this fellow needed a little hadrachah, not just a ride

The assignment: Find the route, site, or scene that best captures your personal relationship with Jerusalem

The driver: Shimon Kohl of Hapisgah Taxis

Shimon’s Motto: Nothing makes me happier than helping people get their prayers answered

S

And so, when I ask Shimon to pinpoint the site he loves best in Jerusalem, the answer is easy: the kever of the Zvhiller Rebbe, sandwiched between the Knesset and the Supreme Court, where so many singles storm the Heavens to find their zivug. And then, he says, it’s on to the nearby Knesset Rose Garden, a shidduch hot spot where many of those praying hope to find themselves soon.

Shimon drives off to a small – and until several years ago little-known – cemetery called Sheikh Bader, the name of a former Arab village that stretched from the hilltop of Givat Ram to Binyanei Ha’umah. After the 1948 War of Independence ended in a fragile truce, the Jordanian legion made itself at home in Jerusalem, taking over large chunks of the city, including the Old City and the ancient Jewish cemetery on Har HaZeisim. Jordanian snipers would regularly shoot at the burial convoys trying to get to the cemetery, so for the next three years, until Har Hamenuchos was opened in 1951, the dead of Jerusalem were buried either in the Sanhedria cemetery or in several graveyards hastily erected in various corners of the city. One of those graveyards was a small plot behind the old Shaare Zedek hospital on Rechov Yaffo; another was in Sheikh Bader, abutting the hill where the Knesset now sits, containing about 200 graves – graves that might have been forever forgotten if not for a dream and a tzaddik’s promise.

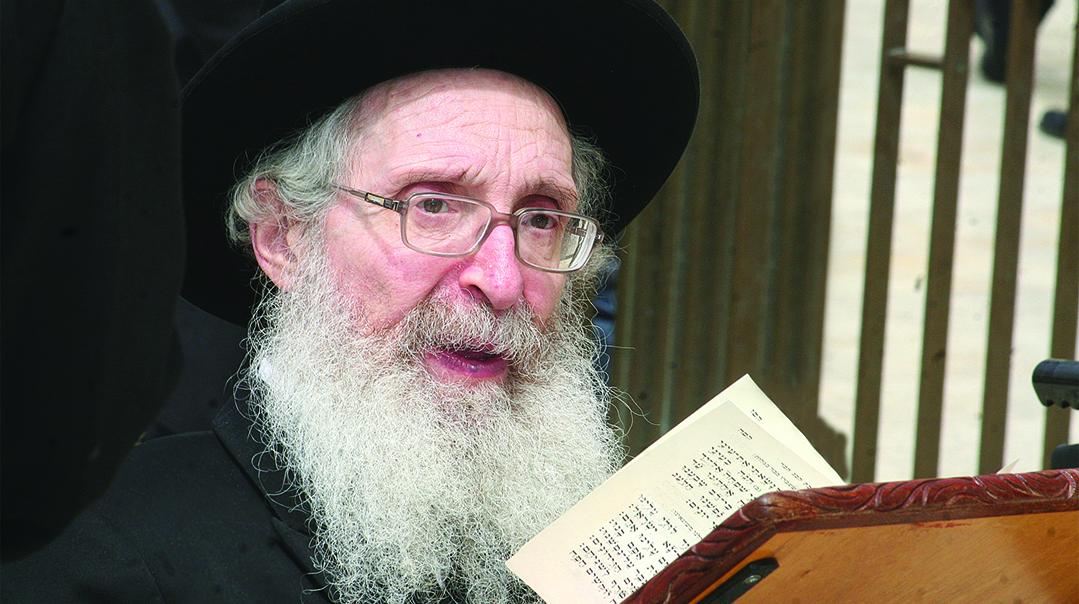

Because one of those kevarim is the eternal resting place of Rebbe Gedaliah Moshe Goldman of Zvhill, who passed away in 1950. A Torah genius and the son of the famed Rebbe Shloimke of Zvhill, he was appointed rav of the Russian town of Zhvill when he was only eighteen, after his father immigrated to Eretz Yisrael. He was soon exiled to Siberia though, but that’s when his greatness became even more apparent; during more than a decade of hard labor in that frozen wasteland, he never missed putting on tefillin, and never desecrated Shabbos. He was finally freed in 1937, joining his father in Eretz Yisrael and succeeding him as Zvhiller Rebbe in 1945. Rebbe Gedaliah Moshe, like his father, was a paragon of humility and a hidden miracle worker – his greatness known to the tzaddikim of Jerusalem who mourned his untimely death just five years later.

