Meal Requests

There hadn’t been much time to decide and even though Phyllis Lang wasn’t a spontaneous sort of person, the prospect of being quarantined in her apartment made this seem exciting

It was an assistant manager named Shaya Mauer who made the decision, though he’d never been charged with decision-making before. The real manager was at a convention and Mr. Feder’s son-in-law wasn’t answering calls and the Board of Health kept updating their protocols and eventually, Shaya stepped up.

He was sweating profusely, actual sweat which he felt trickling down his back, and he kept repeating that he didn’t see another way and he hoped Mr. Feder understood the pressure he was under, but that was it. As the most senior executive at The Cove in Morgan, New Jersey, it was his job to make the call.

He walked around the lobby with what he hoped was an appropriate expression on his face and informed them all, Palma the head nurse and Michelle from billing who’d been there longer than him and Jose from custodial services, that as of three p.m. the next day, the facility was closing.

Dr. Liu, the chief doctor, wrote an email suggesting that those residents who could return to their own homes should do so immediately, until the staff could come back.

All rehab sessions were canceled. They would tread water for a few days and hope it would pass quickly.

Shaya Mauer felt very leaderly as he said this, “We’ll tread water until it passes,” and over the course of the afternoon, he got sort of good at it, nodding his head, frowning, and assuring them that he would follow up by email with all relevant details about payment for March and the schedule for reopening.

The first day, he was calling it Corona-19, a fact that would embarrass him later, a blot on what had otherwise been a flawless performance. Mr. Feder himself called to commend him later, a few days after the large brass gates outside The Cove were locked and only a single back entrance remained open.

The Cove wasn’t a place that ordinary insurance plans covered, Shaya liked to tell people. Visitors were often awed by the décor and view, and the food, he liked to say, was “next level, better than any restaurant in the city.”

But on Tuesday March 17th, it was exactly like every other rehabilitation center — people speaking quietly, urgently, confidence shaken by the sense that something bigger than them was happening. Tammy and Barbara in admissions hated each other so much they’d barely spoken in months, but as they packed up to leave early on that Tuesday afternoon, Tammy smiled shakily and Barbara nodded and said, “I know.”

On Wednesday morning, the waves were like playful children, deep blue and white-rimmed and wilder than usual, but inside the low, gray building, the mood was somber. Minyanim and shiurim were cancelled along with all other activities, the hallways void of conversation, none of the thump-thump of walkers or clack-clack of wheelchairs. The PA system, usually a stream of music and announcements — they even had a “motivator” who came every week and filled the hallways with exuberant “you can do it” and “today is the day” stuff — was stilled.

Shaya Mauer, working from his home in Kensington, was overseeing the basic running of the facility.

Most clients had cleared out, returning to the relative safety of home and family. There were just a few left — the Horowitzes in 215 who preferred to remain in place, since they were too frightened to go anywhere, and Mrs. Shain, who didn’t have the strength yet to go anywhere. There was also the wealthy man from Argentina who didn’t really speak English, but he’d broken his legs while in Manhattan and so ended up at The Cove, the only fully kosher rehab center overlooking the gentle waves of the Atlantic Ocean. There were no flights home for him, so he was staying put.

Then there was Mordche Lemberger. That was tricky.

Lemberger was younger and more vibrant than most of the other clients. He’d had hip replacement surgery and really, he could have gone home — he just didn’t want to.

His wife had passed away a year and a half ago, and he still had that vacant, distracted look of someone who hadn’t really adapted to reality. He had children and children in law — his room a bustle of action and noise, loud daughters who moved furniture around and grandchildren who came to spend Shabbos — but of course, Dr. Liu had made it clear that moving in with the children wasn’t an option. COVID was a wall and he was trapped on the other side.

Lemberger was a friendly guy, and he and Shaya often joked around after Minchah. They had a nice relationship, but this phone call wasn’t that nice.

Shaya, following orders from above, was trying to persuade Lemberger to clear out, to go to his big house off 16th Avenue in Boro Park. There was no therapy happening anyhow.

