Getting Inside Their Heads

Pediatric neurosurgeon Dr. Howard Weiner heals the smallest patients with skill, heart, and faith

The seven-year-old boy in the examining room doesn’t stop moving, fiddling with an iPad or jumping off a chair and bouncing from one family member to another. His shaggy black hair and thick, black-framed glasses hide his eyes, but it’s clear they aren’t well focused. He’s like a friendly puppy, going from person to person wagging his tail.

Dr. Howard Weiner, the chief of neurosurgery at Texas Children’s Hospital since 2016, walks in with a smile. “What’s your name?” he asks the boy. The boy responds, but he’s unintelligible. “We call him Dos,” says his mother, a spirited Hispanic woman. “He’s the second child, his sister is in college.”

Dos has Chiari malformation, a usually congenital condition in which the cerebellum bulges through the opening of the skull where it connects to the spinal column. This creates fluid buildup and/or cysts in the spinal cord, and leads to poor coordination, difficulties with swallowing, headaches, and developmental delays. Dos has apnea, and since he aspirates his food, he needs a G-tube to eat. He understands speech, but he has trouble hearing and speaking and has ADHD. Surgery is sometimes advised for such patients to relieve pressure on the spinal column, by draining fluid or repositioning the spinal cord.

Dos’s mother, who lives in a Texan town more than four hours away, was advised to pursue an operation to fuse Dos’s spine. How did she know to come to Dr. Weiner? “I looked online,” she says. “I only wanted a doctor who was rated five stars. And I have to trust the doctor. I saw Dr. Weiner’s picture and I knew right away he was someone I would like.”

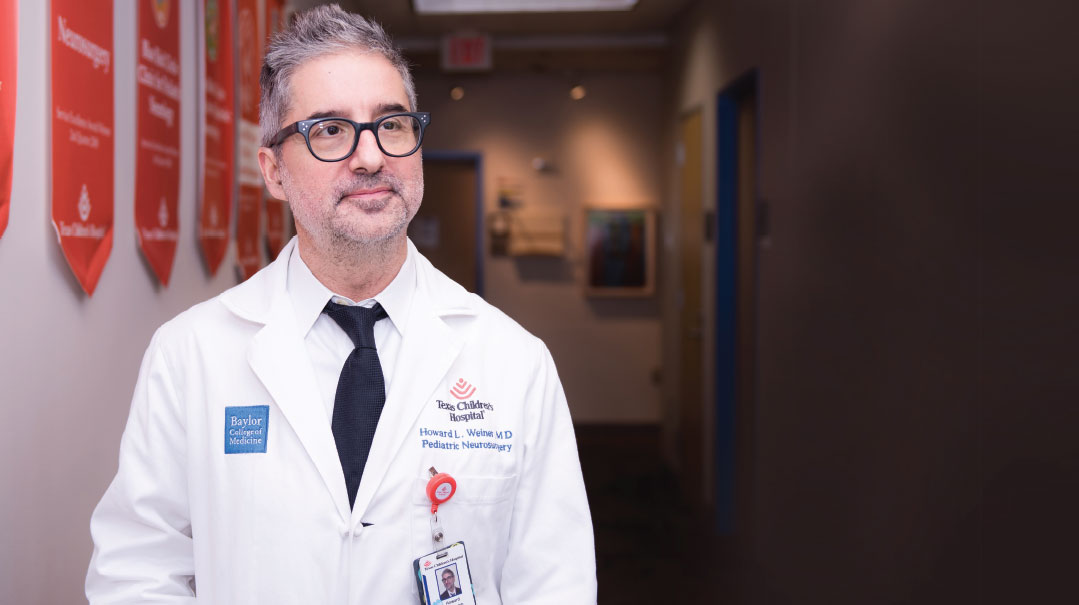

Dr. Weiner looks flattered. At 56, with black-rimmed glasses and a thick brush of salt-and-pepper hair, he has an attentive, compassionate Jewish face. His white coat is an indication of his medical authority, but the yarmulke on his head is a clear sign he answers to a Higher Authority. “I was a little worried how my kippah would be viewed in Houston, but people here respect religiosity,” he comments.

