Diary of Defiance

A secret diary. A fearless Nazi hunter. An unknown Jewish grandson. Robert Scott Kellner finally honors his grandfather’s deathbed wish

In the thick of World War II, a mid-level official named Friedrich Kellner risked his life to pen his secret diaries, one man’s battle against Germany’s path to dictatorship and genocide. Years later, in intersecting lives filled with pain and challenge, Robert Scott Kellner, Friedrich’s Jewish grandson, has finally fulfilled his grandfather’s last wish

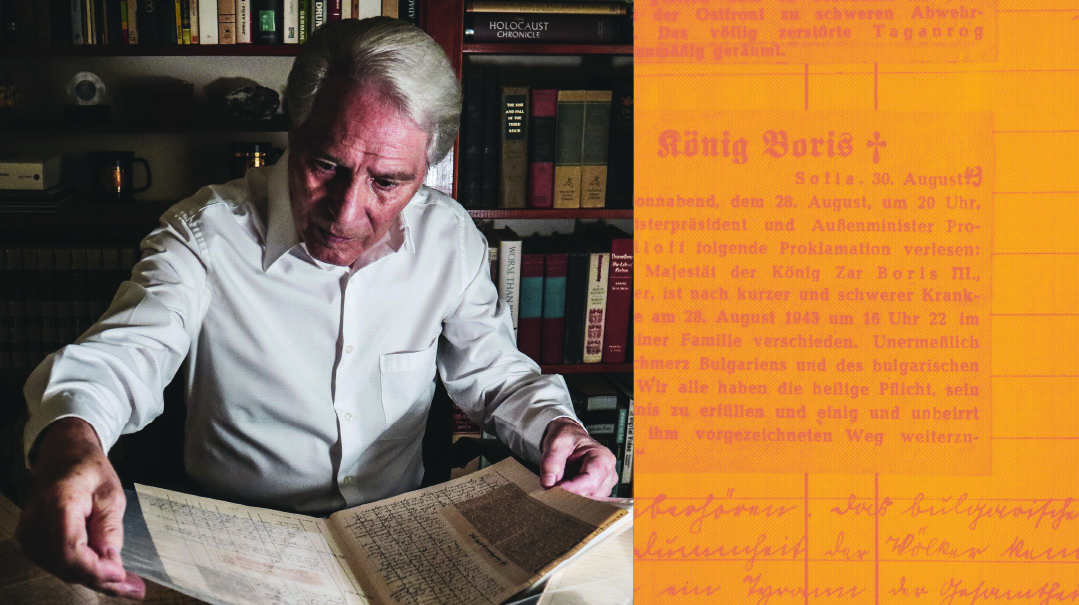

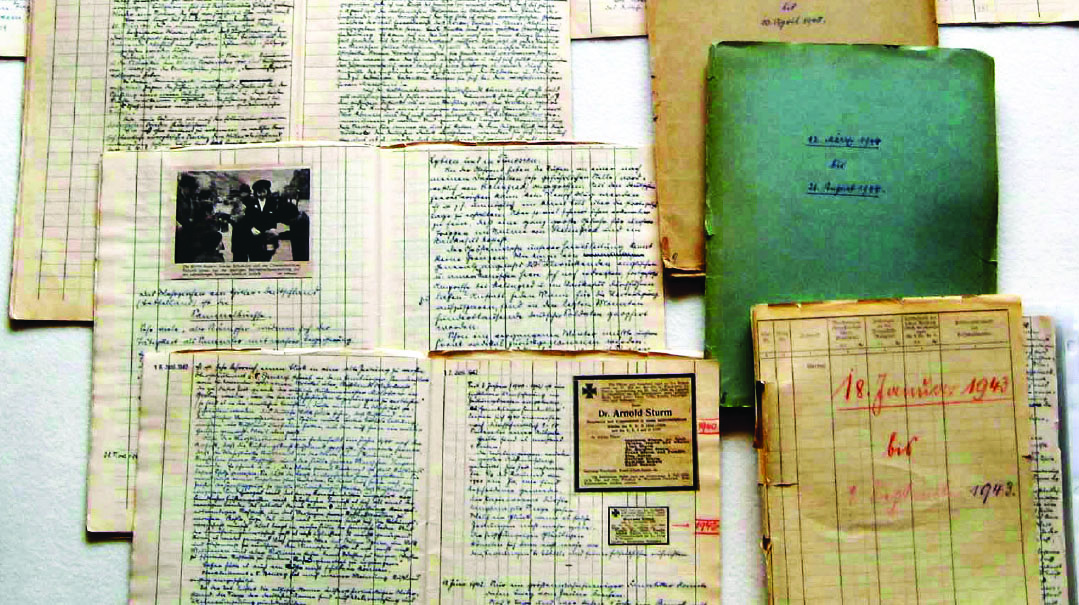

In an airtight vault of a Wells-Fargo bank in College Station, Texas, lies a treasure. It’s not gold or a crown or jewels, and someone looking in from the outside might wonder at the value of a bunch of yellowed bundles of old ledger paper penned with thousands of lines in now-antiquated German script. But for Dr. Robert Scott Kellner, a retired English professor at Texas A&M University, it’s a precious heirloom of historic proportions. And for the past five decades, he’d been devoted to sharing its contents with whoever will pay attention.

These sheaves hold a sacred trust: They are the secret diary of Dr. Kellner’s grandfather, Nazi adversary Friedrich Kellner — one man’s courageous opposition to totalitarianism and the rise of the Third Reich.

A mid-level official in a provincial German town, Friedrich Kellner kept a stash of secret notebooks from 1939 to 1945, risking his life to record Germany’s path to dictatorship and genocide and to protest his countrymen’s complicity in the regime’s brutalities. Now, after an improbable and emotionally-wrenching series of events spanning nearly eight decades, Robert Scott Kellner, Friedrich Kellner’s Jewish grandson, has finally fulfilled his grandfather’s deathbed wish with the publication of those fragile folios in readable book form, by Cambridge University Press.

Dr. Kellner feels the diary has enduring significance, especially in these days of heightened, overt anti-Semitism. “My grandfather wanted his diary to serve as a guide, a warning, for the generations after him,” says Dr. Kellner, whose soft, whispery voice and positive disposition even in the face of crippling difficulties belies an early life fraught with profound personal challenges that could handily sink a lesser person.

Friedrich Kellner: The Moral Fight

