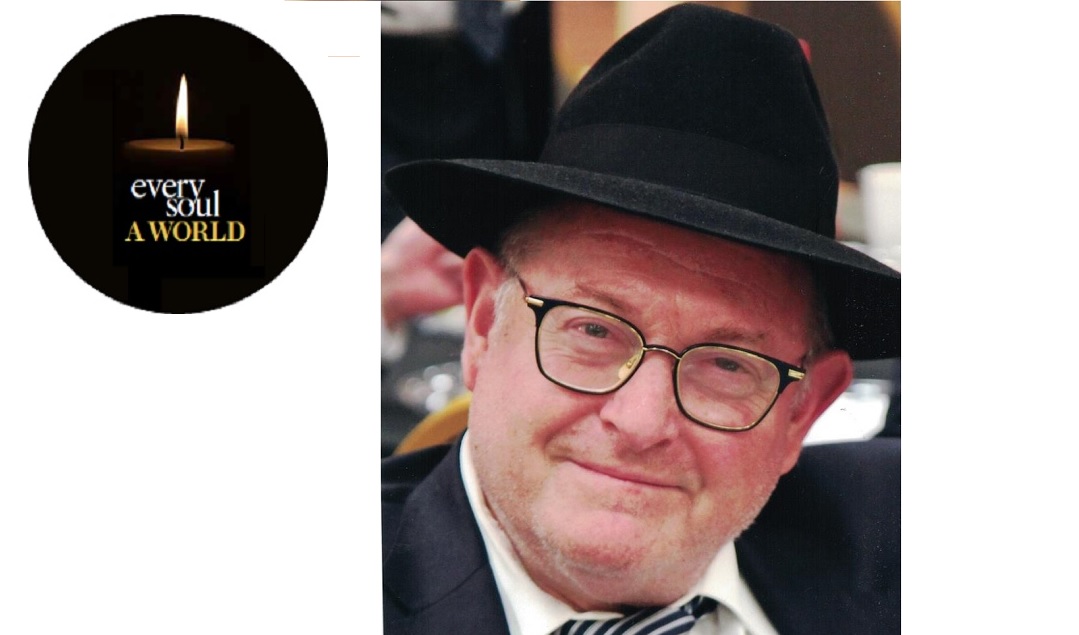

Dr. Arthur (Aharon Shaul) Turetsky

In tribute to Dr. Arthur (Aharon Shaul) Turetsky a”h

THE HEALER

E

very Friday morning, the daf yomi shiur at the Young Israel of New Rochelle would be given by Dr. Arthur Turetsky – and he didn’t stop smiling. His enthusiasm and excitement in giving over the daf was like that of a shanah alef kid who finally grasps the sweetness of the Gemara. He was a staple of the New Rochelle daf yomi chabura, but it wasn’t just the daf that excited this top-tier veteran pulmonologist – his personal Torah library could rival that of a small yeshivah, and he always made sure to get his hands on the latest sefer that had just been printed, stealing glances in his busy schedule bein gavra l’gavra.

But that wasn’t exactly the course planned out for him half a century ago, growing up in a traditional home in Bridgeport, Connecticut. Young, promising Arthur Turetsky was on a trajectory toward Ivy League university, medical school and joining his father's medical practice. While he did ultimately attend medical school and became a talented and successful physician, continuing in his father's footsteps, he took an unexpected detour along the way.

He had always been interested in his Jewish heritage even while attending public school, and upon graduation a young rabbi encouraged him to check out Yeshiva University. He was intrigued by the possibility of being able to learn Torah while getting a college degree – but when he broached the topic with his parents, they weren’t exactly enthusiastic. But Arthur wore them down with his assurances that he would continue on to medical school following his hoped-for yeshivah education. Family lore is that Rabbi Dr. Samuel Belkin, YU’s longtime, venerated president, called the Turetskys himself to make the case for a yeshivah education. In the end they acquiesced – but that meant Arthur would have a lot of catching up to do. So the summer before his freshman year, he taught himself Rashi script so that he wouldn’t be so far behind his fellow students.

