Checks and Balances

Photos: Menachem Kalish

They start off their marriage on the blessed island called kollel life, of living each day immersed in the spiritual energy of learning Torah, or of enabling a spouse to learn Torah.

Then it starts — a casual comment, a financial reckoning.

And when that moment comes — as it inevitably does for most — when the kollel years give way to a different reality, the battle begins.

It’s the battle not just for time and space, but for an identity, a battle that will never really end. How will the home react to the change? How will the next chapter unfold, once the shift is made?

Is it possible to keep a Torah focus if the father spends most of his day serving customers, balancing numbers, or developing properties?

This challenge forces couples to look inward and answer tough questions about themselves,

about their hopes and dreams and ambitions for the future.

Often, it will also send them to the homes or offices of their rebbeim or rabbanim — wise, experienced voices who can help map out the road ahead, point out both the pitfalls and the opportunities.

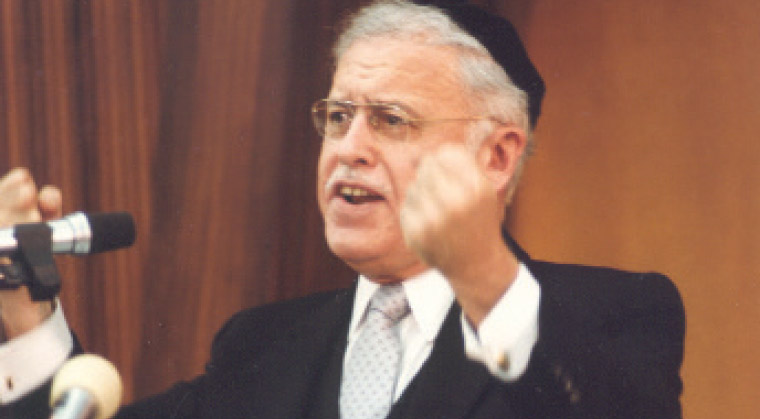

Rav Elya Brudny: It Was There All Along

Chazal will often point to a case of two people who appear to be similar and experience identical situations, yet their outcomes are very different

Chazal analyze and identify the pivotal element that creates that difference.

Today, we see two types of balabatim: the balabos who is fully engaged in making a living yet he remains a ben Torah, and the balabos who enters the workplace and completely leaves yeshivah behind.

What’s the difference?

People don’t just suddenly split into two camps the instant they enter the workforce. The differences must have been present before, even if they weren’t always apparent or evident. In the case of these two working men, both learned in yeshivah and kollel, but one was always deeply connected to the Torah with nothing else competing for his mind and heart. When this person leaves kollel because reality dictates that he feed his family, he signed a kesubah and undertook to support his wife, after all, he remains the same person. He is essentially connected to the Torah just as he always was, and the Torah itself is guiding him in this decision.

The second one, however, learned well, but he was always drawn in by the world beyond the beis medrash. He leaves kollel for the same reason, but he runs headfirst into the world that has been beckoning for so long.

The moment that the doors to the outside world open is the moment you see what was really going on all along.

It’s very sad to see people who really learned well, they toed the line, they appeared to shteig in yeshivah and kollel, suddenly become unrecognizable. Three months after they’ve gone to work, they look different. It’s very unsettling. What happened?

The factor that creates a Torahdig balabos lies in a single word: shei’fos. Spiritual goals. Dreams of growth. That’s it.

A person, a couple, with dreams of growth, are Torahdig. If they are aware of what they’re accomplishing and they live with spiritual reckoning, they will remain connected to Torah.

I recently heard something that moved me. A gentleman in Lakewood, a balabos, wanted to have a connection with Rav Shlomo Feivel Schustal. When Rav Shlomo Feivel moved to Lakewood, this man asked for a seder with the Rosh Yeshivah, who had a very full schedule. Where did they find the time to learn? He offered to drive Rav Shlomo Feivel to yeshivah each day. Once a day, during this five-minute drive, they learn mussar. They’ve almost completed the entire Shaarei Teshuvah. Because this man realized that Olam Hazeh is a tough place — it pulls you down and tries to break you — he found himself something to keep him inspired.

Baruch Hashem, we have choshuve, serious, talented rabbanim in most communities, people who can keep your vision intact, your hopes intact, and who can keep imbuing you with shei’fos. You can be the one to start the chaburah or shiur; you can incorporate the time into your weekly schedule. Asei lecha rav, v’histalek min hasafek. Make yourself a rav, and remove yourself from doubt. (Avos 1:16). Letting a rav into your life makes everything clearer.

