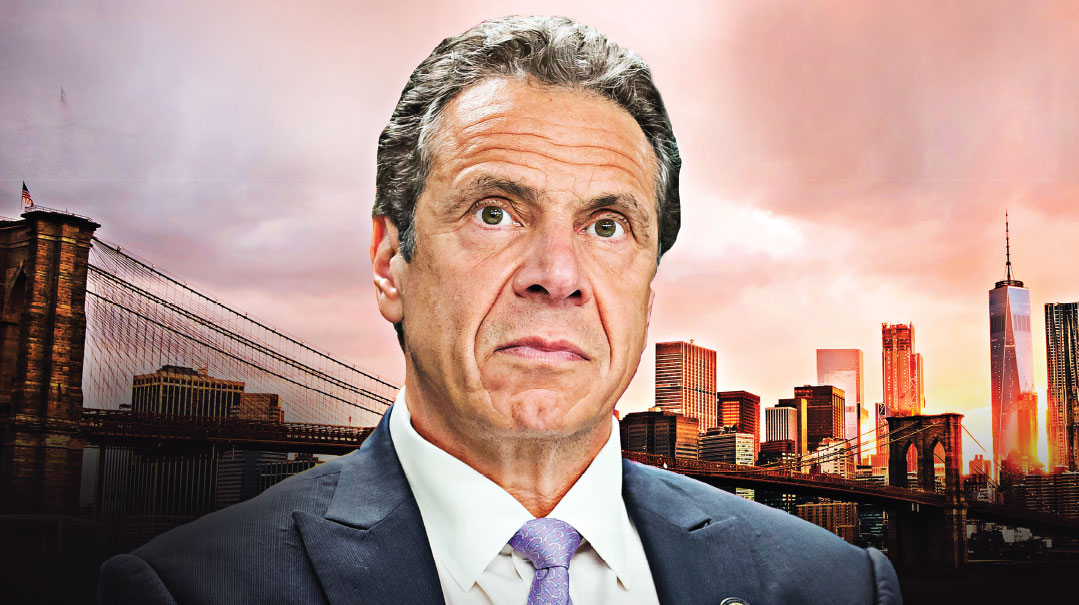

A Call to Arms

They sit among you, armed, trained, and ready should an attacker burst through the doors. They are shul marshals, the first of a new breed of security personnel. After Pittsburgh and Poway, no precaution is too extreme

