Not Separate, Not Equal

Chassidic singer Motty Steinmetz became an unwitting hero in a fight he never anticipated. But it was about far more than a concert

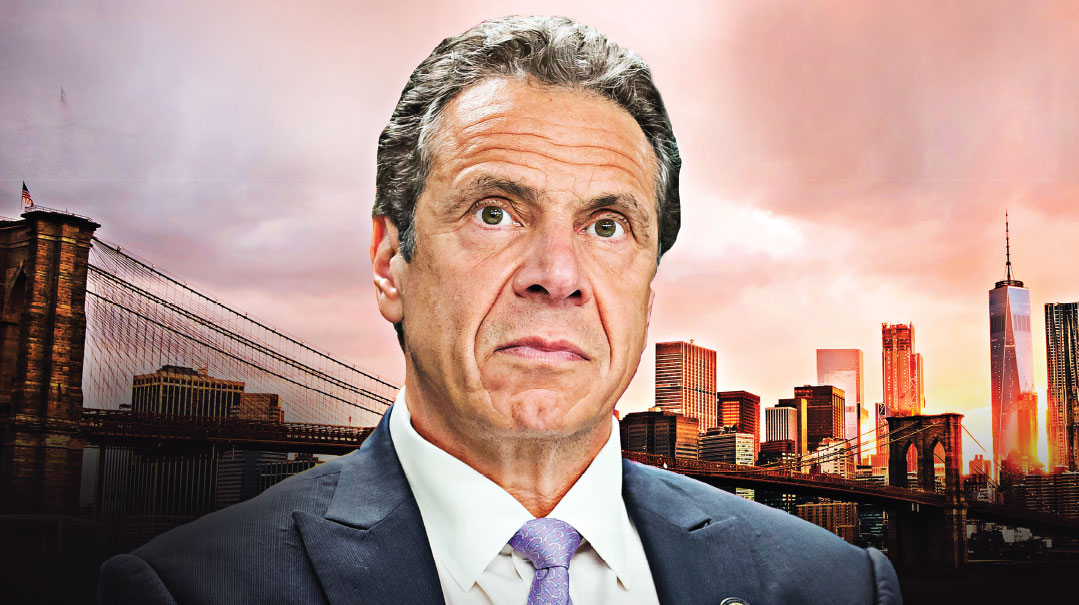

Photos: Itzik Blenitzky, Mickey Shpitzer

I

t was slated to be one of those typical bein hazmanim outdoor concerts where the singer has to balance between electrifying the crowd and keeping a level of decorum. But last Wednesday’s Motty Steinmetz concert in Afula’s amphitheater generated enough fireworks by its very happening to light up the sky.

It was a last-minute scramble following a week of court injunctions and appeals, instigated by the Israel Women’s Network feminist lobby, who petitioned against the separate seating at a municipality-sponsored event. It is inconceivable, they claimed, that in the State of Israel in 2019, a local authority should fund an event with mandatory separation of genders.

And Motty Steinmetz? He became an unwitting hero in a fight he never anticipated, and the focus of a secular public who, ironically, became exposed to his from-the-heart music in a way he never expected.

Every summer, local municipalities all over Israel sponsor cultural events for their residents. When the Nazareth District Court ruled on Tishah B’Av that the chareidi community may not hold a city-sponsored gender-segregated musical event at a public park — even as the Afula municipality supported the event, stating that out of over 300 sponsored events this summer, the city’s chareidi community was entitled to one that met its standards — Steinmetz made his own headlines by declaring he was canceling his performance.

That wasn’t the last word, though. The Shas party, together with the Kohelet Policy Forum, turned to the District Court to reverse its decision. They argued that the religious community is not seeking to force its lifestyle on anyone else, and that a High Court ruling prohibiting separate seating as a violation of the Basic Laws on Human Dignity and Liberty doesn’t apply to gender separation for religious purposes.

Just a few hours before the scheduled concert, the District Court reversed its previous decision, and Afula mayor Avi Alkabetz announced that the concert would be held with full gender segregation. The High Court, meanwhile, accepted the petition from the Women’s Network, overturning the local court’s decision — but it was too late: The High Court ruling came just as the concert was ending.

