Light Years Away: Chapter 40

Oof! Why doesn’t she have any connections to wealthy donors? Doesn’t anybody have a philanthropic fund tucked away somewhere?

“It just makes more sense.”

“Ha’adam lo nivra ela lehis’anag al Hashem,” Shua quotes. “We’re meant to take pleasure in knowing Hashem. It sounds like maybe you’re only relating to the lehis’anag part.”

“Why?” she protests. “What could be more of a gilui Shechinah than the ocean?”

And what could more of a gilui Shechinah than that moment at 5 a.m. when Shua said to her, “Come, I ordered a taxi. It’s coming in ten minutes. You said you wanted to go to the beach on Friday morning, no?”

They drive to a beach somewhere along the coast, she has no idea where. Somewhere south of Gush Dan, perhaps. On the way, they try to think of a way to get hold of 30,000 shekels. They roll the number on their tongue. Shua doesn’t want to take a bank loan.

“You run into all kinds of ribbis problems that way,” he says. “I don’t want to rely on a heter iska.”

She remembers the days when he used to take a small gemach loan, enough to keep them out of overdraft, and run straight to the bank to deposit it. They couldn’t owe anything to the bank, because of ribbis. Once, when a neighbor heard about this rush to get to the bank before their balance dropped into the red, she’d said to Nechami, “But you’re taking it too far!” Nechami had just laughed.

“How about taking a gemach loan?” she suggests now.

“No gemach will give a loan that big. And the real issue is, if you borrow money, you have to pay it back.”

She stretches her mind, trying to think. Who does she know that might be a potential donor?

“Maybe I’ll try asking the men at kollel,” Shua says. “You never know — sometimes an avreich who looks just like all the others turns out to be the son-in-law of a big gvir.”

“No way are you becoming a schnorrer,” she says, adamant. “You’re not going to go from one person to the next, collecting coins in a plastic bag.”

Her husband laughs. “There are some very choshuve avreichim who collect money. Doing bad things is shameful. Collecting tzedakah to help a Yid? That’s an honor.”

“An honor I’d rather you forgo,” she says. Now she’s tense. Oof! Why doesn’t she have any connections to wealthy donors? Doesn’t anybody have a philanthropic fund tucked away somewhere?

“How about speaking to Gunter?” Shua suddenly suggests.

“What?”

“Gunter. Nu. The firm you work with.”

“I’d be mortified!” Nechami says.

“Why? It’s nothing to be ashamed of,” Shua says, unflappable as ever. “You call her up and say, someone we know well needs urgent medical care in America, and we’re soliciting donations to cover the expenses. It’s all tax-deductible, with receipts for whoever wants. Use the word ‘fundraising,’ not ‘collecting.’”

The idea horrifies her. It’s one thing to sit with your brothers in a formal meeting, to be convinced that you have to help Gedalya, and to commit to raising a nice sum. It’s quite another thing to start making appeals to an architect you work with, to neighbors and friends and relatives…

“I can try raising a little at the moshav,” Shua muses out loud.

From who, she wonders. They’re all simple, hardworking people there, barely managing to marry off children. Any maaser money they have is probably already spoken for.

- ••

“It’s lucky for you everyone in this family is bad at math,” Chaya had said with a laugh last night. “Because if you add up all the amounts you committed to, it doesn’t even come to 200,000.”

“Really?” Nechami was chagrined. She checked again. Shifra’s brothers had each set a goal of 10,000 — that made twenty. Tzvi had said he’d bring in forty. She and Shua had pledged thirty (how, she had no idea). Dudi and Yaffa’le had surprised them all when they’d also pledged thirty, and Yoeli had said he’d do his best, but Tzfas wasn’t a wealthy place, and he doubted he could bring in more than twenty — on a good day.

“Worst case,” he’d laughed, “I’ll go collecting in Meron.” But even that laugh had frozen on his face when he’d realized what he’d said.

“That’s 140, if everybody reaches their goal,” said Chaya. “And Abba and Ima promised to take out a loan of 25,000, so that brings it to 165. Gedalya needs a quarter million. We’re short by a lot.”

“What do you have to offer?” Nechami asked.

