Meal Requests

There hadn’t been much time to decide and even though Phyllis Lang wasn’t a spontaneous sort of person, the prospect of being quarantined in her apartment made this seem exciting

It was an assistant manager named Shaya Mauer who made the decision, though he’d never been charged with decision-making before. The real manager was at a convention and Mr. Feder’s son-in-law wasn’t answering calls and the Board of Health kept updating their protocols and eventually, Shaya stepped up.

He was sweating profusely, actual sweat which he felt trickling down his back, and he kept repeating that he didn’t see another way and he hoped Mr. Feder understood the pressure he was under, but that was it. As the most senior executive at The Cove in Morgan, New Jersey, it was his job to make the call.

He walked around the lobby with what he hoped was an appropriate expression on his face and informed them all, Palma the head nurse and Michelle from billing who’d been there longer than him and Jose from custodial services, that as of three p.m. the next day, the facility was closing.

Dr. Liu, the chief doctor, wrote an email suggesting that those residents who could return to their own homes should do so immediately, until the staff could come back.

All rehab sessions were canceled. They would tread water for a few days and hope it would pass quickly.

Shaya Mauer felt very leaderly as he said this, “We’ll tread water until it passes,” and over the course of the afternoon, he got sort of good at it, nodding his head, frowning, and assuring them that he would follow up by email with all relevant details about payment for March and the schedule for reopening.

The first day, he was calling it Corona-19, a fact that would embarrass him later, a blot on what had otherwise been a flawless performance. Mr. Feder himself called to commend him later, a few days after the large brass gates outside The Cove were locked and only a single back entrance remained open.

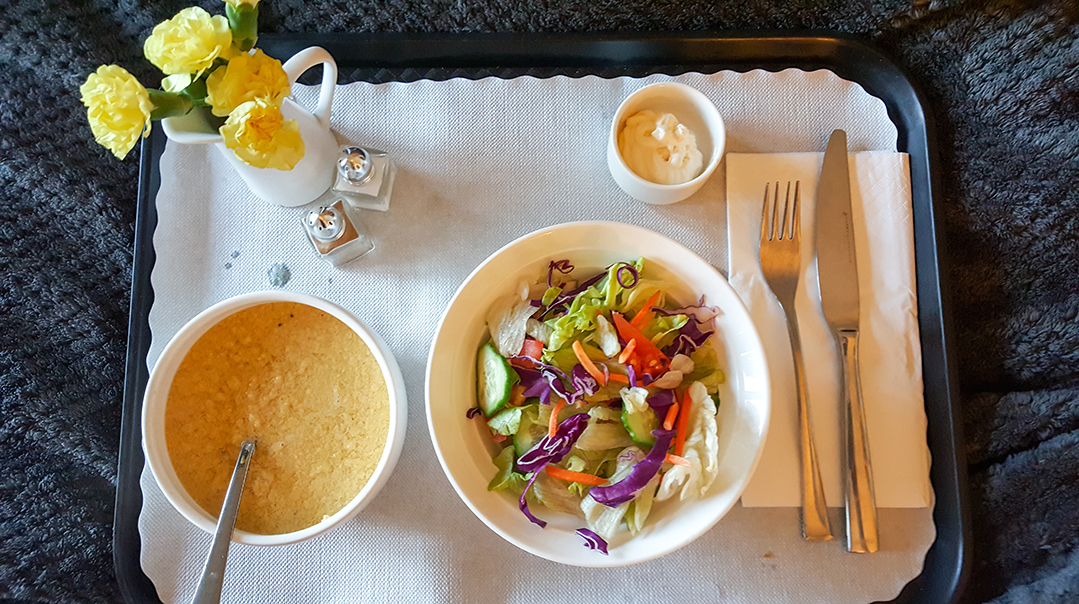

The Cove wasn’t a place that ordinary insurance plans covered, Shaya liked to tell people. Visitors were often awed by the décor and view, and the food, he liked to say, was “next level, better than any restaurant in the city.”

But on Tuesday March 17th, it was exactly like every other rehabilitation center — people speaking quietly, urgently, confidence shaken by the sense that something bigger than them was happening. Tammy and Barbara in admissions hated each other so much they’d barely spoken in months, but as they packed up to leave early on that Tuesday afternoon, Tammy smiled shakily and Barbara nodded and said, “I know.”

On Wednesday morning, the waves were like playful children, deep blue and white-rimmed and wilder than usual, but inside the low, gray building, the mood was somber. Minyanim and shiurim were cancelled along with all other activities, the hallways void of conversation, none of the thump-thump of walkers or clack-clack of wheelchairs. The PA system, usually a stream of music and announcements — they even had a “motivator” who came every week and filled the hallways with exuberant “you can do it” and “today is the day” stuff — was stilled.

Shaya Mauer, working from his home in Kensington, was overseeing the basic running of the facility.

Most clients had cleared out, returning to the relative safety of home and family. There were just a few left — the Horowitzes in 215 who preferred to remain in place, since they were too frightened to go anywhere, and Mrs. Shain, who didn’t have the strength yet to go anywhere. There was also the wealthy man from Argentina who didn’t really speak English, but he’d broken his legs while in Manhattan and so ended up at The Cove, the only fully kosher rehab center overlooking the gentle waves of the Atlantic Ocean. There were no flights home for him, so he was staying put.

Then there was Mordche Lemberger. That was tricky.

Oops! We could not locate your form.