He began his YU career in the JSS program geared toward baalei teshuvah and those with weaker backgrounds. By the end of his time in YU though, he had moved up to a regular yeshivah shiur – because once he started learning, he never stopped. His excitement for new sefarim and learning a new pshat never waned. There was nothing jaded or jaundiced about his view of Torah; it was all beautiful and exciting.

He kept his promise to his parents and attended Albert Einstein medical school where he met his wife Rochelle, also a medical student. After she finished med school and he completed his residency, they moved back to Bridgeport, where he joined his father's practice. Later, as their family grew, they moved to Fairfield, CT, where he took an active role in the local day school, ensuring the existence of Torah education for the very small Jewish community.

Dr. Turetsky worked at Bridgeport hospital for many years and maintained a nearby private practice, which enabled him to check up on his hospitalized patients.

Fairfield had no Jewish high school though, so in 1993, as the kids got older, they moved to New Rochelle, which was one of the closest frum communities to Connecticut. This way they could continue their practices there (Rochelle worked as a pediatrician and later as a sleep medicine specialist) while giving their children the opportunity to attend the large yeshiva day and high schools.

A Cup Overflowing

Some people need to be reminded of all the blessings in their lives. Dr Turetsky never took any of them for granted. His appreciation and respect for his wife was like that of a chassan in sheva brachos. Every morning as she woke up, she’d find a cup of coffee at her bedside, prepared just the way she liked. His pride in his three sons -- all committed to lives of Torah and mitzvos -- and grandchildren knew no bounds. A grandchild's sticky handprint that left its mark on his shirt would make him smile – it was just another reminder of the blessings in his life. With Dr. Turetsky, it was never a question of whether the glass was half empty or half full: It was always overflowing.

He didn't care about the latest styles and didn't get caught up in consumerism. If his shirt fit, even if it was twenty years old, it was good enough. Yet the one area where he appreciated the newest and best was seforim, and when it came to presents, his greatest joy was to buy seforim for his children. When he gifted a sefer, he would always write the date. His sons recounted that, looking a those dates, they realized that he had bought them various Rishonim and Acharonim on the Gemara when they were just nine years old, assuming that someday they'd appreciate it. And they did.

He was an early riser and would sit at the kitchen table every morning with his coffee and a sefer. His children say they don’t remember a time that they woke up and he wasn’t already there at his post, sitting and learning. His grandchildren visiting from Eretz Yisrael knew that when they would wake up at 4:30 a.m. from jetlag, Sabba would be sitting at the kitchen table, happy to pour them cereal.

He had a unique love of Eretz Yisrael. He and his wife visited often, especially after two sons and their families made aliyah. Toward the end of every trip he had a little ritual: He would go to the shuk and buy a kilo of rugelach, then carefully wrap them in his suitcase. Upon his return to New Rochelle, he would put the rugelach in the freezer, and every Shabbos morning he would have one rugeleh from Eretz Yisrael at kiddush. When his stock was running low, he knew it was time for a return trip. There was also no American-made grape juice to be found in the Turetsky pantry. All wine and grape juice in their house was made in Eretz Yisrael, mizimras ha’aretz.

The Rambam of Bridgeport

Dr. Turetsky’s schedule was intense (and he kept it up until he was hospitalized last month at the age of 71): Early morning wake-up, the daf before Shacharis, and then the drive into Connecticut, seeing patients in his office and checking up on those in the hospital. But despite the load on his shoulders, his very nature was laid back and relaxed. You could never tell if he was stressed or nervous, because his overarching goal was to make others – especially anxiety-ridden patients -- feel comfortable.

As a physician, he was absolutely committed to the health and safety of his patients. After his petirah, dozens of stories were posted online:

“Dr. Turetsky was the Perry Mason of his field, leaving no stone unturned in search of a diagnosis…”

“He was compassionate, friendly and funny. He was dedicated to his profession and exemplified a deep caring for his patients that went far beyond the call of duty…”

“The depth of my sadness at his loss is immense. He was caring and compassionate and I always felt that I could trust my care to him because he was careful and cautious and he always listened to his patients. He always ran late with his appointments because he was taking the time needed to spend with his patients and I knew that when it was my turn, he would spend that time with me also.

