What’s Behind Nechama Kichel’s Angst?

It’s strips like these that solidify The Kichels as frum social commentary at its finest

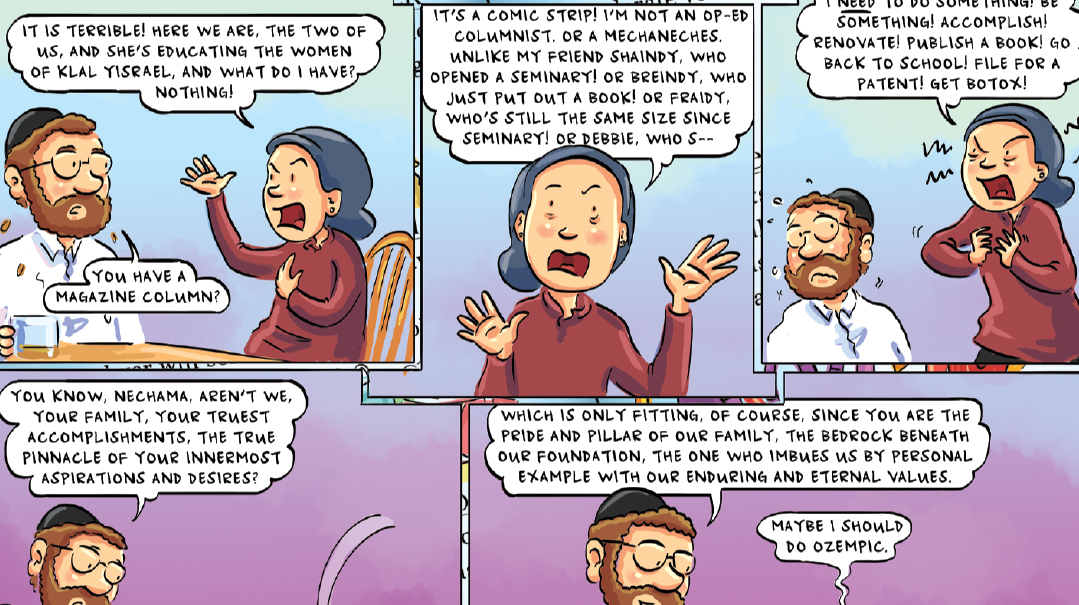

AS a frum mother and wife who is also an op-ed columnist — unlike Nechama Kichel, who only has a comic strip — I felt compelled to respond to The Kichels strip in which Nechama, hysterical and angsty, recounts to her husband Yechiel the significant accomplishments of her friends while she has nothing. When Yechiel reminds her that she has a magazine column, she responds: “It’s a comic strip! I’m not an op-ed columnist, or a mechaneches, unlike my friend Shaindy, who opened a seminary! Or Breindy, who just put out a book! Or Fraidy, who’s still the same size since seminary! I need to do something! Be something! Accomplish! Renovate! Publish a book! Go back to school! File for a patent! Get Botox!”

Yechiel tries to assuage Nechama by reminding her that her family is her truest accomplishment and reflection of her innermost aspirations and that she is the pillar of the family. Yechiel’s pep talk doesn’t work. Dejected, Nechama wonders if she should do Ozempic.

Bracha Stein and Chani Judowitz, the layers are deep. It’s strips like these that solidify The Kichels as frum social commentary at its finest.

This strip addresses various messages and attitudes frum women receive, intentionally or not, about their roles and expectations. Let’s begin with self-fulfillment via the family unit. A mother’s greatest accomplishment is her family. Yechiel even suggests that the family is the pinnacle of a woman’s aspirations and desires. Yet none of these ideas are comforting to Nechama, even though she herself likely believes them.

Nechama is a stay-at-home mom singularly devoted to fulfilling the needs of her family. In the examples she gives of women doing more than her, she’s not pointing out women who own businesses or have secular careers. She mentions the women doing klal work: the mechaneches, the chinuch expert, the op-ed columnist, the author, the seminary head. These are women who are “changing the world” and contributing to Klal Yisrael, while ostensibly also being fulfilled mothers and wives.

And this puts pressure on Nechama that she’s doing nothing. Why can’t she be fulfilled knowing that she is the pride and pillar of her family, that her family is her greatest accomplishment? Why is that not enough for Nechama? Is she digging for some sort of spiritual fulfillment?

And finally, why does Nechama wonder out loud if Ozempic is the answer to her woes? In the mix of friends who are doing impressive Jewish communal work, Nechama incongruously mentions Fraidy, who is still the same size since seminary. Is Ozempic really the answer to achieving the status and success Nechama seeks?

So what exactly is the broader social commentary behind Nechama’s saga? That stay-at-home mothers are dissatisfied? That the messages about self-fulfillment through home and family don’t work anymore? That women are feeling pressured to do more and more to make a difference outside their homes?

