With Quill and Heart

Tradition is indelible for master sofer Rabbi Shmuel Schneid

Photos: Mordechai Hahn

When Rabbi Shmuel Schneid’s grandsons complete shnayim mikra v’echad targum for an entire Chumash, he’d give them a cash prize of $50. Then, when his granddaughters asked for an incentivized challenge of their own, he made them an offer: Learn how to kasher a chicken and be tested on it for a payoff double that of their brothers. Whether it’s writing a pair of tefillin or preparing a Shabbos meal, for Rabbi Schneid, a longtime sofer in Monsey, New York, tradition — how Jews actually lived and practiced their Yiddishkeit — is paramount.

Reb Shmuel is an expert practitioner of the Jewish scribal arts, but when it comes to defending the importance of minhag Yisrael, he’s “not stam.” He’s devoted decades to reclaiming age-old traditions regarding all things stam (the acronym used in halachah for “sifrei Torah, tefillin, and mezuzos) from historical obscurity, and has gained an international reputation as an impassioned advocate for their continuing relevance in our time.

Along his journey back into history, Reb Shmuel has inspired a whole new generation of safrus researchers. Rabbi Yehoshua Yankelewitz, a kollel yungerman from Bayit Vegan profiled in these pages last year for his avocation as a collector and student of sifrei Torah from across continents and historical eras, says it was Reb Shmuel Schneid’s tutelage that started him off.

“I’m part of a whole network of people who are experts in sifrei Torah, from directors at Sotheby’s to a rabbi in New Zealand to a rebbi in Beit Shemesh and a shochet in Munich, and nearly all of them, are talmidim of Rabbi Schneid,” says Rabbi Yankelewitz. “Some of them became his students even before I was born. They’re all world-class experts, and they all view him as their main rebbi in this area.”

The common thread that binds these geographically and culturally diverse talmidim of Reb Shmuel together is, according to Rabbi Yankelewitz, the “fascination, even obsession, with safrus that he sparked within us. The first thing a talmid of his does when he visits a community is to try to get a look at the sifrei Torah.”

Reb Shmuel’s home on a quiet Monsey street is a magnet for local yeshivah bochurim who, like Yehoshua so many years ago, go there just to hang out, so to speak, soaking in its atmosphere of halachic discovery and excitement. These inquisitive young men thrill to his descriptions of historical mysteries and halachic controversies and gain priceless knowledge about topics that are nearly entirely absent from the standard yeshivah curriculum.

“The geshmak with which he talks about these things makes the topic of stam infectious,” Reb Yehoshua says. “You can watch him talk about the most arcane halachic question — say, the exact form of the tagin, crowns, on the letter lamed — and he’s so obviously enjoying himself, repeating experiences and things he’s learned as if it were the most geshmak piece of news.”

Providential Encounter

Reb Shmuel’s childhood in the Bronx of the 1950s gave no indication of the role he’d find himself in today. He describes the home he was raised in as very traditional but confused Jewish-wise. His father put on tefillin every day but went to work on Shabbos. Shabbos itself was a day of contradictions.

“You could switch on lights,” he recalls, “but never ride a bike outside. But on Yom Kippur everything shut down in the house.”

Shmuel often went over to his grandparents’ home nearby, and he especially enjoyed spending time in the shtibel his grandfather davened in, a place where “there were old-time Yidden of the kind that simply doesn’t exist anymore. People with sterling middos and genuine, palpable yiras Shamayim.”

After attending a public elementary school, Shmuel went to high school at Yeshiva University’s Marsha Stern Talmudical Academy and then moved on to college at New York University. It was during those years that his interest in safrus was first piqued. One evening, he went into the local shul, the Moshulu Jewish Center, for Minchah and Maariv. During the break, he went into the social hall, where Rabbi Shmuel Rubenstein was speaking. Rabbi Rubinstein was a Bobover chassid and a sofer who gave talks on safrus to Talmud Torahs all over.