Go over on a Motzaei Shabbos to talk with him, drive him places, go walking with him. Make it a priority. Go with your wife. Include her in the process. Learn a sefer with her as well.

Becoming a Zevulun is an avodah, not a vacation from avodah, and it takes work just like everything else in life.

And always, always keep the balance. Don’t go to sudden extremes. Be a wholesome person, a good husband, and a good father. Invest time and real attention to creating satisfying relationships with every member of your family, which will be a starting point for whatever goals you have in life.

Then, if you have true ahavas Torah, if your wife and children see how much it means to you, they will want to make it possible for you to learn. No one can leave kollel and evolve into a true Torahdig balabos if he’s not in partnership with his family.

Finally, let the Torah shine its light into every area of your life. There is no decision in life, no area, which isn’t rich in Torah; whatever questions you’re facing, expose your family, and yourself, to the depth of chochmas haTorah on that topic. If you want to institute a minhag or practice, learn through it with them, let them feel it the way you do. Show them that Torah isn’t just something we learn, but the way we live. Don’t live superficial lives, but lives in which Torah shows color and meaning to every detail.

If you’re committed to living within the parameters of His Will, you will find out how vast the Torah is, and how great you can become, whatever you are doing from nine to five.

Rav Elya Brudny is a rosh yeshivah in Mir-Brooklyn and a member of the Moetzes Gedolei Torah of Agudath Israel of America. The above is based on the Rosh Yeshivah’s words at the most recent Agudah Convention.

Rav Yisroel Reisman: Battle That Entropy

Often, when people ask for shidduch information about a yeshivah bochur, they ask whether he will be kovei’a itim, set aside time for learning, once he leaves yeshivah.

At that point, the answer is certainly that he will. After all, a person who is currently learning full-time undoubtedly appreciates the value of Torah study.

What happens later? What causes some young men to fall in this area?

Entropy is the natural tendency of things to slide into increased levels of disorder and chaos, unless great effort is expended to avoid this. Couple that with our tendency to focus on the new and most immediate challenges in life, and it grows clear why a young man who leaves yeshivah to enter the workforce focuses primarily on succeeding at his new occupation and doesn’t manage to set aside adequate time for learning.

In the yeshivah world, a “chassan shmuess” is considered an integral part of preparation for marriage. A similar shmuess is needed to prepare young men for their adjustment to the workforce. Will one shmuess, or even a series of shmuessen, really reverse a trend? Not on its own — but it will serve to redirect the person’s focus, creating awareness of a need for a spiritual focus during this transition.

Rav Yaakov Kamenetsky ztz”l would offer the following insight to his talmidim. When Yaakov Avinu set out to Lavan’s home, he detoured for a 14-year stint at Yeshivas Sheim v’Eiver. But he was 63 years old and had learned all his life in his father’s yeshivah. Why make the switch now?

Rav Yaakov answered that in Yeshivas Yitzchak, Yaakov Avinu learned the Torah of the home of the Avos. Now, he was setting out for Lavan’s home, a very different environment. Yeshivas Sheim v’Eiver prepared him for that setting.

Hearing this, I wondered: What do we know about the unique teaching of Yeshivas Sheim v’Eiver? Couldn’t we use some of that instruction today?

Chazal revealed to us only one unique aspect of Yeshivas Sheim v’Eiver. As Rashi tells us, for those 14 years, Yaakov did not sleep in a bed. He pushed himself to learn, even when tired.

What a preparation for going out to work! Yeshivas Sheim v’Eiver taught mesirus nefesh for learning. Learning when it is difficult.Is preparing for the workplace all about learning?

Of course not. Young men making this transition need to prepare for the new nisyonos they are bound to face, the challenges of a secular environment with different values than those of the yeshivah. What will they do the first time a coworker makes an off-color joke? What if it’s the boss? Laugh? Smile?

I know people who have earned the respect of their coworkers so that they no longer make these jokes in their presence. But it is difficult to get to that point. It takes unusual strength of character, and must always be accompanied by an admirable degree of interpersonal behavior. People who are happy and positive in their overall relationship with coworkers, who cover for others’ errors and speak well of them, can garner that kind of deference.