“Reb Mordche, we’re developing a plan for remote therapy sessions, of course it won’t be the same, but it will be something, and you’ll be in your own daled amos, which itself is wise. Nothing safer than home, right?”

As if he hadn’t spoken, Lemberger repeated, “I’ll stay here, I don’t need much. It’s fine.”

Frustrated, Shaya decided to call the children. Maybe they could help him out.

For some reason, Blimie was taking it the most personally. She left a long dramatic voice note on the family chat, a blow-by-blow account of her conversation with Mr. Mauer from the rehab place.

Tatty is being stubborn, she said. He doesn’t want to leave, beshum oifen. Of course, it’s hard for him to be home without Mommy, nebach, and he can’t come to us. So takeh what should he do? Should we be trying to convince him to go home anyhow? They don’t want people there, they have no staff and don’t want to take chances with anything, they’re worried. Mr. Mauer promised me they’ll take Tatty back once this passes, guaranteed.

Chaya Gitty, who was a daughter-in-law, had bigger worries than Tatty, to be honest. She had never made Pesach before, and this year, Tatty had been planning on taking everyone to Florida. She’d been in charge of the logistics, finding the houses in Orlando, working out the meals with the caterer, and Yanky had figured out the flights. Didn’t seem like that was happening. What were they supposed to do?

Later that night, on another chat that Blimie had with just the sisters, she sighed and reminded the others that she’d been saying all along that he pashut needed to get married, he needed a wife and there were no two ways about it. Suri thought he needed more time, but now look, he was alone with literally no place to go. Literally. Florida was off the table. He couldn’t be around the eineklach. Poor man, he had to fight just to stay where he was, since he had no koyach to go back to his lonely house. Blimie said that Mrs. Kempinsky had a list of names of eligible women. Tatty was only seventy-two, personable and handsome.

He was a catch, Suri agreed, and everyone felt a bit better.

The notice came the week before Pesach, one typed letter for the last few people at The Cove.

To our Valued Clients,

In these unprecedented times, we are doing our best to maintain the standards of The Cove, and baruch Hashem, we are ready for Pesach. It’s different than in years past, and it’s our hope that you enjoy the Yom Tov in a healthy, safe way.

There will be no minyanim or communal gatherings. Family members will not be allowed in and residents are asked not to leave the facility for the duration of the Yom Tov.

