Tunes of Redemption

A grandson's quest to trace Modzhitz composer Reb Azriel David Fastag

Photos: Mishpacha Archives

Many readers are familiar with the story of the beloved baal menagen of the Modzhitz court, Reb Azriel David Fastag Hy”d and the famous “Ani Maamin” death train to Treblinka. It was 1942, and tens of thousands of Jews were being shipped off daily to their deaths in cattle cars — to Auschwitz, Treblinka, Majdanek, and other death camps.

Inside one of those overcrowded, airless cars, where people were dying, crushed and standing, before the train even reached its destination, Reb Azriel David Fastag stood wrapped in his tallis, imagining himself on Yom Kippur standing next to his rebbe, Rebbe Shaul Yedidya Elazar Taub of Modzhitz, as he led the Rebbe’s davening in front of the chassidim. And then in his mind’s eye, he saw the words of the 12th Ani Maamin — "I believe with perfect faith in the coming of the Mashiach; and even though he may tarry, nevertheless, I wait each day for his coming.”

Closing his eyes, he thought, “Now, when everything seems lost, a Jew’s faith is put to the test.” And so he began to sing, first quietly, then stronger, and before he knew it, the entire cattle car was singing with him — broken and battered Jews on their way to their deaths, singing the song of eternal faith. Reb Azriel David opened his eyes to the sight of the singing train, and cried out, “I will give half of my portion in Olam Haba to whoever can bring my song to the Modzhitzer Rebbe!” He took out a scrap of paper and wrote down the notes.

The Rebbe, who had lived in Otvosk outside Warsaw, had chassidim throughout Poland, and one of them was Reb Azriel David Fastag, noted throughout Warsaw and beyond for his special voice and niggunim. Thousands would come to hear him and his brothers — his backup choir — on the Yamim Noraim, and his biggest admirer was the Rebbe himself: When a new niggun by Reb Azriel David reached the Rebbe, it was a veritable Yom Tov for him. In 1939, the Modzhitzer Rebbe’s chassidim managed to smuggle him out of Poland into Vilna, and from there he made his way across Russia to Shanghai and then to the shores of San Francisco, ultimately reaching New York in 1940, where he began to rebuild the chassidus. He himself was a gifted songwriter who created over 1,000 niggunim.

But would Reb Azriel David’s last niggun — the niggun of faith when G-d seems so hidden — ever get to his rebbe? Suddenly two young men shouted that yes, they would bring the niggun to the Rebbe at any cost. One of them climbed on the other’s shoulders, found a crack in the train’s roof, and then proceeded to jump. One was killed instantly from the fall, but the other survived, eventually making his way to Eretz Yisrael where the Rebbe’s son Rav Shmuel Eliyahu (the Imrei Eish) was living, and the notes were then mailed to Rebbe Shaul Yedidya Elazar in New York.

The notes arrived at the Modzhitzer beis medrash the day the Rebbe was making a bris for a grandson. The Rebbe was sitting next to the Kopyczynitzer Rebbe, Rav Yitzchak Hutner, and Reb Ben Zion Shenker, the only one of the group who could read musical notes. When Reb Ben Zion sang the niggun, the Rebbe exclaimed, “When they sang ‘Ani Maamin’ on the death train, the pillars of the world were shaking.”

Later, on Yom Kippur, the Rebbe sang Reb Azriel David’s “Ani Maamin” in front of his packed shul, when he famously said, “With this niggun, the Jewish People went to the gas chambers, and with this niggun the Jews will march to greet Mashiach.”

The story is familiar, but what most people don’t know is that while Reb Azriel David Fastag and his family met their deaths in Treblinka, one daughter survived — and today, her son is making sure his zeide’s legacy is not forgotten.

In Warsaw, Reb Azriel David Fastag was a fixture of the Modzhitzer shtibel on Nalewki Street, always surrounded by a throng of bochurim and young men. While Reb Azriel David lived simply, earning his livelihood from a small clothing store, his real joy came from the world of chassidic music.

“He composed dozens of niggunim before the war,” says his grandson Reb Aharon Zilbertzen, a Bnei Brak lawyer who’s made it his mission to dig up every available piece of information about his grandfather. “He was a real chassidishe mashpia, and had hundreds of followers — even Rav Yitzchak Hutner ztz”l would come to hear him in the shtibel as a bochur when he lived in Warsaw.”

