Dark Days in August

The Crown Heights riots, 30 years on

Photos: AP Images

The street names are the same but the principal players are not. The men who lived through the Crown Heights riots 30 years ago are changed for life. Some have gone on to the world of truth.

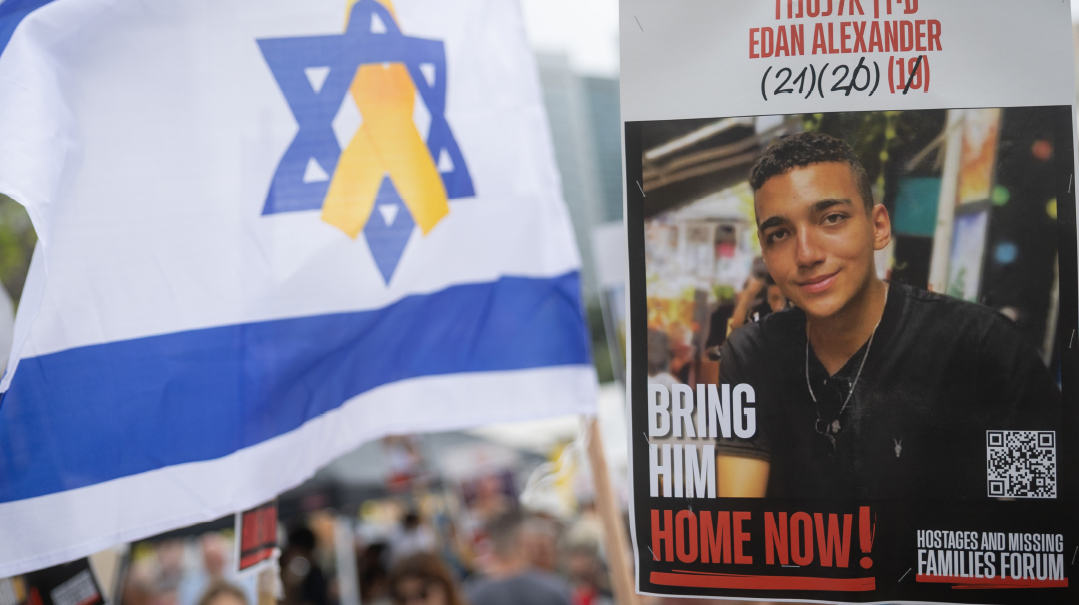

The nadir of the four days in August 1991 when Jews were scared to be seen outdoors on their own streets was the murder of Yankel Rosenbaum Hy”d. The 29-year-old researcher from Australia, whose 30th yahrtzeit was last Wednesday, was attacked by a mob as he was on his way home after Maariv.

Norman Rosenbaum, the young husband and father who took it upon himself to be the voice for justice for his brother from distant Melbourne, passed away last year. His oldest grandson is just ten years old, too young to grasp why his grandfather made the 23-hour trip from the Land Down Under to the Big Apple more than 250 times.

“Norman was a tzaddik,” said Rabbi Shea Hecht, chairman of Lubavitch’s educational arm and a spokesman for the community during that dark period. “If not for him, the city would not be the same.”

On August 19, 1991, B.B. King, a famous blues guitarist, was performing in Crown Heights as part of a series of concerts arranged by then–city councilman Marty Markowitz. The event attracted a large crowd from outside the neighborhood.

As revelers emerged from the concert hall, they heard news of an accident in which a black child, Gavin Cato, had been killed by a Jewish driver. A light rain had begun to fall, and a driver accompanying the motorcade of the Lubavitcher Rebbe, on his way back from Queens, had swerved to avoid oncoming traffic, killing Cato. In the mad dash to the scene, multiple rumors flew until a mob formed, yelling “Kill the Jews!”

Late that evening, Yankel Rosenbaum was set upon by a mob and stabbed five times. He died shortly afterward, but not before confronting his killer, Lemrick Nelson, asking, “Why did you do this to me?”