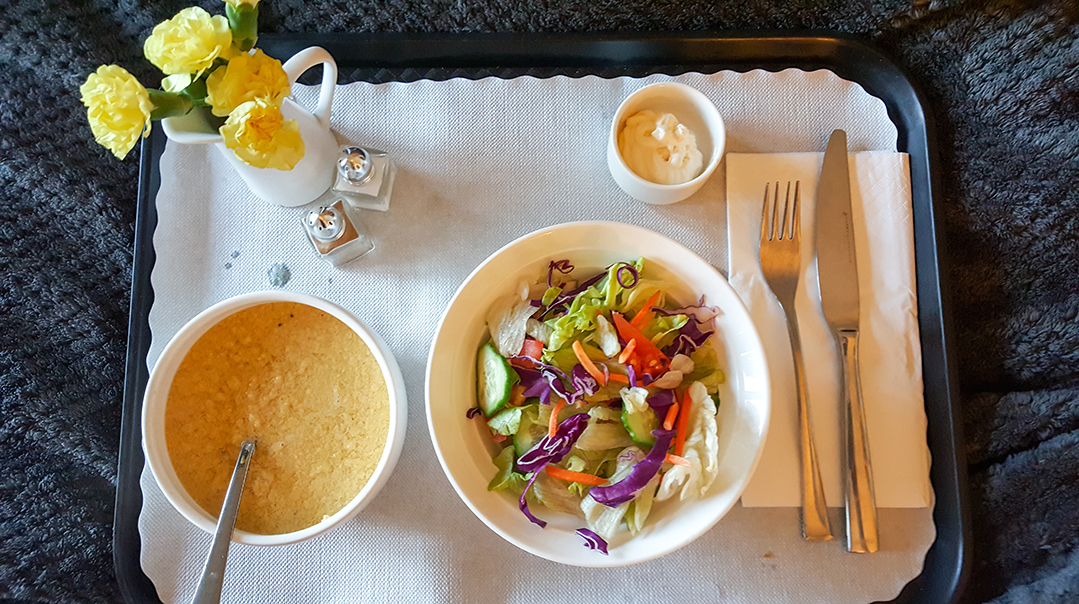

We are grateful to the staff members who’ve stayed behind to see to your Yom Tov needs. Please respect their safety and allow them to keep their distance. Nurse Jasmine Demoulya will be in her apartment on the lower level and will check in with each of you daily via phone. On Yom Tov, she will knock on your door to answer any questions. Mr. Hector Torres will be available for maintenance questions at extension 213. Our kitchen has been made ready for Pesach by a team of mashgichim, and has been completely disinfected. We would like to welcome Mrs. Phyllis Lang, who will be preparing the meals in place of Chef Lommer. They will be available for pickup in the hallway, just outside your room. See schedule for times.

Next year in Yerushalayim. Thank you for bearing with us,

Irwin Feder and the Quantum Healthcare Family

Phyllis Lang arranged the armchair so that it was facing the window and allowed herself to relax. The ocean was lovely, so there was that. And the money was more than fair. And, if she was looking to see the positive — and she was a person who always looked for the positive — she hadn’t really had any Yom Tov options.

Since the divorce, it was either with Chaya in Teaneck or, when she could swing it, with Jeff in Efrat. But not this year, not with the virus ripping through the air and attaching itself to people just like her, in their mid-sixties. So it was either home alone in Baltimore or here, working out of a state-of-the-art kitchen, sleeping in a room with a gorgeous ocean view.

During the year, she cooked for a large yeshivah high school and sometimes helped Metzuyan Catering if they had a large Shabbos job, but she’d never done a Pesach program before. This was an emergency. The regular Cove chef was no way coming to work, and it turned out that the mashgiach knew her nephew, Kalman, who’d thought to call her, Aunt Phyllis in Baltimore, maybe she was open for a Pesach gig.

There hadn’t been much time to decide and even though Phyllis Lang wasn’t a spontaneous sort of person, the prospect of being quarantined in her apartment — no meals with the Frieds or Hershkopfs, no visiting her own children — made this seem exciting.

Pesach chef at The Cove, cooking for a grand total of ten people. No gebrochts, which was new for her, and also no staff at all. The order had arrived from Kosher Pantry, all the meat, fish, and groceries unpacked by Hector, but now she was on her own.

She looked at the list. The older couple, Horowitz, didn’t eat very much, and the gentleman from Argentina would eat pretty much anything. There was a Mrs. Galinstein who was allergic to eggs, which was complicated, and a Mr. Landau who didn’t eat fish on Pesach at all.

Erev Pesach lunch would be tricky, but once Yom Tov started, she thought she’d be okay.

Mordche Lemberger hadn’t left his room in over a week. When the weather was nice, he sat out on the balcony, trying to keep his learning sedorim and do a little business.

There wasn’t much to do, that was the problem. No one was buying, no one was selling, there were no deals to review, no fine print to analyze. He wasn’t a big reader and the news depressed him. Everything depressed him. The kids, the eineklach, bright spots in his life, didn’t stop calling, but he was never sure what to say, how to react. Malka had dealt with all of that: “Did you notice Blimie looks extra anxious,” and “Why you do you think Duvid’s Rivka’le is so cheerful, she’s probably expecting, no?” and, “Mordche, give Shloimy some project at work please, poor boy.”

Now, it was all a guessing game. Yes, he was eating well. No, he didn’t feel symptoms. Wow, little Chaim Burech really knew how to say over a Mishnah, ba’al peh, no less. Psshhhh.

He missed people. Berish from shul, Neiman from the office, the Ruv’s son-in-law who he learned with after Shacharis. There was nothing, now. Just a constantly ringing phone with children he loved but couldn’t say he really knew, and footsteps in the hall a few times a day.

He did the daf, the parshah, Mishneh Berurah. He played chess on his phone. He scanned the Times. But there was nothing pulling it all together.