But the key to all that is, and always has been, kvias itim, Torah study. Those who stick to learning are best prepared to master the new challenges.

There are two important reasons for this. First, discipline and commitment to regular Torah study build strength of character. We see this everywhere, in bochurim, in kollel yungeleit, and certainly in bnei Torah joining the workforce.

More importantly, the self-image of a ben Torah heading to work is crucial to his success in avodas Hashem. In fact, in one of his letters, Rav Wolbe writes that a ben Torah going into the workplace should seek to maintain the same levush — style of dress — for precisely the reason that he will thus maintain the self-image of a ben Torah.

Beyond the clothing, however, the most important element in maintaining this self-image is the actual learning. If a working ben Torah’s learning falters, and he is unsuccessful in adhering to the kvias itim that he envisioned, he will develop a negative self-image. If he sees himself as having fallen, he may sense that he is no longer a ben Torah. It is a feeling that, chalilah, can feed on itself. This is why a late-night mishmar, Torah sedorim, Yarchei Kallah on secular holidays, and Shabbos sedorim are so important.

Chazal teach, “L’olam yilmad adam b’makom shelibo chafetz — a person should study that which his heart desires.” A person will succeed in his learning and will focus more effectively when he chooses an area of study for which he has an inborn drive.

These words obligate us. In preparing for kvias itim, search for a section of Torah that will resonate for you. Is it halachah l’maaseh, is it the lomdus of the yeshivah masechtos, or is it the drive to finish masechtos and acquire a breadth of Torah knowledge?

Figure it out. Speak to a rebbi who knows you and explore the possibilities. A person with drive is a person who succeeds. Create that drive.

Yes, it takes effort and preparation. But when you think about it, you’ll realize that anything meaningful takes drive and preparation. Otherwise it is all entropy.

And the key to battling that entropy is regular learning. Not just because of the learning itself, but because of the commitment to Torah that the learning represents.

Rav Yisroel Reisman is a rosh yeshivah at Yeshiva Torah Vodaath and the rav of Agudas Yisroel of Madison.

Rav Reuven Leuchter: Calculate the Cost

When a young man leaves the shelter of yeshivah for a job or business enterprise, he discovers two new worlds: one outside, and one within.

A yeshivah bochur today leads a life that is largely cut off from the outside world. When he enters the workforce, he not only discovers that there is a world out there, but also that it can be interesting, challenging, and full of opportunities. As he starts bringing in money and tapping talents and skills he barely knew he possessed, he finds this new world increasingly compelling. As his potential unfolds, and he discovers that he can be creative, enterprising, responsible, and all sorts of attributes that may not have found expression while he was in yeshivah, he begins to experience life in a new way. And he finds himself in need of new spiritual tools, as well.

Of course, the fact that the outside world is fraught with nisyonos different from the ones he faced in yeshivah isn’t exactly breaking news. Back during his yeshivah days he knew, in theory, about the broad range of possibilities out there, and he may already have grappled with their distracting allure. But there is an essential difference between dealing with these same nisyonos as a yeshivah bochur and dealing with them now, as a man who is out in the world.

You might compare it to the difference between the attraction wielded by worldly comforts to an average person versus a person of means. Both these people have the same desires, and those desires may get in the way of their avodas Hashem. But the average man can’t just reach out and procure whatever he wants from the world; his financial status is a firm impediment, a filter that blocks him from fulfilling every random whim or desire. This doesn’t mean he has no nisayon. The desire still exists. But for the most part, it remains in the realm of fantasy.

A man of means, on the other hand, can turn his wishes into reality with the swipe of a credit card. Desires flitting through his mind are not all he has to deal with; all sorts of comforts, luxuries, and opportunities are actually there, waiting to be transformed into reality at his beck and call.

Likewise, the transition from the yeshivah world to a secular field of endeavor brings a young man’s nisayon from the realm of imagination to the realm of solid reality — and it may catch him inadequately prepared. It follows, then, that if we want to equip our young men with coping tools for the nisyonos of the outside world, we need to habituate them to overcoming difficulties that are actual and not just theoretical.

We needn’t look too far to find places like that in a yeshivah bochur’s life. Yeshivah bochurim face real-life struggles in all areas of their sheltered existence. For one, the main struggle is in learning, for others, it might be in tefillah, complying with halachah, or in middos. The problem is that when we come up against a challenge like that, we tend to see it as an obstacle in our path, something that we have to push our way past or through. And we think that the way to do that is to ignore the challenge, close our eyes, bite our lips, and concentrate on doing what we’re supposed to do.

