Who by Fire?

Revisiting the battlegrounds of the Yom Kippur War

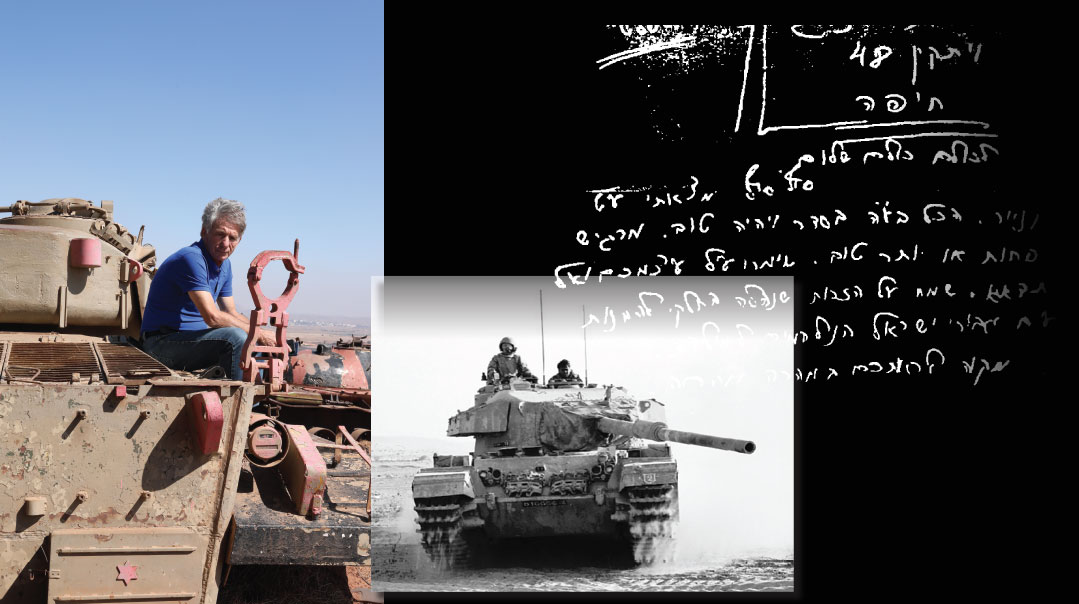

Photos: Menachem Kalish, Mishpacha archives

"Early on Yom Kippur afternoon, we felt that something was in the air, as one or two cars came to Kiryat Arba to collect some reservists. The atmosphere in the yeshivah turned electric, and the words ‘mi yichyeh, u’mi yamus’ gained new meaning.”

That was hesder yeshivah student Danny Steinberg’s first inkling that a disaster had befallen Israel’s complacent army. And that’s how he found himself on the way to the Suez Canal on Yom Kippur 1973, to fight back waves of Egyptian infantry and tanks whose advanced Soviet missiles were savaging Israel’s vaunted air and armored forces.

High over the Canal at about the same time in his Skyhawk fighter was Noach Hertz. Rushed into combat, he braved volleys of surface-to-air missiles in repeated bombing raids against Egyptian forces pushing into Israeli-held Sinai. But after days over the Suez Canal, his squadron was sent north, and his aging jet was shot down over Syria. Hertz entered the hell of captivity and torture and emerged a different person.

Far beneath those roaring jets on the Syrian front was 18-year-old tank loader Chaim Edri. He was one of a small number of Israeli armored forces who participated in a miracle on that Yom Kippur, as a tiny Israeli force held off over 1,000 Syrian tanks on the Golan Heights.

Forty-six years after the guns fell silent — and as threats from all sides of Israel’s borders once again grow urgent — I head out on a journey to revisit the battlefields and talk to these former soldiers. I find that many who experienced the shattering events of that war are reluctant to talk. But on my quest to tell the story, I discover that in its own tragic way, it was as miraculous as the euphoric victories of the Six Day War.

And for these soldiers–turned–bus drivers, businesspeople, and rabbis — all of them are defined by their trial of fire on that ultimate Yom Kippur.

Danny Steinberg

Role: Tank driver, Suez Canal, Egyptian front

“I had a feeling of trust in Hashem that He would help us in this milchemes mitzvah.”

“A few kilometers after El Arish, an officer stopped our tank convoy and told us to have our weapons ready because Egyptian commandos were operating in the area and climbing onto our tanks. That,” says Danny Steinberg “was the first of three moments in the war that I really felt fear.”

