Pathways of Peace

Love of the land has been infused in Shuki’s blood since birth; he’s the right man for our challenge

The assignment: Find the route, site, or scene that best captures the beauty and charm of Jerusalem.

The driver: Shuki Atias of Ramot Alon Taxis

The theme: Nothing like peace to showcase a city’s true charm

S

huki Atias reminds me of my childhood. Not because I’ve ever met the man before, but because he makes me feel like I’m about to experience Jerusalem for the first time, like back when I was eleven and spent my first summer jeeping through Midbar Yehudah, visiting unknown cousins, and buying potato kugel from Hadar Geula.

We slide into his cab and make room for Elchanan, the photographer.

“Welcome, welcome,” Shuki says, grizzled head nodding regally.

And we're off.

I’d challenged Shuki to take us on the route he’d take a tourist visiting Jerusalem for the first time. With an intimate knowledge of the city’s every nook and cranny – he’s a born and bred Yerushalmi and a cab driver for Ramot Alon Taxis for the past 20 years -- what part of the Holy City would he share with a newcomer?

Now, I’ve lived in Yerushalayim eight years, and my husband fifteen, and we love it in the way you can only love the world’s holiest, most beautiful city. But we wanted Shuki to make us fall in love with it all over again, to remind us of why we came here, of all places, to build a home.

Shuki is just a “regular” cab driver, but this challenge is right up his alley.

“I was born in Bikur Cholim hospital in 1962, the eldest of ten siblings,” he shares. He jerks his head to the right, indicating the hospital only a few blocks away. “There I grew up in the Morashah neighborhood, right near Meah Shearim. It’s where we Moroccan Jews lived, we called it Musrara back then. Moroccan Jews were put there, right on the old border between Jordan and Israel, before the Six Day War.”

Today, it’s considered a trendy haven for artists and musicians.

“After the Six Day War,” says Shuki, “our neighborhood wasn’t on the seamline anymore. It became part of a unified Jerusalem.”

Unity should be the key quality of the City of Peace, but too many elections, late night dumpster burning, and protests that block traffic for hours have taught me that it’s still elusive.

“Does it bother you,” I ask, leaning forward, “that the city of peace is anything but?”

“Mah pitom!” he exclaims. “It is an Ir shel Shalom, a City of Peace, no question! Any machlokes that isn’t lSheim Shamayim will never last.”

Well, then. I sit back in my seat.

Shuki relaxes into his seat – and story – and tells us how his father came from Morocco around seventy years ago. “He came at fifteen and met my mother here, and they built a family. They also built the land. He was a part of the Solel Boneh construction company, the first builders of the land.” Love of the land has been infused in Shuki’s blood since birth; he’s the right man for our challenge.

“So the first place I think you must see is Har Hatzofim,” Shuki says. Har Hatzofim, Mount Scopus, is right in my backyard, just a short bus ride away, yet apart from one stressful trip to Hadassah Har HaTzofim’s emergency room with my baby on a hectic Hoshana Raba, I’ve never really been in the neighborhood. But I know that “scopus” comes from the word scope, to watch, and I figure I’m in for some pretty awesome views.

Shuki drives, we talk.

“Tell us about yourself,” we urge.

He points to a long red scar on his arm. “You want to know the story?”

Of course we do.

“I have five sons, baruch Hashem. And the second son got married before the oldest. A year later, my first son finally got married and before you knew it he had two children, baruch Hashem. But his younger brother, who had gotten married first, waited one year and then two, and no children were coming. Things got tense between the two brothers, their wives started fighting. It was too hard, dealing with treatments and disappointments.

“Then I had to go in for surgery here on my arm, and when I woke up, it was these two sons who were sitting on either side of my bed. And so the first thing I said post-surgery was, ‘Kiss your brother. Hug your brother. Right here, right now.’

“My boys, they tried to protest, but I just kept repeating it. So they did. Two weeks later, I told my wife we need to invite both couples over and have a seudah. We did. Ten months later, my second son and his wife had a baby boy.”