Chazal don’t think so. When they teach us how to find the right path for our personal avodah, they tell us to make a calculation: “Always calculate the cost of a mitzvah against its reward.” The “cost” of a mitzvah is the price I have to pay for it in terms of exertion, money, or any difficulty involved in fulfilling it. One bochur finds it hard to get up in time for davening, another finds no enjoyment in learning. Everyone encounters some sort of difficulty in his avodas Hashem. And all these things should be considered in our personal calculations.

We are generally in the habit of looking only at the sechar mitzvah, usually in terms of how much the mitzvah can elevate us, how worthwhile it is for us spiritually. But Chazal tell us that we should give equal consideration to the other side: What price must I pay to fulfill this mitzvah? What does it demand of me, and at what point do I feel myself resisting? What is it that I think I’m losing, as it were, by putting aside my own wishes and doing ratzon Hashem?

By answering these questions, we can learn a lot about ourselves and about our personal pathways to avodas Hashem. If we instead try to ignore the difficulty, grit our teeth, and push on, we miss our chance to discover new, unrecognized abilities within ourselves.

When we find that something is hard for us, we are standing at a crossroads. Listening to the voice inside that’s saying “This is hard,” instead of repressing it, can help us choose the best way to go forward.

To do this in a healthy way, we need to relate to the challenge like a doctor diagnosing an illness or performing an operation, cool and unafraid. Let the “patient” inside us talk about what’s bothering him, and let us listen with interest in order to decide on the right approach to treatment.

For example, let’s take a bochur in a yeshivah where the typical approach to learning is that the boys sit and prepare written summaries of the shiur they’ve heard as a form of review. While most of the bochurim manage fairly well with this method of learning, this particular boy feels something in him resisting it, and it seems to be growing worse every time he sits down to summarize. Learning is becoming a tiresome burden, and he is losing interest in it.

If this boy views his resistance to summarizing as a bother, and thinks the way forward involves gritting his teeth and ignoring his resistance, then he’s also subliminally viewing himself as a rebellious type who doesn’t want to sit and learn. Even if he succeeds in forcibly overcoming his inner resistance and doing what the yeshivah expects of him, he loses his chance to develop his learning ability in the best possible way.

If, on the other hand, he focuses on his resistance and relates to it in an analytical manner, he might find out many truly useful things about himself. He may come to realize that summarizing isn’t his strong point, and he may be prompted to find a method of review that better suits his personal abilities. This approach will actually build him up and allow him to discover heretofore unknown potential.

The same method can be utilized by each person who goes out into the world of secular endeavor. The difficulties we encounter in our avodah, whether in yeshivah or in the outside world, needn’t be treated as hurdles to power through or a sorry fate that we have to bear forever.

By realizing the potential inherent in our challenges, we can use them as guideposts on our personal path in the service of Hashem, as keen indicators of our unique internal makeup, and keys to personal growth.

Rav Reuven Leuchter, a primary disciple of Rav Shlomo Wolbe ztz”l, is among the leading mussar personalities in Eretz Yisrael today, with his worldwide network of shiurim and teleconferences. He is the author of Meshivas Nefesh on the Nefesh HaChaim, an annotated commentary on Rav Yisrael Salanter’s Ohr Yisrael, The Pesach Hagaddah, and the soon-to-be-released Living Our History.

Rav Yosef Elefant: Hold On to the Light

There are many mitzvos that we are obligated to perform constantly, but Torah is different: “When you sit in your house and when you walk on the road, when you lie down and when you rise…”

The phrase “Uvelechtecha vaderech” teaches that Torah must accompany you. What does this mean?

Yaakov Avinu received a unique brachah of “Ufaratzta yamah vakedma,” an assurance that he and his children would spread out across the world. That blessing taps something unique to Yaakov.

In parshas Vayetzei we read that Yaakov Avinu, the Father associated with Torah learning, comes to a place seemingly devoid of holiness and falls asleep. Upon arising, he exclaims, “Achen yesh Hashem bamakom hazeh, ve’anochi lo yadati — Indeed, Hashem is in this place, and I did not know.”