We’re sitting in Danny’s spacious apartment in Givat Ze’ev, a Jerusalem suburb with open vistas toward Ramot one way and Modiin the other. It’s a world away from the fear and fighting of the Sinai Desert, where as a young hesder yeshivah student, he served as a tank driver in General Avraham “Bren” Adan’s division. It’s hard to envision the calm man in front of me going through the violence he describes. The conversation supplements Danny’s diary, written while sitting in the protective steel walls of his “Shot” tank — an Israeli-modified version of the British Centurion — during lulls in the fighting. Amplified later in the long months spent surrounding Egyptian forces in “Africa” — the Israeli army’s name for the enemy bank of the Suez Canal — the diary provides a unique real-time view of the savage fighting of the Yom Kippur War.

Fresh out of basic training and back in Yeshivat Kiryat Arba that Yom Kippur morning, Krias HaTorah, not war, was uppermost in Danny’s mind. “They’d asked for a bochur to do Krias HaTorah on Yom Kippur, and I agreed,” he says. “I managed the kriah for Shacharis, but when Minchah came, I’d barely completed it when a truck screeched to a halt outside the yeshivah. A soldier called my name from the window, because I was responsible for getting my friends together in an emergency. ‘That’s it,’ I said to myself, ‘if they’re calling us — who have no combat experience — the situation must be desperate.’”

But it was singing, not panic, that surrounded the students as they left the yeshivah to the battlefront. Pausing only to gather tefillin and change out of rubber-soled shoes, the young men were accompanied by the singing of “ki lishuas’cha kivinu” as they left.

After a journey through Gush Ezion to pick up other soldiers, the bus arrived in Yerushalayim, where tallis-clad passersby called out their brachos and wiped away tears. The way south was crammed with trucks in a giant convoy, and as night came, the yeshivah students davened Maariv and made an emotional and heartfelt Havdalah. They broke their fast on some fruit that boys from the Gush had brought, and jokingly asked whether anyone still remembered how to start a tank or change its oil. But reminding them that a battle was on, jets streaked low overhead, afterburners flaring against the dark sky on their way northward.

“About two hours later, we arrived at the Shadma base, where hundreds of reservists of every age and type were milling around,” recalls Danny Steinberg. “We received uniforms and a personal kit — plus a juicy red apple from Uri, our platoon commander — and introduced ourselves to our tank.”

Working intensively, they loaded 72 shells for the main armament and thousands of 0.3 machine gun rounds, and mounted the massive tank on its transporter.

Three hours past midnight, the transformation was complete: the Shabbos-clad yeshivah students had been replaced by battle-dressed soldiers, moving out in a ponderous column of tank transporters. But in the chaos of the mass call-up, the crew’s gunner didn’t turn up, and Yossi Carmel, the tank’s loader, had to take his place. That meant that the loader’s spot had to be filled — and in the chaos of war, the only available person was a mechanic from the base. They were going into battle on the back foot.

As the day dawned, the feeling of detachment from the war ended abruptly as the officer at El Arish warned of marauding Egyptians.

“I began suspecting every palm tree — perhaps a commando was going to leap onto our tank when we weren’t looking” says Danny Steinberg. “I later heard that that happened a few times: Egyptians clambered onto the moving tank transporters and life-and-death fights broke out over the tanks at close quarters.”

It was close to nightfall on the day after Yom Kippur when the tanks were finally unloaded, and Danny’s platoon drew into defensive positions to pass the night, afraid of an Egyptian attack. But the night passed uneventfully, and by first light the untested soldiers moved out toward Baluza on the Sinai coastal road to engage the enemy.

“The terror of the Egyptian commandos had passed and going into action for the first time, my feeling was calm,” says Danny. “I had a sense that nothing would happen to me and a feeling of trust in Hashem that He would help us in this milchemes mitzvah.”

Moving through the sand dunes southwest of Baluza, they spotted enemy tanks and prepared to engage — but then something went wrong. “Israeli Skyhawks dove onto us, releasing their bombs. They all missed, but we were very shaken.”

Focused on the enemy armor in the distance, platoon commander Uri gave the order to fire when someone reported infantry approaching. Switching to the more immediate threat, someone shouted over the radio: “Don’t shoot, don’t shoot! They’re signaling with their hands!”

The Israelis held their fire as two figures approached and Danny suddenly realized what the white “surrender” cloth they were holding really was.

“Seeing the black lines, I realized that it was a tallis!” says Danny. “The two ran up and we saw that they were our soldiers. Their faces were blackened and they looked exhausted. They drank a lot of water, and then explained that they were part of a group of 22 soldiers who had escaped from a canal-side outpost and were sheltering between the dunes about two kilometers ahead.”

Danny’s tank was ordered to go on alone ahead while the rest of the force engaged the approaching Egyptian armor. Being alone for the first time in bandit country felt like a bad dream. “When we reached the group, the stranded soldiers reacted emotionally by surrounding the tank, touching it, and caressing the treads.” The parched soldiers drank and drank, and then all 24 climbed onto the outside of the metal beast for the six-kilometer journey to safety in the rear.