Whatever Bracha and Chani’s intention was (the beauty of art is that its interpretation lies in the beholder), I believe the core issue raised in this strip is that of self-actualization. Abraham Maslow, the creator of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, defined self-actualization as “self-fulfillment, namely the tendency for him [the individual] to become actualized in what he is potentially. This tendency might be phrased as the desire to become more and more what one is, to become everything that one is capable of becoming.” In fact, Maslow believed that self-actualization, the highest level of psychological development, rarely occurs and is only seen in less than one percent of the adult population. He called this the psychopathy of normality, that most of us, most of the time, function on the level lower than self-actualization.

Nonetheless, so many of us, like Nechama, have a deep desire to do more, to be more. We feel that we have potential that has not yet been fully tapped, and we’re either striving or waiting for the next big thing in our lives. We don’t want our talents and abilities to go to waste.

Self-fulfillment for frum women is highly personal. It is influenced by factors such as upbringing, chinuch, religious outlook, personality, and emotional makeup, to name a few. For many women, a family-centric, home-centered life without additional outside responsibilities is truly the pinnacle of their aspirations and desires. Homemaking and full-time motherhood are satisfying and more than enough — as they also utilize creativity, talents and strengths. For others, working outside the home provides a different and additional outlet for self-expression and self-actualization. And in today’s economic climate, many frum women don’t have a choice, whether they’re breadwinners supporting a husband in kollel or working due to the increasing need for dual incomes.

Self-actualization is also impacted by stage of life. Nechama no longer has little ones at home, but she’s very busy managing the needs of her children, ranging from bar mitzvah bochur to marrieds. If Nechama represents the average stay-at-home, middle-aged mom, the strip suggests she is experiencing a mid-life crisis, that what worked for her up until now no longer works, and that she needs some sort of external self-validation and fulfillment. Truthfully, Nechama doesn’t want to open the next seminary or pitch an op-ed column. She complains that she needs to do something, but I’m convinced she’s less driven by a desire for self-actualization than by an uncomfortable feeling of inferiority.

In a sense, Nechama realizes she can’t change the world, but she can change herself. The low-hanging fruit is the perceived easy route to weight loss, as changing oneself is often very external.

While we’ll never know if Nechama is expressing latent spiritual aspirations or if she’s just feeling less-than, what she really needs is a way to fill her tank. Frum women are perpetual givers, carrying various loads to maintain their homes and the emotional and physical needs of their families. While that may be inherently fulfilling for many, women still need meaningful chizuk, outlets, and connection.

Nechama might benefit from getting a job (part-time works!) or train in a field that suits her interests. While joining the workforce is not a prerequisite for self-actualization, work can add another layer of personal fulfillment to our lives. Exploring interests through hobbies, passion projects, and volunteer work also helps. But there still needs to be a level of self-awareness of one’s unique strengths and abilities in selecting suitable work or areas of interest, and not to just do what everyone else is doing.

If Nechama weren’t a comical character, I’d introduce her to Aliza Bulow, founder of Core Torah. Core offers “circles” of support to strengthen relationships and ignite passion and purpose among women in local communities, networking those circles both regionally and internationally. Nechama would benefit from joining a Core Circle, a micro-community of women who get together regularly to nurture meaningful relationships.

“Mothers today need more attention and support and are getting less. There’s more work to be done, more demands on our time, and the social fabric of our lives is fraying,” Aliza said in a Family First interview three years ago. “Women report having less and less time to nurture the friendships that have the power to sustain and fulfill them.”

The most important thing is that whatever we do to fill our tanks, whatever attempt we make at self-actualization, we stay in our lane. We stop looking around at what others are doing. We stop feeling pressured to do what’s trending. We have the confidence to do what we need to do to, based on our unique makeup and circumstances. Comparing ourselves to others stifles self-actualization. This is particularly challenging since we live in close-knit communities, and as we admire our friends and neighbors, we are more prone to compare ourselves to them. Yet comparison inevitably results in feelings of inferiority, distracting us from acknowledging or even discovering our own gifts and abilities.

Dear reader, you may think I’ve lost my mind analyzing the motives and actions of a cartoon character. But I quote Bracha Stein in an interview I did with her and Chani Judowitz on the podcast I co-host with Rivki Silver, Deep Meaningful Conversations (DMC): “Humor is a great tool for making points. It softens the edges and makes people more receptive. Humor is also such a valuable tool in helping you get through life. When you’re able to find humor and laugh, it’s very empowering and gives you the tools to tackle your challenges in a serious way as well.”

Nechama’s angst may have hit some readers in a real way. Seeing our experiences reflected in the faces of cartoons can have a surprisingly cathartic effect. If nothing else, it gives us a moment’s pause to self-reflect and laugh at our idiosyncrasies. Maybe we’ll even be more receptive to change and grow.

Alexandra Fleksher is an educator, columnist, co-host of the Deep Meaningful Conversations podcast, and creative director of Faces of Orthodoxy, an initiative of the Orthodox Union. Alexandra lives in University Heights, Ohio, with her family.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1019)

Oops! We could not locate your form.