On the Giving End

M

ichal: Don’t you realize that all your gracious giving is causing pain and strain for us and our children?

Motti: We don’t judge you for not being able to give; please don’t judge us for what we have to give.

Michal

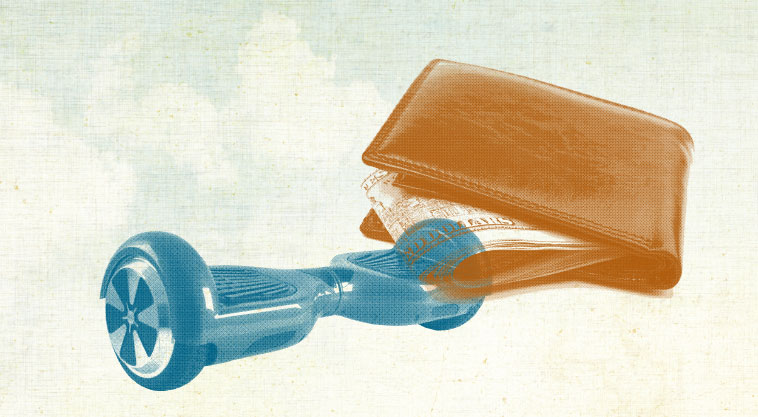

Yossi wanted a hoverboard.

“I understand, sweetie,” I said, for what felt like the tenth time. “It’s hard when your friends have something and you don’t. But it’s not something we can afford right now.”

Yossi was my oldest, at the beginning of eighth grade, and suddenly issues like money and brands and quality and what everyone else is buying or doing seemed to matter a whole lot.

He scowled. “It’s not fair. All the kids in my class have one. It’s so dumb to be the only one without it.”

I felt bad for him, I really did, but last month it was a new knapsack and the week before it was brand-name sneakers, of all things. We’d compromised on those, tried to give him something to make him feel we cared about his needs, but a hoverboard just wasn’t within our budget. And I couldn’t imagine that every other boy in his grade could afford it, either.

“Everyone? Or just a few boys?”

Yossi shrugged. “Almost everyone. Ariel got it first and now everyone’s getting. It’s so nerdy to ride a bike.”

“Why?” I asked Shua later, when the kids were finally asleep. “Why do people have to follow these trends? It’s one thing when the richest kid in the class has it, but it becomes a real peer pressure when there’s ten of them.”

If Ariel Goldman were the only one with a hoverboard, we wouldn’t have a problem explaining it to Yossi. The Goldmans are probably the wealthiest family in town, most of the mosdos in the city are supported by Motti Goldman, and he could afford to buy his kid a new hoverboard any day of the week. But we couldn’t, and I didn’t think we were alone there.

Shua went for the practical approach. “Tell Yossi he can use some of his bar mitzvah money if he wants a hoverboard. I bet that’s what his classmates are all doing, anyway.”

When I relayed the message, Yossi wasn’t happy. But that wasn’t anything new for him when the situation had anything to do with Ariel Goldman.

In the end, he did buy himself a hoverboard, which delighted his younger brothers, although he didn’t let them try it out for too long.

“It’s not a good one,” he complained. “Ariel and the other guys have better ones. With lights and stuff.”

I made a sympathetic noise. It really wasn’t fun, being on the receiving end of peer pressure. I wished that something could change. Couldn’t the school do anything about it?

“I think it’s just a matter of learning to live with it,” Shua said.

We were sitting down to prepare Chanukah gifts. Three sons, three rebbeim, three neat envelopes with a nice letter and $100 bill.

“I wish I knew how to explain that to Yossi.”

Yossi sauntered in just then. Shua handed him an envelope. “This is for Rabbi Stern, will you give it to him tomorrow?”

“Did you give your rebbi the envelope?” I asked Yossi, immediately when he came home. He made a face.

“Yeah, I did. Everyone had envelopes for him. Did we give him a gift inside?”

I was taken aback. “Were the boys in your grade talking about giving gifts?”

Yossi shrugged. “No. But I’m sure Ariel’s had something special inside, because Rebbi gave him such a nice thank-you, and when I gave him the envelope, he just said, ‘Shkoyach to your parents,’ all quietly, like he doesn’t really care about it.”

“I think you might be reading too much into that,” I told Yossi, but inside I wondered. Were the Goldmans setting the bar too high again? And would it affect how the rebbi treated his talmidim? How could our $100 compare with a $500 gift certificate to a silver store, for example?

“A good rebbi wouldn’t let it affect how he treats his students,” Shua said confidently. “Don’t worry about it, Michal. We gave what we could, it was a nice gift, within reason and within the norm. Let’s not take things out of proportion.”