In my family, the story of the tallis is well-known, and is the reason that I had reached out to Danny (a cousin), but his diary provides a window into some of the most important clashes of the war.

Returning to the front, the lone tank discovered that the rest of the platoon was heavily engaged with Egyptian forces. “We destroyed one tank, and turned northwest to look for other targets, when Menachem, our tank commander shouted “Fire! Quickly! They’re shooting at us! Fire! Fire!”

As the driver, Danny couldn’t see what was happening, but he felt the tank shudder. “At first I thought nothing had happened, but then the new gunner called out, ‘The commander is hit!’ Later it turned out that a round had entered the tank’s turret, killing Menachem, our commander.

As Danny panicked, the gunner shouted out, half-panicked, “Back! To the right! Back! To the right,” as they left the kill zone.

Just how desperate the combat near the canal itself was became clear to them from the action overhead. “Phantom jet fighters flew over us westward with a deafening roar, and a few seconds later we heard the explosions of their bombs and the Egyptian anti-aircraft fire.” But they learned quickly that the Israeli Air Force’s advanced American-made planes were shockingly exposed to the Egyptians surface-to-air missile umbrella over the battlefield. “With the sound of the jets we looked up and saw the trails of the SAM missiles. Once I saw the astounding screen of Egyptian missiles that our planes had to evade, I understood why the air force’s losses were so high.”

Bloodied by their first encounter with combat, Danny’s tank went in search of first aid. They met a few half-tracks, which contained food, and also a medic who bandaged them. By late afternoon they were back in Baluza, where the Rabbanut took Menachem a”h, the commander who had fallen in the day’s fighting.

As darkness came, the Egyptians broke off contact as well. “That happened throughout the war,” says Danny. “It was as if there was an agreement between the two sides that fighting stops at dark.”

Shocked and disorientated by their brush with death, there was still a fortitude that came from faith. At the base, Danny suddenly saw IDF Chief Rabbi Shlomo Goren, who cut across to Danny, grasped his hand emotionally and said, “Say Hagomel with me.” In response, a loud “mi shegemalcha” erupted from the crowd around them, and a wave of emotion swept over Danny.

Those feelings of trust in Hashem were to remain throughout the deadly fighting near the Suez Canal. “I didn’t manage to daven with a minyan at all because we left too early each day and I spent 13 hours a day behind armor plating. But I managed to say the amidah in the driver’s seat — there was a real sense of ‘mi’maamakim,’ that Hashem would help.”

As I discover in weeks of interviews and conversation about the war, there are two types of people: those who will talk about their experiences, and have done so many times — and those who are too traumatized to talk at all. But from the yeshivah students, it’s clear that a strong element of faith was often decisive in their experience of war.

It was Tuesday, the third day of the Yom Kippur War, when Danny had his second major shock. Heading out to an area of low hills near the canal, his platoon dueled with Egyptian forces for an hour, and hit an enemy target.

But suddenly things changed. From the Egyptian lines they saw a mysterious red light coming toward them. It was platoon leader Uri who once again understood what it was. “Missile!” he cried out. Ordering his driver to reverse down the hill, the rocket missed.

This was the platoon’s first encounter with the Egyptians’ game-changing weapon — the Sagger. Until the Yom Kippur War, tanks had roamed the battlefield freely, concerned only by other tanks or powerful artillery. But the Sagger — a Soviet missile supplied to the Egyptians and Syrians in vast quantities — changed all that. Instead of fleeing from the charging tanks, the Israelis were shocked to find the Egyptian infantry standing their ground. The wire-guided weapons — called “suitcases” by the Israelis due to their luggage-like stands — stunned the IDF.

“We weren’t prepared for the Saggers, and as a driver we tried to find ways to deal with them, like zigzagging,” recalls Danny. “Unlike the Six Day War, when the Arab armies collapsed, this time they knew how to fight. The fact that they were able to cross the canal — our Maginot Line — was remarkable. The high command scorned the Arabs’ fighting abilities, but in the field we saw that they were at least equal to us.”

That first encounter with the Saggers nearly claimed the lives of the platoon leader’s tank crew. Uri’s tank was hit by a missile, and although the crew escaped, Steinberg received the heart-stopping instruction to rescue the crippled tank. As dusk came, and with Israeli tanks on a ridge to the east, he drove onto the battlefield at high speed, under the guns of the Egyptians. With an artillery barrage descending, they hitched the disabled vehicle to their own tank, and dragged it, agonizingly slowly, back to Israeli lines.