Who was Friedrich Kellner? He was a social activist and Lutheran by birth who had no Jewish friends and few Jewish encounters. Yet from the outset, his diary shows his moral character as he warns of the planned genocide of Jews, when so many others were still in denial that Hitler’s intent was nothing short of extermination. The notebooks were a courageous act of defiance in the face of terror — Friedrich felt that if he couldn’t stop the spread of madness in the present, by documenting it carefully he might at least have an impact on the future.

Friedrich Kellner and his wife Pauline married in 1913, and soon afterward he fought with the German army in World War I. He was a patriot and had a love of law and justice, but the high toll of the war bothered him, and the ensuing anarchy prompted him to join the short-lived Weimar Republic’s Social Democratic party.

When Hitler began his rise to power, Kellner, a justice inspector, clearly foresaw what was to become of his beloved country. He read Hitler’s manifesto Mein Kampf, which laid out the future Fuhrer’s diabolical doctrine, and he understood the horror that would ensue were absolute power handed over to this madman.

But most of his countrymen were swept up by the Nazi movement — even the Kellners’ only son, Fred. In 1930, when Fred was 14, he became an activist promoting the Nazi takeover of the world, an ideology that was sweeping across Germany like an epidemic. Desperate to distance their Fred from Nazi influence, his parents sent him to America. Little did they know that it would be many long years until they’d see him again, or that his life would wind up in shambles.

Meanwhile, in 1933, Friedrich and Pauline moved from their native Mainz, where they’d been active in the Socialist Democratic Party, to the small town of Laubach. There, Friedrich became administrator of the courthouse, which included an apartment for the Kellners downstairs and the judge’s residence upstairs. And just in time: One of Hitler’s first moves after being elected chancellor was to ban the leaders of the Socialist Democratic party, jailing and even murdering them. Both Friedrich and Pauline, who made no secret of their hatred of Nazis, faced tremendous pressure to join the Nazi party in Laubach; but as murderous as they were, the Nazis realized they couldn’t go around killing all mid-level officials — all they could do was warn Friedrich to keep his opinions to himself.

Friedrich knew he had to stay under the radar, but he revolted in his own way — through his secret notebooks.

