Before a Wedding

They were European, so there was nothing, and I mean nothing, that went past them

Being in the event-planning business provides you with a bird’s-eye view you wouldn’t normally have of other family dynamics. In helping clients plan their celebrations, I often became privy to more information than I wanted or needed to know. It’s like that with any business that allows people to talk their hearts out — and sometimes even those that don’t.

I’d meet with clients at my dining room table, and we’d sit, schmooze, and work. I always made sure they knew that “what gets said at this table stays at this table” — a cardinal rule that came down from Sinai, and far be it from me to transgress it. After we shared so much, each client I was working with became my best friend, and many have remained so to this very day.

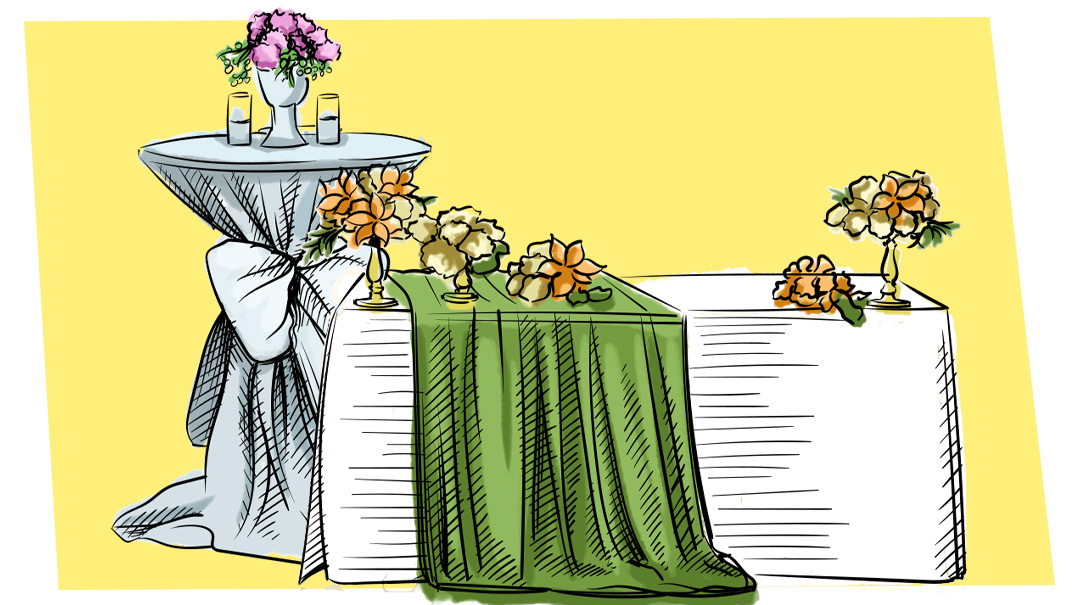

Some of my clients were children of Holocaust survivors — a group all our own — and as an unprecedented gift, many would invite their mothers (or maybe the mothers invited themselves) to accompany us to choose the fill-in-the-blank — venue, caterer, florist, musicians, photographers, etc.

When the grandmothers were present at these planning meetings, things sometimes took, let’s say, just a bit longer. These magnificent women had met and married their spouses, rebuilt lives, established homes, attended PTA meetings with their American counterparts, and tried their best to fit into American culture. They’d accepted their losses with a grace and strength beyond human measure while baking cookies and adapting and attempting to pretend that mass murders and annihilation hadn’t happened. That alone deserves a standing ovation. And now, they were being invited to help plan their granddaughters’ weddings. How incredible!

There had to be an allowance for “when I got married after the war, there were no parents, and we all wore the same simple wedding dress that had to be altered to each of us…” to the “our menu consisted of salami sandwiches — if we were lucky,” spoken in an accent heavier than the snow you hoped wouldn’t fall during the balmy Cleveland winters.

Kudos must go to the service-providers themselves who not only allowed, but welcomed these remarkable heroes and sat and listened and even expressed interest.

I always loved these women. We shared so much common history (I, too, am a child of survivors, and let’s face it — we’re different). Because they were European, there was nothing, and I mean nothing, that went past them. They’d notice everything from the fingerprints on the front glass door (“This will be cleaned, right?”) to the doorman at the hotel (“I can tell he’s an anti-Semite”). And they brought new meaning to first impressions and second opinions, both of which they freely shared.

Their daughters — the mothers of the respective brides — had their work cut out for them. They had to deal with brides (!), their own bourgeoning families, and satisfying their own mothers, whose standards and expectations were always on a plane all their own.

One of my favorites was Marilyn (we all had American names) and her mother, Mrs. Dolman. From the moment we began the meetings and the planning, Mrs. Dolman’s laughing eyes would start dancing. She relished every detail, from helping to choose the venue to examining the texture of the tablecloths. Her discerning eye would approve or disapprove, and believe me, you wanted the former rather than the latter.

Mrs. Dolman’s specialty was the menu. As a former culinary doyen par-excellence (she cooked in the shul kitchen for years and was famous for her farfel with fried onions and sautéed mushrooms), each course was chosen with the serious hushed tones reserved for Hungarian recipes that were never written down (Heaven forfend!), but rather whispered into progenies’ ears, and even then, only when absolutely necessary.

The presentation had to be perfect. “It’s not a barn,” she’d proclaim. The plate could not look too empty — or too full. “It should look colorful and heppetizing,” she’d say, pronounced with an inflection only slightly thicker than the bejeweled and plump fingers. Her drumming fingers and enamel-red painted nails would peek through behind the plate where she would position her hand.

When it came to the ultimate taste testing, however, we were inevitably on our own. When the caterer would offer his pièce de résistance, dessert of course, for our approval, Mrs. Dolman’s arm would rise up, bracelets sliding toward the inked numbers her sleeve barely covered.

With the fingers of her hand in a raised “Stop” position, she would demurely look away. With all the finesse she could muster, she’d raise her nose, close her eyes, move her head slightly and deliberately in the direction away from where we were sitting and coyly, but assuredly, proclaim, “S’cuse me. I’m before a vedding!” before breaking into hearty laughter.

This phenomenal woman truly understood that taking oneself too seriously is a sin.

This unparalleled phrase — “S’cuse me. I’m before a vedding!” has now wound its way into our private familial vocabulary. It is solemnly intoned when a family member is offered a special treat at any point before an upcoming wedding, and the phrase itself always quickens my anticipation of witnessing the future homes on our horizons.

It’s a welcome memory that allows me to recall, with nostalgia and delight, the happiness and laughter of the true champions who live among us.

L’chayim, Mrs. Dolman — and mazel tov!

(Originally featured in Family First, Issue 785)

Oops! We could not locate your form.