After days of combat, the crews were exhausted, sometimes falling asleep while driving. In one incident, Danny’s tank commander dozed in his turret, and only woke up when he heard the sound of a truck, impaled on the tank’s gun and dragged up the road.

Yom Kippur quickly gave way to Succos, which they celebrated Thursday night among the armored vehicles. “I was thinking of my parents in Haifa going to shul,” says Danny “and I decided to make Kiddush for everyone. We all forgot our exhaustion and made Kiddush on matzah in absence of wine.” Even secular soldiers gathered round for Kiddush.

Wine there may not have been, but there was food. I laugh at Danny’s description of his unit receiving large quantities of gefilte fish — amusing given that era’s pride in the “new Jew,” the fighting, tanned Israeli soldier whose military prowess was now being fueled by shtetl fare.

There on the battlefield, the Rabbanut didn’t manage to bring arba minim, but the hesder students made time to daven together. And they received a visit from the brass who wanted to congratulate the yeshivah boys, then a novelty in the Israeli army.

Sitting in the brigade commander’s truck — the only place with light to read — they heard knocks on the door. It was the brigadier himself together with his senior officers. The soldiers stood up for him, but he said, “Sit — I have to stand for you. You are heroes of Israel.” Turning to his deputy, he said, “These are yeshivah students. In Israel, they only know how to shout at them — but in this war they’ll learn what they are. This is our youth, and if only the whole army could be like them.”

In the Israeli army of that era, it was an exceptional admission on behalf of the officer. “We stood there dumbfounded.”

Crossing the Suez Canal looms large in the Israeli memory of the Yom Kippur War, and it’s to Danny that I turn to understand how much the average soldier understood of that in real time.

“Since Shabbos, a week after the war began, we realized that something dramatic was going to happen, and the IDF was going to go on the offensive,” explains Danny. “We knew that we had to cross the Suez Canal, firstly in order to encircle the Egyptians, but also as a counterweight to the ground that they had seized on our bank.”

But to get to the canal, they had to pass the “Chinese Farm,” as it became known to the Israelis. An agricultural research station that used Japanese equipment, the unfamiliar script on the machinery gave rise to its name. The place was to become infamous as the site of a fearsome battle, where the paratrooper brigade and armored corps sustained horrific losses from the Saggers and machine guns of the entrenched Egyptian troops.

On that Tuesday, they headed toward the Chinese Farm, about five kilometers east of the Suez Canal, and immediately a large tank battle began. But then the situation spun out of control: Tens of Saggers were fired at the Israeli force, and the tank drivers began zigzagging, all the time keeping track of the deadly red lights that showed a missile in flight.

Over the radio, the brigade commander urged them to storm the farm, but to Danny’s relief the platoon leader decided to withdraw beyond Sagger range. In retrospect, says Danny, “I thank Hashem for giving Uri the wisdom not to attack. I don’t want to think what would have happened if our small force had attacked the place.”

After days of defensive battle, Danny’s platoon got a chance to inflict some sweet revenge on the Egyptians. A force of Russian-made T-62 tanks ventured out of their umbrella of surface-to-air (SAM) and Sagger missiles around the canal, and moved northward.

“From six kilometers away we engaged them and picked off tens of tanks. They didn’t fire back, and as we got low on shells, we worried that they were drawing us into a trap. Only afterward we found out that the T-62’s gun isn’t accurate beyond 2.5 kilometers.”

But destroying enemy armor couldn’t break the Egyptians’ hold on Israeli territory — crossing the Suez Canal was the only way to do that. And then on Simchas Torah, Danny had the chance to make that happen.

“We went back to repair our tank’s electrical system, which had become damaged, and waiting for the mechanics to get to us, we fell asleep at the side of the road. An officer noticed that a tank was sitting inactive,” says Danny “and shouted at us, ‘Why are you sleeping? Does your tank not drive?!’ We told him it could drive, but not shoot. ‘Then start dragging the bridge!’ he shouted. ‘You’re the only tank available to drag the roller bridge so that Arik [Ariel Sharon] can cross the canal.’

“Without being able to shoot, we were essentially a tractor going into a war zone,” says Danny Steinberg. “But we found the bridge next to the road and waited for instructions on how to tow it.”

A week into the war, the abandoned bridge — key to Israel’s war effort — illustrates the chaos that the army still faced.

The young soldier eventually crossed the Suez Canal and spent months in the desert with the Israeli army encircling the Egyptians, who were forced to negotiate, as their water supplies were now dependent on Israel.

But at this point, Danny’s diary ends; the second half of the manuscript was stolen after the war, and the rest was completed from memory 30 years later.