Shuki whips out his phone and gleefully shows us a picture of fat, smiling Yonatan. “You know why he’s named Yonatan? Because Hashem natan, Hashem gave.” He kisses the screen of his phone.

“Do you understand what happened? It’s because shalom is the kli shel brachah, the receptacle that holds all blessing.” He meets our eyes in the rearview mirror. “Do you understand? Shalom, peace. It’s what Hashem wants.”

We nod earnestly as the taxi starts chugging up a hill.

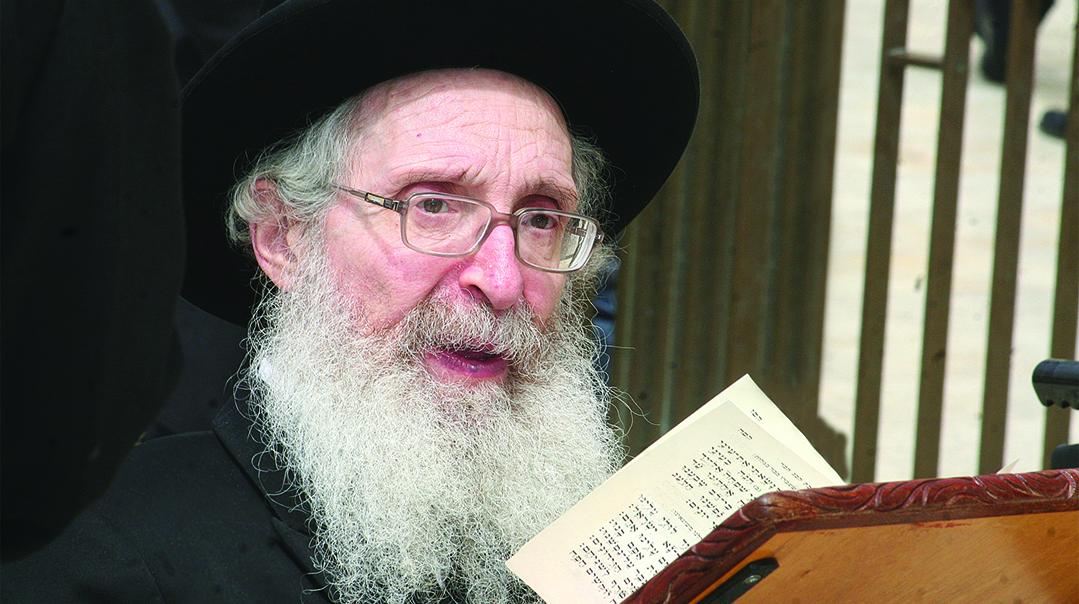

“Elul,” he continues, “is all about shalom. Rav Biederman says” — ahh, Yerushalayim, where your cab driver quotes Rav Meilich Biederman — “that Elul is all about vatranus, about letting things go. You be mevater, you let things go for the sake of shalom, and Hashem will shower you with brachah. We learn this from Rav Puppa visiting Rav Huna when the latter was ill. Rav Puppa told the talmidim around the bedside to prepare burial shrouds, that Rav Huna was going to die. But a week later, he goes to the beis medrash and finds Rav Huna sitting and learning. Embarrassed that he had been so wrong, he asked Rav Huna what happened. And Rav Huna said Rav Puppa hadn’t been wrong, he really had been dying, but at the beis din shel maaleh they saw that Rav Huna was always mevater in this world and so they were mevater on him. Being mevater gives you a direct connection to Hashem. Like a fax! You understand? We’re here. Out.”

Our Elul shmuz apparently has ended and we hop out. Elchanan starts snapping, and I’m speechless, because the entire Jerusalem is laid out in front of me like an exquisite patchwork quilt, and momentarily, it makes sense that such a tiny city in such a tiny country can have such a large impact on the world; its beauty shimmers with power, both tangible and elusive.