He’d been alone since Malka had died, but now he was also lonely.

The note was handwritten, Scotch-Taped to the top of the plastic container.

Mr. Lemberger,

I hope you are well. My name is Mrs. Phyllis Lang, and I’ll be the chef here over Yom Tov. I am eager to prepare delicious meals and seudahs and would be happy to try to accommodate any requests you may have. There aren’t very many people here and perhaps the personal touch can add a bit of simchas hachag. Thank you.

Sincerely,

PL

He read the note twice and then shrugged. It was strange. Food is food.

He considered answering her, but what would she know about greeven or borscht? Her name was Phyllis.

Later on, closer to Yom Tov, when he was already wearing his beketshe, he picked up the paper and read it again. Maybe this was his way of honoring Yom Tov, to tell her about what Jews eat on Pesach. He contemplated it, but then the phone rang again. Malka’s nephew Lipa, just to say a gut Yom Tov, which he did by sighing expansively and saying, “shvere tzeiten, shvere tzeiten,” and irritating Mordche.

Mrs. Lang,

This is Lemberger, from 127. You had asked about food before Yom Tov, I never got to answer. I apologize. At my office, we have a policy that all emails must be answered by the end of the day, but this isn’t the office, I guess.

I wanted to compliment the food, especially the lokshen. My wife told me once how hard it was to make lokshen that are so thin on Pesach. She showed me how the tips of her fingers were a little burnt. Your lokshen was thin and geshmak (enjoyable), and reminded me a bit of old times, happier times.

I wanted to thank you.

“Nu nu,” Mordche said out loud, to no one, and folded the paper. They had set up a small table in the hallway where the meals were laid out, residents tiptoeing up one by one to take their trays. He wasn’t sure who put them out, and he hoped his note would find its way to the cook.

To make sure, he added the words “Mrs. Lang” to the other side of the paper, so that it was visible. When she came with breakfast, she would see it.

On Chol Hamoed morning, after he davened and ate breakfast, he did a FaceTime with all the eineklach. They had prepared a skit and special song for him. It was sweet and for a few minutes, he forgot where he was. Some of the teenage bochurim took over the screen and sang his special Seder niggun, Adir Hu, and even though there was a lag and Blimie’s Moishy was off-key, Mordche was moved. He’d sung it alone this year — it had actually been strangely comforting, sitting on the balcony and singing out loud into the roar of the waves — and hearing them try was nice. It meant something. Maybe one day they would sing it at their Sedorim, he thought. May their wives all live long.

He hung up and sat in the large armchair, feeling sort of happy… it was Chol Hamoed. In normal times, he would be eating a late breakfast, Malka coming out of the Pesach kitchen to join him, perhaps an einekel or two sitting at the table as well. The kids would be discussing where to go, and then tease him about joining. He would laugh and say, “I’m an alte Yid, the zeide needs his nap.”

Once, he had given in and joined them on a trip to Bronx Zoo, but the kids had all been so jumpy and eager, none of them lingering or stopping to really observe the animals, so it had been moving, moving, moving all day. Mordche had come home with a headache, feeling dizzy and, for some reason, sad.

Mr. Lemberger,

Thank you! I’m old enough, I think, that I have learned to accept compliments. It wasn’t easy, but it’s easier than it used to be. It comes with experience. Your wife must be a fantastic cook.

PL

This was taped to the top of the plastic container of vegetable soup.

He wrote back just as soon as he finished eating.

Mrs. Lang,

The lunch was delicious. Thank you. My wife, Malka, passed away just over fourteen months ago. She would have appreciated what you did with the soup, not blended like baby food but not too chunky either.

He did end up taking a nap after writing it, and when he woke up, he peered out the door and into the empty hallway, curious to see if the note was still there.

It wasn’t.

Supper was brisket and mashed potatoes, which he liked, but there was no note, and Mordche’s heart sank. He had a phone chavrusa with the Ruv’s son-in-law and then the eineklach included him in a trivia game they’d made special for him. Zaidy’s father was from Toshnad, who was the Rov? When Babby lived in Crown Heights as a girl, where did her family daven?