For Danny Steinberg, the diary’s title summarizes what he took from his Yom Kippur War ordeal: Ki Chilatzta Nafshi Mimaves. “Hashem spared me — and it gave my life different priorities.”

When the Rabbinate Was Called to Action

“Two hours before war broke out, I was the chazzan at Musaf for about 100 soldiers,” recalls Rav Yisrael Ariel, a rabbi on the northern front for the IDF during the Yom Kippur War. “When I reached Keser I expected to hear a large response from the minyan — but instead there was silence. The hall was empty.

“I went out and found the soldiers gathered around [battalion commander] Avigdor Kahalani, who was standing on a tank. I jumped up and asked him why he hadn’t let [the soldiers] finish davening. That’s when he told me that war was going to break out in two hours and we needed those tanks up on the front line immediately.”

Apart from offering support to soldiers and bereaved families, the IDF rabbinate suddenly had to contend with providing chazzanim for far-flung military bases. “Unfortunately, some of [the chazzanim] were captured on the Hermon and tortured; we found others who’d been tied up and executed by the Syrians,” recalls Rav Ariel. “It’s a terrible feeling to have sent soldiers to be chazzanim who met that fate.”

As the war extended into Succos, the mass call-up of reservists also required the rabbinate to supply arba minim. “We suddenly needed lulav and esrog for 100,000 soldiers in the north,” Rav Ariel says. “So I picked up the phone to Bnei Brak to someone called Yitzchak Meir, who ran to the shelters to find the Ludmir arba minim suppliers. By that evening they’d loaded a thousand sets in two trucks.”

The arrival of the arba minim boosted morale. “I stood at the base for two hours with the arba minim,” says Rav Ariel “and soldiers, religious and secular, begged me to let them shake it. I saw how at a time of hardship Jews love mitzvos.”

But the rabbanut’s job didn’t end just with religious services. A thousand Jewish soldiers died on the Golan Heights, and Rav Ariel created a chevra kaddisha of 250 people to comb the enormous battleground for dead bodies. In the end, all of those missing were brought to kever Yisrael.

In a remarkable twist, Rav Ariel says that the rabbanut also buried the Syrian war dead. “The Syrians lost 4,000 soldiers on the Golan,” he says, “and I asked for volunteers to bury them. Not one person stepped forward — it’s a terrible job. And for enemies? But I suggested that in Yechezkel, the Navi says that Gog will be given a burial place in Eretz Yisrael ’near the sea.’ The Targum says that is a reference to ‘Yam Ginosar’; in other words, next to the Kinneret.”

Only one person, Yossi Vinograd, stepped forward, and Rav Ariel says he performed a tremendous kiddush Hashem. “He buried 800 Syrians on their territory, which we held for a few months. The Syrians only asked for 400 back — it seems they were Assad’s family — but the media came from all over the world to see how Jews treat even their enemies.”

NOACH HERTZ

Role: Skyhawk fighter pilot, Syrian front

“The war taught me that nothing happens on its own. If you look closely at a situation, you’ll find that Hashem is behind it all.”

“Today I understand that I survived by a miracle,” says Noach Hertz. “On the fifth day of the war I was sent to fly over the Golan, and over Khan Arnabeh in Syria, there was suddenly an explosion — my plane had been hit in the side. I blacked out and woke up to find myself spiraling toward the ground. I ejected and the next thing that I remember, I woke up in a Syrian hospital with my leg amputated.”

The setting of our interview — the Hertzes’ modest moshav home in Yesodot, a pastoral chareidi village between Yerushalayim and Ashdod — is dissonant. Only the tractors digging up the road outside cover the lowing of the cows in the distance. The desperation of the Yom Kippur War seems far away from Rabbi Hertz’s tranquil, patriarchal face, and his seforim-lined dining room.

Noach Hertz’s story has been retold many times, but I’ve still chosen to go and meet him. Meeting one of the air force’s golden boys, whose shattering experiences of Yom Kippur transformed his life, adds another dimension to understanding what happened in those fateful days.

“I was born in 1947 in Ashkelon to secular but very philosophically minded parents,” says Noach Hertz. “Perhaps coming from thinking people, it enabled me to react to the Yom Kippur War to turn to Hashem.”

In 1968 he graduated as an engineer, and was then drafted into the air force. He qualified on the Skyhawk, an aging American fighter that had been superseded by the far-more-powerful Phantoms entering service with the IDF.

“In 1967, when I was still a student, there was the tremendous victory of the Six Day War. There had been a great fear in Israel of a churban. People fled the country, but then the Israeli Air Force executed a surprise attack and wiped out the enemy air forces in hours.”

