Rabbi Dr. Norman Lamm

| June 10, 2020

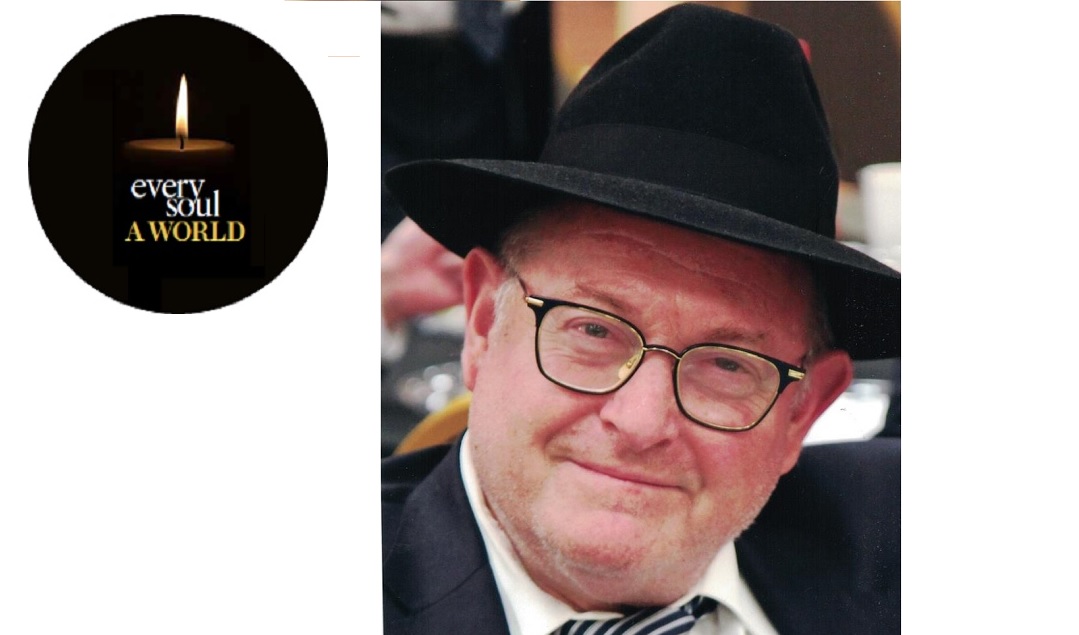

Rabbi Lamm (center) at the bar mitzvah of Rabbi Genack's son Moshe, 20 years ago

R

abbi Dr. Norman Lamm ztz”l (1927–2020), was a towering figure whose influence cast a lasting legacy, a sterling example, and timeless ideas throughout the Jewish community. He began his career as a pulpit rabbi, after Rabbi Samuel Belkin (then president of Yeshiva University and a student of the Chofetz Chaim), convinced him to leave a promising future as a scientist.

In 1976, Rabbi Dr. Lamm succeeded Rabbi Belkin as the president of Yeshiva University. As a fellow student of Rabbi Soloveitchik, I always marveled at Rabbi Lamm’s capacity to be both a talmid and a leader. In fact, his capacity to hold opposites, embrace dialectics, lead with sensitivity and poise, and champion Torah values in a changing world marked his entire life’s work and career. He received his formative Torah education at Torah Vodaath and developed his own leadership at the helm of Yeshiva University. He contained multitudes and endowed them all will dignity and royalty.

In 1997, just before President Clinton’s second inaugural, I was invited to speak beside him at the opening ceremony of the second inauguration. It was a moving gesture and a testament to my long-standing friendship with President Clinton. The only issue, however, was that it was being held in a church and I knew I could not attend. There are few people who can help navigate such a dilemma. But I knew one such person, Rabbi Dr. Norman Lamm ztz”l. My response required delicate language, passionate commitment, and a sensitive approach to an esteemed friendship. Rabbi Lamm possessed all of those qualities and this incident highlighted so much of what made him such an extraordinary man.

Rabbi Lamm helped masterfully affirm the centrality of religion in American life without veering into relativistic grounds of halakhic issues. This story demonstrates his ability to respond to dignitaries because Rabbi Lamm himself possessed such an aristocratic quality. Rabbi Lamm’s Haggadah, which the OU published, was in fact called The Royal Table. In his introduction, he explains the dual nature of the shulchan melachim, the royal table in Jewish thought. In one respect, “the phrase was used to express contempt for this crude class-consciousness.” As we find in geirus, a convert is rejected if they are motivated by sitting at the shulchan melachim — converting simply for the financial gains that affiliation may provide. Pirkei Avos reminds us not to aspire to a shulchan melachim, but rather to the table of scholars. We also find that shulchan melachim, certainly in the context of Shlomo Hamelech, is the gold standard of excellence.