Yaakov Avinu was able to discern the latent kedushah in that bare hilltop, the potential for spiritual ascent that was there, just beneath the surface. This ability, this vision, says the Sfas Emes, was the factor that resulted in the brachah. For someone who can uncover holiness in a place where it’s hidden will carry blessing with him wherever he goes. That’s the “emes” of Yaakov Avinu, the ability to find the truth under layers of deceit, and the reason why he merited the “nachalah bli metzarim — the boundless inheritance” (which we refer to in Shabbos zemiros): The whole world is his.

The ohel, the tent associated with Yaakov, who’s described as the ish tam yoshev ohalim, hints at the nature of his gift, the Torah. Much like a tent, it is not outside the person, but within him, able to travel with him from place to place.

How does one make Torah a part of him so that it transcends geographical limitations and time constraints? How does one make it accessible when he is “on the road”? How does one uncover the emes, the truth that defines both Torah and Yaakov Avinu?

The secret to acquiring that sort of connection with Torah lies in one more feature of Yaakov Avinu’s life.

The Gemara tells us that Yaakov Avinu instituted tefillas Arvis. Yet in another place, we learn that the tefillos correspond to the daily korbanos; while Shacharis and Minchah represent actual korbanos, Maariv represents the burning of the leftover fats and limbs, which takes place throughout the night.

The Meshech Chochma explains the duality inherent in Maariv: It’s both the tefillah of Yaakov, and the parallel to the residual korbanos of the previous day. He points out that the nevuos perceived by Yaakov Avinu were given at night, because that was Hashem’s way of telling him that even though night was about to fall — he was about to descend into galus — he would still be able to experience that connection with Hakadosh Boruch Hu.

Because he’d already formed that connection earlier, before the descent into galus.

A relationship cannot be created in darkness, but once it’s created in a time of clarity, it can then continue even within the darkness.

Yaakov Avinu established tefillas Maariv, the prayer of the nighttime — of galus, and the burning of the leftover parts of the korbanos. Those leftovers are remainders of the holiness, a continuation of a connection formed during the time of light.

The same principle is the key to Torah’s ability to spread. It can accompany its master throughout a long, dark night — but only if it comes from a sacrifice made during the day.

And this is the answer to the questions of hundreds of pure, sincere young couples looking for a way to hold onto that which they experienced during their years in kollel, yeshivah, and Bais Yaakov.

Find the light. The connection must be formed at a time when the doors are open.

And then you will have a wellspring from which to draw.

And even after those years are over, we still have times of light within the darkness. Make them count!

When in kollel, a young man learns on Sunday just as he does every day. Now imagine he’s left kollel, he’s become an accountant or property manager or electrician. That’s from Monday to Friday.Why has Sunday changed?

Of course, any talmid who’s learned seriously in yeshivah knows about balance, about the realities within each home, and the responsibility to meet the needs of his wife and children. Of course she has a real claim to his time.

Sunday is just the mashal, the first battleground they can eye together, a means of opening a door to light that will help illuminate the week ahead. If he can learn an intense, serious, yeshivah-style seder on Sunday, his week will look different, and then he will look different. His home will benefit, his wife will benefit, his children will benefit.

Not every working ben Torah will walk down the street thinking in learning, but at the very least, he should have what to think about in learning.

The connection has to be vibrant, and then, when there are challenges, that early foundation of Torah becomes a reservoir supplying him with clear water. That’s what it means that Torah accompanies you “velechtecha vaderech.”

That’s the mandate to learn Torah constantly: It can and should be a steady companion, whatever your situation is. Use Shabbos and Motzaei Shabbos, Sundays, and vacation days correctly, and the effect will spill over into every area of your life. When you learn Torah with focus and responsibility, you are uplifted, you will form a deeper connection with the Borei Olam.

A mature person knows how to plan a Sunday without depriving his family of their rights to his time. Seize the times of kodesh and then your chulin will be holy as well.

Then you can bring kedushah to every place, like Yaakov Avinu, the father who forged the path of finding light within darkness, of remaining connected within galus.

The ones determined to make the most of each moment find that when they cannot learn — when they are overwhelmed at the office, when it’s tax season or trade show season — they can still dig deeper and find holiness.

The Torah they have made a part of them, that they still make a part of them when the opportunity arises, is there for them. It gives them a place to escape to that’s a bit higher than their surroundings, the strength to fight the allure of the contemporary street, the pride and confidence to stand tall.