Shmuel and a friend listened to his talk, and afterward, they went over to him and asked him if he would be willing to teach them safrus. At first he refused, but then he reconsidered and made them a counteroffer. Rabbi Rubinstein was also a Jewish publishing pioneer, producing a whole series of soft-covered pamphlets, offering how-to guides on a host of different mitzvos like tefillin and kashrus, Shabbos and arba minim. He told the boys that if they would edit his booklets, he would teach them safrus.

The boys eagerly accepted the offer, and Rabbi Rubenstein showed Shmuel and his friend how to write the alef-beis. And that was the beginning of a priceless connection he gained to an entire world of old-time safrus that had been largely lost in World War II. Through Rabbi Rubenstein, Shmuel got to meet and learn from people like Rav Aharon Pollak, the undisputed expert in safrus in Satmar circles, and Rav Moshe Bick, the renowned posek in the East Bronx and later in Boro Park.

School of Life

Shmuel had always been drawn to hands-on skills, and while still in his twenties, he learned how to do milah and shechitah, too. When a fellow NYU student sitting next to him in class told him about a US government program that offered nearly tuition-free study abroad, Shmuel applied, and after landing a slot, went to learn in Eretz Yisrael.

During his year in yeshivah there, he joined an extracurricular class in shechitah because, as he puts it, “this was during the Vietnam War, and I figured at least if we get drafted, we’ll have what to eat.” Upon his return to the States, he began learning in Yeshivas Rabbeinu Yitzchok Elchanan (RIETS) under Rav Dovid Lifschitz and Rav Yosef Weiss.

In response to rumblings of opposition to milah at that time, a body known as the New York Milah Board sponsored a course in RIETS to teach circumcision and give mohelim the professional credentials they needed. While Shmuel had no intention of becoming a practicing mohel, he still took the course, and actually did the brissim for his own sons.

Reb Shmuel has strong opinions about what he sees as missed opportunities in today’s schools. “A guy spends 18 to 20 years in yeshivah altogether, and when he comes out, he can’t make a knot on his tefillin? He can’t put tzitzis on his tallis? A girl goes through all those years of school learning all this intellectual stuff and she doesn’t know how to kasher a chicken? She can’t kasher a pot? Every balabos in Europe knew more about actual Yiddishe living than these kids.

“When you learn a halachah sefer, it’s a bit like, l’havdil, reading the building code for the Town of Ramapo. A driveway has to be six feet wide, but that’s if it’s blacktop; if it’s gravel, it has to be seven and a half feet wide. You need to bring it alive. The Tiferes Yisrael writes in his introduction to Perek Ha’oreig in Shabbos, ‘Before I embarked on explaining this topic, I went to learn weaving, and now that I know how to weave, I can explain the mishnayos.’ ”

Lost Legacy

Through his exposure to expert sofrim like Rabbis Rubenstein and Pollak, an entire world of stam began to open up before Rabbi Schneid, replete with multiple traditions on every aspect of safrus. From the forms of the lettering to the methods and ingredients for producing the physical objects of our tashmishei kedushah, he learned that customs varied, sometimes widely, in Jewish communities around the globe.

Undertaking to closely study every sefer Torah he could get hold of, Reb Shmuel began comparing and contrasting them all, and slowly it began to dawn on him that there were entire styles of sacred writing that had been lost to history. The forms of scribal writing that everyone is familiar with are the standard Ashkenazi ksav, known as Beis Yosef, and another permutation of it called Arizal, and the Sephardi one, which actually includes as many different variations as there are Sephardi subcommunities.