“I knew that if I could not fight them in the present, then I would fight them in the future. If I couldn’t stop their propaganda, I could at least reveal their lies so that future generations would have a better chance against their own Nazis. This would be my rejection of terror, my opposition…

“You, people of Germany, gave yourselves up in 1933. That is your wicked sin. Indict yourself, Germany, cry over your own stupidity, submissiveness, fear, and cowardice… Hitler laid out in his book his disdain for the general public, but despite that, the masses go to him and yell, Heil Hitler! Just like the dumb calf electing its own butcher…”

Already in 1935, when the Nuremburg laws stripped Jews of their citizenship and made them an easy target for terror, Friedrich knew what that portended. Three years later, on Kristallnacht, as Nazi thugs raced through Laubach destroying homes and burning the synagogue, the Kellners were horrified. They went upstairs to the judge’s apartment to try to get him to stop the rampage, but he slammed the door in their faces.

After publicly advocating for the Jews, the Kellners’ ancestry was searched — was there some Jewish blood in the family? Friedrich Kellner had baptism documents going back 300 years, but he was still suspect.

With the invasion of Poland in 1939, Friedrich’s prediction became a brutal reality. At that point, he was summoned to the regional director of the Nazi party for questioning, where he was threatened with deportation to a concentration camp if he continued to openly state his political opinions. Pauline, for her part, was convinced that their lives were in danger and that their house would be searched, and to protect her husband, she took dozens of his diary pages and threw them into the fireplace. She hid the rest in her shirt. When he came home and saw what had happened, he went upstairs, took out another notebook, and began to rewrite what had been destroyed.

Finally, after four years of war and the accompanying atrocities and genocide, as the Allies began conquering Germany, they’d drop leaflets into open fields, asking citizens to assist them in ending the war. After each of these air-raids, Friedrich would gather the leaflets, risking imprisonment, and redistribute them in much more public places, like buses and trains. With the Allied advance, Hitler’s grip was finally unraveling.

“I knew that if Hitler would win the war, he would rewrite history to cover up his murders… and if he lost, all his accomplices would, in their own best interests, minimize their Nazi crimes or pretend they never happened. My diary would tell the truth, so that my grandchildren, and other children in the world, would have a torch and a weapon to light their way through the darkness.”

After the war, the Kellners built a small home in Laubach, away from the courthouse and the painful memories.

That same year, their son’s family was about to fall apart.

Robert Scott Kellner: A Lost Childhood

In 1937, Fred Kellner, a young German living on American shores, would meet and marry a Jewish girl named Freda Schulman, and they would have three children in a span of four years — a girl and two boys. The youngest was Robert Scott Kellner, born in 1941. Fred didn’t acknowledge that his children were technically Jewish — in fact, he insisted they be baptized. But he was an unstable father and abandoned the family for good when Scott was just three; a year later, Freda did the same thing.

“My mother decided she wanted to be a carnival dancer, but that meant she had to be free of the burden of three small children,” Dr. Kellner tells Mishpacha today, sounding more thoughtful than sad about his lost childhood. “So she took us to the Jewish Children’s Home in New Haven, Connecticut, and basically left us there. I remember that I couldn’t believe she’d just leave us, but she did. She didn’t linger or say goodbye, she just disappeared. I never got the feeling that she even felt bad about it — she had her dreams in front of her and wanted to pursue them.”

Dr. Kellner remembers that the children’s home was surrounded by a fence, and when he’d look beyond the fence, he’d see a normal world outside, a world with families and parents and love and stability. “I realized even back then that I’d never get rescued from this place, and that if I ever wanted to be on the other side of that fence on Sherman Avenue, I’d have to climb the fence myself and make my way in that normal world.”

That realization — even when times were tough, almost unbearable — kept him going and years later fueled him to build a productive and functional life for himself. He remembers that when he got a little bigger, the staff at the Children’s Home allowed him to go out on Halloween night and knock on doors asking for candy. But for little Scott, it wasn’t about the candy — what really pulled him was those glances beyond the front door into other people’s homes.

“There were families, parents and children who were giving treats to kids they never met,” says Dr. Kellner today as he surveys his well-appointed home in College Station, Texas, and gratefully considers his wife of 52 years and his own two daughters and grandchildren. “I saw those living rooms and it gave me a motivation to reach for that kind of life.”

But there would be many more bumps in the road until that happened. One day, the Kellner children were gathered together by the staff and told that their father had come to visit.