“Not much.” Chaya shrugged. “But let’s say 5,000. All my maaser for the next year.”

“But you’re a kallah!” Nechami bristled. “You need that money. And your apartment needs renovating. Even if we do a lot of the work ourselves, you have to take into account that the materials are expensive, and the tools, and shelves, and lighting fixtures, and all the little things that add up…”

“You have to take into account that I know all that,” her sister the kallah informed her. “Think back. Who came and painted your office with you?”

“And don’t forget that Abba and Ima’s budget is very limited.” Nechami pressed onward.

“Ooh, I was forgetting that! Good thing you reminded me!”

Nechami had to smile at Chaya’s sarcasm. “Right? Otherwise you might wander into one of those exclusive bridal boutiques and order a gown for $5,000.”

- ••

“You’re not even asking what city we’re in,” Shua comments, exhaling a bit heavily as he drags two plastic deck chairs onto their little patch of sand and water. There’s no one else around, just the two of them, and the cold of early Shevat.

“Right, I’m not asking,” Nechami agrees.

She sits down and gets comfortable as a pleasant dampness sends a tremor through her. Ah, the smell of the ocean. There’s no doubt in her mind now that people should spend more time on the beach and less in the office. This is where human beings really belong. It’s relaxing, it’s pleasant, and you don’t have to sit hunched over a computer, working.

“All right,” Shua says. “If that’s the way you want it.”

“Even when I flew to Europe with Beri, I didn’t ask which city I was going to. You remember?”

“When you flew to Europe with Beri…” he searches his memory. “He was a baby then, right? It was someplace in Slovenia, no?”

“It was someplace in Slovenia,” she confirms. “I had to at least know what country I was flying to, so I wouldn’t get on a flight to Antarctica by mistake. But that was all I knew. I didn’t want to know more than that.”

How could she ever explain it to him, ever tell him about those long, long streets she walked, lined up and down with what looked like Playmobil houses. And the old woman with the apple tree.

Shua’s brow is furrowed. “Why would a person not want to know where he is?” He picks up a little shell and throws it into the water in a wide arc. Like a little boy, he enjoys seeing the water jump in surprise.

It all comes back to her in a rush. The nights. The days. The mornings. The asthma. The endless teething, the crying, the vomiting, and the long, long trail of sleep deprivation.

“It was so hard for me when the kids were little,” she says suddenly.

“Maybe we should’ve gotten more help,” he says, with the wisdom of ten years’ hindsight. He’s a man. If you tell him that somebody died, his first response will be to start looking for a gravedigger, instead of crying with you.

And the ear infections. And the nightmares. Oy, those nightmares of Bentzi’s! She laughs suddenly, a harsh laugh.

“What’s so funny?” he asks.

“Back when I was still working at Gunter as an employee, the Internet would go down pretty often, and we’d all have to stop working until it came back, because we were on a network. And if we tried to open our email, this duck would appear.”

“A duck?”

“Yes, this primitive, pixel-y sort of animated duck, in black and white, would appear on the screen with a message that there’s no Internet and we should check the router.”

That was back before the business grew and moved to a proper office building in Har Hotzvim, back when it was still in an apartment building, and every day at one o’clock, aromas of soup and schnitzel and fried onions would drift up from the neighbors.

“One day, Chedvi accidentally pressed the space bar,” she told Shua, “and the duck started running across the screen. That’s when we found out it was a game the programmers had put in just for fun, to give the workers something to do while the network was down. It was a very dumb game — nobody would play it today with those low-res, black-and-white graphics. Cactuses would pop up in front of the duck, and you had to make it jump over them. And then they started coming faster and faster…”

“They started coming faster?” Shua repeats. It wasn’t just a duck running there, all breathless, that Nechami was describing with such passion. Maybe it was a mother duck running, jumping over obstacles, trying to win a race that never ended.

“Yes. And sometimes birds would appear, too, and the duck had to run under them when they flew low, and still keep jumping over the cactuses. But sometimes a bird would fly really low, and then the duck had to jump over it. Chedvi and Shira used to play it and compete for the highest score, but I couldn’t handle that game. I felt sorry for the poor duck… it couldn’t stop running and jumping for a second. It never had a moment to catch its breath.”

