In Sync

“I’m— the drums aren’t toys,” he says, almost defensively. “They’re— I can’t have anyone touching them. I think I’ll have to keep the study door locked, I should have thought of that already.”

T here is a series of erratic thuds coming from the downstairs study. Disturbing. Mendel looks up from his sefer finger tightening over the place.

It couldn’t be—

A clatter like something (something?!) has fallen to the tiled floor. Mendel bolts to his feet.

“Esther? Who’s in the study?”

From the kitchen running water and the hum of the microwave preclude any reply. Leaving the question hanging in the air he dashes down to the basement to find out for himself.

There is no one in the house. Only him and Esther Chaim and Gittel — and of course Yisroel Meir.

Yisroel Meir.

No.

He staggers to a halt at the entrance to the study panting hard. He is too old to run like this.

He peers into the seforim-lined room his gaze taking in the table to one side the enormous drum set holding its place of pride in the center — and the invader who has no right to be there.

“Hey! What are you doing?”

His grandson looks up startled but does not loosen his hold on one drumstick. The other is vibrating quietly against the floor sound dying in the silence.

“Let go of that, Yisroel Meir.” He tries to regulate his tone, but it doesn’t work. The little boy looks at him out of slanting eyes. “Give it to Zeidy.”

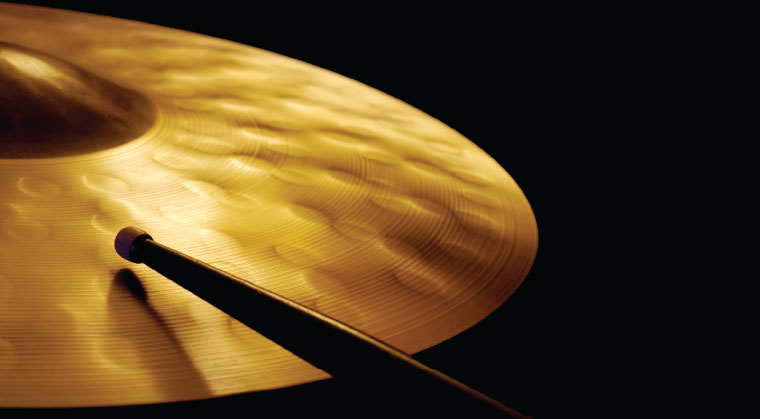

“Wanna play.” Suiting action to the first words Mendel has heard him say since last night’s arrival, Yisroel Meir gives a hefty bang on the cymbals. Sound crashes, reverberating through the study.

“No!” Mendel tugs the drumstick from his grandson’s hand. “You mustn’t touch Zeidy’s drums, okay? They’re — they’re expensive, and Zeidy needs them.”

Yisroel Meir’s face crumples and his back goes rigid. Bad move. He should’ve remembered — Esther has explained this to him, about children with Down Syndrome, the resisting stubbornness that Chaim and Gittel insist on calling endearing. (“Look at his perseverance,” Gittel had once gushed, while Esther mm-hmmed eagerly and Mendel blinked and gave a short nod, just in case anyone was looking.)

“WANNA PLAY!”

Footsteps pound the stairs, and his son-in-law appears.

“What’s going on? Ta?” Chaim takes three quick steps into the room and his eyes flicker in understanding. “Yisroel Meir, come up to the kitchen, Bubby’s prepared something yummy for you!”

“But I wanna play DRUMS!”

Chaim crouches down beside his son. “Yes, tzaddik, I know you do. We can ask Zeidy, nicely, after we eat lunch. But now there’s a yummy surprise waiting upstairs, and Zeidy’s busy now… are you?”

Mendel coughs. So he’s the bad one now, is he.

“I’m— the drums aren’t toys,” he says, almost defensively. “They’re— I can’t have anyone touching them. I think I’ll have to keep the study door locked, I should have thought of that already.”

There is a flash of hurt on his son-in-law’s face before Chaim returns his full attention to the monumental task of coaxing Yisroel Meir up the stairs.

Mendel bends to pick up the fallen drumstick. A faint headache that has nothing to do with the banging of earlier on is coming.