This dialectic, Rabbi Lamm explains, must be our attitude toward royalty. And it was this duality that Rabbi Lamm embodied. He was at once self-effacing and uncomfortable with any sort of honorifics, while also imbued with a natural majesty that suffused his eloquent words and dignified manner.

Throughout his career, as pulpit rabbi, notably in The Jewish Center or later as president of Yeshiva University, Rabbi Lamm always had the right words to move communities. His words and drashot were timeless. His eloquence was able to capture fundamental truths that still resonate today.

There is another quality the incident with President Clinton highlights, though it is not explicit in the letter. Rabbi Lamm had a marvelous sense of humor. His first reaction, after I presented the dilemma to him, was to suggest, with a smile, that I figure out a way to check myself into a hospital. Afterward, he suggested, with another characteristic wink, that I append to the letter in a postscript that I have many colleagues who are not so principled who would be happy to join in my stead. His humor, like his scholarly ideas, was sharp and sophisticated. Never a gag, always a clever word.

Another of Rabbi Lamm’s qualities was the ability, and perhaps a striving, to bridge intellectual gaps and to encompass what seem to be irreconcilable opposites. His doctoral thesis on Rav Chaim Volozhin (the basis for his book, Torah Lishmah) is an in-depth study of what could be considered the quintessence of the misnaged approach to Yiddishkeit. One of Rabbi Lamm’s other major works, however, is The Religious Thought of Hasidism: Text and Commentary, winner of the 1999 National Jewish Book Award in Jewish Thought.

Rabbi Lamm’s writings also express how highly he valued secular knowledge, while at the same time he staunchly defended Orthodoxy and warned of the corrosive effects of contemporary culture. Rabbi Lamm wanted to embrace disparate counterpoints of knowledge, but always under the rubric of Torah. Rabbi Lamm was able to embrace opposing poles and had a magisterial quality to preside over a wide range of ideas that through his prose became his subjects, of sorts.

Finally, above all, Rabbi Lamm’s treasured our mesorah. In his introduction to the Haggadah, Rabbi Lamm recalls sitting at the Seder of his zaide, the famed author of Sheilos u’Teshuvos Emek Halachah. He vividly remembers how his grandfather would react when recounting the Jewish people’s servitude in Mitzrayim. “He was totally silent,” Rabbi Lamm writes, “as we continued to read aloud from the Haggadah. He said nothing, but tears streamed down his face and onto his beard. I do not recall if anyone else noticed, but I did.” Rabbi Lamm, reflecting on this memory, saw his grandfather relive the horrors and traumas he witnessed during the Holocaust. As he read the story of the Jewish people’s suffering, he wept for his own mother, his brother and his sisters all lost in the Holocaust. Mesorah, for Rabbi Lamm, was something deeply personal and, as he saw in his grandfather, it was the mechanism through which the past continued to reverberate in the present.

In 1958 he began the Torah journal Tradition and in his editor’s note in the inaugural issue he explains the title:

Tradition is perhaps one of the most misunderstood and maligned words in our contemporary vocabulary. It has been misconstrued by some as the very antithesis of “progress” and as a synonym for the tyranny that a rigid past blindly imposes upon the present. For others the word evokes different associations. Tradition becomes for them the object of sentimental adoration, the kind of nostalgic affection which renders it ineffective and inconsequential, like the love for an old naïve grandmother — possessing great charm, but exercising little power of influence

Rejecting both, Rabbi Lamm eloquently explains his approach to Tradition and our mesorah:

The focus of Tradition, is then, the future and not the past. “Tradition” is thus a commitment by the past to the future, the promise of roots, the precondition of a healthy continuity of that which is worthy of being preserved, the affirmation that the human predicament in general, and the Jewish situation in particular, are nor frighteningly new, but that they grow out of a soil, which we can know and analyze and to use to great benefit.

This is the mesorah that Rabbi Lamm so bravely protected when ensuring the financial health of Yeshiva University. This is the mesorah Rabbi Lamm so revered in his deference and esteem for his rebbe, Rabbi Soloveitchik ztz”l. This is the mesorah that motivated his life’s work of bringing Torah to thousands and his singular defense of mechitzahs in American synagogues as much of the country looked at such traditions as antiquated. And this is the mesorah he helped me convey in that letter to President Clinton. Royal words couched in a welcoming and warm tone.

Rabbi Lamm was truly an aristocrat of the Torah community. His absence makes us all a bit more plebian while his memory and example continues to ennoble.

Oops! We could not locate your form.