Light Years Away: Chapter 21

“It’s something I’ve tried to avoid. Something I didn’t want to have in our house at all. But it looks like it can’t be avoided any longer”

Tovi

In my room, I poured a little puddle of white glue right onto the smooth surface of the desk.

It reminded me of that day in Tishrei a long time ago. I was seven or eight, and Dudi was a bochur. I was fixing a decoration for Savta’s succah, gluing back some stones that had fallen off a mosaic. And the whole time, we were arguing about the glue.

Dudi kept trying to explain to me that it was a plastic substance, and I kept saying it wasn’t plastic, it was glue. He said no, he meant plastic as an adjective, not a noun. It was a concept in physics, he said. I had no idea what he was talking about, and his explanations were only making it more confusing.

“I don’t care,” I told him. “To me, it’s just white glue, and I just want to get this succah decoration fixed. Why won’t you let me call it white glue like everybody else calls it?”

“You can call it whatever you want,” he said. “You can call it cock-a-doodle-doo, for all I care. I’m just trying to explain to you about plasticity….”

Saba and Savta overheard us from the living room and started laughing. “That should be the most serious issue you ever have to fight about,” Saba blessed us.

Dudi lowered his tone, but he kept it up for what seemed like an hour, until I finally understood about the wonderful quality of plasticity. And now, as I looked at the round puddle of glue on the desk, I realized it was a useful concept after all, and I smiled.

By the time the glue was dry, Sari and Chaiky were bathed and in their pajamas. They looked on curiously as I took out a piece of stationery decorated with a cute teddy bear. I peeled the circle of glue, which was transparent now, off the desk, placed it on the paper, and started tracing around the teddy bear with a black marker.

“You’re making a teddy bear out of glue!” Suri observed.

“Yup,” I said, and started filling in the eyes. “I can do that because it’s a plastic substance. Plastic substances are things like playdough — they change their shape when you press on them.”

Dudi’s whole explanation was replaying now in my head as I colored the right ear and then the left. “They’re the opposite of elastic substances. You can pull and stretch an elastic substance, but afterward it’ll go back to the way it was.”

“Like a rubber band?” asked Chaiky. “When I pull a rubber band, it gets long and skinny — but then it pops back when I let go.”

“Right.” My bear was all colored now. I took my school scissors and carefully cut out the shape.

“Could I have that teddy bear?” Chaiky begged.

“No, this one’s for me. But if you want, I can make more tomorrow for both of you.”

I took off my hairband. My little sisters were staring with big eyes. I put my hearing aid down on the desk and tried placing the colorful plastic teddy over it. It looked cute. A little bit of hot glue would probably do the job.

“You’re gluing the teddy bear to your hearing device?” Suri asked. “But nobody will see it anyway when it’s hidden inside the hairband.”

“I’m just trying something,” I said. “And I can’t hear you so well without the device, so don’t talk to me now, okay?”

She closed her mouth and fell into reverent silence.

I went to look at myself in the bathroom mirror. There I was — Tovi, without a band covering the place where I had no ear. And there was my hearing device for the world to see, flaunting its decoration. I tried smiling at my reflection. But… I didn’t really like what I saw. I pulled off the plastic bear, put the hearing aid back in its hiding place, and stretched the band around my head. Back to normal. Now I was the old Tovi again, and I liked what I saw.

Good old normal Tovi went to the kitchen now with the teddy bear in her pocket. Abba wanted to talk to us kids. He tried to smile, but we could see he was very serious.

“There’s something I have to tell you, kinderlach,” he said. “It’s something I’ve tried to avoid. Something I didn’t want to have in our house at all. But it looks like it can’t be avoided any longer.”

Chaimke and I looked at each other, and then our eyes met Yosef Tzvi’s, in a triangle of confusion. My hand groped the teddy bear in my pocket. What…?

“We’ve consulted daas Toireh.” Again, Abba tried to smile, but it came out really awkward. “And we got a brachah that no harm should come of it.”