He regards Dos’s file, and asks a few more questions. Dr. Weiner isn’t convinced that surgery is the best option. “Your son didn’t get to this place in a day, and we won’t undo it in a day,” he says. “We want to be 100 percent sure surgery is the best option. I’m of the opinion that a doctor should measure twice, and cut once.

“I’m going to present Dos’s case to my team later this week,” he says. “We’ll put our heads together and let you know what we think. Are you okay with that?”

Mom nods, and he turns to the grandmother, who’s joined Dos and his mother for the visit. “I like that you’re cautious,” she says in careful English.

They have no more questions, so Dr. Weiner sweeps out of the room, retiring to a desk in the doctors’ room to dictate notes onto his computer, and exchange a few words with the nurses. “Conditions like this are extremely stressful for families,” he remarks. “Some families grow stronger, acquiring a sense of purpose and responsibility. But others are crushed; they don’t survive the crisis. It has a lot to do with how they were functioning before the crisis.” In recent times, he adds, the burgeoning of support groups and other support systems make a tremendous difference for families like Dos’s.

Dr. Weiner has only been in Houston for four years. But in that short space of time, with his warm bedside manner and evident love of people, Dr. Weiner has created a special place for himself in the hearts and minds of Houston’s youngest neurosurgery patients.

Physician Profile

The Texas Medical Center in Houston is best described as a medical metropolis. Featuring the MD Anderson Cancer Center, Baylor College of Medicine, a VA hospital and the Texas Children’s Hospital among others, the towers gleam in the Texas sun like the Emerald City as you drive up on the highway, and everywhere you look people are scurrying around in scrubs.

We first meet Dr. Weiner in his office on the 12th floor of Texas Children’s. It’s a comfortable space, embellished with framed diplomas, plaques honoring his election as a Top Doctor by New York magazine and other publications, and photos of his family on the desk. One wall is covered with homemade thank you cards from his pint-sized patients (some of who’ve grew into teens and adults thanks to his interventions) and their parents. “I have boxes and boxes of those,” he remarks. “It’s what keeps me going.

“Actually,” he continues, “patients thank you much more for being a mensch — for taking the time to take their calls, for listening to them, and showing you care — than any technical skill you might have. What matters to people is the connection they feel with their doctor, and their gratitude comes as much from the caring as the curing. Obviously an operation has to be perfect technically, but the human side is essential. The real superstars in medicine all have this quality.”

He credits his parents with instilling him with the ethos of caring for other people. His father was a Holocaust survivor; his American-born mother was a classmate of Barbra Streisand at Erasmus High School in Brooklyn. Dr. Weiner was born in the Bronx and grew up in Westchester County, and while his parents weren’t shomer Shabbos, they were staunchly traditional, sending him to a Solomon Schechter day school and later to the Ramaz School.

He had excellent teachers at Ramaz, notably Rabbi Jack Bieler and Rachel Taub Weinstein. “At Ramaz, my eyes were opened to the idea that you can be a religious Jew and still be a professional fully engaged in the world,” he says. He also absorbed the influence of his paternal grandfather’s side of the family, frum people who lived in Boro Park (one cousin is Heshy Kleinman, the author of Praying with Fire). “I inherited that religious gene,” he says.

He attended the University of Pennsylvania before enrolling at Cornell University for medical school, where he found himself pulled toward working directly with the brain, hands-on. Is he good with his hands? “Not around the house,” he says with a ready smile. “My father was very handy — he even built a shed with a workbench for himself and a small one for me when I was a child. But my manual skills are mostly confined to the operating room.”

He avows that he possesses good spatial and navigational skills, and a strong sense of judgment and safety. “In the OR, you need to know when to push limits and when to stop; the enemy of the good is the perfect. Complications happen in the last few minutes of surgery, when you’re tired and more prone to make mistakes.”