“Maybe we can buy him a set of toy drums, a Yom Tov present or something,” he calls after them. Neither his son-in-law nor his grandson looks back.

***

It’s less than an hour after Havdalah, two days’ worth of dishes need drying, and Heshy has insisted on a full orchestra rehearsal. He gets it; this Chol Hamoed concert is their biggest event yet, they have to be more than perfect, but still. Mendel rubs his arms — the hall is cold, apparently the heating has only just been switched on — and thinks of Esther, frying something in the kitchen. A late-night treat for the adults. He hopes there’s something left by the time he gets back.

“Guys, are we ready?”

Heshy looks fresh and energized, shirtsleeves rolled up and baton in hand.

“Give us a second, will you?” Gersh, on the keyboard, mutters, fiddling with a wire. Someone toots a quick scale on the flute — up an octave, down again.

“Come on, let’s go!” Heshy claps his hands together twice. “On the count of three—”

Mendel brings down his drumstick on the beat. The resonance of the full orchestra bursts forth. He tries to pound life into the melody, but the sound of his instrument is jarring against the music.

Something is wrong.

A key change. Mendel glances up, Heshy is waving his arms like he’s pumping the music from a well, and no one else notices the off sound from his corner.

Keeping a steady beat with his left hand, Mendel reaches behind him. He needs to tighten the screws; someone has messed with the bass drum and the floor tom and who knows what else, and as the pace quickens and his beat lags a fraction of a second behind the rest, Mendel feels the anger start to pulse, faster, faster.

Someone has messed with his drums.

There’s not a question in his mind who it can be.

He can’t keep up the beat while tuning the drums. He should wait till a break between songs, but knowing Heshy, that won’t happen anytime soon. And the sound is grating on his ears, so awkwardly off.

He plays one more drumroll, trying not to wince, and lets a crash from the cymbals fill the air. Then he slips the drumstick from his hand, bends down, and deftly applies his drum key to the screws.

Bass drum, floor—

“Hold it, guys!”

Music splutters to a halt, mid-bar. A violin screeches out into the silence, and then the note stops, abrupt. Only the cymbals are still echoing.

Heshy squints in his direction.

“Perlman! On the drums!” he roars, as if Mendel is half his age, not double, and caught bunking class again. “What’s going on?”

Mendel crawls out, stands up. “Sorry. They’re— something wasn’t tuned properly.” He runs a drumstick over the kit, hitting each piece experimentally. “They’re good to go now. Sorry.”

Heshy glares. “Seriously, guys, tune your instruments before rehearsal, we don’t have the time for this.”

It isn’t a detention with a hundred lines (I will tune my instrument before rehearsal, I will tune my instrument…), but it could’ve been. Mendel swallows a retort and looks down at the sheet music. Yisroel Meir’s too-wide smile beams in his mind.

He is fuming.

Heshy gives the count of three again, they restart from the beginning, and Moish Blauer — a newbie, looks not a day older than twenty — gives him a dirty look. Gersh rolls his eyes, at who, Mendel isn’t sure.

He brings down the drumsticks, harder than necessary, but even the steady tempo of MBD’s recently released “V’ye’esoyu” won’t pound the anger away.

***

There is a covered plate on the table, a napkin tucked beneath.

“Look what I saved you.” Esther points. She slips reading glasses off her nose and puts one of the Yom Tov magazines down. “How was the rehearsal?”

“Disaster.” He tosses keys down, heads out again to collect the rest of the drums, leaving them at the top of the stairs. Then he resumes as if he hasn’t left: “You think they’re safe here, Es? Yisroel Meir is in bed, right? The kid messed with them or something, the sound was terrible, I had to stop playing in the middle to sort them out.”

Esther makes some kind of gesture, which he takes to indicate that yes, his grandson is safely asleep upstairs, so he goes on without stopping.

“You have no idea, Heshy stopped the whole orchestra, it wasn’t fun.”

Esther nods sympathetically; she knows Heshy by now. If not for the fact that he and Gersh and Chatzkel Weinberg were the band’s first members, way before Heshy Wohl and his shiny polished baton and shiny polished shoes, he’d have jumped ship long ago.