“There are several different versions of what happened next,” says Shimon as our taxi nears the cemetery, “but the most popular account is that about 12 years ago, a member of the Zvhiller Rebbe’s family, who lives in London and was having difficulty with her children’s shidduchim, had a dream. In that dream, Rebbe Gedaliah Moshe came to her and told her that he would intercede in Shamayim for those who would come to pray, light a candle and give tzedakah at his gravesite on Monday, Thursday, and the following Monday. The only problem was that most people didn’t even know where his grave was, and when they found it, the whole area was covered with weeds. Not only that, there’s a bird observatory nearby -- it’s an official tourist site -- and the place was full of dead birds. But the woman came, followed the instructions from the dream, and had a big yeshuah.”

Word got out quickly. In just a few short years, this dusty, hidden cemetery has become a central place of tefillah.

“Mondays and Thursdays, I sometimes make a dozen trips here,” Shimon says as he nods toward the crowds of people surrounding the gravesite. “A lot of people don’t even know what it’s called or exactly who’s buried here, but some friend or relative told them it’s a good thing to do. They just tell me, ‘take me to that place by the Knesset where the tzaddik is buried.’ We drivers all know what they’re talking about.

“Men come here, and there is a mechitzah down the middle of the matzeivah, but mostly I bring women – a lot of them come on behalf of a son or daughter who needs a yeshuah. And now there’s a new thing. People hold their phones and face-time with someone in chutz laaretz who needs salvation. Look, I don’t know all the rules, but if it works, why not?”

Today, Shimon relates, the site has become a veritable aliyah l’regel for every trouble or ailment. “It just shows you how emunah is stronger than anything else. When a person feels he has a place where his tefillot are answered, that’s where he’s drawn to. Look how many people were helped,” he says, pointing to the hundreds of scribbled notes Scotch-taped to every fence and surface, placed by those whose problem was solved and who pledged to publicize it.

For Shimon, the customers he drops off here aren’t just anonymous fares; each one has a story and he’s happy to help. “I took a young woman here recently – she told me she wants to pray for a husband, but she was dressed for the beach. I told her, ‘Listen, you’re coming to a holy site, a cemetery where tzaddikim are buried. You’re coming to a holy rav. It’s not b’seder to come dressed like this.’ She really had no idea. ‘B’emet, for real?’ ‘Yes,’ I told her. ‘This is a holy site. A little tzniyut. Either I’ll drive you to a store to go buy a shirt, or forget about this visit. Because you won’t come out b’shalom if this is how you’re going in. Not because someone will hurt you, but because your nefesh won’t be happy.’ ”

Shimon speaks to his customers like he’s a baba – when in fact, he admits a little guiltily, that although his parents were shomrei mitzvos from Kurdistan, “I’m not really so dati. But I’ve been working in the chareidi sector since I started driving a cab straight out of the army, and I can tell you every nuance – what every hat tilt means, who wears peyot long and who wears them under their kippah, what kind of hair coverings go together with Yiddish. I’ve also learned when to give advice and when to keep my mouth shut.

“Hey!” he then exclaims as I wash my hands after walking out of the cemetery, “don’t wipe your hands on your clothes – it’s assur!”

Shimon’s been transporting people to holy sites for four decades. Isn’t it a bit strange that this “new” site, just a few years old, has exerted such a magnetic pull over an entire population?

“No, it’s not strange, and it’s really very good,” Shimon says emphatically. “First of all, it’s very holy and second, it’s very close. Think about Rabi Shimon Bar Yochai – he’s a three-hour drive away. Here, you can walk from the bus station. What could be better?”

Our next stop is the Knesset Rose Garden (Gan Havradim), and Shimon is excited. He likes to think of this place as an extension of the Zvhiller kever and as a one-stop shop – from the prayer to the date.

“A bochur gets into my cab, nice hat, clean shirt, freshly showered – I know this is where he’s headed.” Instead of the young man picking up his date from her home – which is usually in an apartment building with lots of curious onlookers – most of the local chareidim arrange to meet their date in a public area. Not only do they avoid the neighbors, Shimon explains, but they also avoid problems of yichud. “And here they’re doing it with a big hiddur – this place is packed! See those two boys waiting for their dates? It’s a miracle they each meet the right girl.

