Who by Water?

| September 16, 2020We’re aching for what we had, pre-coronavirus, when we didn’t know how lucky we were

Rosh Hashanah, 2010

I’m in the guest bedroom of my daughter’s apartment in London. The glare of the clock in the darkness reads 4:02 a.m.

It’s “one of those days,” sorrow making its claim on my body — chest tight, head weighted.

“Let the year end with all its curses.” Eleven months ago, at the opening of this new year, our son, Yossi, drowned.

“Let the new year begin with all its blessings.” Ten days ago, as the year prepared to close, our daughter gave birth to a son and named him after Yossi.

The apartment feels too small for the bigness of today. I need to move, to think. I crouch by my suitcase, run my hands blindly over the folds of clothing, pull out a shirt and a skirt — can’t tell if they match — and scrabble under the bed for my shoes.

The hallway is quiet, which means the baby and his exhausted parents are asleep.

I open the front door and step out into the fresh air. The door clicks shut behind me, and that’s when I realize I don’t have the key.

The city of London is black. Even the glow of the streetlights is dulled by fog. I shiver. Not from cold.

A new year without Yossi.

What if I can’t go on without him?

What if I don’t want to?

I sit on the top of the small set of stairs and let the tears come. Eventually I get up and try the door handle. It doesn’t budge. The only way to get back into the apartment is to bang on the door and wake someone. Instead, I decide to go for a walk.

I wander in and out of the gnarled lanes near the apartment, then on to Brent Street — the main artery of the neighborhood. I pass fortressed storefronts and empty bus stops. For long blocks, I’m the only one outside.

I’d expected London to be cool in September, but my shirt is glued to my back, the air stiff as if awaiting its own sentence on judgment day.

A year ago, on Rosh Hashanah, at our shul in Los Angeles, my husband and Yossi said the words together: “Unesaneh Tokef … like sheep passing under the stick of the shepherd, one by one, counted and judged… who will live, and who will die… who by fire and who by water…”

Who by water. We said those words. Yossi said those words. Sang them. It’s such a stirring melody.

A year ago, I davened for clarity for the shidduch we were looking into for Yossi.

A few weeks after that, during Yossi’s first date, the girl stepped away for a minute and he called me, whispered, “Mommy, I think she’s the one,” and hung up. So we had clarity. We also had plans. For a wedding. For a life.

Then, on what I still call “that last Friday,” the phone rang, and my husband cried, “They can’t find Yossi. He’s in the water.” We rushed to the hospital.

My husband went in to see Yossi. He had to step around needles; they were all over the floor. Adrenaline. Because they tried, again and again, to save Yossi.

We buried him exactly six weeks before the day he was supposed to get married.

I’m walking uphill on the London streets. I stop to catch my breath near a stone wall: marbled greys and browns, with the freshness of green, stubborn through its fissures — mold and moss and rebirth.

Today, the gavel comes down on the world.

Who will live and who will die.

Last year, when Yossi sat with us and we ate honey and wished each other a good, sweet year, was it already written? The doctors telling us, “We did everything we could,” and, “We’re so sorry.” The hopeful syringes of adrenaline littering the floor. Was his fate already sealed?

Who at his predestined time and who before his time…

Yossi was only 23 years old. He loved to learn and to teach. He made so many people smile.

Who by water and who by fire, who by sword, who by beast, who by famine, who by thirst, who by storm, who by plague, who by strangulation, and who by stoning.

On one of my sleepless nights after Yossi died, I read that there are nine hundred and three ways to leave this world.

Today, we are supposed to ask our Father, our King for life.

For months after Yossi died, every morning, I’d wake up, and there’d be the tiniest sliver of time where I’d feel normal. Then came the remembering: Yossi died. Often the disbelief: Yossi died? Sometimes the rage: Yossi died!! Then: If Yossi died, how can I live?

Almost ten years since Yossi died.