“I locked the study door the day after they came. He must’ve done it already then. I just— you can’t— they need to supervise him better. It’s not right, he could really do damage, I mean tonight’s was repairable, but what if tomorrow—” He breaks off.

Esther sighs and pitches her voice low. “He’s just a child, Mendel. Any child would mess with an instrument…”

His eyes narrow. “Oh, yeah?”

She opens her mouth, but he waves it away. “We have five kids, Esther, five, and I’ve-lost-count-of-how-many grandchildren, and not one, not one, has ever damaged my drums. They ask before they play! They know I don’t allow anyone in there without permission! They’re— they’re not just some dollar-store junk music box. Children can know these things.” He takes a breath to steady himself. “It’s not children, it’s him, and I’m telling you that I honestly don’t know how to handle this.”

She is agitated now, her eyes flicker back and forth to the doorway, and she keeps motioning to him to lower his voice. “Stop it, Mendel, someone will hear you, it’s not nice.”

He reaches for the plate of duden. The warm, sugared delicacy flakes between his fingers. “Thanks for these,” he says, out of nowhere. “I’ll take some out to the succah, have a bite.”

The worried look doesn’t leave her eyes. Forget food.

“I’m going to bed,” he says, pushing back his chair roughly.

He is about to lift the drums when a sound from above arrests his attention. For a moment, he thinks he sees movement on the stairs to the upper floor, but the shadow has already disappeared into the darkness.

***

There is an overstuffed suitcase on the landing that hadn’t been there the night before. Mendel squints at it on the way out the door for Shacharis and shrugs. He thought the children are all here to stay for the rest of Yom Tov, but what does he know, these kinds of plans keep changing.

He comes back to a kitchen alive with noise and mess and the hullabaloo of eleven children under eight and a small selection of sleepy adults. Esther is leaning on the island in the middle of the kitchen, talking across it to Chaim and Gittel in quiet tones. They have their backs to him so he can only see Esther’s face: creased, worried, disturbed.

It looks important.

Watching them, a sudden sadness steals over his heart.

Leave them be, they’re having a serious conversation, says his mind. He ignores it.

“Gut moed,” Mendel says loudly, striding over to the group.

Gittel turns around. She’s wearing glasses, not lenses, and no makeup at all. Behind the blue plastic frames, her eyes look smaller than usual. Maybe she’s tired?

“Gut moed,” Esther says, but neither of the children answer.

“Any plans for today?”

Gittel shrugs and looks past him. Mendel taps a finger on the counter.

“Tea?” Esther asks him, flicking on the kettle without waiting for a reply.

“Heshy wants us for an hour this morning, which means at least two, but I was thinking maybe we could go on a big family trip after. To the park or somewhere. What do you think?”

“That sounds nice,” Chaim says vaguely.

Gittel gives him a look. “I’m not sure what our plans are, Ta, we might be taking Yisroel Meir out on our own.”

He can’t shake the feeling that they’re waiting for him to go. There is definitely an unfinished conversation hanging over them, like a bad smell that refuses to dissipate. The kettle whistles to a stop.

“Here’s your tea.”

It’s almost a dismissal in Esther’s tone, and it stings, but he’s not going to stay any longer where he’s not wanted.

“I’m off to the succah. Kinderlach, who’s coming with Zeidy?”

“Me! Wait for me! I’m coming!” Suri and Yanky are dancing around his feet, little Kayla patters after on unsteady legs. He feels vindicated. At least some people here want me around.

He feels Gittel’s eyes on his back, and wonders what on earth is wrong with his daughter. Maybe the stress of raising Yisroel Meir is too much for her? He wonders, suddenly, how she feels. Funny, he’s never really asked.

Mendel stops for a moment in the doorway and looks back. The grandchildren protest and try to squeeze around him into the open air, racing for the succah. Yisroel Meir is still sitting at the table, alone, eating a bowl of cereal with utmost attention. Milk slops over the sides and drips onto the table. Yisroel Meir furrows a brow with effort and tries to scrape the bowl clean. Mendel wavers.

Should he. Shouldn’t he.

Yes. No.