Photos: Jeff Zorabedian

T

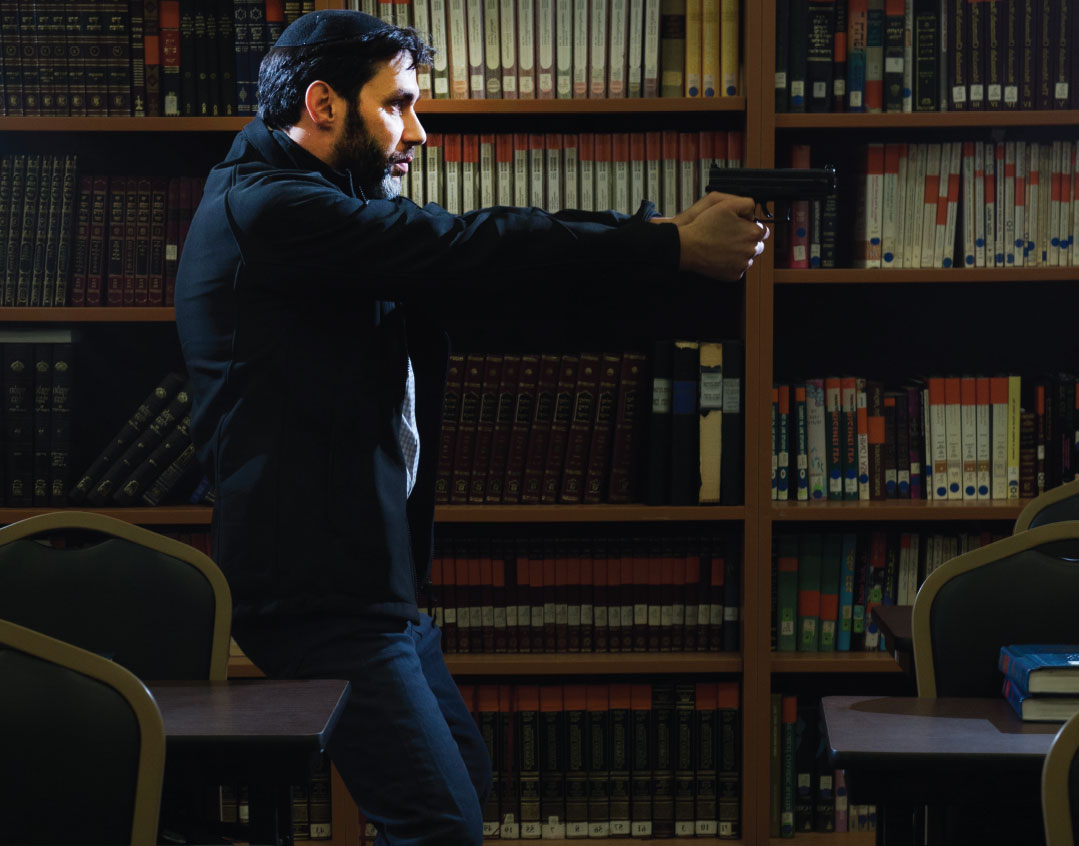

he six men stood suddenly, their profiles silhouetted against a row of targets taped to the wall.

“One,” barks the instructor.

The men jump toward the target, their hands raised in a defensive posture.

“Two,” comes the call.

The sextet yanks out handguns from their holsters in a microsecond, pointing their weapons toward the mustachioed man staring passively at them from the wall. “Threat! Threat!” they shout.

Then comes the final act in the one-two-three punch: “Three!”

And with that, the sound of six guns firing fills a cavernous hall near Monsey on a recent weekday evening. “Threat down! Threat down!” the men yell. The target is dead and the threat eliminated.

The scene unfolding in a giant educational complex could not have been more surreal. The room where the six men fired their weapons looks more like a student lounge than a shul where a terrorist has suddenly opened fire. Hebrew dictionaries peek out from beneath a shelf full of copies of Alice in Wonderland, all stacked neatly against a wall.

The men are part of the select Chevra L’Bitachon of Rockland County, a group of dedicated community members who have been trained in firearms and security by a former Israeli commando. They have one goal in mind: to keep shuls, yeshivos, and community institutions in the New York City-area safe.

Over the last five years, about 50 trainees have passed through the Chevra L’Bitachon program, which involves at least 200 hours of instruction and refresher courses once per month. Its members are spread out in more than two dozen shuls in Rockland County. Now, for the first time, the founders are revealing their work in the hopes of expanding into new shuls and creating an awareness of security threats. Their ultimate goal is to bring the program to the entire New York area.

“I’m a very big supporter of being proactive versus reactive,” says Mordy Eisenberg, one of Chevra’s founders. “Despite the preventive work that law enforcement does, unfortunately, once an attack begins, you have to have someone already on site during those crucial first minutes.”

Chevra was formed in the aftermath of the 2014 Har Nof terror attack that ultimately left five mispallelim dead. Eisenberg, a chief operating officer of a medical services company, woke up the morning following the attack with a dreadful feeling. If a mass attack could happen in Har Nof, in well-protected Jerusalem, it could happen in Monsey too.

He consulted with two friends, Ari Susskind and Hillel Kurzmann, and decided to get to work. The trio came up with the idea to model training on the federal air marshal program, which places armed guards dressed in civilian clothes on airplanes to protect fellow passengers in case of a violent or terrorist attack.

“Take any airline, any flight — it may have an air marshal, it may not have a marshal, you may know who he is, you’re not sure, but the guy might be on the plane, right?” Mordy says.

“Take a bunch of mispallelim and, without having to ratchet up security to the moon, have them do the same thing.”

“The goal is to utilize people from within the shul who are in a unique position to recognize who belongs there and who doesn’t,” adds Hillel. In Israel, he comments, authorities set up concentric rings of security to identify and deter terrorists. “If, chas v’shalom, someone gets inside with a weapon, there has already been a catastrophic failure,” he notes. But in the United States, most communal institutions don’t have the budget to implement that level of security. “So we approached this challenge differently,” he says.

