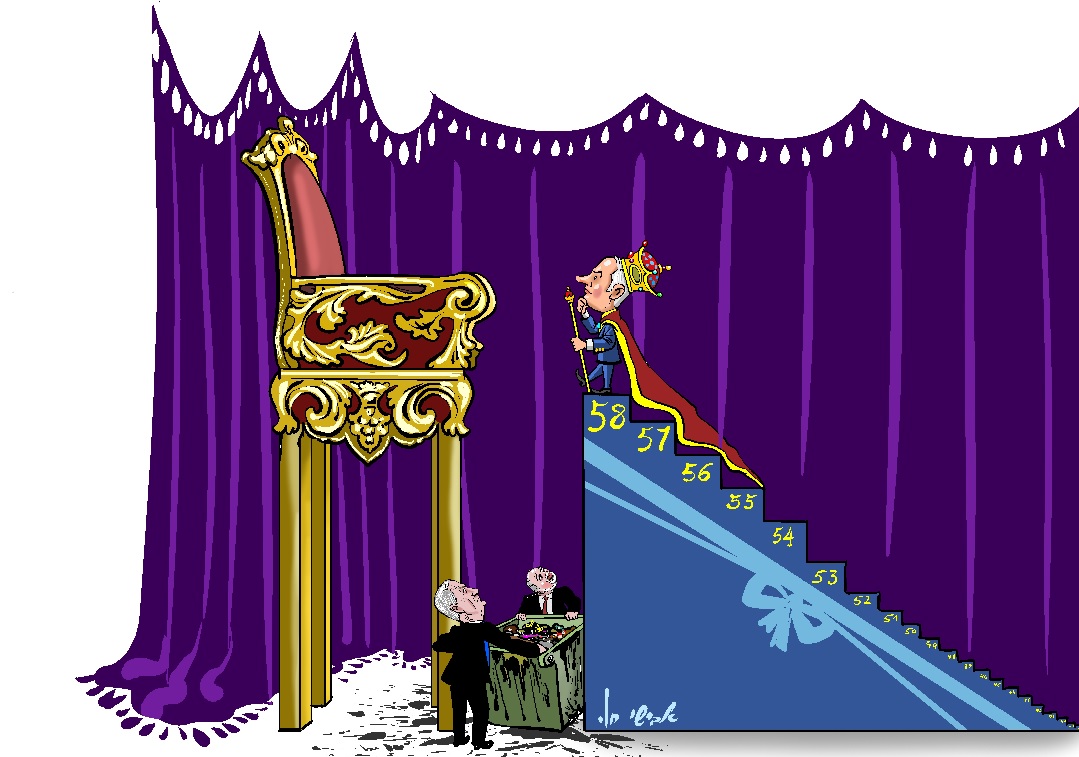

Ups and Downs

I

n all, UTJ garnered 267,890 valid votes as of 8:53 on Wednesday.

In many chareidi cities, there was a steady rise for UTJ. For example, in the first elections of 2019, UTJ in Modiin Illit garnered 18,008 votes; for the second election, that number rose to 18,606 and this week, there were 18,926 UTJ votes. That is a total rise of 5% (compared to a 13% growth for Shas).

The numbers are a bit different in Beitar Illit. In the first elections of 2019, UTJ received 12,532 votes, followed by 13,431 and in the third election got to 13,588 — an impressive 8% rise from the first time. But there was only a minor rise between the first and the second.

Likewise in Tzfas: the first election saw UTJ receiving 2,007 votes, followed by 2,317 (310 more) in the second, and this time, 2,656 — a total growth of 649 votes (32%). Incidentally, the city did not disappoint for Shas either, as it grew by 842 votes, or 41% between the first and the last election.

In Beit Shemesh, UTJ got first 13,506, followed by 15,031, and finally, 15,447. That is a total rise of 1,941 votes (14%). This figure is somewhat overshadowed however, by Shas’s rise in the city by 2,039 votes, or 32%.

At the same time, there are other cities that did not follow the trend of growth in the chareidi sector. In Ashdod, the first elections garnered 13,606 votes for UTJ; the next one earned 13,627 (21 more) votes, and this week, there were 13,731, a mere 125 votes more than a year ago. According to Education Ministry figures for the high schools, the new crop of chareidi Ashkenazi 18-year-olds numbers nearly 1,000 people.

The picture was even more dismal in Jerusalem. While in the first election of 2019, UTJ got 60,632 votes, followed by 64,937 (a rise of more than 4,000 in half a year), this week, it only reached 63,313 — a decrease of 1,624 votes. Add to that the natural growth of the population that should have been manifested at the ballot box, we find thousands of missing votes —which either migrated to other parties or were not utilized at all.

Did Shas take these votes? In some cases, the differences make it evident that there was a migration of votes from one party to the other (protest votes by communities that do not feel represented enough in UTJ transferred their votes to another chareidi party). If we measure the change in percentage points from a year ago, we find that in Ashdod, Shas grew 28%; in Jerusalem, 25%; in Beit Shemesh, 32%. These are impressive growth rates. Meanwhile, UTJ grew 1% in Ashdod, 4% in Jerusalem, and 14% in Beit Shemesh.

What about Chabad, which votes for the “most chareidi party”? The secretary of Chabad Rabbanim, Rav Yaroslovsky, declared on Election Day morning that it was up to the chassidim to choose between UTJ and Shas. Deputy Minister Porush and his aide, Shneur Rosen, were in charge of the Chabad votes for UTJ. But while UTJ seemed to have successfully maintained its gains in Chabad, it was not a full partner in the votes that poured off from Otzmah Yehudit to other parties. Shas was the primary beneficiary, and in Beitar Illit, for example, Otzmah Yehudit voters (seemingly) moved primarily to Shas; only a few voted for UTJ. In Kfar Chabad, this trend is even more obvious: Out of 1,000 Otzmah voters in the last round, only about 50 voted for UTJ this time.

We will leave the calls for introspection and to learn the lessons of the elections to the publicists.

(Mishpacha.com)

Oops! We could not locate your form.