Unsustainable: the Conversation Continues

“Unsustainable,” about the pressures of materialism and shifting definitions of “normal,” resonated deeply with our readers

A Different Model› Rabbi Avrohom Weinrib, Congregation Zichron Eliezer, Cincinnati, OH

That is very real for many families and deserves the serious attention it is receiving.

I wanted to add an observation from out-of-town communities such as Cincinnati, where the day-to-day reality around these issues is noticeably different, not because people here are immune to desire or aspiration, but because the communal norms are almost the opposite of what is described in the article.

The differences show up in ordinary, almost unremarkable ways. A bar mitzvah is typically a Shabbos kiddush in shul, with sometimes a simple weekday seudah at home or in the shul for classmates. That is understood as complete. There is no sense that anything is missing. Children come, enjoy, and move on. Simchah is measured by warmth, not production.

Cars are chosen thoughtfully. It is common for people to ask guidance about what to buy, even when they could afford more. The question is often about fit and appropriateness, not image. One sees plenty of older cars, well-maintained, driven without apology. The parking lot does not silently announce who is “doing well.”

Homes are lived in for years without constant upgrades. Kitchens are not redone every few seasons. Additions occur when families grow and genuinely need more space, not because the neighborhood standard has quietly shifted. A home is perceived as a place to live and build a family, not as a statement.

Even celebrations and extras tend to stay within natural bounds. A vort, a sheva brachos, a kiddush — they are warm, dignified, and simple. People enjoy themselves without anyone trying to outdo the next simchah. The result is that joy feels shared rather than competitive.

None of this means that people never want nicer things, or that no one ever indulges. Those impulses exist everywhere. But in an environment where comparison is muted, those moments remain personal and temporary. They do not redefine what everyone else is supposed to do.

What emerges from this is something far more valuable than lifestyle convenience. When financial decisions are less charged, there is more menuchas hanefesh in the home. Shalom bayis benefits quietly but profoundly when money is not a constant source of tension or self-doubt.

There is also more emotional space for learning and growth. People have the bandwidth to be koveia itim, to take learning seriously, to think about ruchniyus goals without feeling they are falling behind in some other, unspoken race. When “normal” remains normal, spiritual aspirations do not have to compete with lifestyle expectations.

It’s not surprising that many families describe choosing out-of-town communities for precisely this reason. In conversations with couples who live here, the same themes emerge repeatedly, not as ideology, but as lived experience. It’s also striking that the overwhelming majority of our families chose to move here from larger cities.

While housing or logistics may be part of the explanation, what is often being described is a calmer inner life, a sense that one can live fully, raise a family, and grow without constantly measuring.

This is not a critique of other communities, nor a suggestion that challenges do not exist everywhere. It is simply an observation that in some communities, the unsustainable pressures described so powerfully in the article never come to shape the rhythm of life. Instead, a calmer set of values takes hold, one that allows families to live with greater menuchas hanefesh and to direct their energy toward what truly endures.

For those who are curious what this looks like in practice, the invitation is simple and sincere: Come spend a Shabbos with us. Sit in shul, walk the neighborhood, share a meal, watch how children play and how families gather. Taste a Shabbos that is unhurried, a community that is warm, and a way of living where joy is felt rather than performed. You may find that what feels sustainable on paper is even more meaningful when lived.

Thank you for raising an issue that matters so deeply, and for allowing room in the conversation to notice what is quietly working as well.

Call for Responsibility› Name Withheld

IN last week’s magazine, Shoshana Friedman once again hit it out of the park, framing the financial strain facing our community with clarity and balance.

As I read the rest of the issue’s treatment of financial pressure, I nodded along throughout. The editors assembled an impressive compendium, illuminating both the cultural forces driving unsustainable spending and offering a deep dive into how disciplined families manage to make the numbers work (and the calculated decisions required along the way).

And yet, I felt that something essential was left unsaid.

Yes, the standards are ridiculous. Yes, the pressure is real. But we also need the honesty to admit that, in many cases, we are not doing our hishtadlus. Too often, we are shirking responsible preparation for what Ari Stern aptly describes as the “war that’s coming.”

Rav Dr. Joseph Breuer addressed this directly in his essay “Vocation and Calling,” included in A Unique Perspective (Feldheim). He wrote that productive work alongside k’vius itim is neither a compromise nor a fallback, but an essential expression of a Torah life — a fulfillment of one’s duty to take his place in the world while living by Torah values and to meet the lofty obligation articulated in the kesubah.