“The game wouldn’t let you stop for a second?” Shua asked.

“No. If your duck stopped, it would crash right into a cactus, and the game would be over.”

She remembers those years. Jump! Jump! Ju-u-m-mp! Dishes! Laundry! Doctor’s appointment! Orthopedist appointment! Physiotherapy! Buy screws! Fix the door! Cook! Laundry! Cook wash dry fold! A bird! Run! Here it comes — head down!

“And after you completed the first level,” Nechami continued, “the background would start changing from day to night. The background would turn black”—why was she crying?—“and the duck would turn white, and it had to keep running all night in the dark, and then the screen would turn back to day and the duck would still be running, day and night, and day and night.”

“Would the duck have liked to switch to a different game, do you think?” Shua stares at the ocean. But he’s talking to her, he understands what she’s really saying. She knows it.

“No,” Nechami says firmly. “The duck wanted that game, it chose that game. But it was hard. And that’s not a contradiction at all. People do things that are hard, and they do it by choice.”

“Hmm,” Shua says. “Was there ever an end to the game?”

Nechami sighs. “It ended one day when Odelia Gunter found out about it. She wasn’t pleased, and she said she’d find other tasks for us to do the next time the network went down. We could sort invoices or go on errands, as long as we weren’t wasting company time. And then at some point, she just brought in a technician to upgrade the whole system.”

And later on, they moved the office to Har Hotzvim. And I stopped being a salaried worker and went freelance. My four little tots grew into three fine young boys and one wonderful girl. Today they’ll dress Yossi and Yehudit and take them to preschool while I sit and stare at the ocean. Now the mother duck can pause the game and take an early morning trip to the beach.

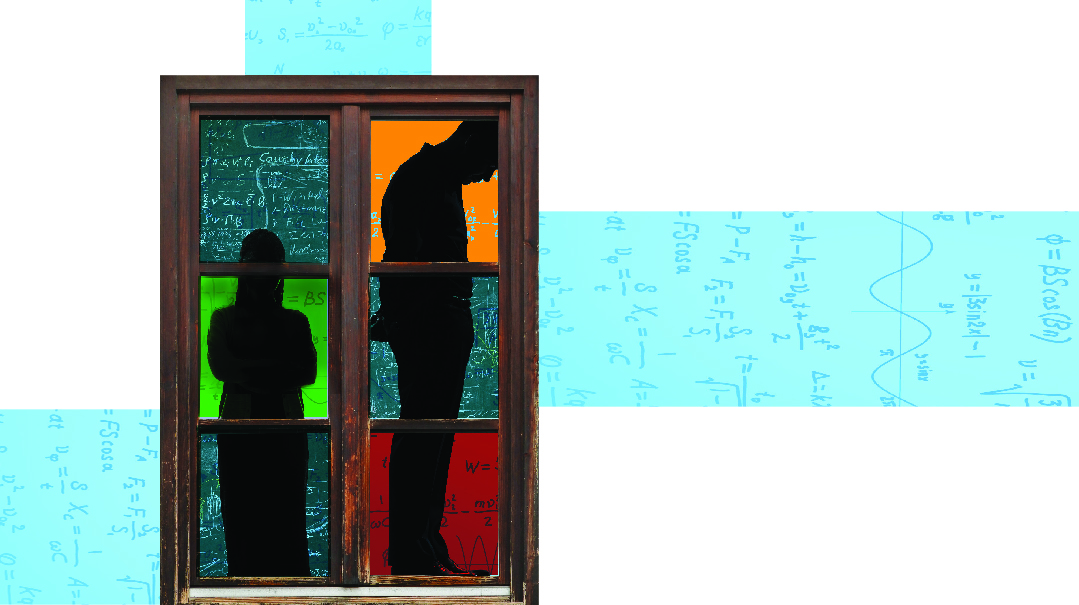

Shua lays his tefillin. He says Korbanos. With her eyes, she captures the image. The tallis, the horizon separating water from water, the two chairs. In a little while he’ll leave her here to relax some more, while he finds a shul with a minyan. And then he’ll come back and tell her it’s time to go. He has a chavrusa at nine.

to be continued…

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 884)

Oops! We could not locate your form.