“I drive young people here every day for their dates,” he continues. “And I can always tell if it’s a first date, or if they’re getting comfortable. Usually they’ll start out here, and then walk to one of the hotels, maybe the Ramada, which has a good hechsher and a nice atmosphere. But the best thing about the Rose Garden is that it’s also free, so you can get away cheap.

“I once had a bochur flag me down at the Hilton in Tel Aviv. He saw the sign on my cab that I work for Hapisgah, a taxi company in Bayit Vegan in Jerusalem, so he knew I’m based in a frum Jerusalem neighborhood. First he asked me to take him to the central bus station in Tel Aviv, and then he got up the nerve to ask if I could drive him all the way back to Jerusalem. There was just one catch — he was stuck with no money.

“‘What are you doing in Tel Aviv with no money?’ I asked him. I have strong intuition, so I knew this fellow needed a little hadrachah, not just a ride. He told me he had met this girl on a shidduch date, but he realized it was totally off the mark when she insisted they go the Hilton, where you empty your wallet for a glass of Coke. The Hilton wasn’t in his budget, but he was embarrassed and didn’t tell her, so his transportation money for his way home got used up in the Hilton lobby.

“That was the end of the shidduch, but I gave him a little advice: ‘Listen,’ I told him, ‘even if this is your first shidduch, you have to be straight. Tell it to her like it is, tell her you’re not that type of guy, you have a limited budget, and then she’ll see if it’s for her.’ Also, I told him, ‘next time, go to Gan Havradim, it’s free.’”

Shimon says he’s happy if he can help move a shidduch along, and doesn’t begrudge the money he makes or loses. “One night I pick up a boy — I recognize him by his address because his father is a well-known rosh yeshivah and I used to drive him a lot. So I drop the bochur off at the hotel, and then he realizes he was so flustered and nervous that he forgot his wallet and has no money on him. So I tell him, don’t worry about it, I know your father, we’ll work it out later. Three hours later he calls me to pick him up from the hotel. I come, they get into the cab and we drive her home, and then I ask him, ‘You sat with her for three hours with no money, which means you didn’t even buy her a drink!?’ He said, ‘You know, we were having such a good conversation that the time just flew and we didn’t even realize it!’ I guess she didn’t mind, because they got married.”

Shimon believes taxi drivers are innately good psychologists — that it comes with the territory, like sheitelmachers and personal trainers. You hear things, he says, and you develop a well-honed intuition. “If you’d sit in this seat for forty years, you’d have it too.”

Shimon remembers years back, in the days before cell phones or telecards, when everyone made sure to have at least a few asimonim — telephone tokens — on them (he had two tucked away inside his shoe), how a special tzaddik got into his cab on a rainy night around 2 a.m.

“He tells me he needs to get to his daughter’s house, so I ask him where she lives. ‘I don’t know,’ he says, ‘somewhere in Ramot. I lost the address.’ Now, intuitive I may be, but a prophet I’m not, especially at 2 a.m. in the rain. He tells me he came from Netivot to help a couple with a shalom bayit issue and it went very late. I see he’s a very special man, a tzaddik, but what can I do?

“So I find a pay phone in Ramot, get out of my car in the rain, and ask him what his daughter’s last name is. ‘Cohen,’ he tells me – which happens to be the most common name in the phone book. ‘Reuven Cohen.’ So I call the 144 information line (back then when you called 144 you’d get your asimon back) and they tell me there are 14 Reuven Cohens in Ramot. I can’t start calling people at that hour, and anyway I only have two asimonim. The operator starts giving me numbers, and for some reason, on the third number I stop her. ‘Okay,’ I say, ‘I’ll try that one.’ Sure enough, it was my passenger’s daughter.

“And you know,” Shimon adds, “I’ve become a bit of a shalom bayit macher myself.” He discovered his calling as a young driver back in the ’80s, when a woman flagged him down on a Givat Mordechai street in the middle of the night. “Take me to Dimona,” she said.

“Now, Dimona is way down south,” Shimon reconstructs the scene, “and why would she want to run down there in the middle of the night? Something was wrong. ‘Nu, what happened?’ I asked her. ‘My husband said some terrible things to me,’ she said. ‘Oh,’ I told her, ‘that’s no good. But meanwhile you need to calm down. I don’t have enough gas in the tank to make it to Dimona, so first we’re going to stop at the gas station. While I fill up, you go get a coffee and relax.’