Rav Breuer further cautioned that not every individual is suited to remain in full-time learning indefinitely, and that this path must be reserved for those truly called toward and equipped for it. He urged school officials and community leaders to exercise discernment in determining who may appropriately forgo practical vocational training, lest we confuse idealism with irresponsibility. Torah divorced from responsibility, preparation, and honest labor is not a higher ideal; it is a distortion that ultimately harms both the individual and the community (see Orach Chayim 156).

That distortion has real-world consequences, now visible in the unsustainable social pressures shaping our society. We need to be willing to talk about the infantilized young adults our system is producing — individuals shielded from responsibility, insulated from consequence, and rarely expected to develop resilience, initiative, or self-sufficiency.

This is not merely a personal failing; it is the predictable outcome of an environment in which parents quietly absorb costs and protect their children from the realities of life. The result is a culture where appearances and expectations spiral ever higher, with each family feeling compelled to match the next.

Too many people spend their childhoods and early years of marriage living comfortably, assuming that comfort and abundance will somehow continue indefinitely. They don’t realize, as Ari Stern put it so starkly, that “in order to survive, a frum family has to be in the top five percent of national income brackets.” Instead of learning to shoulder responsibility — financially or otherwise — they drift further into adulthood unready to earn, plan, or push back against unrealistic expectations.

The conversation about spending cannot be separated from the conversation about responsibility. As the issue noted, we are living in an “easy come, easy go” economy, where much of the runaway spending is driven either by the suddenly affluent or by parents feeling compelled to bankroll their children’s lifestyles. Very little of this reflects the true appetites or needs of the average person trying to live responsibly. If more people earned their own money and truly appreciated its value, there would be far greater care, restraint, and understanding about how it is spent.

I also appreciated the attention given to saving and long-term thinking. Disciplined saving and investing are among the few realistic tools families have to build stability. By way of personal example, as a teenager I picked up odd jobs and made a point of saving and investing roughly half of what I earned. Decades later, that still-untouched sum has grown quietly and significantly. Compounding works — but only if we teach our children early that saving and delayed gratification are virtues.

If we want to lower the temperature around money, we need more than takanos and cultural critique. We need to raise children who understand responsibility as a Torah value, who see parnassah as honorable, and who are equipped to stand on their own feet.

And one final observation, prompted by the discussion of wedding gifts. Gifts given to our children-in-law out of obligation — with a grimace, because “this is what society expects” — rather than out of genuine joy at welcoming them into the family, rarely bring simchah to anyone.

The article’s example of a family that gave a modest watch to a first son-in-law from a regular family and a far more expensive one to a second son-in-law from an affluent family illustrates the problem well: The gifts reflected circumstances rather than affection, and predictably invited comparison and resentment. While the offended party’s reaction reflected a troubling sense of entitlement and a lack of basic derech eretz, the underlying dynamic was entirely foreseeable.

Pointed Critique› Yehuda Haver, Lakewood, NJ

AMishpacha issue tackling a broad social trend from multiple perspectives is always exciting. However, I believe opening the section with the perspective of the anonymous “Rabbi A.” weakens the entire argument. In an age of sensationalized claims of crises, readers deserve to be respected with transparency. Real rabbanim and professionals are comfortable standing behind their strong statements, as the other quoted sources were. It is no surprise that the most harsh and accusing statements were coming from an anonymous source. Anonymity abuses the trust of a nation who respects daas Torah.

Another thing I’d like to take issue with is how much of the discussion focused on an issue relevant to only a small segment of the community. In the early 1230s, the Ramban corresponded with the Baalei HaTosafos regarding the banning of the Moreh Nevuchim. In one letter, he cautions them to avoid the instinct of assuming that a localized issue in one community reflects a global crisis. While Shoshana Friedman’s editorial correctly noted that systemic issues drive the affordability crisis for many, the main articles ignored this broader context and attributed an issue affecting a narrow “slice” of the community to many who can not fathom this struggle.

Finally, while both authors are correct that our communities mix economically, this has significant limits. Most in-town communities, where these issues are prevalent, are self-segregated into myriads of small “types,” each featuring its own nuances of hashkafah and lifestyle. Anyone living in town will easily point to the neighborhoods that face the challenge of social spending, while other neighborhoods cannot relate to this. Ultimately, choosing to live with the pressure of that lifestyle is a choice. These may be who the author calls “wannabes” (a crass term for a serious article), but it’s hardly about insecurity; it’s about a lifestyle choice.