Shuki comes to stand next to us, and a slight breeze ripples through one of the most oppressive heatwaves in the past hundred years. “See below? That, over there, is Isawiya, an Arab village.”

“Are they friendly to Jews?”

Shuki looks at us and adjusts his small knitted kippah. “Do I know? All I know is ein emunah bagoyim.”

Right.

“And there is the clinic for soldiers, any soldier who doesn’t feel well, he goes there.”

We admire the view awhile longer, take some photos, and then we’re back in Shuki’s clean, air-conditioned cab.

“Now we will continue to Har Hazeisim. It’s in an Arab area, yes, but there’s police there, don’t worry.”

I promptly begin to worry but the ride must go on.

“This is Augusta Victoria Hospital, in the neighborhood of A-Tur. I don’t like to come here, because the locals don’t drive well.” Coming from an Israeli cab driver, that is a frightening assessment.

“They don’t drive very peacefully, the Muslims. And it’s strange,” Shuki points out, “because Islam means salem, peace.”

We all snort a little at this and then Shuki tells us that he speaks several dialects of Arabic. He starts spewing phrases with very impressive fluency — it’s Egyptian Arabic, he says.

We spy a large house right at the entrance to the graveyard — just seconds from the wild Arab traffic — proudly flying the Israeli flag.

“Yes, it is a Jewish family,” Shuki tells us.

We stare, openmouthed, as several kippah-toting little boys run up the stairs to the house, followed by a little girl in braids and sandals.

I cannot fathom why anyone would want to live here, amid the chaos and fear. Then we disembark and I look out at the view and I get it. Almost.

Har Habayis is so close, you can see the detail on the Omar Mosque sitting on our holiest spot in This World.

I forget that I’m scared of being in this unpredictable Arab village and just drink in the view.

Shuki begins pointing things out. “There’s the Omar Mosque, the Al-Aqsah Mosque, and under the Omar Mosque is the Even Hashtiyah, the cornerstone of all creation. All the brachah in the world comes from there. You see those stairs, those are the stairs of Dovid’s Shir Hamaalos from when he began building the Beit HaMikdash. And you see the Shaar Rachamim? Now it is solid stone, sealed shut. But when Mashiach comes, it will open and he will enter from there.”

Amen, b’karov.

Shuki sounds completely confident in everything he is sharing; it takes no effort, no planning.

I’ve met many cab drivers in the eight years I’ve lived here (nine if you count seminary, although most people don’t) and they often fall neatly into categories. It’s not split up by their looks. Those range from swarthy and grizzled to young, gelled, and cologned. It’s not ethnicity, either. French, Moroccan, Tel Avivian, Yerushalmi; they come from all over the globe. The categories are only these: the ones who are die-hard Jerusalem-lovers and the ones who excitedly ask about America and its shopping and Trump. Shuki belongs to the former, so unabashedly in love with his birth city.

“I love your love for Yerushalayim,” I say, somewhat hesitantly.

He looks out at the view. “Betach, of course,” he says. “Ein k’Yerushalayim. There’s nothing like Jerusalem.”

We pile back in and drive down the steepest, narrowest road ever created, practically brushing the walls on either side.

“This road is Gat Shmanim, the oil press, where they would press Har Hazeisim’s olives.” I hope it doesn’t press modern-day taxis.

We turn left toward the Kotel, so Shuki can show us the Shaar Ha’Ashpos. We get out at the gate and turn around to look up at Har Hazeisim, and see how far we’ve traveled down in just minutes.

Back in the car, we slowly circle the perimeter of the Old City. “That’s Yemin Moshe.” Shuki points out the window to the popular spot, known best in my circles as most popular site ever for professional photo sessions. “It’s named after Moses Montefiore.”

This announcement causes Elchanan, our photographer, to break into happy song; Shuki heartily joins along.