He looks across the room, and just then, Yisroel Meir meets his eyes. He forces a smile, but Yisroel Meir looks serious, even sad, until suddenly something shifts and, like the sun from behind storm clouds, a dimpled smile breaks through.

His heart softens.

“Yisroel Meir, would you like to come with us outside?”

Gittel flounces over to his side, hovering protectively. She takes a tissue and wipes the milky splashes away too fast, as if getting rid of them quicker will stop it having happened.

“Ta, it’s fine, he’ll eat more inside with me,” she says, and she lifts her son’s hand to wave a firm goodbye.

Yesterday, he would have been relieved to be spared, but today he is suddenly sad, like he’s missing out on something. He forces a smile even as he shuts the screen door and follows the children into the succah.

“I’m sitting on Zeidy’s lap.” Michali is waiting by the door, ready to pounce, and he laughs and pulls a chair over. She beams, little gaps and wobbly teeth and super-confident charm, and sticks out her tongue at her brothers when she thinks he’s not looking.

“Hey, no fair, you had a turn yesterday!”

Mendel pats his unoccupied knee. “C’mon Yanky, there’s room for two, and we’ll give someone else a turn soon, right Michali?”

Bentzy, of the undiagnosed ADHD, slurps his milk-with-a-few-flakes-of-cereal without a spoon, then attempts to scale the succah walls with a running jump. It’s time for some structured intervention.

“Okay, kids, let’s play Guess the Ushpizin. I’m giving clues, first one to guess gets a candy! Only to eat when you’ve finished your cereal,” he adds hastily, with a mind to indignant young mothers.

The children squeal and scrunch themselves against table and chair legs for the closest view, as if that will help them get in there first. Bentzy jumps up and down, knocking a box of tissues off the table and nearly elbowing Suri in the eye.

“Which of the Ushpizin… dreamed about a ladder?”

“Yaakov!” comes a chorus. He pronounces a draw and awards each grandchild a candy.

(“No fair,” proclaims six-year-old Yossi. “Michali never even knew the answer at all.”

“Shh, she’s little,” Yanky rolls his eyes. “And be quiet, we’ll miss the next question.”)

Mendel takes a deep breath. “Um…which of the Ushpizin… had loads and loads of guests?”

The bag empties quickly.

“Can we play another game, Zeidy?” Suri asks eagerly, when he’s finished with who was a king and which one wore a choshen and who was the second of the Avos and even which of the Ushpizin were brothers, which none of the under-six contingent could answer.

“Yeah! More games! Ball, Zeidy, let’s play ball!” Bentzy’s face is flushed, and maybe it’s the candy, but his voice is definitely louder than before. Or maybe, Mendel wonders, that’s just how it seems now in the crowded succah with so many hot and sticky little hands and faces pressing in from all sides?

He is suddenly exhausted, and the day has barely begun. And a quick glance at his watch confirms that he doesn’t have very much time to make it to Heshy’s rehearsal.

The distraction was nice while it lasted, huh?

“Sorry kids. Zeidy has to go now.” He stoops to pinch Yanky’s cheek and pat Suri on the head. “Why don’t you play a game outside, look how nice and sunny it is! And maybe we’ll go on an outing later, how’s that?”

“I wanted to sit on your lap,” pouts Chayali. “And play more games. And sing that funny song that you bounce on the words at the end.”

Mendel chuckles.

“You’ll get another chance later, sheifeleh, there’s plenty of time for lots of singing and for everyone to sit on Zeidy’s lap.”

“Michali had two turns already.”

Michali sticks out her tongue. “I’m Zeidy’s favorite, that’s why.”

“Not!”

“Am too!”

Mendel raises his voice. “All my grandchildren are my favorites. All equally. Okay?”

The children look at each other, doubtful. Then Michali shrugs, tosses her head, and says with a touch of martyr in her tone, “Okay, so we’re all the favorites.”

He is about to pat himself on the back for a job well done, and one cousin-fight prevented, when her high voice pipes up again, thoughtfully: “Except Yisroel Meir. Right, Zeidy? He’s not one of your favorites.”

“Right,” Suri nods seriously. “‘Sroel Meir never sits on your lap.”

Mendel gapes.