The Gift of Simplicity› Anonymous

I was excited to see coverage about the topic of excess spending in frum society. However, one quote struck me the wrong way: “It’s fair to say that they [the gvirim] deserve to indulge a little bit. You can’t expect them to live as if they were earning a basic salary.”

Why not? Our generation has lost the ideal of simplicity. It’s all about dollars and cents. Can I afford or not afford? I believe that even if you can afford, a simpler lifestyle brings one closer to Hashem. There is only so much energy we have, and if we invest that into gashmiyus, by default we are not investing that into our ruchniyus.

Personally, I can afford to keep up with the Schwartzes, but I choose not to. I think I am doing my children a favor, rather than damaging them as some people believe. Just because I can afford a lavish lifestyle, who says they will be able to? Why should they limit the amount of time they are able to learn when they are married or need to work harder because they cannot live simply? By choosing to live below my means, I am providing them with the biggest gift of all: the ability to live simply.

Missing the Forest for the Trees› Name Withheld

I believe the reason spending has become so popular in our community lies in the sociological phenomenon of social closure — i.e., the community has grown so large that people are now looking for ways to distinguish themselves and exclude others from joining. I believes this lies at the root of the shidduch crisis and why we are less welcoming of baalei teshuvah than previous generations. Focusing on buying this car or that car is missing the forest for the trees. We need to be more tolerant of others. Whatever your spending is or isn’t, it’s assur to look down at others for what they do. Instead of focusing on takanos and awareness for how we spend, let’s start a campaign to not think yenem is a loser for driving a Chevy.

Missing Values› Etty Herschberg, North Woodmere, NY

IT was wonderful to see the topic of overspending on the front cover. I did feel though that the one point that was glaringly missing from both Shoshana Friedman’s article and the cover story was the concept of tzniyus. To say that our relationship with materialism tends to be murky disregards the very Jewish ideal of tzniyus.

In Sifsei Chaim, Rav Chaim Friedlander discusses the concept of tzniyus as a lifestyle to live by. We are not a people of Gucci and Prada. That is not a Torah value. To pretend that looking like “the daughter of a king” requires designer and super-expensive is to fool ourselves.

Yes, we should spend more to bring the kedushah of Shabbos and the kedushah of Yiddishe simchahs into our lives because it bring us closer to the Ribbono shel Olam, but a fancy car and fancy shoes certainly do not. Further, to forgive the “gvir” for overspending because he supports mosdos is to put our head in the sand. It’s time to stand up for Torah values, not Ferragamo belts.

Hurtful Portrayal› Someone working hard and struggling to afford the frum lifestyle without overspending, Edison, NJ

The article “A Trend We Can’t Afford” begins by correctly noting that the silent majority is financially choking. Unfortunately, it then veers into territory that is, for a large percentage of us, simply inaccurate and hurtful.

First, the premise that we are struggling because of indulgent or luxurious spending is untrue for most families. We are choking because the middle‑class squeeze is real and the frum lifestyle has become unaffordable. Yes, some people overspend — but to suggest that this is the primary or sole cause of widespread financial strain is simply incorrect. Even without a single luxury, the basic cost of living a frum life today is beyond the reach of many hardworking families.

But the article goes further, implying that making substantial money today is easy. One interviewee claims, “I sit with people all the time that are making $300,000 to $400,000.” That is not the reality for most of us. A large portion of our community works incredibly hard and earns far less. To portray high earnings as commonplace — or effortless — is not only misleading but deeply discouraging. If making that kind of money is truly “easy,” then by all means, please share the secret.

As someone who works in the real estate sector, I can say with confidence that the notion that “the average guy [can] buy a building with no money down and flip it for a large profit” is absurd and was never the case. Statements like these can make honest, hardworking people question what they’re doing wrong. Let me reassure my friends out there: You are doing nothing wrong. The article simply does not reflect reality.

True Strength› Anonymous

We’re blessed to live in a community rich in Torah, chesed and connection. At the same time, there’s often an unspoken expectation surrounding homes, renovations, simchahs, clothing and lifestyles. While no one may say it outright, the message can be felt clearly: Bigger is better, newer is preferable, and more is admirable.

I would like to suggest a different value system — one deeply rooted in Torah. Living within one’s means is not a compromise; it’s a strength. Paying one’s bills on time, avoiding debt, and making thoughtful financial choices bring peace of mind, shalom bayis and dignity. Chazal praise one who is sameiach b’chelko — content with what they have — not one who constantly reaches for what others display.