How fitting that the place of which Yaakov Avinu said “ve’anochi lo yadati” ultimately became the site of Hakadosh Boruch Hu’s dirah betachtonim, a level of hashraas haShechinah the world had never known before or since.

The transition to work only looks like it’s devoid of kedushah. To one willing to toil, to dig deep, it can be a place where he discovers that “yesh Hashem bamakom hazeh!”

Rav Yosef Elefant is a maggid shiur at Yeshivas Mir Yerushalayim. This piece, based on an address at the recent Agudah convention, was prepared for print by Yisroel Besser

Rav Eliezer Herzka: Living as a Ben Aliyah

Much has been said about the important topic of how to remain a ben Torah in the working world.

The nisyonos one faces on a daily basis — the constant assaults on kedushah and taharah, and the ever-present challenges to emunah — are truly difficult to overcome. Perhaps it is worthwhile to address this by focusing on a related issue: How to remain a ben aliyah in the working world. Presumably, in order to remain a ben Torah one must be a ben aliyah, so let us explore an aspect of “aliyah.”

Chazal tell us that Rabi Shimon bar Yochai said: “I have seen bnei aliyah and they are few. If there are a thousand, my son and I are among them; if there are a hundred, my son and I are among them; and if there are only two, my son and I are they” (Succah 45b).

If Rabi Shimon saw the bnei aliyah, why didn’t he know how many there are?

What, in fact, is a “ben aliyah”? In the Mishnah, the term aliyah refers to an upper floor of a house. Based on this, the Slonimer Rebbe shlita explains that there are two approaches to living in This World: A person can dwell “on the ground floor,” meaning that he is immersed in This World with all its materialism, or he can dwell “upstairs,” meaning that he lives in an elevated state, connected to ruchniyus. A ben aliyah is someone who inhabits the upper floor; he resides “in the aliyah.” This person may traverse the byways of This World and even enjoy some of its pleasures, but his focus is on the aspects of ruchniyus that abound — and, more importantly, his goals are spiritual.

This is one of the inherent differences between Yaakov and Eisav. When Eisav requested a brachah from his father, Yitzchak said, “Mishmanei haaretz yihyeh moshavecha — May your dwelling be among the fat of the earth.” This seems like a curious blessing. Why didn’t Yitzchak tell him, as he told Yaakov, “May Hashem give you of the fat of the earth”? What is the value of dwelling among the fat of the earth? Evidently, Yitzchak was addressing Eisav’s inner desire, which was not to enjoy Hashem’s bounty, but to be immersed in This World — to dwell in materialism and hedonism. Yaakov, on the other hand, takes from This World what Hashem gives him, what he receives as a result of “Veyitein lecha haElokim.” And therefore, everything Yaakov possesses has a spiritual dimension.

This distinction came into sharp focus on a trip to Eretz Yisrael shortly after my eldest daughter’s wedding. Unable to sleep on the flight, I made my way to the galley, where I met another insomniac. This highly intelligent gentleman, a CIA agent traveling on a classified mission, had recently attended a Jewish wedding and was curious about my role as father of the bride. When he learned that I had paid the catering bill, he was astonished: “If your daughter wanted to get married, why would you pay for her wedding?” His question highlighted a gaping chasm between the basic values of a Yid and those of secular society. Would any erliche Yid forgo the privilege of marrying off his daughter? Our children are our future, and marrying off a child is the height of our ruchniyus and gashmiyus combined! But what we view as our greatest zechus is something that others can’t begin to understand. And I’m not referring to a lofty madreigah, but to something that is instinctive to every frum Jew. Our most basic instincts are on a completely different plane than the values of even an educated, intelligent secular individual.

We all live “upstairs,” though we may not always realize it. Society around us is mired in the quicksand of Olam Hazeh, in which even something as meaningful as a child’s wedding is just another opportunity for drinking — on the child’s tab. The surrounding society can’t even fathom the myriad forms of chesed that we take for granted and perform almost automatically. For lack of any meaningful ideal, they engage in shallow pursuits. It behooves us to recognize that our dwelling is high above theirs, that our standards are so much more refined, and that their pursuits are utterly incompatible with our instinctive values.