During his residency, one of his biggest mentors and influences was Dr. Fred Epstein. Epstein, the author of Gifts of Time and If I Get to Five, was a pioneer in pediatric neurosurgery and a warm, caring physician — to the point where he once allowed Mrs. Miriam Lubling a”h to pull him off a plane to Florida to operate on a child in dire straits. Epstein was always looking for new, out-of-the-box approaches to issues deemed untreatable or inoperable, and his compassion and can-do spirit left their imprint on Dr. Weiner.

Toward the end of med school, Dr. Weiner met his wife Barbara, an art student who is today an early childhood educator and docent at the Houston Museum of Fine Arts. He did his residency at NYU and stayed on for a fellowship and then as a member of the staff until 2016. There was one six-month hiatus in 1997, when he went to Paris with his wife and almost-one-year-old twins to work at the Institute of Cellular and Molecular Embryology under Dr. Nicole Le Douarin. “It was my family’s first adventure,” he quips, fondly remembering their stay in the Third Arrondissement and the wonderful kosher food in the Marais. With Dr. Le Douarin, he participated in early experiments in neuroplasticity, removing hindbrain cells in unborn chicks from one region and grafting them to another. The object was to see if the misplaced cells would adopt the functions of the new region or retain their original characteristics. “The procedure was harder than neurosurgery!” he recalls. “I finally got it down, then I had to leave.”

Spiritually Speaking

The Weiner family lived in White Plains from 2000 to 2016, where their three children attended S.A.R. [Salanter Akiba Riverdale] Academy. There they became close to Rabbi Shmuel Greenberg of Young Israel, a nephew of Rav Moshe Feinstein ztz”l, and began growing in their level of observance. “Rabbi Greenberg is still our family rav,” Dr. Weiner says. “We were part of his community for many years, and he knows every member of our family.” Dr. Weiner often serves as Rabbi Greenberg’s go-to health-care professional for medical sh’eilos.

They continue to learn together, and he also continues to learn with Rabbi Aron Rovner, whom he met over ten years ago when he began participating in an early morning adult kollel. In Houston, he’s joined Rabbi Barry Gelman’s shul.

He found himself yet another “rebbi” in Rabbi Dr. Akiva Tatz. He first met him when a colleague brought him to hear him speak at Rusk Rehabilitation, and he was “blown away.” “I bought all his books and CDs. When he came to a Gateways weekend, I went there to meet him,” he says. “I invited him to come speak at NYU, and I’d like to bring him here as well. I love the way he thinks, his spiritual approach, the way he approaches the big questions.”

By 2007, Dr. Weiner felt his level of commitment was strong enough that he wanted to begin wearing a kippah to work. He was slated to speak at a big dinner for FACES (Finding a Cure for Epilepsy and Seizures), a fundraising arm at NYU for epilepsy research and education, and hoped to start by wearing it there. “I approached Dr. Pat Kelly, who was the chairman of my department and a leader in our field. I told him, ‘My dad was in Auschwitz and Buchenwald, and I feel I have to do this.’ His response was, ‘It’s good. People will see that you stand for something.’ ”

Faith, he maintains, plays a huge role in doing neurosurgery. He recalls the tale of the chassidic master who kept a piece of paper in each pocket. One stated, “I am dust and ashes,” and the other stated, “The world was created for me.” “When you go into surgery, you have to work as if the outcome is all in your hands,” he says. “The mantra is, ‘It has to be perfect,’ and you have to remain focused and scientific. But you also have to keep in mind that it’s not all in your hands. If your ego gets in the way, it’s a problem; I’ve seen surgeons become undone by their own egos.”

He speaks with admiration of a family who helped give him perspective about his own power, and limitations, for healing patients. Their daughter was dying from a tumor in the brain stem, a region extremely difficult to operate on. There wasn’t anything the team could do to save her, and she passed away. Dr. Weiner was very upset, but the father, an Israeli dayan who’d been living in the US, wasn’t angry with him at all. He told him, “Don’t feel bad. You’re in this job because Hashem needs you to be doing it, and you should just continue to do your job.”

“I found that very beautiful,” Dr. Weiner says.