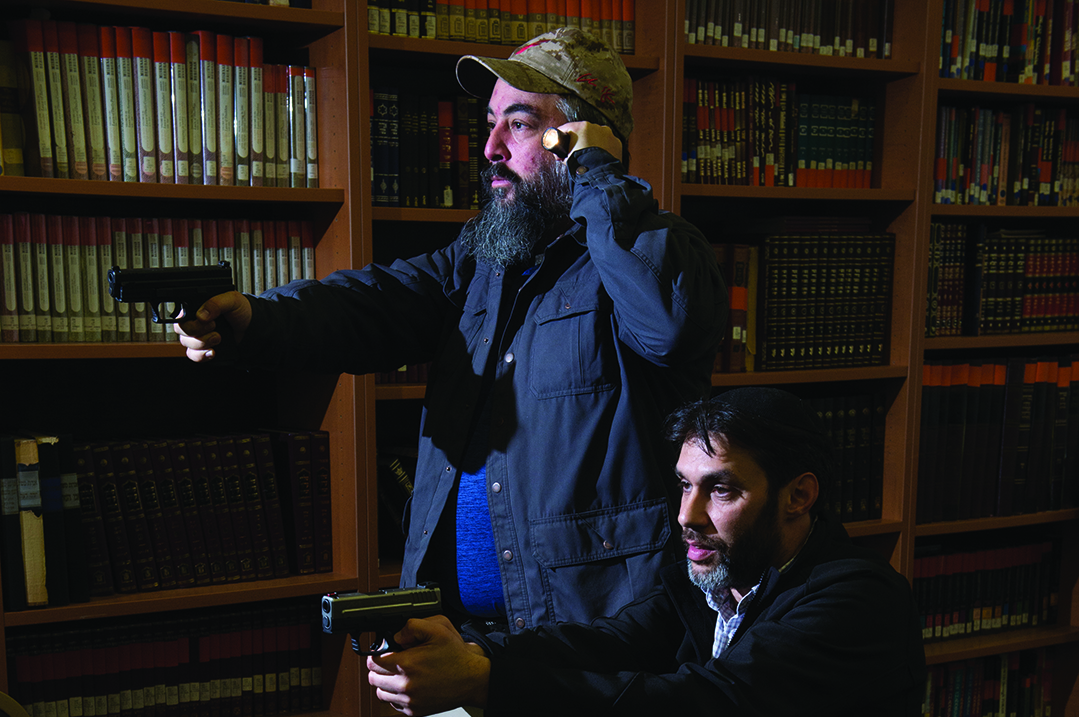

According to Albert Timen, a former Israeli counterterrorism expert who trains the Chevra volunteers, these security personnel should never be seen or heard. “When things happen, we just have to respond,” he says. “But nobody around you should know who you are or how you operate.” The first time, they act, he says, these men will surprise their friends and neighbors with their skills and abilities.

Timen, a slight, balding man with a salt-and-pepper beard, has trained police forces around the world in the science of confronting a mass shooter. He drills into his mentees the necessity of constant practice. There should be no hesitation if and when the time to act comes. It should be “like their bar mitzvah parshah,” he says. “A one-man SWAT team.”

“There’s never a 100,” Timen says. “They always have to work more and more repetitiously. The more they do the same thing over and over again the better they become, the faster and more aggressive their mindset needs to be.”

Timen prefers not to talk about his past work in Israel, but one Chevra member tells me he once worked undercover as an agent in Gaza. He received a top military award for stopping and arresting a suicide bomber strapped with explosives on his way to a target, one of his men say.

A resident of the United States for two decades, Timen is the founder and president of Kapap Academy, a security company that provides personal and tactical training to individuals and institutions. Despite his accomplishments, Timen prefers to remain under the radar. So too, the organizers requested that details of the training session I witnessed should go unreported.

W

hile Mordy and his friends thought they had a good idea, they realized that before proceeding they needed rabbinic guidance. Is it okay, both halachicly and hashkafically, to plant a civilian with a gun in a synagogue?

They went to consult with the late Rav Mordechai Berg ztz”l, who asked his rebbi, one of Monsey’s most respected rabbanim, to decide on the matter.

“The question that was posed to him was, is this the proper hishtadlus for a community to do?” Mordy recalled. “He asked for a few days to think about it and then he came back and asked for a few conditions, one of them being that we had to be very discreet about it. We didn’t just keep that as a condition that he forced upon us; that was our intention all along. He said that yes, this was the proper hishtadlus for a community to do.”

Today, the Chevra takes halachic guidance from Rabbi Ari Senter, the kashrus administrator at the Kof-K, and other prominent Monsey rabbanim, though they urge every community to seek guidance from their own rav. Mordy and his partners contacted Timen, who was enthusiastic about the proposal and helped them rapidly recruit the first group of trainees.