***

But I was the one who was there each day when Yossi came home from yeshivah. And nearly every day, it seemed, there was another story.

“Ariel Goldman gets whatever he wants from the rebbi,” he complained once. “Whenever he raises his hand, Rebbi calls on him.”

Another day, it was recess. “Rebbi spent the whole recess with Ariel, reviewing the gemara we learned in class. And we all know why,” he said in disgust.

“Maybe Ariel didn’t understand it so well, so Rebbi was helping him out?” I suggested.

“But Rebbi never helps people out in recess, he goes to take a break. Except when it’s Ariel.” He kicked the table leg. “For sure because his parents are rich and they give so much money to the yeshivah.”

I was quiet, because it was hard to argue with that. Still, I assumed there was a real reason behind the recess learning session. Rabbi Stern was an experienced eighth-grade rebbi. In fact, that gave me an idea.

“Yossi has PTA next Monday,” I told Shua that night. “Maybe we can discuss this issue with his rebbi, the peer-pressure thing, the feeling like Ariel Goldman gets more attention, the whole insecurity issue.”

“Wait, next Monday? But that’s the night of the bar mitzvah.”

I had totally forgotten that. Shua’s only brother was making a bar mitzvah out of town that night. We planned to take the whole family for the simchah.

“I’ll work out another time to speak to the rebbi,” Shua told me.

The bar mitzvah was beautiful, and it was nice to spend some time with our out-of-town relatives. Yossi enjoyed being with his cousins and we ended up getting home even later than we had planned.

Shua sent Yossi to yeshivah the next day with a late note and a message for the rebbi.

“I’m writing here about the bar mitzvah, that’s why you’re late. And also that I’m sorry we couldn’t make it to PTA. Ask him if he could please write down on this note when it would be a good time in talk to him over the phone — maybe tonight?”

“Yeah, okay, whatever,” Yossi said. He didn’t look particularly happy. “But Rebbi doesn’t like me, I keep telling you that.”

“Well, maybe there’s something we can do about that.”

Yossi looked like he wanted to roll his eyes. “Yeah, like donate a new wing to the building…”

Shua was exasperated. “Don’t tell me this is about that Goldman kid again.”

Yossi didn’t answer, so Shua was probably right.

“He must be imagining it,” I said to Shua after he’d left the house. But I could hear the doubt in my own voice.

Yossi came home fuming. “I told you! I told you! I knew it!” he said, flinging his knapsack down. “I asked Rebbi for a time for Ta to call him, and he said he doesn’t have any time before Shabbos, Abba should try one evening next week. And then, at recess, I heard him tell Goldman to ask his father to call him tonight!” He came up for air, breathing hard. “I heard! He said, ‘Ariel, please ask your father to call me tonight.’ And then he said, ‘Don’t worry, it’s just instead of PTA, he missed it last night.’ It’s so unfair! Goldman gets special treatment because his father is rich. I knew it!”

This time I was angry too. And for once, I didn’t wait for Shua and his rational thinking, because I one hundred percent agreed with Yossi. How blatantly obvious could you get?

“The rebbi shouldn’t have done that,” my sister-in-law Breindy said, when I called her later and asked her what she thought of the story.

“But I can understand him,” I argued. “He doesn’t have much choice. The yeshivah probably insists that he keeps the Goldmans happy. After all, they just donated a new wing, they give the top prize for the Chinese auction, they come through when the budget isn’t adding up. The yeshivah needs them. I totally hear that. But aren’t they responsible here too? Don’t they see that their crazy lifestyle puts pressure on the other boys in the class? That not everyone can match their high standards? That their child isn’t the only one who needs the rebbi’s attention?”

Breindy agreed wholeheartedly. “You’re totally right there. It really isn’t fair, what’s happening. The other kids shouldn’t be the korbanos here.”

Yossi came into the kitchen just then. He looked down in the dumps.

“I have to go,” I told Breindy, and hung up the phone. But there was nothing I could say to Yossi to make things better. I’d thought the hoverboard was bad; now it seemed like the situation was even more complicated. And it didn’t look like anything was set to change anytime soon.

If I could tell the Goldmans one thing, it would be: I understand that things are easy for you financially. But don’t you realize that your good intentions aren’t very helpful when your gracious giving ends up causing pain and strain for us and our children?

Motti

“Ta?” Ariel peeked into the study. “Ta, the menahel’s on the phone, line one.”

I rubbed my temples. There was this constant headache behind my eyes, in my skull. Only three days until Shabbos…

“I’ll take it.”

“A guten, Reb Mordechai,” boomed the menahel. “I hope I’m catching you at a good time…?”