There was no note until breakfast.

Mr. Lemberger,

I apologize I didn’t write back last night. I was working all afternoon and the time slipped away from me. I very much appreciate your kind words. I am so sorry for your loss. I can’t imagine what that must be like.

My own husband is still alive. He’s just not my husband anymore. He got tired of the whole thing, he said.

I would like to try some sort of pancakes, but my mother made them with matzah meal, which is gebrochts, so I will try it with potatoes instead. Please let me know how they are.

I hope you can enjoy your Chol Hamoed here, even though it’s not home.

PL

Later, after lunch was prepared and Phyllis Lang had a few minutes to rest, she looked out at the ocean and wondered if she came across sounding strange, like one of those women who told you their problems at the push of a button.

She had never been a crybaby, never needed others to understand what her life was like. Sam had pulled out one day, claiming that the whole thing — two kids who never stopped kvetching, as he put it, the long hours at a job that never paid enough money anyhow — was just too much. She’d been thirty-three years old and even though he’d drained every drop of her energy with his list of grievances, once he left, she felt so broken that she didn’t even have strength to cry.

So she’d gotten busy. She’d worked longer hours, then learned Chumash with Jeff at night and done homework with Chaya. She’d taken on part-time work as a math tutor to make sure Jeff had the sort of bicycle he wanted, and always had homemade ice cream in the freezer so that their friends enjoyed coming by.

She’d done well, and she knew it.

Sam had gone back to New York, where he’d remarried and divorced, flitting in and out of the children’s lives. In 2000, he’d come back to Baltimore for Chaya’s wedding, and hung around for a few days after, she wasn’t sure why.

Finally, he asked if he could speak to her and came over to the house. Standing on the front porch, he said that he’d been young and stupid and was sort of amazed at the job she’d done with the kids. And with herself to be honest.

She knew she’d done a good job. The kids were great.

Maybe they could turn the clock back, he said.

She’d smiled at him, slowly, she hoped kindly, and then stepped back and gently closed the screen door so that it echoed.

She wouldn’t give him the satisfaction of explaining that he didn’t get to do that, to waltz in now when she’d been the one to take two children to the emergency room in the middle of the night when only one needed to go; when, over twenty summers, her friends spoke gushingly about how peaceful their houses were with the kids in camp and they could finally hear their husbands talk and she would just listen, not wanting to admit that she was counting down the days until there would be noise in the house again.

Nope. Bye, Sam. Sorry.

And here she’d gone and opened up to a stranger. Less than a stranger. She’d seen him, Mr. Lemberger, walking up and down, doing his exercises in the empty hallway, dignified in his striped woolen vest, determined to walk straight, shoulders squared.

She didn’t think he’d seen her, or that he knew a single thing about her. He was lonely, was what she thought, and starved for any sort of human contact. That was it.

They were very good, your pancakes, sort of like potato latkes, and who doesn’t enjoy that? I hope by Chanukah this will be over and we’ll be able to eat together with other people again. With Hashem’s help.

That’s a terrible thing, divorce.

Here, Mordche had stopped writing for a moment. He’d always been a good communicator, not just in Yiddish and English, but in other languages too. He’d prided himself on the Spanish he’d picked up in the office, and he enjoyed asking Luis, one of his chief foremen, “Cuando se hara el trabajo?”

But here, he was writing not in his own style, but in hers, imagining how she spoke and replying in kind.

Just terrible. Because I feel like, when I lost Malka, it was painful, but I could survive by taking it one minute at a time. There were happy memories. I would look at pictures. That gave me koyach.

Mordche had once tried talking about this before, but it hadn’t worked. He’d asked Blimie if she thought about her mother a lot, and how she got through the day. “Tatty,” she’d responded too quickly, like she was waiting for the question, “Mommy would want us to be happy, not to dwell on the past.”

So he hadn’t talked about it. There had been plenty to distract him. Business was good, they’d completed the Autumn Gardens purchase and developed the medical complex near Philadelphia. There had been simchahs, so many simchahs, baruch Hashem, chasunahs and bar mitzvahs and always, speeches about Bubby, her generosity, her Tehillim, her seichel.