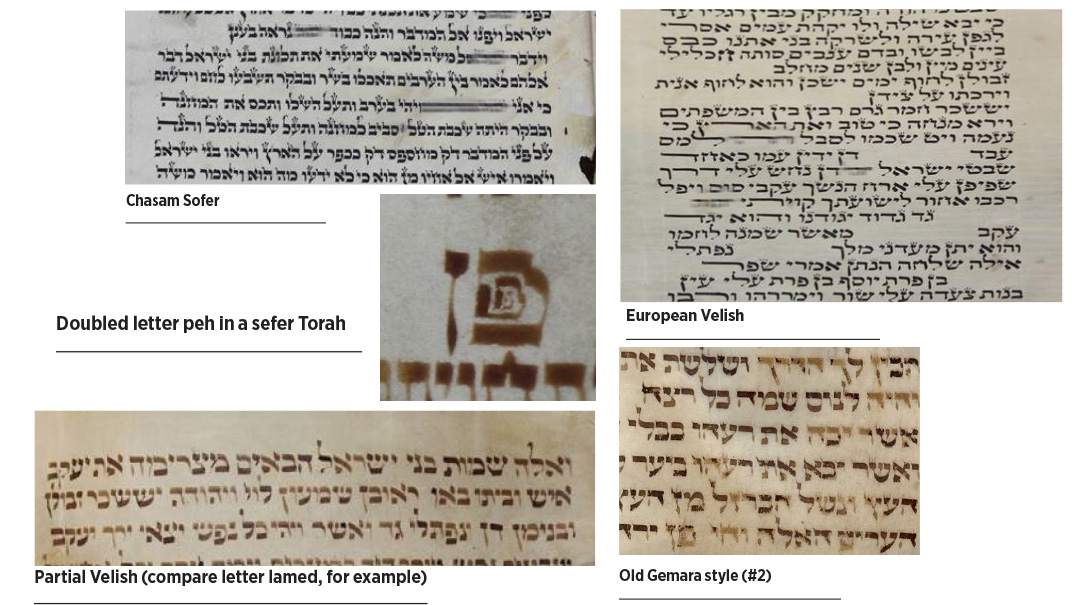

One major discovery by Rabbi Schneid, says Rabbi Yehoshua Yankelewitz, is that that in Germany there was yet another ksav that’s somewhere in between the Sephardi and modern Ashkenazi styles.

He also came to the conclusion that another ksav, which the Ashkenazi poskim call “Vellish,” a style similar to the Sephardi ksav, was used even in Lita, a stronghold of Ashkenazi traditions. He was also able to decipher the word “Vellish” itself, which apparently means “foreign” in old German. No less a distinguished litvishe personage than Rav Zundel Salanter testified to having read from a sefer Torah written in ksav Vellish in the Volozhin Yeshivah.

What’s more, Rabbi Schneid found sifrei Torah that were written in Ashkenazi ksav except for certain specific sections written in Vellish, with, for example, those sections that are read on the Yamim Noraim being written in Vellish. This means there was ksav Ashkenazi and ksav Vellish side by side in one sefer Torah.

“He was able to discover all of this because he has seen a greater variety of sifrei Torah than almost anyone I know,” says Rabbi Yankelewitz.

Rabbi Schneid’s expertise has taken him to far-flung locales to examine sifrei Torah from around the world and across the centuries. About a decade ago, he went along with Rabbi Yitzchok Reisman, a longtime Lower East Side sofer, to Oklahoma City, where the billionaire evangelical Christian family that owns the Hobby Lobby store chain had stored thousands of sifrei Torah they purchased in connection with the National Bible Museum they later established in Washington, D.C. Until the museum was ready, they kept these seforim in an Oklahoma City warehouse, and they brought out Rabbi Reisman to identify the date and location of the writing and to evaluate the condition and worth of each sefer Torah.

Reb Shmuel joined Reb Yitzchok on these trips as an assistant, and together they made five multi-day trips out to Oklahoma. Over the course of these visits, he got to see many hundreds of sifrei Torah that sofrim never get to see, from all over the world, from Uzbekistan, from Kurdistan, from Yemen, from 500 years ago, from 200 years ago. The differences, among these many sifrei Torah, in the kinds of klaf, the different ways of stitching, and of course in the lettering and sometimes even in the spelling, were visibly apparent.