“That,” says Noach Hertz, “led to a feeling of kochi v’otzem yadi, and total scorn of the Arabs’ capacities. That feeling was soaked into the atmosphere of the IDF then. Bases were unready; there was no proper intelligence. Egypt and Syria wanted to get back their pride, but the high command was arrogant — they never dreamed that someone would challenge us.”

It was only on Shabbos — Yom Kippur morning — that the high command finally understood that war was a few hours away. Tragically, it could even then have turned out very differently if the air force had been allowed to carry out its plans. “At 10 a.m., the air force was ready to carry out a surprise attack on the missile batteries like in the Six Day War.” But at the last minute, the operation was canceled and Israel lost the initiative.

Hertz was not involved in those opening moves, having been demobilized just before the war broke out, and living on a southern kibbutz with his wife and young child. But he was rushed back into the cockpit and the next day found himself flying bombing runs over the Suez Canal into a storm of missiles.

Equipped with no electronic countermeasures to outfox the missiles — unlike the modern Phantom — Hertz’s Skyhawk had to fly below radar level to avoid being shot down.

Just as the Saggers wreaked havoc on the tanks, the planes fell like flies to the SAMs. Nearly a third of Israel’s air force was downed in the opening few days of the war. There was no overall control between different air force bases, and it was only on Tuesday that Hertz understood the disaster that had unfolded. “That day I attacked the Chinese Farm [a week before Danny Steinberg narrowly evaded the Saggers there], and had to dodge a SAM-6 missile. But when my commander, Shelach, was killed over the Suez Canal, I understood that this was total war.”

It was Thursday, and Succos, when life changed for Noach Hertz forever on the Syrian front. “The plan was to attack from Quneitra to protect our tanks, and the intelligence briefing said that there were no more SAMs. It turned out that the Syrians had received more overnight, and the Golan Heights was full of missiles. That morning,” recalls Hertz, “five Skyhawks were downed because they had attacked from above radar level, but we still went ahead with a high-level attack.”

“Human beings have a defense mechanism that enables them to focus in these situations, and so I thought, It can’t happen to me. We were flying at tremendous speed, but suddenly there was a tremendous boom — I didn’t see the missile hit — and I woke up to find that I had a few seconds left before hitting the ground. It’s clear Hashgachah pratis that I woke at all, because I blacked out immediately again.”

Noach Hertz stops and raps his leg. It makes a hollow sound in his dining room, and explains his pronounced limp. He woke to find himself a POW in a Syrian hospital, and an amputee. Captivity is not something he wants to discuss, but it was brutal. After three days, he was transferred to Al-Mazeh prison in Damascus with no painkillers and no doctor — “It was a miracle that I didn’t get gangrene,” he says.

Hertz was also tortured there. In other interviews he has spoken of the electric shocks, beatings, and hammer blows to the nails that the Syrians inflicted. But to me he just says drily, “There was no Geneva Convention.” Under the torture, other pilots died, and Hertz wonders whether the fact that he wasn’t a Phantom pilot meant that the Syrians went easier on him.

Kept in solitary confinement for months, questions of Jewish identity and meaning gnawed at him. A guard — an Arab Israeli who had moved to Syria — taunted him that Israel had stolen Arab land. Noach Hertz was consumed with why, in fact, the guard was wrong. Sheer loneliness and suffering in the freezing prison led him to think of Judaism and to determine to explore it if he ever made it out.

That happened at the cease-fire on the 11th of Sivan, after an eight-month captivity. A career officer, Hertz flew helicopters and did a desk job after his release until 1985, but the process that had begun in Al-Mazeh prison bore fruit in 1982.

“The crisis of the Yom Kippur War triggered two things: a movement of young people to leave Israel, and the teshuvah movement,” he says. “Only then did I have the courage to act on what I believed and become chareidi.”

Forty-six years later, Noach Hertz has told his Yom Kippur story many times, but there is nothing formulaic about his words as he ends our interview: “The war taught me that nothing happens on its own. If you look closely at a situation, you’ll find that Hashem is behind it all.”

It’s that utter conviction that rings in my ears as I head north to the site of Israel’s life-or-death struggle with the Syrians.

CHAIM EDRI

Role: Tank loader, Syrian front

“The way that your handful of tanks stopped those massive Syrian forces is a story that should be known more widely. It’s a miracle. You could thank Hashem for what happened in this place.”

Even at the end of a scorching summer, the Galil is lush with vineyards and fields. But just across the Arik Bridge over the Jordan, the scenery changes abruptly. The verdant hills give way to cornflower yellow, studded with olive-green scrub and mounds of black volcanic rock. Here in the Golan Heights, the signs of war are everywhere: Skull-and-crossbones signs mark old minefields; soldiers patrol in camouflaged jeeps; a convoy of Merkava tanks rumbles its way to another exercise.