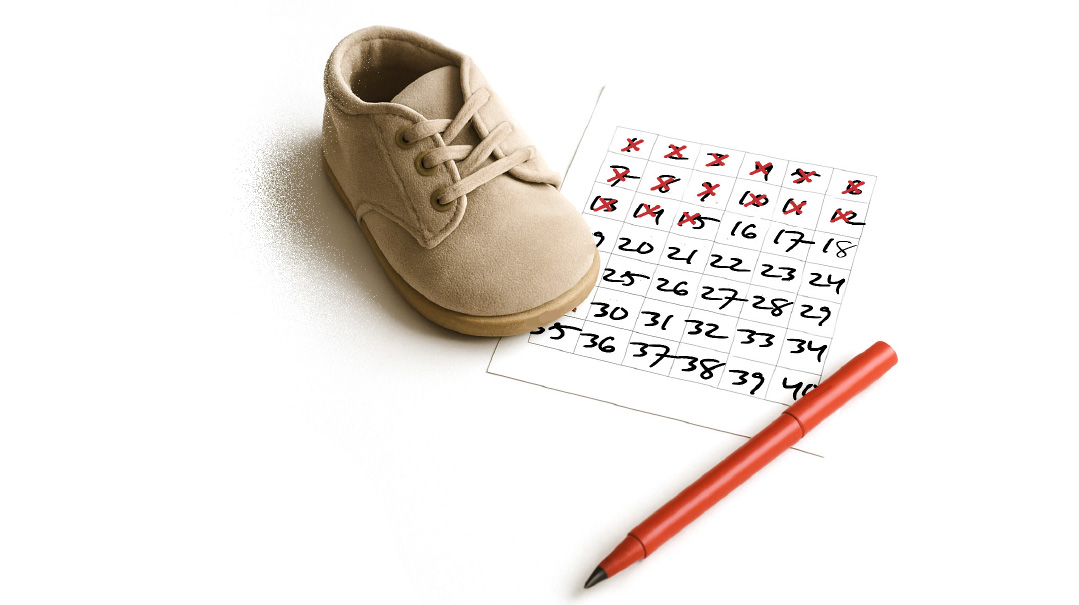

Some people measure their growth with pencil marks on a wall. I measure mine by each year’s Unesaneh Tokef.

In the past nine years I’ve choked on the words “Who by water,” closed the machzor in tears, and, on one particularly difficult Rosh Hashanah, ran home in middle of davening because I couldn’t say the tefillah asking not to die.

As the years rolled forward, I managed to stay in shul, say all the words, even consider their meaning.

Unesaneh Tokef is not about the many ways not to die. It’s about the one way I can live: aware of the journey of the neshamah — my son’s and my own.

Yossi completed his world tasks. Me? I’m still here, which means I still have work to do.

Yossi died on Friday afternoon. When we got the call, we’d already set the table for Shabbos. We came home from the hospital, and there was Yossi’s place, his Kiddush cup, his setting, ready for him.

At that Shabbos meal, I couldn’t bear to see his empty chair, so I moved from my seat to his. In the blur of those first terrible moments, Hashem was showing me that, already, I knew what to do. I filled the space that was Yossi’s, so we could make it through that first Shabbos meal without him.

The pain rises and recedes; it never goes away. But living is about taking a step, just one step if that’s all I can manage, as long as it’s in the right direction.

This year, as we pass, one by one, under the stick of the Shepherd, we’ll daven to be spared from “the water and the fire and the sword and the beast and the famine and the thirst and the storm and the plague.” Especially the plague.

We’re aching for what we had, pre-coronavirus, when we didn’t know how lucky we were.

I was like that after Yossi died. For a long time, I wanted only to go back to my “before.”

This year, I’ll ask for life; I’ll ask that if I am allowed another day, another minute, I remember to see it as a gift and an obligation because “Who will live and who will die,” is in the hands of Hashem.

How we live? That’s on us.

(Originally featured in Family First, Issue 710)

Oops! We could not locate your form.