Reluctant Ambassador

The day after the concert that almost wasn’t, Motty and I meet in front of the Supreme Court complex in Jerusalem, where his heretofore unknown name in these parts has become an attention-grabber.

For many, the grand building in the center of this government complex is more than a courthouse — it’s a symbol of insidious judicial overreach. And by the same token, last week’s concert saga is not just about an isolated event in Afula that was nearly canceled by a legal order. It’s the story of an aggressive legal system that has repeatedly tried to thwart chareidi-lifestyle norms in almost every area, ironically using the same charge of discrimination and infringement of basic rights that chareidim claim are being trampled on their end.

Next up is an end-of-bein hazmanim men-only concert scheduled for August 26 in Haifa’s convention center, featuring Mordechai Ben David… and Motty Steinmetz. And again, the High Court will have to determine its legality, facing another petition from the Women’s Network.

When Motty Steinmetz and I walked through the plaza, we were followed by dozens of pairs of eyes. He’s used to being stopped on the streets of Geula or in Bnei Brak, but the people here hadn’t even heard of him until last week, when he found himself at the center of a state-versus-religion drama that riveted the entire country. In a sense, secular Israel discovered Steinmetz and his soulful singing — against the backdrop of legal efforts to silence him. Suddenly, every public media outlet was playing his songs.

“Hey, that’s the chareidi singer from Afula!” exclaims a young lawyer in jeans.

Motty Steinmetz smiles. “Not from Afula, from Bnei Brak,” he answers.

The lawyer’s gaze remains locked on the young chassid with his long peyos and chassidic rekel. “I heard one of your songs this week,” the lawyer continues. “What a voice. What intensity.”

A young security guard passing by asks, “Aren’t you Steinmetz?” Motty nods. “Explain to me, really, what’s the thing with the separate seats? Why am I, a secular citizen, supposed to let my tax money go to subsidize your event that excludes women?”

“Do you go to shul sometimes?” Motty asks.

The security guard nods. “Usually on the chagim,” he replies.

Motty continues. “And it’s okay that men and women sit separately, correct?”

Another nod.

“So, this is the thing,” Motty says. “From our perspective, a musical event is similar to tefillah. When we sing, we’re actually praying. We don’t sing about the trivialities of this world, or about dreams and personal aspirations, but rather about the endless yearning for the Creator, for the rebuilding of the Beit Hamikdash, for our hopes to grow in Torah. In chareidi eyes, a concert is a holy event of emotion and dveikut, not frivolity and lightheadedness.

“Our music is prayer. It is prayer from the deepest parts of the soul. When we gather together to sing, our souls are singing. We take the music, sanctify it, and bring it to a place that is closest to tefillah. Can you imagine such an event taking place in a way that does not suit our lifestyle?”

The security guard nods. He is quiet for a moment, and then answers, “Walla [wow], I understand. I see what you’re saying.”

I’m Not the Story

“It’s a little uncomfortable,” Motty tells me as we walk through the plaza. “Because I’m not the story here. Neither are the chareidi residents of Afula, who basically got slapped in the face by the Court. What did we want, after all is said and done? We didn’t ask them to have separate seating at their own events. We didn’t impose our standards on Tel Aviv or Caesarea. We didn’t interfere with any of the other summer events in Afula. All we wanted is to keep our traditions, in our own home, at our own event. And that isn’t acceptable to them either. So they issue a ruling that turns us into criminals and radicals.”

The court decision doesn’t mean that chareidim cannot hold separate-seating events at private venues. It does mandate, however, that if an event is sponsored by public funding or given a municipal venue, event organizers cannot force non-chareidi attendees to observe the gender-segregated measures that charedim might impose on themselves. That means no posting signs designating men’s and women’s areas, and no ushers directing people where to sit.

For Motty Steinmetz, 27, that was enough to compromise his principles, and he bowed out. Motty — Yisrael Baruch Mordechai Steinmetz — comes from a family of Vizhnitzer chassidim, and at every stage of his professional success, he has upheld the standards and hiddurim he observed in his childhood home. The Afula concert was one of a number of kumzitzes he’d planned for bein hazmanim, and nothing unusual seemed in the offing when the event was scheduled.