Yosef Tzvi looked so mystified. “Are we getting some kind of strange pet?” he asked. “Like an orangutan or something?”

Abba and Ima gaped at him for a moment, and then they laughed and laughed.

“No, tatteleh,” said Ima. “Abba isn’t talking about an animal. He’s getting a computer for his job, and he’ll be the only one using it.”

“But we’re a no-computer family!” I blurted. Having no computer at home was part of my identity. All my friends knew that Tovi Silver’s family refused on principle to have a computer, and that even in the office, her father worked with pen and paper rather than touch a computer. What was I going to tell them now?

“Up until now we’ve had no computer,” Abba corrected me. “We’re still the same family, but now our circumstances have changed, and there will be a computer in the house, which I will use to receive and send the material I review. The only reason I’m telling you this is because at some point I’m sure you’ll notice it — even though I plan to keep it locked away in my work corner — and I don’t want you to be shocked.”

“So what are we supposed to tell people?” Chaimke asked. Just what I wanted to know.

Ima smiled at him. “You don’t have to tell them anything.”

I could hardly breathe. I waited for the boys to go away, and then I said to Ima, “Ima, I always told everyone we don’t have a computer.” Again, I felt the teddy bear in my pocket, and I thought of plasticity. If you put pressure on a plastic substance, its form changes. It becomes… something else.

“So from now on, you won’t tell them that anymore,” Ima said. She didn’t look perturbed at all. “It isn’t anybody’s business, anyway, what we have or don’t have in our house.”

Suddenly I had a scary thought. This was for sure because of me! A while ago Abba’s employers had offered him a 2,000-shekel raise if he would start working on a computer, and he had refused. But now he needed that money badly, to pay for my surgery. He wouldn’t sell his principles for money… but maybe he’d sell them to get his daughter an ear?

- ••

Bentzi, Nechami’s oldest, comes down to her office. He pulls up one of the cute little armchairs so he can see the computer screen.

“I want to watch you work,” he says. “Just for a few minutes, then I’ll go up to bed.”

“Just like when you were three,” she says, smiling at him. “Before we renovated the apartment. I used to work in the living room then, remember? And you would pull up a little chair and sit there with your teddy, your duck, and your bunny, watching me work.”

“I don’t remember,” Bentzi says, looking troubled for a second.

But she remembers. The long nights. In the summer, the air conditioner hummed over her head. In the winter, the rain beat against the window. And she, the only person in the house above the age of four, would sit and work. She loved having little Bentzi next to her, snuggled up with his stuffed animals like a little man-cub. His big eyes watched, entranced, as her sketches took form on the screen. And she loved the sound of his soft, even breaths when he fell asleep in his chair.

“I wasn’t freelancing then. I would go out to an office every day. And I was always missing work hours. I would make them up at night so they wouldn’t dock my salary,” she relates, as if lightly reminiscing. You were short a few hours, so you’d make them up at night when you should have been sleeping. There’d be interruptions, of course, when Chanochi started crying and Beri started wailing. But lots of women do it. They work, they raise children, they make up missing work hours at night. The movements of her fingers on the mouse are slower now, less focused.

“And Chanochi used to have asthma sometimes, right?” Bentzi recalls. “He would wake up coughing, and you’d give him medicine from his inhaler.”

“Yes. And Beri kept getting all kinds of visitors. Mosquitoes, worms… he was just nine months old when I first found a louse on his head. I almost fainted — yech!”

She laughs, laughs with her bechor, this gentle boy who’s grown into a fine young man. When she was raising all those little ones, everyone told her the time would come when she’d miss those days. But now when she remembers them, tears come to her eyes — and they’re not tears of joy or nostalgia.

“There is one thing I remember,” Bentzi says, looking down and scratching his forehead. “Actually… I’ve been wanting to ask you about it, Ima. I’m not even sure if it really happened… it might have been a dream.”

“Ask, my son, ask,” she says, patient as Hillel, while her hands start sketching an interior. Three walls. Pull and click. Click. Click.

Nothing prepares her for what’s coming next.

