Turncoat

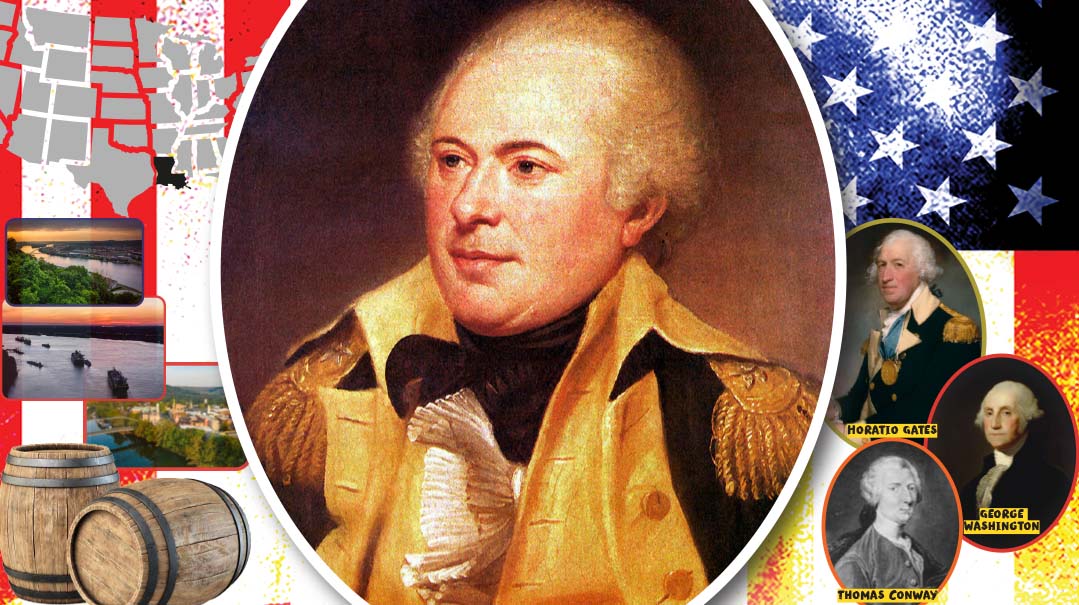

How General James Wilkinson betrayed George Washington — and got away with it

General James Wilkinson, war hero and friend to the Founding Fathers, was one of the most important men of his time. He was also the most notorious. It was an open secret that he was spying for the Spanish, and yet he was never convicted for his crimes.

How did Wilkinson gain the trust of the first five presidents of the United States, even when everyone knew that he was a traitor?

The Boy from the Manor House

1757–1775

James Wilkinson was born in 1757 in Calvert County, Maryland. The Wilkinsons were an important family — or at least they thought so. Grandpa Wilkinson had purchased a plantation in Maryland that he called Stoakley Manor. Although the family had money, they were not nearly as wealthy as Maryland’s elite. But from the way the Wilkinsons carried on about themselves, you’d never know that they were really simple planters (plantation owners). In their own eyes, they were just as important as those in the higher social class. They made over-the-top weddings, drove flashy carriages, and were always dressed in the height of fashion.

But their financial status was not as comfortable as they made it appear. When Grandpa Wilkinson died, he left boatloads of debt and some parts of the estate had to be sold to repay the creditors. But this did nothing to reduce the family’s importance in their own eyes. From when he was born, James was surrounded by people who were obsessed with money and status.

James was only six years old when his father became ill. Before he died, his father called him and spoke his very last words, “My son, if you ever put up with an insult, I will disinherit you.”

This was a lesson that James took with him for the rest of his life. He was known for blowing up in anger whenever someone insulted him. Ironically, he never inherited anything anyway. His father left everything to James’s older brother.

The sense of entitlement that James was raised with became a pattern in his life. When he came of age, he went to study medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. For two years, James dedicated himself to his studies. But then he became impatient and decided that he knew everything there was to know and that a third year of studies was unnecessary. Although he was not yet qualified as a doctor, he made plans to return to Maryland to practice medicine.

The War Hero

1775–1777

James’s career as a doctor wasn’t meant to be. In April 1775, just as James was about to leave Pennsylvania, news arrived that trouble was brewing in Massachusetts. Groups of colonists had started fighting with the British. The American Revolutionary War had begun.

Never one to miss an adventure, James joined the Continental Army. He quickly realized that war was not as glorious as he had naively imagined, but that didn’t stop him from becoming oddly obsessed with war — just like he was obsessed with money.