This type of aliyah is not limited to a single upper level; there are numerous ascending levels, and the more one strives for ruchniyus and uses gashmiyus in a way that imbues it with spiritual value, the higher the floor on which he lives. This is what Rabi Shimon bar Yochai meant. There are not many bnei aliyah, and the number diminishes as one reaches increasingly higher stories. One flight up, there are perhaps a hundred; twenty flights up, there are perhaps ten; and a hundred flights up, there are perhaps only two. But Rabi Shimon bar Yochai and his son Rav Elazar, who spent 13 years in a cave living on carob, were surely among the bnei aliyah whose existence was more spiritual than material.

As a child, I once visited Manhattan. Traveling the streets, I was amazed by the glitz — the fancy stores, the elegant clothes, the shiny cars. But then we entered the Empire State Building and ascended to the observation deck on the 102nd floor. Looking down from that level, the stores did not seem as fancy, the clothes did not seem as elegant, and the cars did not seem as shiny. At that higher vantage point, all the glamour disappeared.

If we can succeed in tapping into our genuinely Jewish values, our powerful innate connection to ruchniyus, our instinctive drive for chesed, and all our other inherent strengths, we will automatically find ourselves living on an upper story of This World. From there, the allure of Olam Hazeh will evaporate, and the temptations of the working world will cease to challenge us. We will truly be bnei aliyah, not living in the working world, but traveling through it while living above it.

Rav Eliezer Herzka is the rav of Khal Meor Chaim in Lakewood. This article is based on his remarks delivered at the recent Agudah Convention.

Rav Moshe Hauer: Life Is Just Beginning

Klal Yisrael is blessed with hundreds of yeshivah graduates who fill the ranks of its shuls and communities. These men are learned and committed bnei Torah who are taking their places in the professional and commercial worlds. Their numbers could not have been anticipated even a generation ago, and they represent an outstanding resource for Torah and kiddush Hashem.

What are the typical characteristics of the successful working ben Torah who continues to thrive years after leaving the walls of the yeshivah?

1. Spiritually Ambitious

Given the high-cost of frum Jewish life, one cannot readily meet a family’s needs by simply “punching the clock” at work. One must be ambitious and creative, expanding reach and capacity so as to fund inevitably growing budgets.

This same sense of ambition should be brought to avodas Hashem. What makes for sustained success as a ben Torah is a refusal to simply “punch the clock” Jewishly by making it to minyan and a shiur or learning seder, and giving tzedakah. Ambition in Torah study includes exploring new areas of Torah, sharing Torah orally or in writing, and/or achieving mastery through formal testing programs, such as Dirshu. The ambitious Jew brings tefillah to life by an active effort to constantly infuse fresh meaning into his davening. And the engaged community member is driven to find new and meaningful ways to make a real difference in his community and in the lives of its members.

2. Well-adjusted and Self-aware

In every educational framework, all students start out together sharing a core curriculum. As they move along, the greatest success is achieved by those who differentiate, not in a radical sense, but by identifying and pursuing their unique skills and interests, creating for themselves a fitting and meaningful role.

The successful ben Torah will consciously and confidently adjust to the reality that upon leaving the broad highway of the yeshivah, he must find the particular path that will constitute his unique avodas Hashem. Rather than yearn for the good old yeshivah days, he will see his life as a ben Torah opening up ahead of him. In that light, he will be sure to identify “chelkeinu b’Torasecha,” the area of Torah that his heart is drawn to study, as well as the area of service that fits his unique skills and interests. He will understand that at this new stage of his life he must adopt the mantra of Rav Chaim of Volozhin: “This is what man is all about; he was not created for himself, but rather to help others in whatever way he can.” This will guide him to clearly define and identify with his role within his family and community.

3. Part of a Chaburah

One of the most motivating aspects of life in the yeshivah is the sense of belonging to a group of people and an environment dedicated to the service of Hashem. The value of that group identity is inestimable, and it is perhaps one of the biggest losses experienced when leaving the yeshivah. But it does not need to be lost.

Rather than focusing on how often he can visit his old yeshivah, the successful working ben Torah will be determined to find or to form a new group that shares his values and spiritual ambitions. Ideally, his group will have a rav or mentor with whom they will get together regularly to discuss the new challenges and opportunities of their current stage of life.