“There was one night when it was raining hard, and it was cold,” he says. “Beri was crying, and so was Chanochi. I got up and tried to give them their pacifiers, but they wouldn’t take them. And suddenly I saw you…”

“What?” She’s in suspense, not knowing what incident he’s referring to. There were so many nights like that.

He spreads out his arms. “It’s going to sound so weird. You were lying on the floor, asleep. I tried to wake you up, but you were… out cold. So I took—”

So you thought you were alone that night? There was a little boy there with you. He remembers it, he knows what happened — but he still doesn’t understand what he was seeing.

“I took a schnitzel hammer from the kitchen drawer, and I knocked on your head with it. Carefully, so it wouldn’t hurt. That’s what I remember, at least… but could it be true?”

Nechami doesn’t answer.

“After that, all I know is we were at Savta Silver’s house. That’s why I think it may have been a dream…. She tucked me into bed there and I went to sleep.”

In the morning, when they took a taxi back home, she didn’t know why there was a schnitzel hammer on the floor. It took a while for the fog to clear. And she thanked Hashem that Bentzi, gentle little soul that he was, had only used the blunt side.

“It wasn’t a dream,” she says to him lightly. “I know that night you’re talking about. I was feeling very sick, and I must have fainted. You managed to wake me up enough that I could call a taxi and take you all to Savta.”

“Ah, so that’s what happened.” He’s relieved.

She isn’t. Truth established, her son the talmid chacham can relax and go to bed on time. Nothing in his world, in his mind, has changed or suffered — all is peaceful, as it should be.

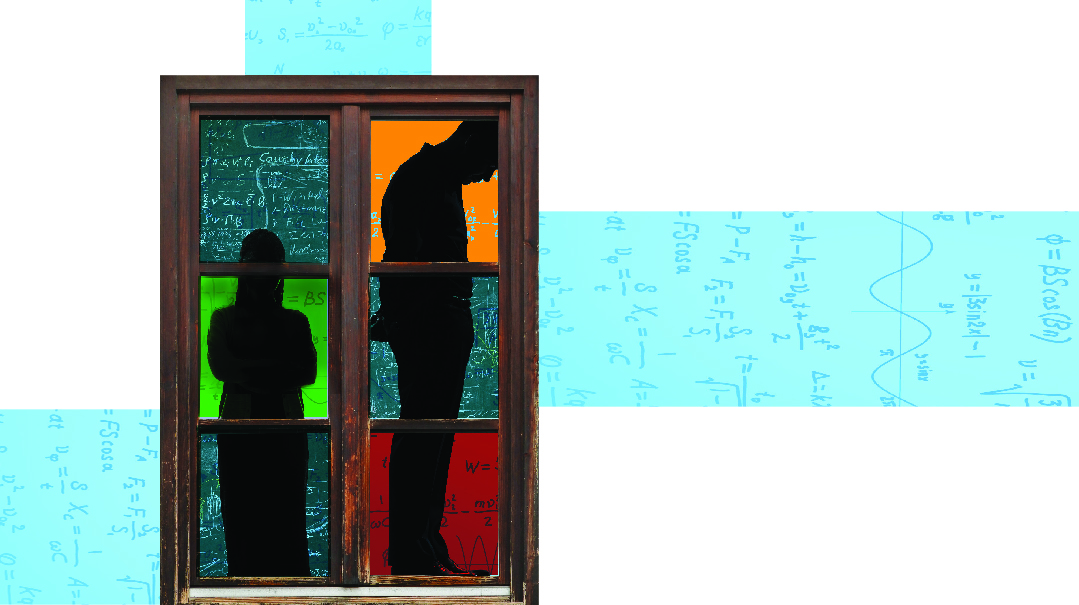

Some materials are plastic, Dudi once explained to her, and some are elastic. Either the material goes back to its original form, or it changes under pressure.

Except for materials that are too rigid. They just break.

No one told her that. She figured it out for herself.

to be continued…

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 865)

Oops! We could not locate your form.