“O-of course that’s not true,” he manages, but the children have lost interest and are already halfway out the door. He looks around the succah, the garden, from fence to fence and back again. Would Yisroel Meir join them? Had he played with the rest of the children, each day of Yom Tov?

All this time they had spent as a family, and he can’t even remember.

***

The kitchen is empty when he steps inside, and eerily quiet. Where’s Esther?

Twenty minutes till rehearsal, that gives a few minutes to check the drums, pack them up, drive over, and set up in the concert hall.

Maybe he could even leave them there till tonight? That would be perfect — much less packing and unpacking. He’d have to ask Heshy if they would be safe.

He thinks of Yisroel Meir and grimaces. They aren’t all that safe here, apparently, either.

In the front hallway, Mendel sees the suitcases again. There are two of them now. A sense of foreboding creeps down his neck and wraps a chill around his chest.

“Esther? Whose cases are these?”

There are footsteps from the landing above, but when he tilts his head back to see, it’s not Esther looking down at him from the top stair, but Gittel.

“They’re our suitcases, Ta.”

She speaks softly, but her words are arrows.

“I thought you were staying all Yom Tov.”

“Our plans changed. We’re going to Chaim’s parents for the rest of Yom Tov.”

She’s acting so strange, so cold and un-Gittel-ish.

“Why?” he asks, and he can’t help the pleading tone. “What’s going on?”

Maybe it’s the vulnerability that does it, but suddenly she is downstairs and facing him, and there is raw anger in her eyes.

“Why? Why? Isn’t it obvious why?!” She closes a hand around the handle of one suitcase and wheels it back and forth, her movements jerky and agitated. “Because our child is not welcome here. Because he’s not treated the same as everyone else. Because he cries at night that none of the cousins play with him, that they all play with Zeidy and he’s not allowed to join in!”

His knee-jerk reaction is defensive. “I never said he’s not allowed to join anything.”

“But you did. You said it without saying anything. I saw at the meals, Ta, I watched! You asked Suri questions, you had Michali on your lap, you looked at Kayla’s pictures and listened to Yanky’s devar Torah, and not once — not once! — did you look in Yisroel Meir’s direction. Or ask him a question. Or what he’s learned. Or to sing.” There are tears rushing, gushing down her cheeks, twin rivers of hot pain. “He loves to sing, Ta, he’s been singing nonstop Simchas Torah songs, Hallel — he sang the whole car ride here, three hours straight.”

“I— didn’t know that,” Mendel says. “I’ve never heard him sing.”

“But that’s the whole point!” Gittel’s voice rises almost to a shriek. Chaim appears at the top of the stairs, calls her name, but she waves it away and turns back to her father. “He doesn’t sing here! He’s too scared and uncomfortable and hurt! He loves music, Ta, he’s just like you in that way. But you don’t share your music with him, you won’t let him into your world, all you see is his eyes and his funny slurred speech and that he’s a little bit clumsy and a little bit different and that’s all.”

“I know he likes the drums.”

Gittel chokes on a snort and a sob. “Yes, that’s why you lock the doors when he’s in the house. So he doesn’t ‘do any further damage.’”

His neck muscles tighten. “That’s not fair, Gittel. It’s not like we lock everything up. But the drums are valuable, and I can’t risk them being tampered with, or anything being broken.”

“Something has been broken, Ta. Yisroel Meir’s been broken. I’ve never seen him so sad since… since some kids in shul made fun of the way he talked.” Her breath catches and the abrupt stop puts a frame around the boulder of pain between them. “That’s why we’re going.”

Guilt and remorse and anger and shame vie for a hold on his heart, pound through his bloodstream, squeeze a chokehold around his brain. “Gittel, I— I’m sorry you feel like this… that he got hurt. I don’t— you didn’t say anything. He didn’t tell me….”

“Ta, it’s not something we say, it’s something we feel,” Chaim says, coming down the stairs and throwing a glance that is almost pitying in his father-in-law’s direction. “Yisroel Meir is different, he has his own needs, and we have to learn to communicate and work with him — but he’s still a child, just a child, with feelings and a heart.”

“And he loves to sing.”