He’d sat with his head bowed, mourning none of those things: instead, he missed her way of sniffing when he made a joke, the way she absently tapped her coffee mug on the table when it was empty, the way she said “a mazel’dige a voch” after Havdalah, even before he finished drinking the wine.

Now, as he wrote, he let himself go there.

The kids have a way of moving on, they have fuller lives, maybe, but I can only go on by living with some part of the past in front of me. If that makes sense. Maybe it doesn’t. I’m not a psychologist. But I wonder, what does someone do when they’re alone after a divorce, when even the memories are difficult? That’s so much harder, it seems to me.

I can pull out memories to push me forward, but you probably try to forget, so how do you do it?

Regarding your Chol Hamoed wishes, I’ll be honest, there is something sort of pleasant here. I didn’t expect it. When I was young, the house was often noisy and I needed space. I would say that I’m going to learn, but really, I just wanted to sleep. I would go into my study, close the door, and nod off within a minute… These days, I say I want to sleep, but I end up learning more than I used to. Sorry for rambling.

Thank you again for the chremslach, as we call them. They added to oneg Yom Tov.

He walked down the empty hall, headed to the kitchen. Then he changed his mind and walked back, placing the note on the low wooden table where she left the suppers.

Early Tuesday morning, the last day of Chol Hamoed, Mordche went for a walk, but instead of staying in his own hallway, he walked through the empty lobby and ventured into the atrium. Everything was shuttered and dark, the parking lot in front empty and the highway, visible in the distance, completely silent.

It would have been nice to see a human being.

Breakfast was hardboiled eggs and tomato salad. There was also a note.

I appreciated your note and the point you made.

It’s not simple. There are plenty of happy memories I could have used to carry me — the children, my own parents, many beautiful times that don’t include my marriage. The summer sunsets on Coney Island, walking between my own Bubby and Zaidy, playing in the snow with my children, dancing with Chaya at her wedding… I could have pushed Sam out of my mind and moved on, but I didn’t want to. You see, Sam would show up from time to time and I wanted my children to have a father.

So I had to smile and remind them to call him before Shabbos. When he sent money here and there, paying for camp or yeshivah, I made sure they thanked him. So no, I couldn’t just forget about it. I had to let him live on, for their sakes, and I didn’t get to slam any doors.

What did work for me, though, was creating rooms in my heart. The bitterness stayed in one room, but I had other rooms to go to, happier places.

How I got through the day? Not just with happy memories, but also dreams of what would be.

Now, I look at my children and their beautiful families and I know I got what I was hoping for. This was a hard Pesach for all of us — I missed my grandchildren something fierce, but I know I have them, and I know how lucky I am.

Mordche had davened Shacharis on the balcony, then hurried out to check the table even before folding his tallis.

Now, he sat, the tallis in a little heap on the dresser, and read her note.

Mordche had never been a big crier, but this was different. He was moved, awed even, by how unspoiled this woman was, how much he’d taken for granted and never even stopped to appreciate. He wished he could read this note to his children, tell them about rooms in the heart and living not just for the past but for the future too.

He wished he could tell them about a woman who considered a beautiful sunset a happy memory, who didn’t need Florida or Switzerland or more shopping, always more shopping.

Playing in the snow with my children. It made his heart hurt, feeling bad for her and envious of her at once.

But when he nodded off after eating breakfast, it was the words “something fierce” that played in his mind, an expression so unlike anything he, or anyone he knew, would use.

He woke up after twenty minutes and didn’t wait, washing his hands, tearing off a large piece of paper from the Investors Savings Bank notepad.

I’m not the most sociable person. I’m friendly, though, I try to be pleasant. My wife liked to go places, to see people, so I made peace with it. I would stay at chasunahs longer that I wanted to, because she was having a nice time, and make small talk with people I didn’t find that interesting….