Not every family is meant to live in a large home or host lavish events. Some of us choose modesty not because we lack ambition or resources, but because we prioritize responsibility, stability, and gratitude. A smaller home that is owned, cared for, and filled with warmth can be far richer than a larger one fueled by pressure and debt.

May we continue to support one another in living authentically, responsibly, and with pride in the lives we are building — each according to our own means and circumstances.

Important Reminders› S.Z., Wesley Hills

There’s something almost ironic about reading an article titled “The Price of Belonging” while flipping past pages of glossy ads encouraging excess. But perhaps that contrast is exactly what made the piece resonate.

First, credit is due. It’s always meaningful when a frum publication chooses to shine a light on what may be the underlying challenge of our time, a values crisis that touches nearly every aspect of Yiddishkeit.

Second, I was struck by how naturally this article echoed a quieter voice many readers may have noticed in your pages: the Values Over Valuables comic. Through simple humor, it gently invites readers to slow down and live with values. For me, those comics felt like a small but timely nudge to take greater responsibility for my own spending and priorities. I’ve since found that intentional living is surprisingly contagious. There’s something deeply calming when people close their front doors and thoughtfully consider what they’re doing.

Finally, one thought I wished the article had explored further. While money and spending are the most visible expressions of the values struggle, there’s another, subtler fault line: the confusion between the outer expressions of ruchniyus and ruchniyus itself. Without intention in avodas Hashem, there’s a real risk that the lishmah never quite takes hold.

Pieces like “The Price of Belonging” and initiatives like Values Over Valuables serve as important reminders to turn inward and refocus on pnimiyus, so that both our gashmiyus and ruchniyus can be lived more honestly and healthfully. That is where real growth, and ultimately Geulah, begins.

Internal Insecurity› Lea Pavel

The coverage of the overspending issue repeatedly used the term “pressure,” but I personally do not find it an accurate one. “Pressure” connotes an external force. When someone decides to spend money or go into debt for a purchase or simchah, that is not because of pressure. The desire to follow the herd is internal, not external. Therefore, I’m not optimistic that an external campaign is going to be able to address an internal crisis, that of insecurity.

This so-called parenting principle of purchasing something for a child if the entire class has it as well? Parents are doing the same for themselves. We like to think that with adulthood we automatically gain the maturity to know what’s important in life, but this edition says otherwise: The high school Weltanschauung still has many a “grown-up” in its grip.

Frankly, no one is staying up at night wondering why you didn’t make an over-the-top bar mitzvah or didn’t get a luxury car. They’re up at night wondering how to pay for theirs. “Seven years of plenty, seven years of lean,” my CPA father oft quotes from the parshah. But we operate during the lean times as though we are still in the years of plenty, instead of adjusting accordingly.

I recall a letter from a few months ago where the writer was opining about a certain expensive standard that she “had” to pay for, yet concluded that she refuses to be the first one to buck the trend — someone else would have to.

With that mentality, nothing will change.

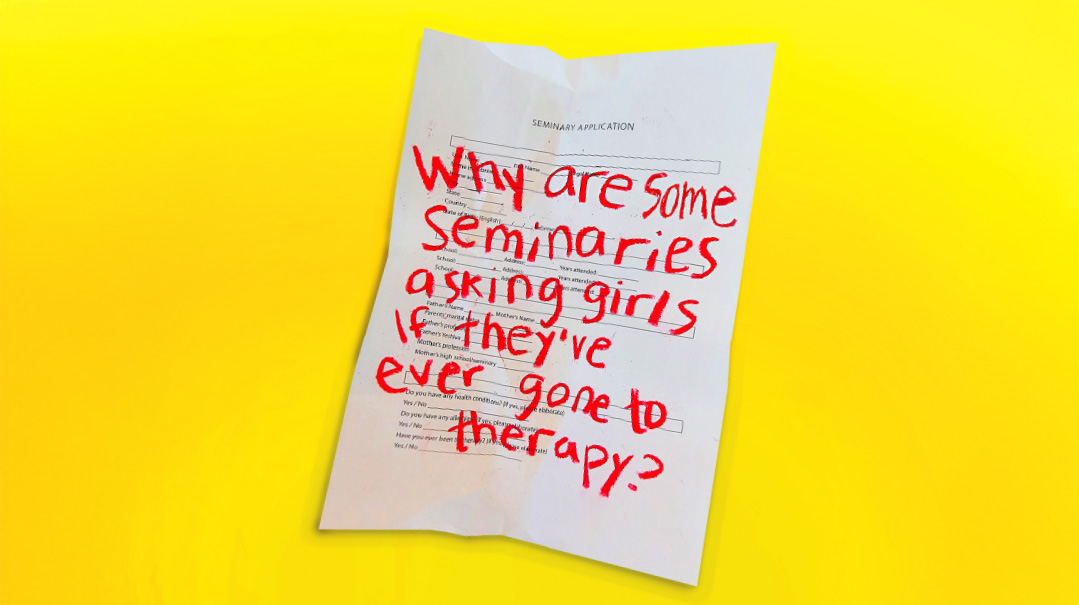

Proactive Measures› Shira R.