Chaim nods. Gittel sniffles and Esther — when did she arrive? — hands him a tissue.

“Why is Ima sad?” The voice behind Gittel is halting, and Mendel sees Yisroel Meir making his way, a little unsteady, toward them. Gittel catches him in her arms and smiles through the tears, pressing a wet cheek into his.

“I’m feeling better now, Yisroel Meir, sweetie. You’re so sensitive and caring, aren’t you?”

Mendel wonders if that was supposed to be a barb for him. He clears his throat.

“Chaim— Gittel.” They look up. Yisroel Meir does too, and grips his mother’s arm tightly. Is that distrust in the deep-brown, slanting eyes? “I’m sorry things haven’t been great. But now that I know, maybe we can try again?”

He looks at Esther, who nods imperceptibly, her eyes wide and urging. It’s enough encouragement for him. “Please stay for the last days. It wouldn’t be complete here without you. All of you.”

There’s a breath and a wave of hope in the hesitation that follows.

Chaim casts a glance and a raised eyebrow over to his wife. “Gittel?”

“I’m— thinking,” she says, without raising her eyes. “I guess— I’m okay to give it a try. If Yisroel Meir…”

Mendel leans forward, ready to catch his grandson’s eye, but Chaim motions him away.

“Hey, Yisroel Meir,” he says, kneeling on the carpet and reaching for the little boy’s hand. “Would you like to stay here for the rest of Yom Tov? Bubby and Zeidy Perlman really want you to. And everyone will make sure to play with you, and there’ll be lots of yummy nosh like you had yesterday, remember?”

Yisroel Meir’s forehead creases. “But you said we’ll go to Zeidy Freed. You said!”

Chaim takes a deep breath. “I know we said that, Yisroel Meir, but maybe we can change our minds. It will be nice here, even nicer than before. How about it?”

Yisroel Meir looks up. Looks around. Thinks, and then jams shoulders up to ears in an obstinate gesture of refusal. Mendel’s heart sinks.

“I want to go to Zeidy Freed,” he announces. “Zeidy Freed always sings with me.”

***

So he is the problem, after all.

Mendel breathes past an ache in his chest, hearing the sound fill the empty study. Rehearsal starts soon, too soon, but he’s in no state to face Heshy and the others.

Bitterness edges up inside him.

Is it my fault that Yisroel Meir is — different? That he doesn’t talk the same, look the same, act the same… How should I have known?

He sits down behind his drums. No sense in messing up twice running; he’ll check that everything’s tuned now, before carefully packing up the pieces into his car.

The drumsticks are cool and comforting. He gives a light tap on the snare drum. A dozen beads jump and shuffle, a series of tiny heartbeats.

I remember the day he was born.

The memory jumps into his consciousness before he even realizes what it is.

Crowding around the bassinet. Gittel, pale, tired, eyes so soft. Chaim, the protective father, cradling his baby’s head with tenderness—

Esther, holding her grandson and crooning deliciously into his ears, even as the slanted eyes puckered at the edges and the little mouth opened in a tiny cry—

“Ta, would you like to hold him?”

But he doesn’t, and the silence stretches a moment too long, until the nurse says brightly, “Looks like our little prince is ready for his mama now, aren’t you, angel?” and Gittel shuffles off to feed her baby while he and Esther and Chaim stand awkwardly a moment longer, before his wife turns to unpack food and the first few inches of a barrier creep up between him and his hours-old grandson.

Mendel sighs, bringing his foot down with more force than necessary. Bang! The low-pitched boom of the bass drum echoes through the study. He gives an extra bang for emphasis.

It wasn’t as if he hadn’t tried. He’d smiled through the long-awaited bris, he’d snipped a piece of upsheren hair like the best of them, and he — well, Esther, really, but it’s both of them, isn’t it? — sends him a birthday card and gift every year.

The tom-tom drums are a quick piece of work, one try of each fills the air with deep resonance, and he’s back in the memories.

The first time Chaim and Gittel brought Yisroel Meir to stay. He’d been two years old already; medical complications and an emergency surgery at eight months had precluded a long stay at an earlier date. They don’t come often, but once a year or so, he and Esther clear out the boys’ room upstairs, Esther goes on a shopping spree for sensory toys with no choking hazards, and he — well, he does his best.