Before each surgery, he takes a moment to stand by a window, say a private prayer, and visualize the outcome he hopes to achieve. Those outcomes can be hard to predict, since the brain is still mysterious, a dark continent, in many ways. Some patients will surprise you by how well they recover; others with a better prognosis may fail. “You can do a perfect operation, and the patient doesn’t wake up,” he says.

Most of the time, he acknowledges, he’s just so busy that he doesn’t have time to dwell on the difficult outcomes. It’s when things quiet down that the emotional challenges well up. “Even when you accept that you’re not in control of everything, bad outcomes are still very hard to process,” he admits. “You take them with you every day.”

Fortunately, the sad outcomes are balanced by the nachas-bearing ones. Dr. Weiner recalls a case he saw about 20 years ago, a boy from Italy who had epilepsy with tuberous sclerosis (lesions throughout the brain that cause seizures). At the time, doctors thought surgery in such cases was too risky, and would simply throw up their hands. But this child was seizing constantly, and his mother — who’d been told her child might not survive early childhood — was determined to advocate for a new approach. Dr. Weiner and Dr. Orrin Devinsky, the director of the NYU epilepsy center, decided to break all the conventional rules of surgery, and operate to remove the lesions in several locations of the boy’s brain.

“It took treatment for this condition into a whole new direction.” Dr. Weiner says. “Today, we operate on these lesions. This boy grew up — I believe he now works as an EMT — and the family still keeps in touch. They send us vats of olive oil, and last year when my wife and I were in Rome, they came in from Florence to join us at a kosher restaurant.”

We follow Dr. Weiner down another hall to see another patient, Sophia. Sophia, a round-faced 22-month-old, wears round pink glasses and a little barrette in her black hair. Her legs are encased in braces. “How are you?” Dr. Weiner says warmly, but Sophia shrinks away from him to take shelter against her mommy, a quiet but pleasant woman with a trace of Spanish accent. “She doesn’t know you,” she apologizes with a smile, unperturbed.

Sophia was born with spina bifida, a birth defect in which the end of spinal cord fails to close or develop properly. The result includes difficulties with walking, mobility, bowel and bladder control, hydrocephalus, skin irritations and allergies, sleep apneas, and meningitis. “Spina bifida treatment is very big here at Texas Children’s,” Dr. Weiner says. “If you can detect it and treat it very early, you can prevent many of the deficits in motor development and the hydrocephalus. We have two doctors here, Michael Belfort — a Jewish doctor from South Africa and the chairman of the OB/GYN at Baylor — and William Whitehead, who perform surgeries on babies in utero to correct the defect.

“Doctors used to remove the mother’s uterus to operate on the baby, and put it back in after. It was risky to the mothers, so here they developed a minimally invasive technique to go in with a scope, like working through a straw.”

The surgery can also be done after birth, but it’s most effective before. In Sophia’s case, her mother was unable to take time away from work and her other children for the prenatal surgery and mandatory resting period afterward. Instead, Sophia received the surgery a day after birth. She’s had some motor delays, so she can only walk with assistance, although she’s going to get a walker soon. While she doesn’t speak yet, she has started to babble.

The latest ultrasound shows Sophia has a bit of urinary reflux, but she hasn’t developed any infections. Dr. Weiner gently measures her head. “The circumference looks good,” he pronounces. “I don’t see any need for a shunt.” He asks about her vision, notes the way she moves.

Mom is concerned about a large birthmark on Sophia’s back, above the incision for her surgery. Dr. Weiner offers to give her a referral to a plastic surgery colleague within the hospital, who could probably remove it when she’s a bit older. “She’s doing great — we’re very happy.” he says. “Any questions?”

“No,” Mom says. “We’re happy too.” She’ll be back in six months for the next follow-up.

Patients First

When Dr. Weiner was first proposed the job at Texas Children’s, he hesitated; he’d spent the better part of two decades at NYU, and was very happy with his job and community. Yet a colleague in Toronto told him, “Texas Children’s? You should grab it.” His wife likewise urged him to accept, telling him it would be their next big adventure. “She said it would get me out of my comfort zone and allow me to grow,” he says, “and she was right.”