Thank you for raising awareness regarding the excessive spending in our communities. As I live out of town, many of the examples that were brought up are foreign to me. Simchahs are simple, homes are modest, and clothing is often purchased at the lower-end frum stores. But sending my children to camp and seminary brings this problem to the forefront. The guidance I receive is to give in, because “my kids can’t be the only ones without….” This is where I struggle. My values do not align with excessive and high-end clothing, shoes, coats, etc. even though, Baruch Hashem, I can afford them.

An idea suggested in the article that resonated with me was for each of us to tone it down in some way. When doing renovations or purchasing an item, there’s a commonly felt sentiment to just spend a little more, upgrade just one notch to make it better, fancier, more practical… But one person’s upgrade often becomes the new norm. The next person upgrades from there and things quickly get out of control.

Imagine if, instead, we decided to lower the standard by one notch. When asked if we want to upgrade the flowers, kitchen cabinets, coat, car, let’s really think about the ramifications of these decisions on our families and communities. It’s a real achrayus.

I’d also like to suggest that our schools and camps make rules regarding brand name items and designer watches. If our schools and camps limited or banned brand names on their premises, just like they do with technology, that would save families thousands of dollars and would tame the need for everyone to have the same expensive items.

Im yirtzeh Hashem, if we take steps to combat materialism, our gashmiyus will diminish and allow our ruchniyus to really flourish.

Barometer of Success› Name Withheld

I want to point out an important piece that was left out in the discussion about overspending. It’s not that we’re valuing money or gashmiyus more than Torah values; rather, we’re searching for happiness, fulfillment, and success.

We look at someone who made it in business, and we say, “Ah, he has it — success.” We were raised to strive to be successful, and that worth is tied to success. But while maybe children need that push to strive to become something great, as the Rambam writes, it’s time for us to grow up. Success is none of the above. Success is internal — doing the right thing at this very moment. I may barely be making ends meet, working a full day, coming home to help with the kids, and then squeezing in a few minutes to learn — but if I’m doing at each moment what Hashem wants from me, is there a greater success than that?

You might even be more successful than the talmid chacham who achieved his personal goals, while you sacrificed yourself the entire day for Hashem by simply doing what’s right.

If we can live this way and pass it on to our children, we won’t feel the need to chase after everything else. We’ll feel happy and successful just by who we are and what we already have.

Not the Norm› A.W.

The cover stories about overspending and the resulting social pressure were incredibly disturbing on so many levels. But I will limit my response to two points that I feel must be part of the conversation:

- What happened to tzniyus? The word was absent from your coverage. As we all know, tzniyus isn’t just about skirt (or sheitel) length. Yes, a wealthy family has every right to spend on luxuries, but some of the excesses described in the articles sounded downright grotesque. Referencing the overspending of the objectively wealthy, one rabbi was quoted as saying, “You can’t expect them to live as if they were earning a basic salary.” Correct, but why isn’t tzniyus part of the conversation?

- I live in a large out-of-town community where what you were describing is absolutely not the norm. People of different means live side by side, send their kids to school together, daven in the same shuls, and still make different kinds of simchahs. My children aren’t clamoring for expensive name brand clothing (some kids in their class have the fancy stuff and many don’t). The articles didn’t resonate with my reality.

But if the articles did resonate with you and your reality, know this: There are many other frum communities out there where you don’t have to suffer crushing social pressure. You can have friends/neighbors/shidduch suggestions who love you because you’re you, not because you impressed them with $34 hair bows or copied their vacation plans or upgraded to a late-model car. They’d rather you save the money or put it to better use. When making a shidduch, what we care about is not how impressive you look but your tochen, not your net worth but finding a life partner for our child.

What I’m trying to say is this: You don’t have to live this way! Move or find new friends. Normal frum people are out there.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1093)

Oops! We could not locate your form.