“He told us that he’d just arrived from Germany, that he’d come back to bring the family back together and take us back to Germany with him,” Dr. Kellner remembers. “But years later I learned that he never had any intention of taking us back. He was really a secret Nazi and during the war tried to spy for Germany. Once the FBI got wind of him, he joined the US military to prove his allegiance to the country. At the time he came to visit us, he’d joined a US military installation in Nuremberg, went AWOL, married a French woman, had another daughter, and did business on the black market. He’d come back to the US to ‘go shopping’ for black market goods, and had no intention of taking us back — although my sister, who was eight at the time, always harbored the hope that he’d be back. We were in the institution for another six years, and for all those years she waited for him.”

The Kellner children spent a total of seven years under the fearful fist of a superintendent with a terrible temper and a violent streak. But Dr. Kellner, ever charitable, never blaming, just moving forward, is forgiving — even of the man who could have beaten him to a pulp.

“Today I realize that he had a hard life — he wasn’t an innately terrible person. I even have a picture of him while I’m on his shoulders at the beach, and we’re having a great time. I believe he just didn’t know how to handle so many wild kids at once. He thought harsh discipline was the way to go.”

The other residents were mostly children from broken homes, and some were World War II orphans, but in general, they were only there for a few months until their parents or guardians could resume their care.

For the Kellner kids, it was a full seven years of misery. Until they too were sent away.

In 1953, when Scott was 12, the children’s home found out that their mother had remarried — to a much younger Irish carnival worker she’d met just a week before they tied the knot. Once the home learned that she was married, they forced her to take her children back. Freda’s new husband, however, got more than he bargained for. When he discovered that he not only had a wife but had to take in her three kids, he skipped out on her and joined the Air Force.

“It was a pretty miserable time,” Dr. Kellner recalls. “And to top it off, we got word that our dad was dead. He’d left his second wife, failed in business, and took his own life. My mom couldn’t understand why we were so sad. ‘He was a good-for-nothing Nazi,’ she said. But my sister was devastated — all those years later, she was still waiting for him to keep his promise to rescue us.”

Dr. Kellner’s sister got married at 17 in order to leave home, and his brother, a year younger, left at the same time. Two years later, at 16, Dr. Kellner was also a high school dropout and was living alone on the streets of New York, a time he calls “a pretty scary period in my life.” But, he says gratefully, the Navy saved him.

“Back then the US Navy would let you come in at 17, as a wild kid with no high school diploma,” he relates. “The Navy immediately straightened me out. It was a wonderful chance to make a good life for myself. Finally, I had a place, a support base, three square meals a day.”

After two years of training, in 1960, 19-year-old Scott was deployed overseas to Saudi Arabia, with a stopover in Frankfurt, Germany. Those were to become the most transformative days of his life.

“I Was No Nazi”

For Scott, this was an opportunity he just couldn’t miss; he had to find his German grandparents. He didn’t speak a word of German, so he began his search with just one clue: a scrap of paper on which he’d written “Laubach” — the only piece of information he knew about them, other than their names. He didn’t know that there were actually six towns called Laubach, and by the time he’d traveled to three of them, he was ready to give up. But then, as he was sitting on a train headed for a town called Hungen, he met up with a teenage brother and sister — Ursula and Peter Cronberger (he’s still in touch with them). They were intrigued by his American sailor suit, and yes, they lived in Laubach and yes, Friedrich and Pauline Kellner were their parents’ neighbors!

Ursula and Peter took Scott home and explained the story to their parents, who decided to first approach the elder Kellners without Scott — the couple had become reclusive and depressed, especially after their son’s death several years before, and it seemed wise to ascertain they really wanted to meet with this American soldier who claimed he was their long-lost grandson.

As Scott walked up the path to their home, he was both excited and apprehensive. “Grandparents!” he remembers thinking to himself. “If they were really mine, then it meant I was attached to something. On the other hand, I was nervous. I knew nothing about them other than that Friedrich had been a justice inspector, so I assumed he was a Nazi, and I had to prepare to forgive him.”

As the elderly, grief-stricken couple took in the young man at their door, something shifted within them: An American child of their troubled yet beloved son — could it be? Any doubt about this young fellow’s identity vanished when Scott produced the picture he’d always carried with him — his father, in a different, happier time, two decades earlier, holding his sister as a baby. Fred had sent that same picture to his parents, and it was right there in their photo album.

Scott spent the next four days with them. Friedrich knew a smattering of English from working with the occupying forces after the war as deputy mayor of the town, so that, together with two dictionaries Friedrich brought out plus a lot of love and patience, they slowly figured out how to communicate.