Medicine was not a job to Arthur. Medicine was a passion, part of his fabric. Healing was his life's calling, and his care and dedication made him one of the best doctors I have ever known…”

“I was always in awe of his immediate and proactive approach to treatment and diagnoses of not only my pulmonary issues, but also his recommendations for any other medical issues I might bring up. His care and concern not only for me as his patient but also for my family members as well, always struck a positive chord with me. He always had time for you along with that personal touch that is seldom experienced these days…”

“He was a colleague who I held in the highest regard for his knowledge, compassion and wit. Bumping into him during morning hospital rounds always left you feeling a little more hopeful for the coming day…”

“It is both unfortunate and ironic that Arthur delivered expert respiratory care with such intelligence and empathy to so many people that he had to die himself of a respiratory illness…”

“Arthur was among physicians of the highest regard and admiration. To me, he was the Rambam of Bridgeport…”

“Fifteen years ago I came from California to join the Bridgeport Hospital community and practiced in an office just above Arthur's. I quickly came to realize that not only was he an extraordinary physician but an amazingly kind and welcoming soul. I also realized he helped build the Bridgeport Hospital medical community, a kind of Camelot populated by committed physicians and staff who cared deeply about their community, their patients and each other…”

“Arthur was one of the rare doctors who still wanted a face-to-face consult with us radiologists. It was indicative of his kind nature, his congeniality, his wisdom, and most of all his concern for his patients…”

Neighbors and friends shared how at any hour he was willing to help them with their own medical situations, offer advice and give direction. His commitment to medicine was not relegated to his job or specific hours.

One might think, based on all this, that he was one of those “larger than life” personalities. But, say his children, he was the most quiet, unassuming man – even shy. Always sitting on the side at simchahs, taking pleasure in everyone else's joy. Never pushing himself to the front for any kind of attention or kavod.

Dr. Turetsky went into the hospital on Purim. As a pulmonologist and critical care doctor, he knew the signs. He told the medical team that he needed to be intubated immediately, and fought the virus that wreaked havoc on his body for five long weeks. Tehillim groups were set up -- hundreds of people said Tehillim around the clock in four full WhatsApp groups. The time between Purim and Pesach, from geulah to geulah, became a time of davening for a personal geulah and yeshua. His family joked that he would be so embarrassed and overwhelmed by all the people davening for him. "For me?" he would say. "Why did you make such a big deal?"

He left This World fifteen minutes after Havdalah of the second days of Pesach, leaving behind his grieving wife, sons, daughters-in-laws and grandchildren, plus a vacant spot in the daf yomi chabura of New Rochelle. When the world goes back to normal someday, Fridays in Young Israel of New Rochelle will never be the same.

Yehi zichro baruch.

VIEW/DOWNLOAD PDF FORMAT

I first met Arthur in 1966. We were freshmen with adjoining rooms in the dorm in YU. We spent 4 years together in a close knit group of premeds at YU and then spent the next 4 years together in medical school at Einstein.

We went through the major changes of life — from being teenagers to emerging as physicians being asked for advice — together. I have a picture of Arthur in my wedding album. We morphed from children to responsible adults together.

What I remember most about Arthur is that I can’t recall anyone not liking him. In the pressure packed, extremely competitive world of being pre-med during the height of the Vietnam draft, through the the daily pressures of medical school, when no one was likeable to everyone all the time, Arthur was the exception. Everyone liked him. I can’t recall him without his wry smile.

I last saw Arthur in Kennedy airport on the way to Israel. His son was my grandson’s rebbe. The years had not changed him. Conversations picked up as though we were still 17-year-olds in adjoining rooms.

Arthur kept the most important character trait that anyone could have - he was pleasant to everyone. I looked forward to any chance meeting.

I am a better person for having known Arthur. Why? Because Arthur remained, throughout life, a nice person, a mensch.

What I want Rochelle and the children to remember is that in my mind, the picture under the word mensch, is Arthur’s.

T’hei zichro baruch.

—Marc J. Sicklick, MD

Oops! We could not locate your form.