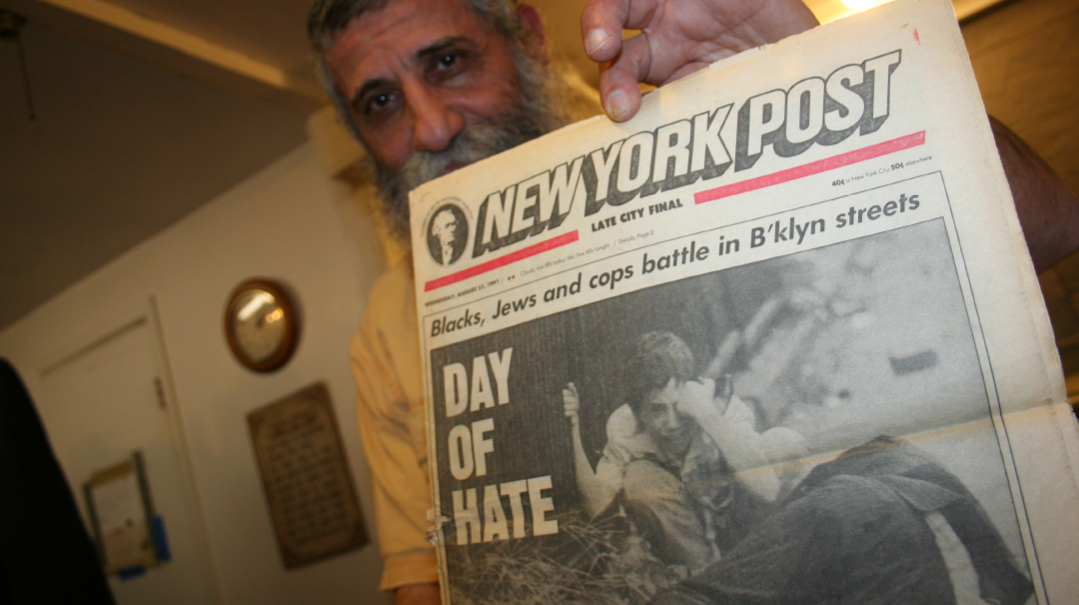

Riots broke out and continued for days. When Governor Mario Cuomo asked Mayor David Dinkins why this was allowed to occur, Dinkins replied, “We allowed them to vent their anger.”

Rabbi Hecht remembers all this vividly. Hundreds of members of his community, perhaps more, suffered trauma for years. Children grew up forever seared by the screams, seeing adults hiding in the closet, memories of the Holocaust echoed on the streets of New York.

Nelson Lemrick was convicted and served part of his sentence before it was thrown out on a technicality. But Norman Rosenbaum never believed that justice was served with Nelson’s jailing. He fingered another dozen perpetrators as participants in his brother’s mob stabbing.

Today, Crown Heights is a neighborhood where Jews and blacks still live side by side. Leaders of both communities insist that relations are amicable, and outside agitators are unwelcome. Rabbi Hecht looked back on those dark days and reflected on their meaning today.

What did the riots mean for you personally?

There was a moment in time when we felt that our community, our neighborhood, was not safe. There was a moment when we felt that the police department either wouldn’t or couldn’t protect us. We felt helpless about what was actually taking place on the streets.

The stabbing took place on Monday night, and for the next three days, until Thursday, things were crazy over here. We reached out to the mayor, and we did not get any response. We reached out to the governor, and we did not get any response. We reached out to every politician whom we were able to in order to put pressure on them.

Finally, Dinkins comes in to visit us on Thursday night. The police department did a sweep, they picked up 85 people, and the riots were over. They just went in, arrested everyone in sight, and the whole thing was over.

And then, we dealt with a lot of aftermath. Politicians were calling it a problem of homelessness, of bias, that Crown Heights is a powder keg, blah-blah-blah. We didn’t buy it. A lot of newspapers were writing that the Jews thought that the blacks are getting special attention from the government, and blacks thought that the Jews were getting special attention. In the meantime, both sides were shortchanged by the federal government, the state government, and city government.

At that point, after the riots ended, agencies started coming in and helping us out. I want to praise Dinkins in this area — he gave us police protection right away. And he gave us a lot of attention over the next year or so. Of course, after Giuliani came in, he picked that up a lot, and things became even better.

Howard Golden was then the Brooklyn borough president — he created something called the Crown Heights Coalition. I headed it from the Jewish side, and Edison O. Jackson — who was very respected at the time, he was president of Medgar Evers College for many years — represented the black community’s side. We worked for the next four years to encourage understanding among our two communities.