It didn’t take more than a few minutes for Friedrich to explain to his grandson what he’d really done during the war. “Ich war kein Nazi — I was no Nazi!” he stated emphatically, and then, as if to prove it, he went to a cabinet and hauled out ten full manuscripts. On the cover page of the first Friedrich had written “Mein Widerstand — My Opposition.”

“It didn’t take me long to realize that this was some kind of diary he’d written in resistance to the Nazis, and from the way he was still guarding it, obviously at great peril to himself during the darkest time in modern history,” Dr. Kellner relates.

During the four-day visit, the senior Kellners also learned the truth of what happened to their son in America. They knew he’d married and had children, and had even received a letter or two from their daughter-in-law, but until they met their grandson, they had no idea that Fred had married a Jewish woman, or that the children had been abandoned and raised in an orphanage.

When Friedrich learned that his grandchildren were Jewish, he turned to his wife and said, “So he married a Jewish woman — at least he did something right.”

As the visit came to an end, Dr. Kellner was left with an order from his grandparents.

“They insisted I go to school, that I get a proper education, and that somehow, I would help them bring attention to these diaries, which my grandfather really wrote as a legacy for the future,” says Dr. Kellner. “And my grandmother insisted that because I’d grown up in an orphanage, I had a responsibility to give back to society, to find other orphaned children, care for them, and treat them kindly — perhaps kinder than the treatment I myself had received.”

Robert Scott Kellner would spend the next sixty years using those promises as a compass for his own future.

More Responsible

“After the Navy, I was determined to become responsible and fulfill my grandparents’ wishes,” says Dr. Kellner, “but I think that it was more than just the specifics of what they’d asked of me. Even before I met them, I knew I wanted to live my life in a healthier, more responsible way than I’d been raised.”

It started with the way he treated his own mother. True, she’d abandoned him, but he found the compassion to help her nevertheless. By the time Scott joined the Navy at 17, Freda’s second husband was long gone, along with his support, and so she asked her older son to support her.

“It was an extreme request after all she’d put us through, and expectedly, my brother, who was very embittered and resentful, flatly refused. But although I was just 17, I was determined not to get dragged down by the hurt and resentment,” Dr. Kellner says. “And so, once I joined the Navy, I requested that mother be listed as my dependent — and every month half my salary went to her. After the Navy, I told her I couldn’t support her anymore because I wanted to go to school, and, survivor that she was, she found another husband to support her.

“But I never regretted it,” he continues. “I never acted with recrimination toward her for putting us in a home, for abandoning us. For me, that was history. At the same time, my brother and sister, who both live in California today, remain embittered. Maybe because they were older and understood more about what they were missing and about betrayal, but even so, it’s tragic that throughout their lives they’re still suffering from their lack of a proper childhood. I took a different route — I knew that as an adult, I had to learn to take responsibility, but they never moved on. It’s very sad. My sister’s now 83, my brother is 82, and I’m 80. I guess they’ll go on like this until the end, but I’m grateful I was able to break the cycle.”

Scott Kellner spent the next 11 years moving on: He earned a high school equivalency diploma and put himself through school at the University of Massachusetts, earning a bachelor’s and master’s degree and finally a PhD in English literature and writing. He also studied and became fluent in German, and in 1968, he returned to Germany to visit his grandparents again. At that point, Friedrich gave him the diaries to take back home with him. Two years later, both Friedrich and Pauline passed away.

When Scott was 28, he married a Jewish woman named Bev Stein, who is still active as a program manager for passenger safety at Texas A&M University’s AgriLife Extension Service. And, ever loving and responsible, he cared for his in-laws like his own parents, taking his father-in-law into his home and tending to him during the last year of his life, and building an annex onto his home for his mother-in-law.

Just Too Massive

Meanwhile, the 860-page diary was looming large in the background, but the project was massive as he embarked on the transcribing and translating process. There were time constraints and other obstacles in the way, but in the interim, there was another promise: to care for orphaned children. And so, Dr. Kellner got thousands of students at Texas A&M to join him in sponsoring not just one child through one of the established children’s funds, but an entire village. They chose a little mining village in Colombia, South America, building a new well system and other vital infrastructures — and even received a personal accolade from then-President Ronald Reagan.

By the mid-1980s, Dr. Kellner realized he had to somehow get moving on the diary, but he couldn’t find a sponsor to assist in bringing the material to the public. One reason was that it just wasn’t readable. Friedrich had written his folios in the now-antiquated Sütterlin script, which no one reads today, so the first step was to have it transcribed before it could even be translated. “We’re talking about close to 1,000 pages of documents, plus another 1,000 pages of pictures and clippings,” Dr. Kellner says. “And all this had to be done before we could even begin to create a publishable biographical narrative.”