The army was the perfect place for James to feed his ego. George Washington himself was so dazzled by James that he promoted him to captain in a brand-new regiment, before he had ever fought in an actual battle. Not bad for an 18-year-old farm boy. And he didn’t remain a captain for very long — James turned on the charm and sweet-talked his way into the good graces of his superiors. He quickly gained the admiration of one general after the other, and used his newfound friendships to climb the ranks.

In 1777, after the Continental Army won an astounding victory at the Battle of Saratoga, General Horatio Gates sent James Wilkinson to the Continental Congress with official dispatches that told of the victory. Wilkinson stood before Congress and grandly told them all about the triumphs of Saratoga. Of course, he let them know just how big of a role his own heroics had played in the outcome of the battle. Congress was very impressed with James Wilkinson’s bravery. The congressmen completely ignored the fact that James had never led troops into battle, and promptly awarded him the rank of brigadier general. They even appointed him to the brand-new Board of War, which served as an intermediary between Congress and the army. Not bad for a 20-year-old.

Seeds of Doubt

1777–1778

It wasn’t all smooth sailing for the up-and-coming officer. Older and more experienced officers were shocked that young James Wilkinson had made it so far up the ranks. Then something happened that gave everyone their first inkling that Wilkinson had the makings of a traitor.

Nowadays, we tend to think of George Washington as someone who had the respect of all his men. That’s not entirely true. There were quite a number of generals and other important officers who had plenty of criticism for Washington. They kvetched to each other about his war tactics and wondered if they wouldn’t be better off having someone else as their leader. Brigadier General Thomas Conway led the pack of discontented officers, who together became known as the Conway Cabal, and he wanted to kick Washington out and replace him with General Horatio Gates as commander in chief of the Continental Army.

One evening, at a dinner with some of Washington’s closest men, Wilkinson made the mistake of having one drink too many. In his drunken ramblings, he let slip General Conway’s plans. His dinner companions immediately ratted on Conway and Gates to Washington. The scheming generals were furious with Wilkinson for betraying them. Of course, Wilkinson denied everything and blamed it all on another officer. But when Washington himself said that it was James Wilkinson who made Conway’s plans known, Wilkinson was forced to resign from military duty and the Board of War.

The Speculator

1784–1787

Crazy as it sounds, despite his clear betrayals of those close to him, people continued to be impressed by the charming James Wilkinson. After his resignation from the Continental Army, he joined the Pennsylvania militia where he was brigadier general. George Washington had learned nothing from the sorry saga of the Conway Cabal. Bizarrely, he personally requested that Wilkinson become a state assemblyman. All this power wasn’t enough for Wilkinson. He needed more: more power, more wealth.

In 1784, Wilkinson followed the path of many others seeking wealth and moved to the Virginia Frontier District of Kentucky (Kentucky gained its independence from Virginia and became a state in 1792). There were lots of opportunities in the vast lands of Kentucky, and Wilkinson tried his hand at selling merchandise and land speculation. Back in the early days of America, land was the most popular investment. Coming from overcrowded Europe, America’s huge swaths of dirt-cheap land was a dream come true for farmers who could finally own their land instead of renting from the poritz. Many people became wealthy overnight. Many others lost everything.

Wilkinson was in the latter group. He quickly acquired a tremendous amount of debt. He needed to make lots of money and fast.

1787

In 1787, Wilkinson made the trip to New Orleans, Louisiana.

Back then, this was like visiting an enemy country because Louisiana was in Spanish territory. The Spanish controlled most of America, while the United States pioneers were mostly stuck on the East Coast. However, the Americans were gradually spreading further westward, which the Spanish did not like at all.

King Carlos IV of Spain forbade anyone who wasn’t Spanish from trading on the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers. This was a problem for the American pioneers. The Frontier (as anything not on the East Coast was called back then) had a lot of entrepreneurs who were busy producing all sort of merchandise. But their customers were all on the East Coast or in Europe. One way to get their goods to the East Coast was schlepping it across the Appalachian Mountains. Well, that was never going to happen — not when there was a perfectly good river that could do the schlepping for them. So the merchants were forced to pay the Spanish an exorbitant fee to ship their merchandise on the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers. Wilkinson saw this law as a challenge and was determined to use it to his advantage.

When he arrived in New Orleans, Wilkinson invited the Spanish governor of Louisiana to dinner. (This time, Wilkinson remained sober.) He convinced the governor that it would be in Spain’s best interest to allow Kentucky to have a trading monopoly on the river.

“Interesting idea,” replied the Spanish governor as he downed some more wine. “What do I get out of this?”

Wilkinson promised that in return for trading rights, he would tell Spain all of America’s secrets — for a price. He sealed the deal by swearing an oath of allegiance to the king of Spain. The patriot had become the traitor!

