The Things That Count

I n my hometown of Atlanta during the month of February a pall akin to mourning hovered like a dark cloud over the heads of millions of sport fans. Their beloved football team had suffered a bitter loss in the most important game of the year the Super Bowl. The fans are still inconsolable. A palpable grief envelops the bereaved sports community each of whom feels a personal loss as they review the game recalling its every play. In an effort to find some comfort they revisit the high points of the full season the impossible catches the precision passing the powerful offense and defense. Although reliving the year’s highlights seems to restore their spirits in a way it only deepens the fact that their team had clutched defeat from the jaws of victory. Their only consolation is “wait till next year.”

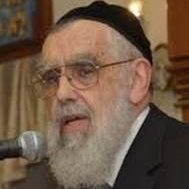

In Jerusalem during the same period of time a pall of mourning also hovered like a dark cloud over the heads of tens of thousands of Torah scholars. Their beloved rebbi and master Rav Moshe Shapiro had gone to his eternal reward. So great was his impact that over 50 000 people young and old attended his funeral. Rav Moshe was a superb teacher a world-class Torah scholar unparalleled in this generation brilliant of mind and generous of heart with encyclopedic knowledge and profound understanding of the entire corpus of Torah with both Talmuds and all of halachic and Jewish philosophic literature at his fingertips blessed with the rare ability to articulate and transmit what he knew. His bereft disciples feel orphaned; they are inconsolable. They replay recordings of his shiurim review notes of his lectures try to reexperience the powerful intellect that shared its wisdom with them.

Although reviewing his insights seems to restore their spirits in a way it only deepens the bitterness of what they have lost. Their only consolation is that their teacher is in the Olam Ha’emes communing with the souls of the great teachers of our past.

These two sets of grief bring to mind the declaration we traditionally recite when completing a Talmudic tractate. Thanking G-d for having given us the Torah we say “…anu ratzim v’heim ratzim — we run and they run….” The recitation contrasts the pursuit of Torah and eternal life as opposed to the pursuit of things that have no substance. That is to say just as there is running and there is running so also there is mourning and there is mourning.

Those who mourn the loss of the big game: what makes them sad? Their civic pride was injured they lost some validation through their personal identification with the team. Before millions of viewers they could have been recognized as winners of the Super Bowl and now they are known as losers.

Those who mourn for Rav Moshe ztz”l: what makes them sad? They lost not just a great teacher but primarily an inspiring figure who engaged their minds and hearts a mentor who was an indispensable guide on the avenue to higher things. They echoed the rabbinic lament in Bava Basra 91a: “Woe to the ship that has lost its pilot.”

None of this is meant to demean in any way those who are sports fans (Es chata’ai ani mazkir hayom — I confess that I still follow the vicissitudes of my old hometown teams.) Fans are good and decent people who are entitled to relieve the stresses of daily life by watching physical excellence and discipline on the field. They (we) are happy with wins unhappy with losses. But in the final analysis the ineluctable fact is that certain things matter and certain things do not. In practical terms what upsets us and what does not upset us what make us sad and what does not — as well as what gives us joy and what does not — is a measure of who we really are.

There is mourning and there is mourning. There is running and there is running. There is laughter and there are tears. Whatever life has in store for us — and may the joys override the grief — if there must be weeping let it be over something worthwhile.

Oops! We could not locate your form.