“Of course, of course, Rabbi Levi. What can I do for you?”

It was the right question, of course.

“Aahh, Reb Mordechai, shkoyach for asking. I’m just calling about the Chinese auction. They’re starting to work on the brochures….”

I sighed and figured I’d help the conversation along by going straight to the point. “You want a car again, for the top prize?”

The menahel sounded relieved that it had been so easy. “That would be gevaldig, Reb Mordechai, a groise shkoyach!”

“No problem. I’ll be in touch with — it’s Dov Newberg, isn’t it, on fundraising? — when I’ve made arrangements.”

At least that was quick, and I was happy to help out my son’s yeshivah. But when the phone rang again and again and again, I’d had enough. My family needed a break. I needed a break. I silenced the incoming calls.

“Too much pressure,” I grumbled to Leah. She made a sympathetic noise.

“I know. But baruch Hashem to be on the giving end, right?”

I nodded. “But we need to work something out, have some family time too. I get home crazy late and then the phone calls start?”

“People find it hard to reach you at work,” she pointed out.

“I know.”

“Ariel kept asking when you would be home, I think he wants to review his learning with you.”

“So see, it’s not great that people can reach me at home, that’s why I turned my phone off. Ariel doesn’t get enough attention, that’s not fair either.”

We had this discussion so often, we could probably just play an audio on repeat. Leah would tell me how lucky we were to be able to help people, I would tell her how torn I was with family responsibilities. We never really resolved it.

“I’m going to try sit with Ariel sometime this week, it’s really a priority,” I decided.

***

It was Wednesday evening, in that sliver of time between a late work meeting and Maariv, and I was finally sitting down.

“Great recipe, this,” I told Leah. She smiled. “It’s a new one I wanted to try out, from the magazine.”

Ariel was hanging around the kitchen, doing nothing. Leah glanced at him, and back at me, meaningfully. I put down my fork.

“Ariel? Everything okay?”

He looked pleased to be asked. “Sure, I just wanted to know when, um, if we could chazer together, I have a big test tomorrow….”

I felt so horribly torn, and so awful to disappoint him, but I had a meeting with the yeshivah board right after Maariv. I checked my watch.

“Is ten minutes any good?”

He looked crestfallen.

“Let’s just make a start, okay?”

We did that — he’s a good kid — but it wasn’t not enough, nowhere near enough. When we closed the gemara, I had this wrenching feeling that I had lost sight of what really mattered. Should I miss Maariv? Cancel the meeting, despite the late notice and the fact that roshei Yeshivah and major askanim are going to be there?

“It’s okay, Abba, I know you’re busy,” Ariel said, breaking into my thoughts and sounding far too mature for an eighth grader.

“I’m so sorry,” I told him, and I really meant it. “Would it help for you to learn with a rebbi or something… the one you studied with last year? We could hire…”

His face shuttered. “No. I don’t need one, I could study with my friends, I just… I’d rather do it with you.”

The clock ticked past nine o’clock. Late for Maariv. I pulled out a wad of bills.

“Ari, I’m proud of you, you’re learning so well. I wish I could study with you. Maybe over Shabbos we should sit down? Meanwhile, I’m giving you this in advance, I know you’re working hard for this test, buy yourself a hoverboard, okay?”

He smiled, but I knew it wasn’t good enough.

Leah heard about it, obviously, because she was waiting to speak to me as soon as I got in — much later than I’d intended, which wasn’t really a surprise.

“We can’t keep doing that,” she said. It was nice of her to say “we.” I knew what she was upset about. Another conversation we’d had before. “Money can’t compensate for you and a new hoverboard can’t take the place of a father.”

I took a deep breath. “I know. I promise, I’m not trying to do that. But I wanted to encourage him, show him I know how hard he’s working and how hard it is that I’m not around as much as I want to be. He deserves it, you know, he works hard.”

Leah nodded, we’re in agreement about that.

“And besides,” I continued. “I don’t want Ariel — or the girls — to feel like we’re generous with other people but stingy with them. Plus it’s not unreasonable stuff, a bike, a new game, you know?”

She knew. We both knew. And Ariel was happy, he thanked me for the hoverboard, and I spent an hour fighting sleep on Shabbos afternoon to learn with him. Leah appreciated it, and actually, I did too. I just wished the week wouldn’t bring so many conflicting pressures again…

***

The juggling act didn’t end, but I did try to come home early once a week, for Ariel and the other kids. As winter crept on and nights got darker and colder, it was nice to head home by six or seven, instead of eight or later.

“Almost Chanukah,” Leah commented one night. She slid a thick cream envelope across the table. “I wrote the thank-you card for Ariel’s rebbi. Want to put a check inside?”