“There were even differences in how the klaf is attached to the atzei chayim, “ Reb Shmuel says. “For sifrei Torah was from, let’s say, Romania or Czechoslovakia, the minhag was that the last yeriah is sown onto the etz chayim with a thin strip of klaf, not like they do it nowadays, using the giddin, the sinews that stitch together the yerios, to attach the klaf to the pole. I saw somewhere that it was intentionally done that way, with a strip of klaf, in order to show that the atzei chayim are not essential to the kashrus of the sefer Torah.”

Stolen Heritage

Another opportunity to see a collection of sifrei Torah came Rabbi Schneid’s way even earlier on, in 1997, when the Lithuanian government organized a commemoration marking 200 years since the petirah of the Vilna Gaon, hoping it would spur Jewish tourism to the country.

“It ended up being a very small frum delegation that went,” Reb Shmuel says, “but Ronnie Greenwald went, and I did too, in the hope of getting to see sifrei Torah in the possession of the Lithuanian government. The Jews claimed ownership of the sifrei Torah, but the Lithuanians responded that since the Jews were Lithuanians, the scrolls belonged to them. Never mind that they killed so many of these ‘fellow Lithuanians.’ ”

The delegation was given a tour of the national archives, where these sifrei Torah were housed, and Rabbi Greenwald arranged for them to be brought to kevurah. Normally, the Lithuanians would never have allowed the burial of these “official documents,” but Ronnie used his contacts — and large sums of money funneled to the proper people — to get permission for the kevurah.

“We were ushered into the storage area deep underground, where a very imposing-looking Lithuanian lady was standing guard at the door,” Reb Shmuel remembers. “They took out all the scrolls, and they were very well cared for, stored in very nice linen bags, as befitting a professional library. When I examined the sifrei Torah, I saw that there were no antiques there; they had all been written in the 1930s, and I told them so. But for me, it was an opportunity to see how prewar sofrim had done their work.

“We decided to stop and continue the next day, but as we were leaving, the lady guard suddenly says, ‘Nobody’s leaving — somebody took a Torah. You’ve got to be kidding, I thought to myself. This is ridiculous! Am I hiding a sefer Torah in my pocket? She claimed to have been counting the sifrei Torah that one was missing. Here we were, deep underground, being detained for suspicion of smuggling out a sefer Torah. The crisis was only resolved at last when someone realized that there was a sefer Torah upstairs in the chief librarian’s office.”

The delegation was also invited to the opening session of the Lithuanian Parliament, where they followed along with headphones providing simultaneous English translation.

“I recall it being a very intimidating environment,” Reb Shmuel says, “with lots of priests all wearing huge crosses on their chests. The Lithuanians themselves are a very tall people, and not very friendly to Jews, so it was very uncomfortable.”

A rav who was present spoke very nicely about the Gra and about yeshivos, and then the Israeli ambassador to Lithuania got up to speak. While everyone else was dressed in suits and ties, he was dressed very inappropriately for the occasion, with his shirt buttons open on his chest. Next thing Reb Shmuel knew, the ambassador started launched into his speech saying “that everyone knows the Nazis killed the Jews, but you killed them all before the Nazis got here.”

“I thought we would never leave that place alive,” Reb Shmuel says. “There was bedlam, with people slamming their headsets down and his words being broadcast on the radio. To this day, I don’t know what possessed him to do that. We managed to get out of the country, but that was very frightening.”

Gap in the Chain

Through his research into antique sifrei Torah, Reb Shmuel began to see various things appearing in the poskim in a new light. Things they wrote that seemed difficult to square with the stam we have nowadays suddenly became understandable if one assumed they had one of the older lettering styles in front of them.