Anyhow, one night I was sitting in Ateres Chaya way too long and a person next to me at the table was telling me about having suffered losses, and he said something interesting. He told me, “Everyone says that I should learn to separate, to mourn in private, all that stuff, but I do it different. There’s nothing wrong with grieving. It helps me enjoy simchahs more. If you let yourself feel, you let yourself feel.” Then he was quiet and we both went on eating soup.

But lately, I think about what he said a lot. He had a point, that’s for sure. If you let yourself feel, you let yourself feel.

He went out to put it on the round table even though lunch wasn’t due for two hours.

It was Erev Yom Tov, but Phyllis Lang needed a bit of air. There was that nice balcony off the lobby. It was locked, but she had the combination. She took off her apron and laid it down on the large steel counter, walking down the empty corridor toward the lobby.

When she came up, she saw the note, and she found that this made her happy. She lifted it gingerly, like it was an old picture, and carried it outside with her.

Over the years, there had been opportunities to get married again.

Several, in fact. For years, she’d resisted. She wasn’t that lonely or that eager.

Levine was a nice man, but she hadn’t had the energy to try, and later, Aron Fendelsky, the architect, had called to ask her to dinner, and she’d given it a shot. It had been pleasant enough, but she couldn’t bring herself to match his level of enthusiasm, his willingness to try again, his determination to move on with his life. She couldn’t think of a reason to say no, but there was nothing that allowed her to say yes.

Norman something or other, who’d never been married and was polite and well-dressed, met her in Manhattan and they went for a walk. It was pleasant, but while he was talking about his travels, she was remembering a long-ago trip with Sam and the kids. They’d come to Manhattan for two days and not far from here, right off Fifth Avenue, there was a street magician performing on the corner.

A small crowd had gathered, parents taking pictures and children laughing. Sam had been restless, calling out “wait, the box has a false bottom,” and “you have a code in the way the assistant says the word ‘boy.’” At one point, the magician said, “You clearly know the secrets of magic, sir, so let’s keep them secret,” but Sam didn’t let up. “It went up his sleeve,” he shouted, and the magician looked at him and ended the show. Just like that.

That’s what Phyllis was thinking as courteous, attentive Norman shrugged and said, “And that was the last time I tried riding a bike in Tokyo.”

Now she sat on the low, wooden chair and breathed in the pungent, salty ocean air.

The paper fluttered in the breeze and she clutched it. This was a man who waited at weddings until his wife was ready to leave. It fit, she thought; there was something steadfast and loyal in the way he made his way up and down the hall as he did his exercises in his gray-pinstriped vest.

It was too windy to write outside, so she went in and leaned over the front desk in the long, empty lobby.

That man at the wedding, he might have been right that locking up grief doesn’t always work, and it might be easier to just let it flow, always, and enjoy the happy moments more fully, if I understood him correctly. But the problem is, what about the people around you? They don’t have to suffer, they have their own grief, of course.

Creating rooms in the heart isn’t something you do for yourself. It’s something you do for others.

She didn’t bother with the table. She went and taped it to the door of his room.

About an hour before Yom Tov, Mordche took his phone off the hook and tore of a piece of a paper from the pad.

Mrs. Lang,

You helped me understand my parents a bit more. I grew up after the war, they didn’t talk very much, and to be honest, I didn’t want to hear. When I got older I wanted answers, but they were already trained in silence. In my father’s last few months, we talked a bit, and he told me that not a night passed in which he didn’t remember his first wife and children — but only at night, only under his blanket.

When I shook off my blanket in the morning, Mordche, I shook off the sad thoughts, he told me.

That’s been the story of these days, for me, of this Yom Tov. There’s a mitzvah to be happy, so I tried to remember that, to shake off the blanket of loneliness. The Eibeshter gave me wonderful children and every one of the eineklach is a gift. He made a world that’s perfect, and just looking out at the ocean fills me with wonder. Like you wrote, rooms in the heart.

Thank you and have a gut Yom Tov. (I hope you will get this before Yom Tov, even though there are no more meals. I’m leaving it on the table and hoping….)

Mr. Lemberger.

Happy Isru Chag.