“I became like her chief psychologist. ‘Look,’ I told her, ‘the easiest thing is to destroy. The hardest thing is to build. This is your husband, with all his faults. It’s true he didn’t talk nicely, but as long as you’re not in danger then really you should go back, and in the morning go through your options logically, rationally. If he’s not for you, leave, but do it calmly, not in the middle of an argument.’

“She was quiet for a while, then told me to forget about Dimona and take her home. Honestly, I have no idea if they stayed together, but I realized that I have a knack for these things. Over the years people spill their souls to me.”

Shimon sees all kinds of family dynamics from his driver’s seat. Like the good psychologist he claims to be, he usually doesn’t offer an opinion unless it’s requested – but sometimes he feels obligated to intervene. Like on a drive to Teverya this summer.

“The father calls me, the family is going on vacation, but because of corona and the travel restrictions, he’s taking some kids in my car, which is a seven-seater with two wide back seats, and his wife is taking the rest of them in another cab. He gets into the cab with the kids, who are so quiet it’s weird, and the whole time he’s yelling into the phone in French, arguing non-stop.

“After an hour of this, I pull over to the side of the road. ‘Listen,’ I tell him, ‘who am I, just a simple cab driver, and I don’t know French, but something’s up. What’s going on?’ So he tells me his wife sent him an email that morning that she wants a divorce. So the whole time he’s yelling and the kids are petrified.

“I tell him, ‘Look, whatever’s going on between you and your wife, deal with it, but not in front of your kids. Just shift your focus now and give your kids a good vacation. This whole time you wouldn’t let them turn on the music because you’re arguing with your lawyer. What kind of vacation is that? Let’s turn on the music and give the kids a good time.’ So the rest of the way, we put on upbeat chassidic music that the kids liked and they came to life. Five days later, he called me to pick them up. As soon as they came into the car, I saw the light in those kids’ eyes. They had their vacation and were in great spirits.”

And what happened with the parents? “I have no idea,” he shrugs. “Ad kan. Advice I can offer, but prying – that I don’t do.”

As much as he tries to focus on the good in his passengers, Shimon has occasionally been burnt.

“I want to tell you, I’ve lost a lot more than you can imagine,” he admits. He tells the story of a man he calls David, who stopped Shimon at the kever of the Zvhiller Rebbe one Monday morning, and asked if he could hire him for the rest of the day. David was a fundraiser, he explained to Shimon, and needed to hit several cities, including Beit Shemesh and Bnei Brak.

“This David fellow looked like a fine chareidi avreich, and besides, he’d been davening for success at the Rebbe’s grave, so what could be bad? I told him I take a certain amount per hour, and he said, great, let’s go.

“Now, it was a really hot day and I had a cooler with some fruit, which I took out and offered to him too. The first red light was when he took the fruit without making a brachah. But I tried to judge him favorably — maybe he said it under his breath and I didn’t notice? Maybe he’d eaten some fruit before and this was just a continuation? But there was another thing — it was a shemittah year, and he didn’t ask me anything about where the produce came from, and I don’t exactly look chareidi. Hmm… it didn’t sit well with me, but I just kept driving.

“When we got to Beit Shemesh, I told him, ‘Listen, you need to pay me something’ — I was starting to get suspicious — but he was a smooth talker and kept deflecting me. And how bad could it be, if he had the holy Rebbe’s blessings in hand? Besides, we were having some deep discussions on the way. In the end, we went to Beit Shemesh, Bnei Brak, all over, I drove him around the entire day, even though the warning bells were ringing — and in the end, he got out of the cab for his last stop and never came back.”

It’s a pretty shocking story, but Shimon takes it in stride. Like so many of the people he drives – “they open up to me because a cab driver is both personal and anonymous, you’re both trapped in this confined space, yet you’ll never see each other again” – David was, in his own way, another broken soul. And with Shimon’s own parnassah having taken a nosedive during these months of COVID, he’s become sympathetic to another person’s financial breaking point, knowing all too well what it means to despair of making it through the month through normal human effort.

“I spend my days driving people around for tefillot and brachot,” he says. “So I don’t know by now that parnassah only comes from Hashem’s open Hand?”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 830)

Oops! We could not locate your form.