But Reb Shmuel’s experience of learning from old-style European sofrim and seeing a multiplicity of stam from diverse communities around the world also left him very disturbed. He came to believe that after World War II, there was a break in the mesorah from that of prewar Europe, and that virtually all sofrim in the new generation learned hilchos stam from sofrim in Yerushalayim who hadn’t gone through the war.

Reb Shmuel claims that the traditions of the old European sofrim were lost, replaced by various chumras that were introduced for quality control purposes, as a way of standardizing the production of stam. Yet these were practices that the old-time sofrim wouldn’t have recognized. As he watched sifrei Torah that had been regarded as kosher, even mehudar, by prewar standards, now declared pasul, Rabbi Schneid grew upset.

“The old-time sofrim are no longer with us, and if the new sofrim don’t see the old seforim, what are they learning from? Today everyone learns from books, not from people,” Reb Shmuel observes with chagrin. “I always tell people that if I want to learn how to kasher a chicken, I’m not going to go to a rosh yeshivah. I’m going to go to somebody’s grandmother and see what she does. Then I’ll go back and learn Yoreh Dei’ah. And you’re not going to kasher a chicken by reading the side of the Diamond salt box.”

As Rabbi Yankelewitz explains, “Rabbi Schneid is fine with a later generation wanting to take on chumras, but what bothers him greatly is when a later generation doesn’t just become more frum than earlier ones, but then goes about declaring that things those earlier Jews did as a l’chatchilah, or even as being mehudar, are not even kosher bedieved. He has a profound respect for the previous generations and their minhagim, and when he sees people lacking that respect, he’s deeply disturbed by that.”

New but Not Necessarily Improved

Rabbi Schneid says that the area of safrus is “a microcosm of how things are in halachah generally, which is the ever-increasing number of chumras that were never followed before.”

He cites as an example the push to have retzuos that are black on both sides. He agrees that there is a shitah that holds that, and those promoting this will say you have to be concerned the retzuah will turn over. “But,” he says, “did we worry about that before?

“The new sifrei Torah have a huge space between the columns, which isn’t like the old Torahs that have a two-finger-wide space between them, because they decided to use the Chazon Ish’s shiur. But why? There are sifrei Torah from all over the world that have the smaller space, and you don’t see any with the bigger space.

“Or take the very idea of having to check your tefillin. Now, I’m a sofer, and I get paid for checking tefillin. But why are people doing that? Sure, it says in halachah that one should check his tefillin twice in seven years, but read the fine print: That’s only true of tefillin that you don’t use, but not tefillin that you use regularly, because you’re only checking for ipush (mold), and that’s not possible with tefillin you use every day.”

The halachah is like the Rambam, Rabbi Schneid emphasizes, who wrote “einan tzrichim bedikah olamis — they never need to be checked.” He says that he feels very strongly about people keeping their minhagim, and that he definitely isn’t trying to deter those whose custom it is to check their tefillin from doing so. He cites the Chabad minhag to check their tefillin every Elul, and that some hold that a chassan checks his tefillin before the chasunah, and of course there are instances when something happens in a person’s life and his rebbe or rosh yeshivah advises him to check his tefillin.

“But if you want to talk halachah,” he says, “Hashem gave us lots of mitzvos and Chazal gave us more dikdukim to do — stop adding on to it. And then you end up thinking that’s the halachah, when it’s not the halachah.”

Rabbi Schneid says that what he learned from the derech of Rav Bick and the others I mentioned was to ask, “How can I be machshir these tefillin?”

He tells us about a friend of his, a sofer, who asked Rav Neuschloss, the old rav of Skver, a sh’eilah about letters touching in a sefer Torah. Rav Neuschloss responded that he doesn’t know this area, and the sofer should ask Rav Aharon Pollak. Rav Pollak, too, said he was very unsure, and he needed time to think about it. So Rabbi Schneid’s friend decided he would just rewrite the yeriah. When Rav Pollak heard that, he got very upset.