They haven’t looked back. They’ve found Houston to be extremely warm and welcoming, both the Jewish and professional communities, and Dr. Weiner finds Texas Children’s a whole new frontier. It’s the largest children’s hospital in the world, and the pediatric neurosurgery department treats more challenging brain and spinal column tumors than the nearby MD Anderson Cancer Center.

“NYU was great, but here my eyes were opened up to amazing possibilities.” Dr. Weiner says. “There’s tremendous volume and intensity here, and it’s a challenge to find time for everything. But we have a great team with a very committed staff.”

It’s most rewarding when patients see significant changes in their development and quality of life. For example, one of Dr. Weiner’s specialties is the treatment of epilepsy. While epilepsy is usually treated with medicine, about a third of all cases don’t respond to medication. The majority of those who are candidates for surgery can be helped by surgical intervention, especially in cases like tuberous sclerosis, a genetic disease that leads to benign tumors that cause seizures and autism. (Autism is often seen in conjunction with other neurological conditions, such as epilepsy, that compromise the brain’s communication networks.) One of Dr. Weiner’s colleagues at Texas Children’s, Dr. Daniel Curry, garnered fame as a pioneer in laser ablation surgery for epilepsy.

“If a child is seizing often, he can’t learn, develop, or socialize. His parents are worried he’ll stop breathing,” Dr. Weiner explains. “But when you can treat the patient with surgery, you can reverse this. It’s like a light switch turns on. In the process you develop strong relationships with patients and families.”

Now at the height of his career, Dr. Weiner finds himself more able to concentrate on human relationships and the feelings of patients and staff. “When I was in training, I was so focused on reaching my goals. I was always running hard,” he says. “But you can miss things going on around you that way. It took some time after I emerged from my residency to get in touch with my real self, to reflect on what I’d learned from my parents and teachers. I’ve always been a sensitive person, but now I’m more able to tune in to the human side.”

Our last visit of the morning is with Annie, an almost-two-year-old who looks like a little china doll with her blond pixie haircut, round blue eyes, and pinafore dress. An IVF baby, Annie was born at only 25 weeks’ gestation, and developed hydrocephaly as a result. She spent four-and-a-half weeks in the NICU, and was given her first brain shunt at 29 weeks. Now, at 21 months, Annie has slight developmental delays, so she seems more like an 18-month-old. She received physical therapy for a while, but has since graduated from it.

Annie’s mom Nancy is a yoga instructor, which Dr. Weiner suggests accounts for her upbeat, unruffled personality. “I’m very centered,” she states. “Having perspective is so important.” Her positive attitude and cute baby have clearly made them favorites with the staff.

Annie had brain surgery again just two weeks ago. “She started vomiting, and I knew either it was a stomach bug or she’d need brain surgery,” Nancy says. “It wasn’t getting better, so I took her to the ER and was blessed to be assigned to Dr. Weiner.”

She was indeed fortunate, for Annie had a Grade Four brain bleed, the most serious level. She was given a new shunt, a valve on the top of the brain with a tube down to the stomach, where the excess cerebrospinal fluid is absorbed. The emergency surgery took place on a Wednesday night, and by late Thursday afternoon Annie was discharged. “The shunt will grow with her,” Dr. Weiner says. “I had patients in New York who grew up with shunts and are now college students. You just have to monitor the situation.”

Regular monitoring and testing ensure the interventions are functioning as they should, and provide measures of the sometimes-subtle changes in motor and intellectual functioning. Mothers and primary caregivers are important sources of information, as they know their children best and notice when behaviors deviate from the norm.

In pediatric neurosurgery, Dr. Weiner says, the relationship with patients and their families is critical, because most of them need to be followed throughout their lives. “The ‘one and done’ surgery is the exception, not the rule,” he says. “I’m still in touch with some patients I started with 20 years ago.”

But those relationships are what make the job so gratifying. Today, with the enormous resources and talented staff now at his disposal, Dr. Weiner is excited and thrilled at the possibilities to help patients at a whole new level. His new patients, it seems clear, are even happier.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 822)

Oops! We could not locate your form.

Comments (1)