The Chevra does not advertise, preferring to work under the radar. It has no online presence, yet calls came “pouring in,” Mordy says, once they launched.

The training is rigorous, beginning with selecting the candidates for the job by consulting the rav of the shul. The Chevra rejects candidates who “hang around the kiddush club” or are not seen by congregants as responsible.

“We start with, first of all, identifying candidates we can work with,” says Ari, the group’s director of operations and training. “You want people who are mature, responsible, mentally well-balanced, and stable. There’s also a lot of hours to commit to,” so they ask members to dedicate themselves from the beginning.

“Our number one priority,” he adds, “is ensuring that our members are an asset to the community, never a liability.”

Once men are selected, Timen enters the picture. While some of the recruits are gun enthusiasts, many have never before fired a gun. Timen uses a plethora of industry lingo to describe what his goals are. “Attack the attacker.” “From flash to bang.” “Break his OODA Loop.”

The difference between a bloodbath and a successfully diffused situation, Timen says, is to break the attacker’s “OODA Loop,” which stands for “observe, orient, decide, act.” It refers to the series of brainwaves that rush through a person’s head when confronted with an unplanned event. All in less than a second, according to Brett and Kate McKay, who are renowned experts in matters of security.

“Most violent gunmen,” the McKays write, “work under the assumption that because they have a gun, people will do what they want or just hide. They don’t expect someone to come charging after them.…. An important part of winning any fight is resetting or disrupting your opponent’s loop. [According to] former US Air Marshal Curtis Sprague… you want your opponent to have an ‘uhhhh…’ moment. By doing the unexpected (attacking), Sprague argues that ‘you’re disrupting the gunman’s OODA Loop which slows him down — even if it’s just a few seconds — and gives you more time to complete your OODA Loop and win the battle.’ ”

For the Chevra volunteers that means their first reaction should be to observe what is happening, orient themselves to the situation, decide on a plan of action, and then act.

Mass shooters tend to arrive suddenly and, because they’re armed, remain in control of the situation, at least for the first few minutes. “We have enormous respect for law enforcement and we have a growing relationship with our local police departments,” Hillel observes. “However, they will be the first to tell you that we’re on our own for the first few minutes if there is chas v’shalom an attack. Our mission is to be there during those first few minutes to end the threat.”

In the New Zealand mosque shooting in March, for example, in which 51 people were killed, the attacker easily penetrated the building and shot at will without being confronted. “The guy is driving his car, with his camera on his helmet,” Mordy says. “He finally gets to the mosque where he’s going to do his attack. He gets out of the car and walks up to the front door. And you see him walking up to this mosque. And I’m thinking to myself when I watched this, This is every shul in town. Just walk right in.”

Timen says the Poway shooting is an example of how to break an attacker’s OODA Loop. The assailant’s gun jammed, disrupting his plan. At that point, he was rushed by a congregant and forced to flee. The same would have happened if he would have been jumped or confronted.

In addition to teaching Chevra members to shoot, Timen instructs them on how to evaluate a building from the outside. As part of the workshop, each inductee must visit a shul outside his neighborhood and provide a report on the building’s vulnerabilities. (In one such evaluation, a yeshivah was informed that its all-glass fa?ade was a significant security risk. The yeshivah administrators did not have money to build barriers, so they brought in a security expert who suggested they have rebbeim park their cars on the sidewalk directly in front of the entrance.)

The men know that they will likely never be recognized for the job they do. In fact, they are asked not to reveal their roles to shul members. It’s for their own safety, Mordy says. “Keep your mouth shut and don’t tell anybody that you have a gun concealed on yourself,” he tells the volunteers.

One member, a tall man with a Sefirah beard, speaks on condition of anonymity. He davens in a shul in Wesley Hills with about 300 members and became a member of the group about three years ago. An electrician by trade, mostly he just keeps his eyes and ears open, making sure his gun is always in his holster and it’s concealed under his clothes.

“It’s about coming earlier,” he says, “checking out the shul, making sure there’s nothing out of place, making sure there are no doors unlocked that should be locked, no packages that were not there the day before, and checking the cars outside — is there a suspicious van parked outside? Are there electric boxes open, did someone play with the gas box?”

So far, his tenure as a Chevra volunteer has been uneventful. His most heart-stopping moment came one Shabbos morning when a van drove up to shul and a man began walking toward him. But it turned out to be a false alarm.