“What? Rewrite the yeriah?!” he said. “Do you know how many of Hashem’s Sheimos there are on this yeriah? That’s not an option; we have to answer the sh’eilah.”

Leave It Be

Nevertheless, the deep reverence Rabbi Schneid displays for what has been handed down through the generations sometimes means, perhaps paradoxically, that one has to let things stand just as they are, rather than restoring them to how they once were. He illustrates the point with the story of a local family whose son was seriously injured in an accident. The boy’s grandfather owned a pair of very old tefillin that he kept as a segulah, and when the accident occurred, the boy’s father asked him for them for the boy to wear.

But the grandfather said he felt he needed to hold onto them because that’s what was keeping him alive, and after 120, the grandson could have them.

“After the zeide passed away, they brought the tefillin to me, and when I opened them, I saw they had been ‘fixed.’ That is, originally it had a double pei — a pei inside a pei — which some sofer had removed. I was going to change it back, but Rav Aharon Pollak said to me, ‘These tefillin were written by one of the Baal Shem Tov’s sofrim, and anything he wrote I’m not fixing. I’m not touching it,’ adding that had the tefillin not been ‘fixed,’ he could put it on the table in Satmar and immediately get $100,000 for them.”

Rabbi Schneid is far from alone in his efforts to uphold the traditions of safrus against the new homogenizing trends. He cites such highly respected Torah figures in the Monsey community as Rav Chaim Flohr, Rav Mendel Morris, and his longtime neighbor Rav Shabsi Wigder as giving him halachic support and encouragement over the years.

“Rav Chaim Flohr had a collection of Russian tefillin that he gave to a sofer to check, and in two of the words that contain the letter pei, it’s written as a double pei. Also in the word ‘vechara,’ the ches had little feet-like extensions on either side of the letter. When the sofer returned the tefillin, he said he’d fixed the parshiyos.

“Rav Chaim asked, ‘What did you fix?’

“ ‘I removed the inner pei and cut off the feet of the ches,’ the sofer replied.

“Rav Flohr was incredulous. ‘Why’d you do that?!’

“But that’s what the new generation of sofrim are doing, redoing all the tefillin that came from Europe, as if the gedolim of Europe didn’t know what they were doing. What are they thinking? We’re not smarter than them.”

Mystery Solved

With a creatively fertile mind and unquenchable curiosity for anything related to stam, Reb Shmuel is constantly sleuthing about for answers to riddles of halachah and minhag.

Once, he recalls, he was standing in line at the butcher shop when two of Rav Chaim Flohr’s sons said to him, “The Rosh says you can make ink out of just two ingredients: guma, usually translated as gum arabic, and afatzim, gall nuts.”

“I said, ‘No, that doesn’t work. Gum arabic and gall nut powder, how does that make a black ink? It’s the third ingredient, kankantum, that makes it black.’

“So listen to the siyata d’Shmaya. I went one day to help make a minyan at the Teimanim, and I hear the sheliach tzibbur saying Kedushah — Gadosh, gadosh, gadosh. So I see that they pronounce the kuf like a gimmel. I looked in the mishnah in Megillah and on the list of ink ingredients is something called kumus. Now, some mefarshim like the Tiferes Yisrael translate that as gum arabic, but the Rambam in his commentary to the Mishnah says it’s a type of kankantum, which in Arabic is called ‘alchiber.’ The Kaf Hachaim, too, writes that kankantum is ‘alchiber.’ So I believe the Rosh, who moved from Germany to Spain, was using the Arabic pronunciation for kumus, so he wrote guma, which, substituting a gimmel for a kuf, is like kuma. He’s not referring to gum arabic, but to a type of kankantum called kumus.”

Then there’s the time Reb Shmuel opened up a pair of tefillin from his collection and accidently pulled on the retzua of the shel rosh.