“For sure, thanks for organizing.” I scribbled a check and slid it over for her approval.

“Wait, a thousand, you sure? Do we usually give that much?”

I shrugged. “I honestly don’t remember. Probably. Why not?”

She looked uncertain. “It’s… a lot, for a Chanukah gift.”

“You think the rebbi doesn’t know we can afford this?” I said. “What do you think he’s expecting from the Goldmans — a 50-dollar gift card?”

“You’re right,” she conceded, sealing the envelope. “I’ll send it with Ariel tomorrow. Thanks, Motti.”

Ariel was happy to deliver the gift. His rebbi was helping him out a lot, giving him some time during recess or whatever. I was glad we could show our appreciation. I was also looking forward to speaking to the rebbi a little at the upcoming PTA event.

“How’s school going?” I asked Ariel one night.

His smile was eager. “Good! Rebbi said I asked a great kasha today. He said he’s looking forward to seeing you tomorrow at PTA, that you’ll get lots of nachas!”

I beamed back at him, then suddenly frowned. “Wait, tomorrow night? Wasn’t PTA going to be next week?” I checked my calendar. “Uh oh…”

Ariel looked anxious. “What’s the matter, Ta? You can’t come?”

I was already dialing the menahel. Maybe we could make another arrangement for me to speak to the rebbi.

“I’ll put you in touch with Rabbi Stern,” he promised me. “Absolutely no problem, Reb Mordechai. For a friend like you, I’m sure we can accommodate.”

***

Ariel’s rebbi was warm and reassuring when he called that afternoon. “I completely understand, don’t worry at all. I actually have this every year, some fathers can’t make it and we schedule phone conversations in the evening to do a private PTA. If you want, I’ll put you down for the first evening.”

I checked my calendar. “That’s great. I’ll be in touch then.”

Ariel’s rebbi really cared. I liked that he scheduled the phone call and didn’t just tell me to “call anytime.” He even reminded Ariel the day after PTA, and of course, he gave a glowing report, which didn’t hurt.

So on that front, things were going well, and that helped me smile through another work day that ended late — emergency meeting and a phone call I’d been postponing far too long. Home time had never been so tempting.

The drive home took too long. I just wanted some peace and quiet already, a few minutes with the family. The house was quiet when I came home, quieter than usual. For a moment I thought there was no one home, but then Leah stepped out of the kitchen. Her eyes were a little red.

“Hi,” I said, squinting a little. Leah never cries.

“Motti, we need to talk,” she said abruptly.

“What’s going on?” I filled a glass with ice and poured myself a drink. What a day.

“I was at the gym today… people are talking. They think we’re throwing around money to get favors from the school, the rebbeim. I’m mortified. We need to stop.”

“Hold on, wait, slow down.” I pushed the cup away, too upset to drink. “Someone said that? In front of you? Who do they think they are? We have every right to choose how to use our money, it’s no one else’s business, and we’re certainly not wasting our time on—”

“It’s not like that,” she interrupted. “They didn’t blame me outright. But Br— one of the women, she kind of told me quietly that other people are resenting it. They think we’re buying favors from the hanhalah and rebbeim, getting special treatment for the kids even when they don’t deserve it and it’s not fair, pushing other kids down just because they don’t have what we do and making other parents feel all pressured…”

That was the wrong word.

“Pressure? Seriously?” I let out a bitter laugh. “What do they know about pressure? About expectations? About the principals and the askanim who don’t stop calling, about the expectations on us to give generously, about how we’d be looked at if we didn’t give so much, because everyone knows we have the money… remember that Purim? When we tried to tone down the mishloach monos and a ton of people ended up insulted, thinking we had given them less than other people?”

Leah looked uncomfortable. “I was thinking about that.”

I swished the juice in my glass; the ice cubes clinked together agitatedly. “Bottom line is, this is clean money earned honestly. We’re giving tzedakah, we’re using it to help people, that’s nothing to be ashamed of!”

She sighed. “You’re right. I just wish they’d understand.”

I thought of the space people left to me in shul, the way the chevreh sometimes went quiet when I walked in, like he’ll never understand our problems. Of the phone calls and the desperation and the aching gratitude and the cloying respect for my money that had nothing to do with me. Of the constant pressure and expectations, the eroded privacy thanks to all those public commitments.

“I don’t think they ever will,” I said, shrugging. And reached out for the Tylenol. The headache was back again, full force.

If I could tell the Kaplans one thing, it would be:

We don’t judge you for not being able to give — please don’t judge us for what we have to give.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 739)

Oops! We could not locate your form.