“But a guy like me, because of the role that I took in the shul, I always have to be aware of what’s going on,” says the Wesley Hills man. “Obviously I’m here to daven. But I’m also here to make sure that everyone comes here to daven safely and gets home safely. That’s the way I look at my role. We have a gabbai, we have a rav, we have gvirim — my job is to make sure that everyone leaves the way they came.”

Another shul marshal, who asked to remain anonymous, says using a firearm is a last resort. “It’s about being proactive, being aware of your surroundings. Everything could be nothing and nothing could be everything,” he says.

T

hough there have been mass killings at churches in the United States, a shooting at a shul was rare. Then came the attack in October 2018 at the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh, in which 11 people were killed. That was followed by the attack at the Poway Chabad at the end of April, in which one congregant was murdered. “It made my stomach turn,” Mordy says. “And I hate to say this, but it made me feel a little bit vindicated that what we’re doing is the right thing.”

After those events, Mordy frets, some shuls have turned to unconventional methods to protect their houses of worship. One shul allowed a mispallel to walk around armed with an AR-15, and another inquired about purchasing an armory of shotguns and training mispallelim to use them. Another shul has armed mispallelim but requires them to keep their weapons locked in a shul locker and not wear them outside of the tefillos.

“What we’re finding now, is that you have people coming out of the woodwork and looking for guidance,” Mordy says. “They’re reaching out to dubious people. What we realized is, somebody needs to step forward and be a resource where people can ask questions if they want to do it right.”

Toward the end of the session, Timen takes the group on a final reenactment of a shooter in a school. Four targets are hung up for this practice, and each member must neutralize the attacker while remaining safe himself.

“On the one hand, our format is very demanding,” Albert says. “But on the other it is rewarding because you know that when a guy like that is in shul and he knows what he’s doing, you’re much safer as a community.”

Carrying a Gun to Shul?

Some of The Halachic issues that arise with regard to carrying weapons for shul security:

- Are weapons allowed in shul altogether?

- Is a gun muktzeh?

- May one carry a gun outside on Shabbos where there is no eiruv?

- How does one establish pikuach nefesh that is docheh Shabbos?

- Shulchan Aruch (Orach Chayim 151:6) rules that since davening extends a person’s life, whereas a sword is meant to shorten one’s life, one may not bring a sword or long knife into shul. Is this a reason not to carry a gun in shul? Tzitz Eliezer (10:18) concludes that a) when possible, it is preferable not to bring a gun into shul altogether; b) if that is not feasible, leave the gun unloaded and covered (based on Elya Rabbah cited in Mishnah Berurah ad loc); c) if that, too, is not an option, then just cover the weapon. He adds that all of the above does not apply when the weapon is being carried for protection. In such cases, one may enter the shul with the weapon, but it is preferable to keep it covered.

- Since a gun shoots a bullet by making a small explosion, it is prohibited to fire a gun on Shabbos under the prohibition against igniting a fire [unless it’s for the sake of preserving a Jew’s life]. As such, a gun would seem to be a k’li shemelachto l’issur, an object whose primary purpose is for an action forbidden on Shabbos. Rav Shlomo Zalman Auerbach ztz”l, however, (Shemiras Shabbos K’hilchasah 20:28) holds that a gun’s primary purpose is intimidation, and that a gun is therefore not muktzeh since intimidation is a permitted use.

- Shulchan Aruch (ibid. 301:7) rules that one may not carry weapons on Shabbos outside because weapons are considered a burden [and not clothing or an ornament]. Aruch HaShulchan (301:51), however, holds that a weapon is considered a soldier’s clothing during wartime [provided that he is not holding it in his hands]. His opinion, however, is not universally accepted. [Interestingly, Rav Moshe Feinstein (Igros Moshe Orach Chayim 4:81) allows Hatzolah members to wear radios on Shabbos without an eiruv, since an object can be considered an ornament (tachshit) if it indicates one’s rank. The Hatzolah radio points to the fact that the person is honorable since he volunteers to save lives. This logic does not apply to weapons.]

- All opinions agree that one may carry a weapon in order to save lives, since saving the life of a Jews takes precedence over [almost] all the Torah’s laws. The Shulchan Aruch (Orach Chayim 328:13) states that it is commendable to be quick to violate Shabbos where there is a life-threatening danger. [See also Rema ibid. 6] But in the present situation in the US, what level of sakanah exists? This is the question that every rav must decide.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 762)

Oops! We could not locate your form.