The successful working ben Torah understands that indeed life is just beginning. He is ambitious about his avodas Hashem in the years ahead. He is well-adjusted to his new reality, and ready to embrace the opportunities of this next stage. And he is committed to travel the road ahead with the company and encouragement of others who share his dreams. Together, b’ezras Hashem, they will accomplish great things for HaKadosh Baruch Hu, for Torah, for their families, and for Klal Yisrael. —

Rav Moshe Hauer is the rav of Bnai Jacob Shaarei Zion in Baltimore.

Rav Avrohom Neuberger: A Two-Way Street

Every educational system has its paradigm of success — an ideal prototype it aims to produce. A chassidish educational system tries to produce the perfect chassid; a Brisker educational system, a perfect Brisker; and a Bais Yaakov, the perfect Bais Yaakov girl. There is no need to describe the details of these profiles. Anyone exposed to each system intuitively knows the respective character traits.

And any educational system measures its success by how close the actual, flesh-and-blood products — i.e. the students emerging from the system — conform to the paradigm. The closer a given student is to the system’s ideal, the greater he or she will feel like a success. As such, a chassidish yungerman who may not excel in chassidic values but does excel in lomdus may not feel like a success, and similarly, a yeshivah man who has a pull toward chassidus but is not a classic lamdan may not feel like a success in his system.

The disillusionment felt by many balabatim results from the fact that the current educational system promotes only one image of success and does not give sufficient credence to an alternative image.

In post-World War II America, there were essentially two schools of thought regarding chinuch for the non-chassidic, chareidi world. One advocated Torah only, seeking to rebuild Torah after the decimation of the Holocaust; the other offered a more holistic approach, stressing other aspects of avodah as well, with the understanding that the young men would soon go to work. Hashgachah determined that the former should become the dominant voice, and this approach has experienced unparalleled success. But the collateral effect is a binary, polarized society: Either you are a “yeshivahman” or a “balabos,” and if you are the latter, you may feel like a failure of your educational system.

Yet the entire “us” versus “them” — “kollel yungerman” or “balabos” — is an artificial construct. In fact, there is a continuum between someone who is zocheh to learn full-time and one who has less time to be in the beis medrash. When someone goes to work, he did not “become” anything. He does not cross into an alternate universe inhabited by “balabatim.” There is no reason for him to shed his white shirt and go for the colored, or the polo shirt, or lose his hat in the transition. He is still part of his old team, so there is no reason for a new uniform. He is exactly who he was before; he just has less time.

But for him to maintain such a self-image, to still feel part of the system, then those still in the system, those part of the “team,” must embrace him as one of their own. It’s a two-way street. They have to view him as a success, and not a failure, and certainly not as a second-class citizen.

Perhaps then, some of the alternative vision must be incorporated into the chinuch message: that there is kedushah everywhere — for as Chovos Halevavos and Ramchal write, if Hashem places one in a situation where he has to work with “sibos” (mediums) to earn a learning, then those “sibos” themselves become a source of kedushah, and that “echad hamarbeh, v’echad hamamit” is recognized as fact. The many ways that a baal habayis can make his life meaningful can be incorporated into the educational model throughout the educational process.

If all throughout the process, an ehrlicher balabos is being held up as a paradigm of success as well, then one who goes to work will feel like an exemplar of the system’s success and also as part of the team. And that association itself is likely to generate growth in ruchniyus.

I have a dear friend, Moshe F., who arrives at shul at 5:00 a.m. and has a seder in Bavli, Yerushalmi, Mishnayos, and mussar each morning. He told me that as a bochur he had been tested for semichah and approached Rav Gedalia Schorr ztz”l to sign the semichah document. Rav Schorr responded:

“Your father is an architect and you are becoming an engineer. I will sign your semichah only on condition that you learn hilchos mikvaos.”

Rav Schorr was niftar that same day. Moshe then approached Rav Pam ztz”l, who said that he must fulfill that condition. Moshe did so over the next six months, and Rav Pam then gave him an hour-and-a-half farher on hilchos mikvaos.

That is the type of chinuch that teaches — and validates — a young man who is going into the workforce, and that produces a “balabos” who finishes Bavli and Yerushalmi.

One last thing: Perhaps we should replace the term “balabos” with “working ben Torah.” It may make all the difference. Chazak v’amatz.

Rav Avrohom Neuberger is the rav of Congregation Shaarei Tefillah of New Hempstead and the author of Positive Vision, a Chofetz Chaim Heritage Foundation project (ArtScroll\Mesorah).

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 750)

Oops! We could not locate your form.