Several professors he approached were excited, but they had no time for such a massive project. Both Yad Vashem and the Holocaust Museum in Washington were interested in acquiring the diary, but they couldn’t promise that they’d ever publish it, and Dr. Kellner didn’t want to give it over to them just so that it would sit in an archive vault. One professor told him that it was just too massive and would never work as a book, but it could be put on microfiche in a library.

The breakthrough came in 2005 when Dr. Kellner decided to write to former president George H.W. Bush, a fellow Texan, offering the pages to be displayed in his nearby presidential library. “Former President Bush read the letter I’d sent with a dozen photos of the diary pages, and wrote on top of the page, ‘Can you see what Dr. Kellner has here? It sounds very interesting.’ And he sent it to the curator of his presidential library and museum.”

That led to several write-ups and a new public interest in what Friedrich Kellner had done so bravely under Nazi surveillance. In the town of Laubach, on the same street as the apartment/courthouse where the Kellners lived, the Heimat Museum has an exhibit of photographed pages of the diary; and in 2012, a street was even named after Friedrich. Meanwhile, with the help of four professors who worked on the original manuscript, the diary was finally published in German. It became the subject of a 2007 Canadian documentary, and even actor Kirk Douglas, who in his later years had returned to the Jewish faith of his childhood, wanted to get rights to it for his own production.

In fact, Douglas and Kellner spent five months and numerous conversations about rights to the diary, but in the end, Kellner turned him down.

“Mr. Douglas was in contact with the Holocaust Museum, who wanted the diary for themselves, and then he’d decide how to proceed with his own documentary,” Dr. Kellner relates. “We spoke many times, but I insisted the diary would be useless sitting in a museum collecting dust, only for the eyes of some stogy researchers. I wanted the world to see this diary — that’s what my grandfather wanted — and the museum had already told me they couldn’t help me publish it in English.”

Dr. Kellner’s dream finally came true in 2018, when Cambridge University Press agreed to publish an abridged 520-page English translation of My Opposition: The Diary of Friedrich Kellner. Dr. Kellner translated and edited it himself. Similar abridged versions have been published in Polish and Russian.

Dr. Kellner admits that the book does not contain the entire diary — the original was just too massive and intimidating for the average reader. “So I cut back most of the newspaper articles and cut back our research notes, which were themselves the size of a small novel.”

He says that to retain the integrity of the original work, he used his own literary judgments about the phrasing, “but because Friedrich was so impassioned when he was writing, it was relatively easy to stay on track. And because I fully agree with what he was saying, I had no difficulty keeping to the authenticity of his words.”

Light the Way

The fact that Kellner, a Jew, was the emissary who brought these words to life is not lost on him. “I consider it almost fated,” he says. “In his will, my grandfather wrote that he wanted me to have the diary. He realized that if he gave it to me, I’d find a way.”

Dr. Kellner didn’t just translate his grandfather’s words, he lives them too, speaking out fearlessly against anti-Semitism and hate. He is an outspoken and active supporter of Israel and even has a religious relative living in a settlement in the Southern Chevron Hills. While he is not religiously affiliated and admits that strong Jewish feelings aren’t part of his internal makeup at this point, he says he identifies as a Jew.

“I wish I could have the same feeling that my cousin has — when he took me to the Machpelah Cave on a recent visit to Israel, it was awesome — but I just can’t. Perhaps because something was taken away from me when I was young… Still, when I go to Israel, I feel like I belong. You know, I was in the children’s home in 1948, during Israel’s War of Independence. We were about 50 kids, and we’d march around the parking lot with sticks, singing ‘Come join the Jewish nation, come join the Jewish army, fight, fight, fight for Palestine!’ I guess part of that is still in my blood.”

Now, as anti-Semitism spreads like wildfire around the globe, and with brazen attacks against Jews on the rise, Dr. Kellner finds himself wondering: What would citizens do today if faced with another Kristallnacht? Would they stand up to the authorities and refuse to join the hate, as his brave grandparents did? Perhaps the words of Friedrich Kellner are more prescient than ever:

“My diary would tell the truth, so that my grandchildren, and other children in the world, would have a torch and a weapon to light their way through the darkness.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 864)

Oops! We could not locate your form.