For years, Zilbertzen has made a point of meeting every alte Modzhitzer he could find, to hear memories, even just snippets of information, about his zeide. “Twenty years ago, when I was living in Rechovot, I davened in a certain shul where I was the baal tefillah for Shacharis. I sang Keil Adon in the Modzhitz niggun, and after the davening I was approached by an elderly Jew, who introduced himself as Frishblatt. ‘Modzhitz, eh?’ he said to me. I said yes. He looked at me and suddenly asked if I had ever heard of Reb Azriel David Fastag.

“I wanted to hear more from him, so I pretended not to know. ‘Who was Reb Azriel David?’

“Ah,’ he answered, ‘Du bist a shvache Modzhitzer chassid — you’re a poor excuse of a Modzhitzer chassid.’

“To draw him out, I repeated the question, and after a few more derisive remarks about my ignorance, he told me, ‘We were two young Breslovers, 16 and 17, in Warsaw. Almost every Shabbos, we would go for Shalosh Seudos to Reb Azriel David at Nalewki. And you can’t imagine what was happening there.’ He described how people would cluster at the windows to hear from outside. Only then did I tell him that in fact, I’m his grandson — and he nearly fell over. He couldn’t contain his excitement. He had no idea that Reb Azriel David had left any zecher of himself, that anyone in his family even survived.”

The fact that one daughter survived is actually due to the instruction of the Imrei Emes of Gur. And this is how it happened:

Two mechutanim, Rav Abish Zilbertzen and Reb Azriel David Fastag, were standing on Nalewki Street between the Modzhitz shtibel and the Gerrer shtibel nearby, deep in discussion.

Rav Abish, whose son married Rav Azriel David’s daughter Baila Perel, was one of the most distinguished figures of the Gerrer chassidus in Warsaw, and the baal tokeia on the Yamim Noraim. But now a decision needed to be made about the young couple. The new husband, Yisrael Zilbertzen, had just returned from a “pilot trip” to Eretz Yisrael, where he intended to return with his wife.

But Rav Azriel David, hearing of the difficulties that would await the couple in the Holy Land, wanted to retract his permission for the move. In the end, they agreed to let the Gerrer Rebbe decide. And one word — the Imrei Emes’ clear and decisive answer, “Fuhr (go)!”— ensured that the daughter of Reb Azriel Fastag would preserve the line of a family whose every other branch was cut down in the war — most of them on that train to Treblinka.

Aaron Zilbertzen is the youngest son of Yisrael and Baila Perel. She passed away at the young age of 44, and Aharon was too young to hear about family history from his mother while she was alive. Even his older brothers had no idea who their illustrious grandfather really was.

But Aharon was thirsty for information, and even as a teenager, began collating every piece of evidence about Reb Azriel David that he could find. He pumped his father, and for that matter, every other person he met who came from Warsaw, about his maternal grandfather. He wandered in the circles of old chassidim, of Modzhitz and any other chassidus, who knew his grandfather or who had seen him on Shabbos or Yom Tov, at seudos and simchahs, who had drawn strength from his Torah, his emunah, and his song. And he traversed the country with a tape recorder, to record notes and tunes, incomplete or fragmented melodies, anything to preserve the memory of his grandfather.

“Before my mother died,” he says, “we were too young to ask or understand very much. We got fragments, though. We know she grew up in a house on Peinska St. 33 in Warsaw, and we know that every Shabbos night, ten to fifteen avreichim would come to be with our grandfather after the seudah, and they would sit until dawn, sharing divrei Torah and singing niggunim.”

As a composer to whom music was an elemental part of his soul, Rav Azriel David could always be seen humming some niggun to himself or swaying rhythmically to a tune in his head. While walking in the street, in the beis medrash, or during learning. Even customers who went to his store related that when he needed to weigh something for them on his scales, he would sometimes get so carried away in his humming as he arranged the scales, that he would forget where he was altogether, and begin drumming on the scales instead of weighing the objects.