“Lo and behold, it moved,” he remembers. “I realized that this was a one-size-fits-all shel rosh, with an adjustable retzua. The Avnei Nezer says this is pasul because there’s supposed to be a kesher, a knot, not an anivah, which is like a bow.

“But a few years later, I was teaching my safrus class in Yeshiva University when one of the Moroccan students said, ‘In Marrakesh we had a kesher tefillin like you never saw, with an adjustable strap.’

“I said I did see it, but in Russian tefillin. A few years after that, I was giving another class, and another Moroccan tells me that his brother in Tetwan, Morocco, sent him a letter telling him they have their own way to make the kesher, which he showed me.

“Fast-forward a few years, and I get a call from Eretz Yisrael, from someone who tells me in his rich Yerushalmi Yiddish that he’s part of a chaburah working on kesharim there, and he wants to know if I know anything about a sliding kesher. So I sent him ten samples of the adjustable one and of the other one that they used in Tetwan. Sometime later, my wife answered a call from Eretz Yisrael from a fellow with a real Sephardi accented Hebrew thanking me for sending the Tetwan kesher. I assume the Yerushalmi went to the Tetwan shul in Yerushalayim to check it out, and the people there realized the kesher they use is not the original Tetwan kesher. The fellow who called was probably one of them, calling to say how happy they were that I had helped them recover what they had lost.”

That kind of call is what makes it all worth it for Rabbi Schneid, whose sole agenda, Reb Yehoshua Yankelewitz says, is spreading knowledge of Hashem’s mitzvos.

“He would come down to the summer camp I ran in Monsey free of charge to give hands-on demonstrations about batim, about giddin, on how to make ink. He’s a very warm, goodhearted person and he has taught safrus so many people for free. If you’re ready to learn, he’s ready to teach. And the quality of what he has to impart is simply peerless.”

In Pursuit of Truth

A cheerful sort whose mischievous smile never seems to leaves his face, Rabbi Schneid may seem like an unlikely warrior. But a happy warrior he is, intent on defending time-honored practices of generations past. When, many years ago, an organization with a stated mission to raise safrus standards began declaring a commonly occurring lettering in many people’s tefillin to be invalid even bedieved, Rabbi Schneid felt it was time to act.

The issue involved what’s known in halachah as the “kutzo shel yud,” the small extension descending down from the yud, the smallest letter in the alef-beis. This safrus advocacy group pronounced any tefillin without such a protrusion on the letter’s left side to be pasul, even though in Europe this had been considered unnecessary based on a responsum of the Chasam Sofer. The Gemara gives the example of the kotz, or thorn, of the yud as an example of something tiny whose absence disqualifies a sefer Torah, and Rashi and Tosafos argue over the Gemara’s intent. Rashi says the kotz is the foot of the yud on the right, while Rabbeinu Tam disagrees, seeming to say there’s a thin line descending from the left as well.

But the Chasam Sofer says Tosafos’s intent is that so long as the left corner is squared off and a kotz descends from the right, that’s sufficient. Along came others who claimed that the Chasam Sofer, too, requires at the very least an extending point jutting out of the left side. In response, Rabbi Schneid argued that that’s not how the Chasam Sofer was understood in Europe, and that many sifrei Torah we have from there prove it. He sent the sh’eilah once to Rav Moshe Feinstein, who wrote a teshuvah (Igros Moshe Orach Chayim 5:2) agreeing with the lenient ruling that tefillin are kosher even without a kotz on the left, only to have a rumor circulate that the teshuvah had been forged — except that Rabbi Schneid has the original copy of the teshuvah.

Invalid, or just Unfamiliar?

Undertaking to closely study every sefer Torah he could get hold of, learning from old-style European sofrim and seeing a multiplicity of stam from diverse communities around the world, Reb Shmuel began to realize that there were entire styles (Velish, for example, which is similar to Sephardi ksav and was used in Lita) that had been lost to history.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 913)

Oops! We could not locate your form.