If Feelings Could Talk

| May 31, 2022When we find ourselves in these irrational places, it’s often our heart’s way of saying, “You need to pay attention”

If Feelings Could Talk

Sara Eisemann LMSW, ACSW

Ever have one of those days where you’re just off? Where you’re angry at the front door because it doesn’t open automatically, and really, how are you supposed to get out the door with coffee in one hand and papers in another? And then your neighbor has the nerve to say hello as you’re rushing to the car? And suddenly you find yourself bawling into your steering wheel?

When we find ourselves in these irrational places, it’s often our heart’s way of saying, “You need to pay attention.” Our feelings can’t talk, but if they did, this is what they’d say:

Sadness might be telling me I need to cry.

Loneliness might be telling me I need connection.

Shame might me telling me I need self-compassion.

Resentment might be telling me I need to be heard, and maybe, eventually, to forgive.

Emptiness might be telling me I need to do something creative.

Anger might be telling me I need to check in with my boundaries.

Anxiety might be telling me I need to b r e a t h e.

Stress might be telling me I need to take things one step at a time.

To respect our feelings, we first have to acknowledge they exist. As obvious as that sounds, it’s actually quite the challenge for a lot of us. How many times have we answered, “I’m fine,” when we’re anything but fine? Yeah, we don’t have to bare our soul to everyone who asks, but what about when we’re lying to ourselves?

Naming the correct feeling is our first step to dealing with it. And that can get tricky, because often, one feeling masks another. It’s so easy to confuse boredom with emptiness, irritability with anxiety.

The most common duo is anger and hurt. Beneath most anger is a feeling of hurt, abandonment, or betrayal. Like our protagonist in the example above, many of us might feel anger at the door or any other hapless object (and sometimes person) who gets in our way, when really, we’re sad.

Anger is empowering, it fills us with what feels like energy and strength. Therefore, we far prefer it to the deflated and unenergized feeling of sadness. We certainly prefer it to the pain of loneliness or abandonment. And we can embrace it with self-righteous indignation.

But here’s the thing: At some point, the piper must be paid. When sadness comes, she deserves to be heard. Trying to keep sadness, loss, or grief at bay only works to a point. After that, it can become misplaced anger, or worse, it can lead to total shutdown. If, however, we take the time to hear what our emotions are trying to say, and to experience the feeling, they’ll feel acknowledged and will retreat back where they belong until we need them once again.

Sara Eisemann LMSW, ACSW, is a licensed therapist, directed dating coach, and certified core mentor.

Be a Naaseh V’Nishma Parent

Dina Schoonmaker

At kabbalas haTorah, each member of Klal Yisrael received two crowns, one for the word “naaseh” and one for “nishmah.” There’s value in committing to act before knowing the details and reasons, and there’s also value in hearing the reasons after performing the action.

Naaseh before Nishma

This order is counterintuitive for us as parents — we often give our children the nishma before the naaseh. Before asking them to do something, we offer long explanations as to why we want them to do it.

We believe that a child has a “right” to know why they’re being asked to do something, and that we’re educating them and being inclusive by sharing the reasoning.

However, in a child’s mind, lengthy explanations makes it seem as if we feel guilty for asking and are offering apologies for our request.

Additionally, we’re training our children not to do something unless they understand the reasoning behind it. The child is now subservient to his intellect; not to his parent.

Pre-action, the child’s hearing capacity is minimal, and much of what we say falls on deaf ears. When we make requests of our children without providing an explanation, we implement the concept of naaseh v’nishma.

Nishma after the Naaseh

Chazal say “ein mezarzim ela es hamezurazim” — you only motivate those who are already motivated. In other words, those who are have already done something positive are eager to learn more about the benefits of their behavior. The willingness to listen, learn, and be inspired is maximal after one has already committed and acted.

Giving an explanation, story, or encouragement to a child after the action is done can be one of the greatest chinuch opportunities. Try something like, “Wow, I was having such a hard day, and seeing the table set really makes things easier.” Or tell a story about a gadol who performed a similar mitzvah.

Once a child is post-action, there’s no danger of him feeling a sense of manipulation, and his ears and heart are wide open.

Dina Schoonmaker has been teaching in Michlalah Jerusalem College for over 30 years. She gives women’s vaadim and lectures internationally on topics of personal development.

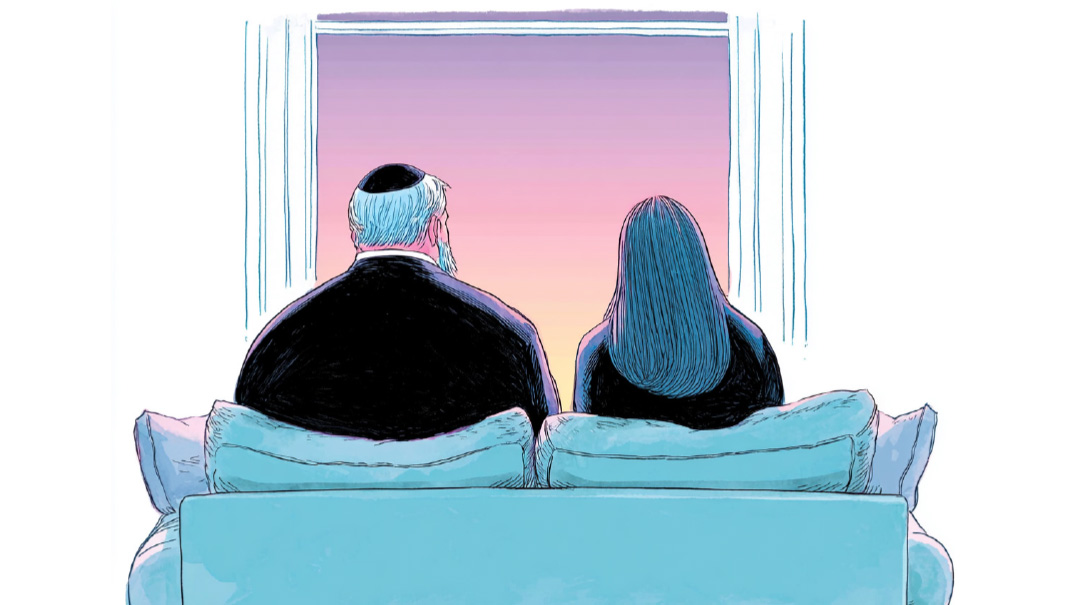

Boundaries Create Closeness

Esther Goldstein LCSW

It’s easy to feel that if we’re close to someone, we don’t need boundaries. But every healthy relationship thrives with boundaries.

We honor boundaries by respecting what others tell or show us. If you ask your mom something and she responds evasively, respect that she might not want to share with you and drop the subject.

If you want to emotionally connect but your husband isn’t up for it, accept it without nagging. Say something like, “I’m sad that we can’t connect now because I’m really feeling lonely, but I know you need your space now, and I respect that. I’m here whenever you’re ready to connect.” And then you can offer a warm smile, showing that you can honor a need and stay in connection mode even though you’re disappointed.

Boundaries essentially allow intimacy and love to grow. They convey: “I am a person with needs, wants, hopes, worries, and dreams, and you are a person, entirely separate from me. There’s space for both of us in this relationship.”

Esther Goldstein LCSW is an anxiety and trauma specialist who runs a group practice called Integrative Psychotherapy & Trauma Treatment in the Five Towns, Long Island, New York. Esther also has a trauma training program for therapists.

(Originally featured in Family First, Issue 795)

Oops! We could not locate your form.