Driving north shortly after Rosh Hashanah, I’m here to see these behemoths’ rusting forebears, and hear the story of perhaps the greatest miracle of the Yom Kippur War — how for three fateful days on the Golan Heights, a handful of Israeli tanks held off Syrian forces ten times their number, and saved northern Israel.

“For us the war started right here under these trees,” says my guide and former tankist Chaim Edri. Now a trim 65, his sun-leathered skin tells of a life spent on the windswept Golan. But as an 18-year-old tank loader fresh out of basic training on that Yom Kippur, he had no inkling that war was coming until Syrian bombs started raining down around him.

“We were camped across the road from Nafakh, the main Israeli base of the Golan, when Sukhoi jets attacked us,” he recalls as we drive past. “They missed, but then artillery shells started to fall on that hill and we knew that this was war. We weren’t ready. Our tanks were old — mine didn’t even have working batteries. The Syrians had night vision equipment, so they could see us, while we couldn’t see them. And we had about 170 tanks against their 1,400.”

The thought of battle — facing an enemy who would shoot back — terrified the teenager. Chewing asphalt, the Israeli tanks drove the short distance to one of the most terrifying battles in history. “Emek Habacha” — the Valley of Tears, as the place is hauntingly known. Even today, there’s a menacing feeling about the area. In the distance is Quneitra, a Syrian ghost town abandoned since the Six Day War. Standing sentinel over the minefields between Israel and Syria are a few burnt-out tanks. A strong wind blows on the exposed outcrop.

“When we arrived, this whole valley was filled with Syrian tanks, hundreds of them,” explains Chaim Edri, clambering on top of a rusty Centurion tank. “They chose this valley because it’s flat. It’s the best place on the border to send in large forces, and their plan was to conquer the Heights and head down to Tzfat, Teveria, and northern Israel. We had about 40 tanks, commanded by Avigdor Kahalani, and we had to hold them all off without artillery or air support.”

The place we’re standing on is a ramp, one of a number of artificial plateaus built by the Israelis to provide firing positions over the border area. Tanks would drive onto the ramp, fire, and then make way for the next in line.

For a number of hours on Yom Kippur, this strategy worked, whittling down the oncoming Syrians by expert tank gunnery. The Israelis discovered that the Soviet-made tanks had weak points. “Unlike our tanks, where the commander stood in the turret with a panoramic view of the battle, the Syrians only had a limited side view from their tanks. So we learned to hit the front and rear tanks in a convoy, while they were trying to work out where we were firing from.”

But soon, the sheer numbers of the Syrian forces enabled them to press forward and threaten to breach the Israeli line. “Syrian tanks started to come between these two ramps,” says Edri, “and the ranges went from a kilometer to 50 meters.”

“In tank training, you are taught that the minimum firing range is 900 meters, so that the explosive charge can open properly. But at these ranges, there is no aiming; like Western gunslingers, whoever draws first, wins.”

As the battle of Emek Habacha intensified, Edri’s tank was hit three times, and he mentally prepared to die. The first time the enemy round buried itself in a storage compartment, the second went into the tracks. But the third was a direct hit.

“It happened when the Syrian tanks came so close that to hit them we had to expose our tank on the forward slope of the ramp,” says Edri, gesturing to the turret of the tank we’re standing on.

“I was young, curious, and desperate to see what was happening outside, so I loaded a shell and just before we fired, I glanced out of the tank’s periscope. There was a blinding flash from an enemy tank gun, and then all went black,” recalls Edri. “Later it turned out that our tank had been hit next to its gun, where the armor is extremely thick. But the round knocked us unconscious and until today, I am partially deaf as a result.”

The battle of Emek Habacha lasted for three days of almost constant fighting. “We didn’t sleep at all, and ate biscuits and whatever we could get our hands on. A Syrian tank that made its way onto Avigdor Kahalani’s position was only discovered when it didn’t obey radio instructions to turn its lights off.”

“At one point we were trapped on our ramp with only three shells, as a force of 15 Syrian tanks approached,” remembers Edri. “We wouldn’t even have been able to scratch them if we’d fired, so we turned off our engine and lights and hoped they wouldn’t notice us. They thought we’d been knocked out, and they left us alone.”

Air battles of the type that claimed Noach Hertz’s Skyhawk were a daily spectacle for the tank crews. “At some stage I saw an Israeli Phantom jet pursued by two Syrian MiGs toward that mountain,” say Edri, pointing to a nearby slope. “The Israeli pilot dove toward the mountain, and at the last second he pulled sharply up — and the Syrians crashed straight into it.”