His best to talk to a child he can’t understand.

His best to interact with a child who won’t, can’t, doesn’t understand him.

His best to pretend that nothing matters, when everything does.

He brings down both drumsticks on the cymbals, in a dramatic display of frustration.

His best, it seems, isn’t good enough.

He wonders if they’ll ever come back, if Esther will blame him, if he’ll end up like the fathers in the stories whose children won’t come back home because they’ve been so hurt.

Next you’ll worry about the hespedim at your levayah. Stop panicking.

Mendel bends down, feeling a weight on his heart as he lifts the pieces of his instrument out to the car. They are all perfectly tuned. No one has touched them in the past hour, and the study door was unlocked all this time.

***

The stage lights burn and glow. A headache is starting to fill the space behind his eyes.

V’samachta, b’chagecha!

A drumroll, extended, elaborate.

His head pounds, on beat with the drums. There, there in the audience, somewhere — sit Chaim, Gittel, and Yisroel Meir. They’re leaving tonight, probably straight from the concert hall. Of course, Esther’s there too, and his other children and grandchildren — Bentzy probably jumping half out of his seat in excitement — but it’s Yisroel Meir who is on his mind now. Does he even know why they’re at this performance? Is he straining to see his Zeidy? Or has he lost even that privilege to the pain?

A vague ache squeezes his chest.

Not enough. He hasn’t done enough, he never has, and tomorrow they will be gone.

And when will he get another chance?

Heshy swings the baton wildly. Mendel is so nearly offbeat, it scares him. He tunes back into the music: intense, swirling, pouring over the crammed auditorium like so many ocean waves. He pounds the hurt, the energy, the wordless plea into his drums, but the feelings simply fill the space around him, clinging on, never letting go.

***

There is an interlude an hour and a half into the performance. Mendel thinks to take a break, but no — Taskmaster Heshy has other plans. A quick review turns into an impromptu rehearsal, and Mendel watches as the minutes tick, agonizingly, away.

In the end, their own break is a bare quarter of an hour.

Must find Yisroel Meir. Need to speak to them.

He’s not sure what he wants to say, but he has to say something, anything, and there is so little time left.

He speeds through the aisles, up, down, around. He wants to text Esther to find out where they all are, but he’s left his cell at home and there’s no time to try and borrow. Weren’t they planning to sit near the front?

The main lights begin to flicker off, and a disembodied voice request that the the audience take their seats. He needs to get back to the stage.

Where are they?!

He has to get back now. If he doesn’t want Heshy to roast him alive, anyway.

As he hurries past rows of spectators, past cheering crowds with phone cameras at the ready, his eyes flit from seat to seat, face to face.

No Yisroel Meir.

He settles into place behind his drum set. The bass and the snare and the toms, they’re old friends, reflecting every piece of his emotions back to him. Today they’re not enough, and he feels a niggle of discontent.

There is a mild commotion at the side of the stage. Several players shift in their seats, and Heshy waves his arms in a furious effort to get everyone’s attention.

“Now!”

Mendel feels warm breath on his cheek. He half-turns and there, there is his Yisroel Meir, all slanting eyes and beatific smile. And suddenly difference doesn’t matter, difference is beautiful, and nothing exists but the eyes that meet his with a wide-open gaze, a wavering of trust, a tiny sparkle.

And fear melts away as Mendel realizes that difference fades to nothingness when all hearts sing the same melody.

“Zeidy,” his grandson whispers, and above the cry of the violin there is no sweeter sound. “The music is so nice. Can I play, too?”

Their eyes meet just as the baton rushes to the heavens and music of a full orchestra bursts forth. The stage lights are bright and dazzling like a world full of stars. There is an instant, just one, before Heshy will see, before the worried parents will appear and whisper-shout across the orchestra and rescue their wandering child.

Mendel misses just one beat. Then he grabs his grandson’s hand and curls his own around it and the drumstick.

And they are playing together.

(Originally featured in Calligraphy Succos 5778)

Oops! We could not locate your form.