We just nod politely along, feeling very American as they sing an Israeli folk song extolling Sir Moses Montefiore’s kindness, ending with a rousing “hurrah” of sorts:

Vehu ala lamerkavah ve”diyo” lasussim amar

Ufo matan beseter, ushamah nedavah

Po tz’vita balechi o lituf shel ahavah

Ulechol haYehudim simchah uga’avah

V’chol hakavod lasar, v’chol hakavod lasar!

Once the last note dies down, I ask Shuki if he likes his job.

“I do. I get to meet nice people, it’s good work.”

We drive into the Old City, and admire Migdal David.

“Am Yisrael comes every night of Elul to the Kotel to recite Selichos, this way, through Shaar Yafo,” Shuki tells us. “You know, when I was single, I would walk every Shabbos to the Kotel from Musrara, to daven vatikin. And Friday night, we did shitat Reb Yehudah (early Shabbos).”

Then Shuki and Elchanan tell the story of two tombs set off the side of the road, just as you drive into the Old City, sticking out from behind a bank and an ATM. “These are the two architects who designed these walls five hundred years ago, during the Ottoman Empire. They made a mistake in the design, so the sultan said he’s going to cut off their heads, but give them nice graves in this prime location.”

Lovely.

We drive through the Armenian quarter, then the Jewish quarter, admiring the quaint stores and archaic arches.

“Here’s the beit knesset of Rav Yehuda Hachassid,” Shuki says. We continue down. “And there’s Har Hamoriyah. There Avraham brought Yitzchak as a korban,” Shuki says briskly.

And I know without asking that his emunas chachamim is probably as strong as his love for his country.

“Have you ever driven anyone famous in this cab?” I ask.

“Lots of times! I’ve driven Rav Bentzion Muzafi, rav in Sanhedria. And the mekubal Rav Tzion Brachah, who went to Gilo every day to daven in the direction of the Arabs that they shouldn’t give us tzarot.”

I guess you never know whose zechus it is when there’s peace in the city.

“I have a question,” Elchanan says, as we leave the Old City behind.

“Yes?”

“From all your years driving, is there a passenger you’ll never forget?”

Shuki thinks a moment, as we head toward home.

Then “Yes! Yes yes yes!” and he launches into the following:

“I was driving through Kikar Shabbos and I spotted an American couple standing on the corner looking terribly upset. They weren’t flagging a cab, but I just had to stop and ask them if everything was all right. They tried to send me away but I insisted that I wanted to help them. Finally the husband told me that they had just taken an Arab cab from the Kotel and he had left his cellphone in the charger. When the cab dropped them off at Kikar Shabbos, the driver sped away with the phone, not even waiting to be paid. All this man’s work – his contacts, his emails, his appointments — was on his phone, and he just couldn’t calm down. He was so frustrated that he getting very upset with his wife, as well.”

So Shuki told them to come into his cab and he drove them back to the Kotel, where he stopped by the little Arabic souvenir stands and asked if anyone knew this driver. He didn’t make much headway, but Shuki gave his phone to the distraught man and told him to keep trying to call his own cellphone. No answer. They tried for an hour, then Shuki took a turn calling and he left the cab driver a message in fluent, no-nonsense Arabic. “I told him you can answer right now when I call, or I’m going to the Kishleh, the police station and former prison right here in the Old City, and having them call you.”

No answer, so off he went, American couple in tow, to the police. When they called, the driver showed up immediately, phone in hand. The couple was all smiles, and that’s how Shuki saved the day.

No one asked him to help – certainly no one asked him to lose at least an hour of income — but he was in the right place at the right time to change one American’s memory of his trip to Israel from “that terrible time that someone stole my phone” to “the trip when that Jerusalem cab driver restored my faith in humanity.”

We all agree it’s a great story and then we pull up outside our building.

“Thank you,” we tell Shuki. “You gave us such an incredible trip.”

And it was — though there wasn’t much fanfare, just genuine appreciation all around for good people, hidden history, and the beautiful city of Yerushalayim.

Shuki smiles and waves, then speeds off in his clean, air-conditioned cab, perhaps to spread peace somewhere else.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 830)

Oops! We could not locate your form.