All of Reb Azriel David’s children — Baila Perel’s siblings who all perished on the “Ani Maamin” train — were musically talented as well. Of her brothers Mordechai (Motel), Yechezkel (Chatzkel), and Shmuel Eliyahu, “Chatzkel was the most talented in singing and davening,” Zilbertzen says. “He also composed many of his own niggunim, which were lost in the Holocaust. My mother was the oldest sister, and among her sisters — Shulamis, Gittel, Chana, and Tzirel Hy”d, Gittel was the most musically talented. Her father recognized her talent and made her his critic. Before Yom Tov she would go over the songs he had composed, correcting and improving them as she went.”

Zilbertzen says his father couldn’t provide much more information, as he was a Gerrer chassid who davened in the other shtibel, and was only married for a short while before moving to Eretz Yisrael. “But he certainly remembered the Yom Tov davening led by his father-in-law, which took place in a large rented hall on Nalewki Street. Entrance tickets were sold to cover the costs, and anyone who wanted to participate in the davening had to pay. My father, who was there twice, estimated that some 1,500 to 2,000 men and women paid to attend the davening. The tickets first of all covered the cost of the rent, and if anything remained, they gave it to my grandfather, who always struggled financially.”

Yisrael Zilbertzen participated at least twice in the mass davening — once during the period when he was engaged to Reb Azriel David’s daughter, and then again after returning from Eretz Yisrael where he laid the groundwork for his family’s move. “My father was there once for Selichos and once on Rosh Hashanah. He also told me that that particular hall was usually divided into three shuls, but on the Yamim Noraim, the partitions came down to create one giant hall for Reb Azriel David’s davening. My zeide was a superb baal tefillah, but the truth is that his voice wasn’t so strong, so alongside him was the Modzhitz choir, made up of his brothers, another dozen adults, and a few children.”

But Yisrael Zilbertzen only remembered one melody of his father-in-law. “He knew Reb Azriel David’s niggun for ‘B’tzeis Yisrael’ — probably because it was sung repeatedly over Succos.”