But in the desperate fighting happening elsewhere on the Golan Heights, there was no air and artillery support to spare. Edri discovered that the Israeli tanks were on their own.

We’re standing in the shade of a memorial to Edri’s fallen friends. In front are one Israeli and one Syrian tank, their barrels touching like two fencers with interlocking swords.

“I should have been dead here at 18, instead of my friend David Edri,” says Chaim. “He transferred to another tank that was hit, and then he was shot when he jumped out on the same side as the Syrians.”

It’s just after Rosh Hashanah, and I remind him of the words of Unesaneh Tokef. “Who by fire, who will live and who will die — you all passed through fire. The way that your handful of tanks stopped those massive Syrian forces is a story that should be known more widely. It’s a miracle. You could thank Hashem for what happened in this place.”

“I should say Gomel,” he agrees.

“The Jewish People have always been ‘rabbim b’yad me’atim,’ says Edri. It’s as deep as he’s willing to go in talking about his war experiences.

Perhaps it’s not surprising. The battles for Emek Habacha were horrific, and this is his emotional defense. “I saw a tank commander sliced clean in half by an enemy shell. Even today, if I smell something burning, I’m back reliving the scenes within a second,’ he says. “We all aged ten years in three weeks. If I didn’t block those memories out, I wouldn’t be able to cope.”

Although Edri is holding down the hatch on those traumatic memories, he shares his story with many groups of schoolchildren and soldiers. And as I act as interpreter, he shares the short version with a jeepload of hulking UN observers with blue berets and Fijian Army shoulder patches who drive up to see what we’re doing.

On the drive down to Katzrin, the Golan’s only town and longtime home to the Edri family, Chaim says simply, “I didn’t realize it at the time, but we saved the country. If our 40 tanks hadn’t been sent a few days before the war from Sinai to the Golan Heights, the Syrians would have crossed the Bnot Yaakov bridge over the Jordan River and into the Galil.”

As the car takes me down to that bridge and into Israel’s heartlands — traveling the opposite way to the route taken by Noach Hertz and Chaim Edri — the “Gemar chatimah tovah” on the radio reminds me that Israel is once again approaching Yom Kippur and Succos.

In what’s become an annual tradition, Israeli radio stations will once again broadcast the recordings of the soldiers trapped on the Suez Canal and pilots desperately trying to evade the missiles. The stories of the yeshivah students making Kiddush on top of their tanks, and learning Gemara in “Africa” will also be retold.

But only the men who experienced their own passage of fire, and their personal succah of Divine protection, can understand the true meaning of the Yom Kippur War. —

A Short History of the Yom Kippur War

The Yom Kippur War, which broke out on October 6, 1973, began with a massive surprise attack by Egyptian and Syrian forces on Israeli positions stationed at the Suez Canal and on the Golan Heights. Israel had occupied both locations as a result of the 1967 Six Day War.

The war was the result of an Israeli intelligence failure born of an arrogant underestimation of the Arabs’ military capacity — a hubris that took root with the humiliation of the Arab armies in the Six Day War. But the mass Israeli casualties — about 2,800 dead and 8,000 wounded — shook the country’s confidence and led to a reevaluation of military greater preparedness.

The war began when 32,000 Egyptian troops crossed the Suez Canal on Yom Kippur afternoon and quickly overcame the fortifications along the so-called Bar-Lev Line, taking many of the soldiers in the garrisons prisoner. When Israel’s armored forces counterattacked, they were repulsed by Egyptian infantry equipped with the new Sagger anti-tank missiles. Sheltered under the umbrella of Soviet-supplied surface-to-air missiles, the Egyptian beachhead was protected from Israeli air attack. By the next day, Egypt had taken control of a five-kilometer-deep strip along the length of the Israeli side of the Suez Canal.

The Syrian onslaught on the Golan Heights on Yom Kippur was similarly massive, with thrusts on two axes in the north and south Golan, and an airborne landing on the Israeli intelligence post atop Mount Hermon. Only 170 Israeli tanks opposed Syrian armored forces numbering upward of 1,400, and despite heroic Israeli resistance, Syrian forces broke through into the southern Golan. In the Quneitra Gap, or Emek Habacha, the Syrians were repelled.

By the third day of the war in the north, Israeli forces counterattacked, taking a large swath of Syrian territory and shelling the outskirts of Damascus. In Suez, Gen. Ariel Sharon put forces across the canal on October 15, in the gap between two Egyptian armies.

On October 23 a cease-fire came into effect, with the IDF encircling two Egyptian armies, only 100 kilometers from Cairo. Israeli troops stayed on the west bank of the canal until February 1974, but it wasn’t until May that they withdrew from inside Syria.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 781)

Oops! We could not locate your form.