Building Blocks of Creation

| October 18, 2022Before the world existed, Hashem set up the alef-beis — the building blocks of the universe

“Bereishis bara Elokim es...”

Ask any elementary school student. They’ll readily translate this pasuk for you, they’ll even sing it in a cute chant. But the layers of meaning behind these opening words of the Torah fill volumes. I recall that in 12th grade, we spent the entire first semester on the first pasuk in the Torah. And while we thought we had delved so extensively into its depths, we’d only scratched the surface.

The Maggid of Mezritch in Ohr Torah explains:

“Bereishis” was also a creation. It is known among the kabbalistic seforim that the Hebrew letters were created first, and that Hashem then created the worlds using the letters. This is the meaning of “Bereishis bara Elokim es... — in the beginning, Hashem created “es” — Alef to Tav.

Before the world existed, Hashem set up the alef-beis — the building blocks of the universe. Like the chemical elements that make up the physical world, each letter of the Hebrew alphabet represents another dimension of reality. And each combination of characters — each word or name by which something was called — resulted in a different material that was actualized in creation (Sefer Yetzirah). In creation, the object was not given a name; the name formed the object.

The Rambam explains that when Hashem “spoke,” it actually means that an idea existed in His will and came to be. Hashem thought “Adam”: a combination of alef, for Oneness and G-dliness, and dam, for blood and physicality. And instantly, there it was!

Handprint of Hashem

Look at the ABCs, l’havdil. What is the significance of the shape of the “A” (two diagonal lines and one horizontal one)? Does it matter that G is the seventh letter? Of course not; there is no meaning in the Roman alphabet.

Not so with the alef-beis. Its letters are not a mere set of characters used to represent sounds. Each letter was tailor-made and then chosen to be used in the words where it appears.

In English, the word hand tells us nothing about what a hand is, its function, its appearance. It’s an arbitrary combination of letters used to indicate the part of the body at the end of the arm.

By contrast, the Hebrew word yad is made of the letters yud and daled. Daled has a numerical value of four, representing the four large fingers. Yud is the smallest letter in the alef-beis and looks similar to the thumb. The word yad tells us that this body part is made of four fingers plus one little thumb attached to them.

This is why it is so difficult to translate a Hebrew word or any Torah concept into a foreign language. The translation can never adequately convey the information contained in the formula that is the Hebrew name.

Creation Continues

Hashem not only created an alef-beis, He created a world of people who can use those letters to effect change — mirroring what He did. Chazal often use the term “olam katan — a miniature world” to describe a human being. Ibn Ezra writes (Shemos 25:40):

One who knows the secret of the human soul and the structure of the human body is able to understand something of the upper worlds, for the human being is in the image of a small world.

Just as the world we see before us is a composite of the various spiritual forces of the alef-beis, every one of us contains measures of each of those forces — we each have an alef-beis within us. There’s a spiritual flow that emanates from human beings, a reality we bring into the world through our actions.

Thoughts are intangible. But by expressing our thoughts, we concretize an abstract idea and make it impactful. In other words, when I think something nice about you, I am not affecting the world in any way. But when I turn my thought into an act and compliment you, I do affect the environment. Similarly, you may look at a picture and view it one way, but hearing my opinion could alter your perception of that photograph.

When we speak, we change reality. Through speech, a unique medium given only to humans, we can make a lasting impact, for good or bad. This expression of information, attitudes, and perspectives allows us to create. Positive speech brings good into the world. Misusing the power of speech — by insulting, using inappropriate language, or gossiping — also affects the world. The Torah teaches that we do not have complete freedom of speech. Words can build, or they can hurt; we must use our words with care.

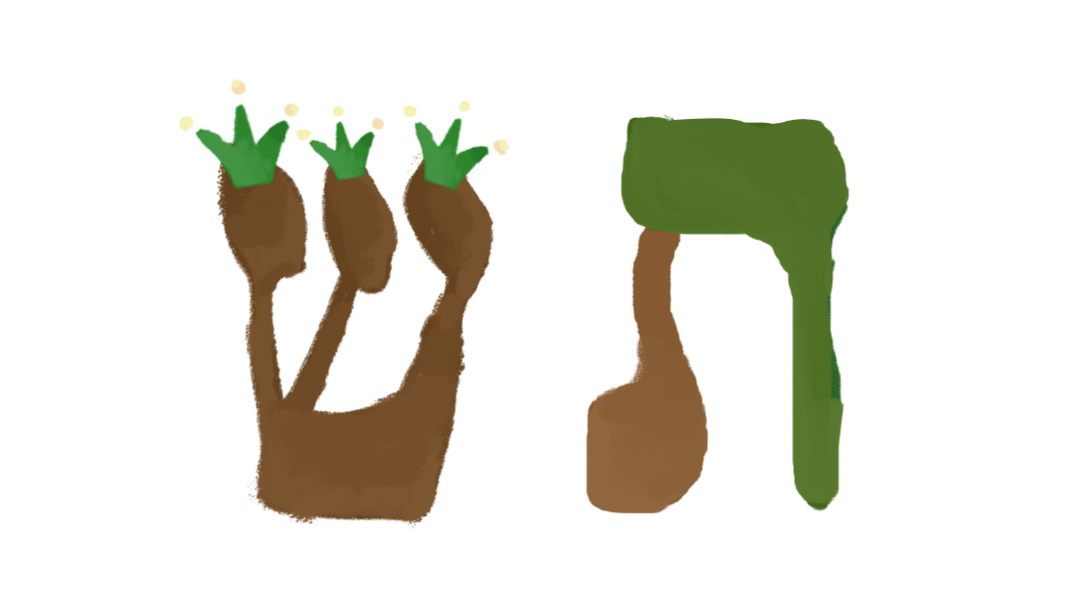

Journey Through the Alef-Beis

In describing how Hashem sustained Klal Yisrael in the desert, the pasuk (Shemos 16:16) tells us that He provided them with manna, “Ish l’fi ochlo — each man according to his needs.” The Baal Haturim points out that this pasuk contains all 22 letters of the alef-beis (a rare occurrence). The manna was a daily reminder that Hashem cares for us on an individual basis, and as the quintessential example of how He’s constantly directing events, with every consideration in mind, it is described using the letters from alef to tav. Hashem sees the world as a complete system in which each element has unique significance and works in harmony with every other element.

The term “alef to tav” is an expression of completion, of totality. In Eishes Chayil, Shlomo Hamelech uses the entire alphabet to describe the ideal woman, one who has mastered all the elements of who she is. When we study the meaning behind the letters, we are in effect learning about the spiritual components that make up who we are and how to incorporate each one into our lives. We can take these abstract ideas of letters and language and bring them into the realm of practice, of action.

When I was growing up, my family owned an old children’s book that told the story of the alef-beis in a magical way. Each letter was an actual character with a body and a personality.

Today I know that the silly stories do not come from a Torah source, as I had always assumed. But experience has taught me that while children’s books may be a fantastical expression of one author’s imaginative mind, they are often based on a kernel of truth. While the author of this book was not a Torah-true Jew, she touched on a world of depth in her description of the letters as individual personalities. Letters are real, vibrant, living things with a persona and a power.

I invite you to join me as we explore the significance of each letter’s name, shape, gematria (numerical value), and position in the alef-beis. We’ll also delve into the middah that each letter represents so we can come to a deeper understanding of what we’re actually made of — and how to harness that middah to build ourselves.

(Originally featured in Family First, Issue 814)

Oops! We could not locate your form.