But then the petition was filed, and he realized a storm was brewing. During the Tishah B’Av fast, Steinmetz found out that the Court was hearing the case.

“It was clear where the winds were blowing in this court,” he says. “The timing of the hearing, on Tishah B’Av, was already a sign. Who schedules a hearing about a concert on Tishah B’Av? But of course, it goes much deeper. How is it possible that on a day Am Yisrael is mourning, the court schedules a hearing about a concert? As soon as we heard of the decision, we realized that the judge had ignored a clause in the law stating that separate events are permitted, legally, in places where it is the only opportunity for a sector to hold an event in this way.

“For me, the ramifications were clear,” Motty continues. “There are a few rules that I made for myself the day I began to perform on stage, and number one is that I won’t participate in an event that is not officially separate. No tricks, no shtick, no loopholes — period. For me, this has nothing to do with discrimination or exclusion. That is the tradition I was raised with — that’s how I was brought up and those are my principles. So for me, the implications of the ruling were clear. I wouldn’t be able to perform at the kumzitz in Afula.

“But you know,” he turns to me, “I wasn’t the victim here. The real victim was that huge crowd of chareidim who wanted to attend an authentic Jewish event during their summer vacation.”

Clear Boundaries

“I’m very happy and proud to be involved in creating and sharing authentic chassidic music,” says Motty. “But we only have the right to create and bring this music into Jewish homes when we adhere unequivocally to the guidelines of halachah and the clear boundaries that were established by gedolei Yisrael. There is no lack of chareidi artists who sing modern music. But a chassidic performer who maintains his authentic chassidic character and standards — there aren’t too many of them, and each of us has a huge responsibility.”

Only an insider can understand the challenge Motty faces. Every top singer gets dozens of invitations a month to events with mixed seating. But since he started in the industry, Motty has one ironclad rule: When there’s a question, there’s no question. Either the event is separate, or he doesn’t perform, regardless of the financial loss. Steinmetz relates that there isn’t a week that goes by when he doesn’t forfeit a lucrative event because of his principles.

“Of course there are challenges, but I approach them with a full sense of bitachon. After releasing ‘Nafshi’ with Ishay Ribo, he’s invited me lots of times to come and sing with him — at his events in Caesarea or in Heichal Hatarbut in Tel Aviv. But I always refuse because those events are not separate. Is it hard for me? Not at all. I don’t have even a tiny twinge of regret in my heart.

“I never felt like I was losing out because I maintained my principles — just the opposite. Some time ago, I went to Rav David Abuchatzeira, who outlined specific boundaries for me. One of the takanos Rabi David established for me was not to work on Shabbos, under any circumstances — and I don’t need to tell you that he wasn’t referring to chillul Shabbos. ‘When your work encroaches on Shabbos, it starts to take over your life, and that is not a good thing,’ Rabi David told me.

“I’m often invited to sing on Shabbos at all sorts of simchahs, but I knew that I had to listen to Rabi David. A short time later I received an invitation to sing on Shabbos in the home of a very wealthy Yid. I told him absolutely not, and baruch Hashem I’ve stuck to that.”

Culture Wars

Back on Tishah B’Av, when the court released its decision forbidding separate seating, reactions came fast and furious. Transportation Minister and United Right MK Betzalel Smotrich didn’t mince words, calling the court system “stupid” following the decision. “I’m sorry I couldn’t find a more delicate word,” he said. “Progressive, fundamental stupidity.”

“I’m sorry I couldn’t find more delicate words than progressive, fundamental stupidity,” said Transportation Minister Betzalel Smotrich about the ruling of the High Court (above)

Smotrich then called on all religious parties to tell Prime Minister Netanyahu that they are joining a coalition only on condition that legislation is passed that would allow gender-separate publicly funded events, “to put an end to secular coercion and to allow the religious community to live according to its beliefs.”

Democratic Union cochairwoman Stav Shaffir in return blasted Smotrich’s comments, saying that “he and his messianic ideology spell destruction for the legal and justice system,” and that Netanyahu was giving the religious parties control of the state “in return for the greatest political bribe in history — allowing him to escape the law.”