Did that bridge-building effort trickle down to the grassroots?

Yes, it trickled down. But our communities were never really in a fight with each other.

On the Wednesday afternoon during the riots, we had a press conference in our office. We lit candles for Gavin Cato.

One of things that I said to the press was, “Listen, what you see on the streets are not our people. This is not the Lubavitch community, this is not the chassidic community, this is also not the local black community. More or less, our neighbors get along with each other.”

I remember being challenged by some of the reporters. “Rabbi, you think we’re stupid, that we’re going to buy that garbage?”

I told them, “You can report whatever you want, I am telling you facts. The fact is that people living in this neighborhood get along.”

I remember Channel 4 News on Thursday went down Montgomery Street, from New York Avenue across to Albany Avenue. They knocked on every door, blacks and Jews, and asked them, “How do you get along with your neighbors?”

And by and large, whether it was a Jewish neighbor or a black neighbor, everyone basically said, “We generally get along. Do we have differences? Yes. But just normal problems that neighbors have.”

After that, the newsmen said, “You know what? Hecht was telling us the truth.”

I want to pick up on what you just said. I’m not in Crown Heights often, but when I am there, I see youths loitering on the streets who give me dirty looks. I don’t get this in any other neighborhood.

Wait. For the last eight years in general, but particularly in the last few years, when de Blasio was mayor, things got worse. If you want to talk to me about the 12 years of Bloomberg or the eight years of Giuliani — it was very, very good. Unfortunately, de Blasio has not helped racial relations. De Blasio hurt racial relations.

What you say goes against the grain, but I understand the philosophy.

Listen, I thought in November 2008, when Obama was elected, that racism was over. I thought, look, we now have a black president. What happened? The next eight years, we had the worst race riots that this country saw — in Baltimore, Dallas. And we’ve had some terrible, terrible moments in New York City in the last four years.

How do you feel when you hear David Dinkins being rehabilitated? When he died, there was an outpouring of affection. Mayor de Blasio has spoken positively about him. Even Eric Adams says that he’s his model for how he would be a mayor. How do you and your community in Crown Heights feel about this?

About Adams, I think you’re giving too much credence to what he said about Dinkins. Believe me, he is not going to run the city the way Dinkins ran the city. [Dinkins] was not his idol. Dinkins was a black mayor, and Adams is hoping to be the next black mayor. That’s all.

So let’s leave him alone. Over the past couple of years, people are giving Dinkins credit for bringing down crime, saying that he was the one who started sending extra cops onto the street. You yourself said that after the Crown Heights riots, he gave you better police protection. What are your feelings when hearing this?

I’m not sure. I don’t look at reality the way you look at reality. After a guy dies, they say nice things about him; you don’t talk about the bad things. Everybody knows that the city under his watch was out of control. Everybody knows that the Crown Heights riots happened because he was incompetent. Everybody knows that he didn’t let the police do what they had to do. Period.

Part of it was Lee Brown’s problem, but blameless he was not. You’re not talking about a Bill Bratton or a Ray Kelly, who were basically tough on crime but fell short in a different area.

The real question, and it is a big question, is: Will Eric Adams be tough on crime, being that he was a cop? He’s no fool, he knows what the story is.

You say that Dinkins deployed more cops. Do you know that the city’s murder rate was at a high of over 2,000 a year? There was much more black-on-black crime than there was black-on-Jew crime. You think he was worried about racial tensions? It was very simple what his problem was. His problem was that crime was out of hand, that murders were crazy high, and he realized that he better do something.

Yankel Rosenbaum would have been 59 today. His brother, Norman, unfortunately, isn’t with us anymore. The torch has sort of been passed on to the next generation. Does the next generation know enough about what happened in those days, in August 1991, to be able to learn its lessons?

No, they don’t. But if not for Norman, everybody would have forgotten what happened.

What about Al Sharpton, the self-styled communal activist who played a big part in instigating the violence back then and has gone on become a major figure in politics and media? Would you ever forgive him?

I have no comments about him. I did not want to honor him by talking about him.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 875)

Oops! We could not locate your form.