I hope the second half of Yom Tov was pleasant for you. I appreciated your note and also, the chance to say gut Yom Tov in the hallway. I’m not always a shul-goer, but I never miss Yizkor, so this was a first. It made it easier, I guess, that no one in this world really got to say Yizkor, so I had this image of my parents surrounded by all their siblings, Uncle Harry and Uncle Shimon and Sadie and Harriet and Sarah, all of them together, feeling bad for our generation, facing a strange virus we don’t even know, saying Yizkor in our hearts.

I hope you noticed that instead of fruit soup, which I always make on Pesach, I made it thicker, like compote, in your honor. Fruit soup is too American for someone like you.

Anyhow, this morning I got a call from Yaakov, Mr. Feder’s son-in-law, and he told me that having a full-time cook right now isn’t necessary, it was just for Pesach, when they had no choice. The regular chef isn’t coming back either, because there are just a few people here now. With no surgeries, there won’t be any new residents, so they’re going to order meals from a caterer in Lakewood, who will deliver.

He thanked me.

I should thank him. This was a nice Yom Tov. Nicer than I could have imagined.

PL

Friday morning, Isru Chag, was hectic, the children calling and FaceTiming and insisting he tell them things, how was Yom Tov, how did he manage, what was the plan, how was his hip feeling.

He wasn’t very chatty, though, and Blimie turned serious.

“Tatty, we need to talk.”

Fendelsky the architect had asked Phyllis out again, even though she’d barely spoken at dinner.

He wanted to go see Gunpowder Falls. They were supposed to be mesmerizing, he said, that’s what he’d heard around the office.

She might have said yes, but once he said they were mesmerizing, she knew that she would have to stand there quietly and pretend to be mesmerized even if she wasn’t, to whisper “wow” and “spellbinding” until both their feet hurt.

So she said no. She didn’t want to be mesmerized, and that’s when it ended.

This morning, she’d been on the balcony and she sensed that the ocean looked different, but she didn’t know why. Then she realized that it was the quiet, the sheer quiet. No boats. Nothing on the horizon. No color or movement. It lay there, flat like paper, waiting for someone to draw a picture.

Even a crude, childish, crayon-made sailboat would do.

And then Phyllis found that she wanted to write this thought to Mr. Lemberger, because it was sort of mesmerizing. She wanted to show him what she meant.

Blimie was prepared to talk to her father. She didn’t need any notes.

On Motzaei Yom Tov, the siblings chat had been active. It was time, Blimie decided, a year and a half was enough and this Yom Tov had been a nightmare for Tatty.

Suri had the list from Mrs. Kempinsky, filled with big names, yichus and money and prestige.

“Good. Tatty has standards,” Blimie maintained. “He’s used to upper class, he can’t just marry anyone.”

Suri disagreed. “Tatty won’t want to move, or even change his schedule, and I don’t think he needs someone high maintenance.”

Henny agreed with both of them, as she always did, making no one happy, but at least they all concurred that Blimie would be the one to call him.

On Friday morning, she told him just this last part, sounding like a flight attendant rearranging passengers.

So Tatty, just as soon as this dreadful virus ends and we can see you, we’ll go through the names and find the right one. We all think it’s the right time.

And, without stopping for breath, she said. We all miss Mommy. We miss her so much. But life has to go on and you can’t be alone.

And because she was the oldest and could get away with it, she said, Tatty, you know you’re quite a catch, right?

Later, she would tell her sisters that he hadn’t rejected it, but he also didn’t sound eager. It was more like he was amused, or maybe distracted. They would have to do it in person.

She finished her pitch and he said, “Hmmmmm…” as if he was thinking.

He was thinking. He was looking out at the waves and listening for footsteps in the hallway and writing, a piece of paper half-filled in front of him, a shaft of sunlight painting the top of the page yellow.

It was a special Yom Tov, he’d written.

The compote was good, but it could have used a bit of cinnamon.

Then he drew a smiley face and wrote, You’ll learn.

“Okay, Blima’le,” he said warmly, “I hear you. Yes, I agree, it’s time.”

(Originally featured in Calligraphy, Issue 830)

Oops! We could not locate your form.