Yesh Atid leader Yair Lapid welcomed the court’s decision. “We will keep fighting for a Jewish, democratic, and liberal state,” he said. “This is not Iran.”

A senior Agudah MK explained to Mishpacha why this innocent concert in an out-of-the-way town sparked so much ire. “This isn’t about a concert,” he said. “It’s a culture clash. The issue is not this or that event. Over the last few years, the country has seen a steady erosion of anything that emits the scent of Yiddishkeit. There are groups here that speak in the name of freedom and progress, and they’ve been working to shift the red lines for anything related to religion.

“You see their fingerprints when it comes to the Kosel, the issue of public transportation on Shabbos, or programs meant for the chareidi sector. That’s why the battle here is not about holding a particular event. Yes, innocent Jews are suffering — they’re losing out on events and programs that they could have enjoyed. But the bigger issue is that the legal system is working hand in hand with these organizations to violate the Jewish character of the state.”

But for all that the Afula concert was just a minor skirmish in the bigger battle for the character of the country, the general public saw it an unforgiveable act. Senior secular journalists slammed the decision. Some mentioned government-funded cultural events in the Arab sector designated only for men, or only for women. Why the double standard, they demanded?

But the one who unwittingly became the ambassador of chareidi Jewry was none other than Motty Steinmetz himself. There wasn’t a news broadcast that did not begin with his name, and most of them included a few musical selections. With his newfound fame and headline status, he probably broke the glass ceiling for chareidi-chassidic singers in Israel.

It’s easy to get blinded by that kind of spotlight and media attention, and Motty Steinmetz is grateful for the spiritual giants who keep him focused. You cannot compare a crowd of tens of thousands of cheering fans to one personalized remark, short as it might be, from gedolei Torah v’chassidus, he says.

“Some time ago, I met the mekubal Rav Yaakov Ades,” he relates. “For forty minutes, he stood there giving me chizuk, telling me that he knows of hundreds of Jews who were saved from the worst sins because of my songs. I was moved to tears. The Rav asked me to start a telephone hotline for people who need a spiritual uplift through neginah. Then he composed a special tefillah for me to say before I go onstage.

“That same day, a friend asked me to come with him to the home of Rav Chaim Kanievsky. When I went inside, I asked for a brachah. Rav Chaim looked at me with his kind eyes and asked: ‘Do you learn?’ I replied, ‘Yes, but not enough.’ So he said, ‘Learn more.’ And I felt that in one day Hashem had sent me to two great gedolim. One gave me a stroke on the cheek, and the other gave me a mission, but both the stroke and the mission strengthen me in the same way — louder, longer, and stronger than the applause at the biggest concert I can imagine.” —

Under Separate Cover

While the Motty Steinmetz on-off-on concert captured national headlines last week, it wasn’t the first time that Israel’s Supreme Court has ruled against gender-separated events. The same story unfolded at a Simchas Beis Hashoeivah event featuring the brothers Yonatan and Aharon Razel in Jerusalem, and at a Selichos event that Chabad shluchim sought to hold on Erev Yom Kippur two years ago in Rabin Square in Tel Aviv.

But the most impactful ruling for the chareidi sector has been in the realm of higher education. In an effort to help chareidim integrate and excel in the workforce, special degree tracks in a diverse range of disciplines have been created, allowing this populace to obtain advanced degrees in gender-separated settings that accommodate their religious standards. Now, due to various civil liberty groups who’ve filed discrimination suits against Israel’s Council for Higher Education, the future of these gender-separated classrooms for the estimated 10,000 chareidi men and women studying for college degrees has been put on the line.

“This type of gender separation doesn’t interfere with anyone else’s lives,” Ariel Erlich, head of Kohelet’s litigation department, told Mishpacha. “We should honor freedom of choice and stop trying to engineer other people’s lifestyles.”

But in response to the pressure of the progressive liberal lobbies, the CHE has slapped limitations on the separate tracks, restricting them to bachelor-degree programs, and has ruled out separate extracurricular campus activities.

Where will this extreme activism lead, and who will pay the ultimate price? And perhaps more troubling — in their zeal to enforce some hazy concept of “freedom,” will the Court restrict an entire sector of society from financial mobility?

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 774)

Oops! We could not locate your form.