Getting Inside Their Heads

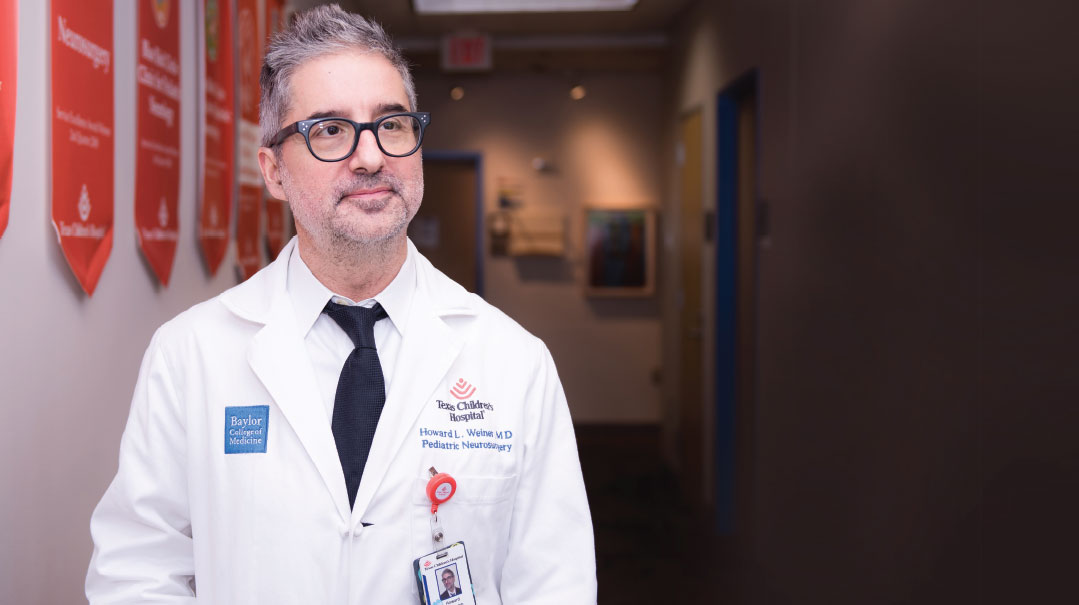

Pediatric neurosurgeon Dr. Howard Weiner heals the smallest patients with skill, heart, and faith

The seven-year-old boy in the examining room doesn’t stop moving, fiddling with an iPad or jumping off a chair and bouncing from one family member to another. His shaggy black hair and thick, black-framed glasses hide his eyes, but it’s clear they aren’t well focused. He’s like a friendly puppy, going from person to person wagging his tail.

Dr. Howard Weiner, the chief of neurosurgery at Texas Children’s Hospital since 2016, walks in with a smile. “What’s your name?” he asks the boy. The boy responds, but he’s unintelligible. “We call him Dos,” says his mother, a spirited Hispanic woman. “He’s the second child, his sister is in college.”

Dos has Chiari malformation, a usually congenital condition in which the cerebellum bulges through the opening of the skull where it connects to the spinal column. This creates fluid buildup and/or cysts in the spinal cord, and leads to poor coordination, difficulties with swallowing, headaches, and developmental delays. Dos has apnea, and since he aspirates his food, he needs a G-tube to eat. He understands speech, but he has trouble hearing and speaking and has ADHD. Surgery is sometimes advised for such patients to relieve pressure on the spinal column, by draining fluid or repositioning the spinal cord.

Dos’s mother, who lives in a Texan town more than four hours away, was advised to pursue an operation to fuse Dos’s spine. How did she know to come to Dr. Weiner? “I looked online,” she says. “I only wanted a doctor who was rated five stars. And I have to trust the doctor. I saw Dr. Weiner’s picture and I knew right away he was someone I would like.”

Dr. Weiner looks flattered. At 56, with black-rimmed glasses and a thick brush of salt-and-pepper hair, he has an attentive, compassionate Jewish face. His white coat is an indication of his medical authority, but the yarmulke on his head is a clear sign he answers to a Higher Authority. “I was a little worried how my kippah would be viewed in Houston, but people here respect religiosity,” he comments.

He regards Dos’s file, and asks a few more questions. Dr. Weiner isn’t convinced that surgery is the best option. “Your son didn’t get to this place in a day, and we won’t undo it in a day,” he says. “We want to be 100 percent sure surgery is the best option. I’m of the opinion that a doctor should measure twice, and cut once.

“I’m going to present Dos’s case to my team later this week,” he says. “We’ll put our heads together and let you know what we think. Are you okay with that?”

Mom nods, and he turns to the grandmother, who’s joined Dos and his mother for the visit. “I like that you’re cautious,” she says in careful English.

They have no more questions, so Dr. Weiner sweeps out of the room, retiring to a desk in the doctors’ room to dictate notes onto his computer, and exchange a few words with the nurses. “Conditions like this are extremely stressful for families,” he remarks. “Some families grow stronger, acquiring a sense of purpose and responsibility. But others are crushed; they don’t survive the crisis. It has a lot to do with how they were functioning before the crisis.” In recent times, he adds, the burgeoning of support groups and other support systems make a tremendous difference for families like Dos’s.

Dr. Weiner has only been in Houston for four years. But in that short space of time, with his warm bedside manner and evident love of people, Dr. Weiner has created a special place for himself in the hearts and minds of Houston’s youngest neurosurgery patients.

Oops! We could not locate your form.

Comments (1)