Wilkinson needed a way to communicate with his new Spanish friends. He created a cypher code using English and Spanish. He called the code “Number 13.” The Spanish referred to James as “Agent 13.” As long as the code remained unbroken, no one could ever prove that it was James Wilkinson who was betraying the United States.

No one managed to break his code.

Close Call

1787–1804

Soon after his pact with the Spanish, Wilkinson once again became a high-ranking officer in the army. He had lots of juicy military secrets to sell. Despite his unbreakable code, Wilkinson lived in constant fear of being discovered. He knew that the punishment for treason was death by hanging. Ironically, his biggest problem was money. The Spanish paid Wilkinson for his information with Spanish dollar coins, which were hidden in barrels of coffee or rum. The barrels were shipped from Mexico to Louisiana, and then shipped up the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers to Wilkinson in Kentucky. Once, the Spanish crew members of the ship carrying the hidden coins figured out that the rum barrels contained much more than rum. They killed the courier, who was in charge of safeguarding the barrels until they reached Wilkinson.

The crew members were arrested and dragged before the local magistrate. They wasted no time trying to save their own skin by betraying James Wilkinson. But — the crew members only spoke Spanish! The court provided them with an interpreter, who proceeded to tell the magistrate that the men were murderous souls and plain greedy. He left out the part about Wilkinson. Turns out, the interpreter was also a Spanish spy!

Lewis and Clark

1804–1806

The famous expedition of Meriwether Lewis and William Clark was extremely important for the growing United States. In fact, the Lewis and Clark expedition is considered to be one of the most successful explorations of all time. In 1803, President Thomas Jefferson commissioned Lewis and Clark to explore the American West. For two years, between 1804 and 1806, Lewis and Clark mapped the geography of more than 8,000 miles across the country, made notes for potential settlements, and made peace with the 50 Native American tribes they encountered along the way. The expedition completely changed history for the United States. Now that the unfamiliar territories of the West were mapped, people could finally venture out there and establish new communities.

But the Lewis and Clark expedition almost didn’t happen.

In 1801, James Wilkinson had been appointed by President Jefferson to be no less than the commanding general of the United States Army . That didn’t stop him from spilling the beans about the expedition to the Spanish. He advised the Spanish to send people after Lewis and Clark to murder them! In return, Wilkinson was paid the princely sum of $12,000, about $225,000 in today’s money. Thankfully, the Spanish assassins couldn’t find the explorers, and the expedition was a success.

Court Martial

1805–1807

In 1805, Jefferson appointed Wilkinson as the first governor of Louisiana Territory. It was in this exalted position that Wilkinson plotted to harm the United States even more. He ganged up with former vice president Aaron Burr. Burr wanted to seize land in the north and create an independent country. Smelling an opportunity for more power, Wilkinson was all for it and was appointed the commander of Burr’s rebel army.

But Wilkinson felt let down by Burr. He thought that Burr was incompetent and would mess things up, and then they would all be caught. So, in true Wilkinson fashion, he informed President Jefferson of Burr’s traitorous plans.

In 1807, Burr was arrested and tried for treason. At the court martial (a court martial is a court for members of the military), it was discovered that Wilkinson had tampered with the evidence to remove suspicion from himself. Burr was acquitted and he fled to Europe in disgrace.

Jefferson removed Wilkinson from his position as territorial governor. Sensing his fall from grace, Wilkinson’s enemies were empowered.

Congress launched one investigation after the other. Everyone was suspicious of Wilkinson’s Spanish connections, and they were determined to prove the rumors once and for all.

But try as they might, no one could find any hard evidence of Wilkinson’s treason. There was even a newspaper in Kentucky, the Western World, which was dedicated to exposing Wilkinson as a spy. But despite everything, he was exonerated of every charge brought against him! Wilkinson was America’s most notorious spy, yet he never saw the inside of a prison cell.

Exposed!

Wilkinson was finally exposed as a traitor — many decades after his death in 1825. In the late 1800s, a cache of documents was discovered in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, that described the treason of an important Army official. It took years for historians to find the proof that Wilkinson was the traitor, and even longer for them to finally crack his Number 13 code.

In 1889, future president Theodore Roosevelt wrote about Wilkinson in his book The Winning of the West: “In all our history there is no more despicable character.”

Until today historians wonder: How is it that America’s greatest luminaries, from George Washington to James Madison, were taken in by Wilkinson’s charisma, turning a blind eye to the nation’s biggest traitor?

(Originally featured in Mishpacha Jr., Issue 897)

Oops! We could not locate your form.