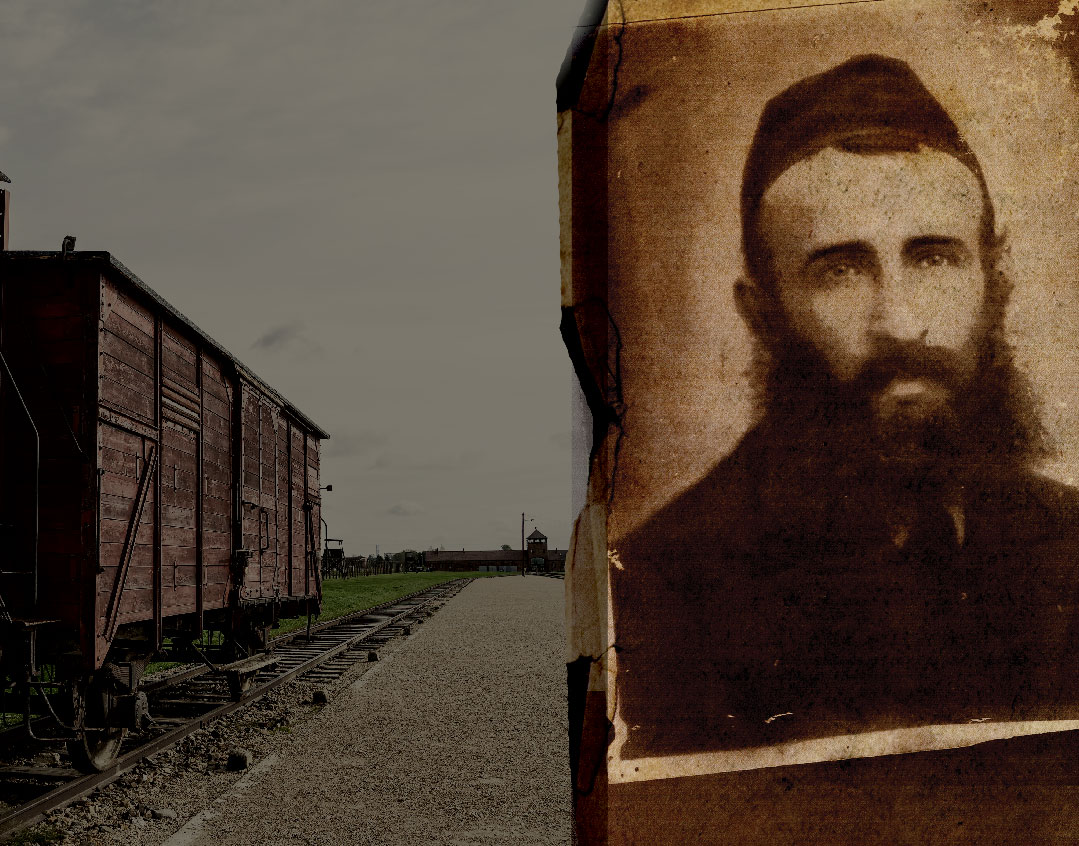

Aharon Zilbertzen displays an authentic entrance ticket for one of these events. “My mother brought it in her luggage, along with a passport picture of her father, when she moved to Eretz Yisrael. Honestly, we went through every drawer, file, cabinet, and envelope looking for any other picture or memento of our zeide, but didn’t find anything. Not even pictures of their wedding. The passport picture is the only one of him in existence that we know of.”

Reb Azriel David, a sincere and faithful chassid, had become somewhat of an idol for hundreds of young bochurim and avreichim who accompanied him to every holy gathering, and especially to his monthly Shabbos excursions to the Rebbe in Otvosk.

Reb Azriel David was always awarded a place near the Imrei Shaul for the seudos and the Rebbe would often honor him throughout the tish with various niggunim.

The sincerity of his davening became a byword in the community; as he went before the amud, his brow furrowed in concentration, his body shook with devotion and his voice rose gradually in intensity. “He was entirely focused on the siddur before him,” an elder chassid by the name of Binyamin Davidson told Reb Shlomo Avraham, official chronicler of the Modzhitz chassidus. “When I was a young child, my father took me to Shalosh Seudos in the Nalewki shtibel. I remember many long rows of tables, the men singing in perfect harmony along with Reb Azriel David until long after the stars came out.”

Rabbi David Halachmi a”h, rav of the Poalei Agudah beis medrash in Bnei Brak, was among the youthful admirers of Reb Azriel David. “We would follow him through fire and water,” he once told Zilbertzen. “And his influence extended far beyond Modzhitz. Young bochurim and avreichim from all over saw him as a spiritual guide and inspiration.”

Reb Moshe Rabinowitz a”h, who davened in the Modzhitz beis medrash in Bnei Brak, used to tell Zilbertzen, “It’s hard to explain who your grandfather was. Because as much as I explain, you still won’t understand.” Rabinowitz told him how he was one of those bochurim who used to follow Reb Azriel David around, enchanted by the singing and by his devotion.

“He told me that he used to follow my zeide with his eyes and watch how he behaved in every little matter. He told me, ‘When he opened his mouth to begin singing, even the flies were still.’ ”

Most of Reb Azriel David’s niggunim perished with those who carried them in their hearts and on their lips, and the small number of survivors who were in his circle had difficulty remembering. Aharon Zilbertzen tried to preserve whatever he could of those lost niggunim. Any time he met a Jew who knew his grandfather, he whipped out his tape recorder, even if all he could rescue were some partial fragments of songs.

“With some of the niggunim, I had a relatively easy job,” he says, “because they became a tradition in Modzhitz over the years, and it was known that Reb Azriel David composed them.”

But there were many others that weren’t passed on as Modzhitz mesorah, and Zilbertzen spent four decades gathering as many of them as he could find. A large proportion of them were preserved by Reb Berish Rosenthal a”h of Tel Aviv, a Ruzhiner chassid and admirer of Reb Azriel David in Warsaw, who would often participate in his davening and seudos. He always made an effort to memorize the new songs that would come out at every event.

“The best part, he told me, was that he would often accompany my grandfather home from shul, and one Shabbos night, Reb Azriel David signaled him to come join his seudah,” says Zilbertzen. “This was a prize that wasn’t granted to everyone. All the others joined for singing at the end of the seudah.”

Zilbertzen says he once sat at a Melaveh Malkah seudah, when he heard a chassid singing a particular niggun. “As always,” Zilbertzen remembers, “I asked him what the origin of it was, and his answer didn’t even surprise me: ‘Rav Azriel David,’ he replied, as if the thing were obvious.

“In truth, my zeide didn’t have so many melodies,” he continues. “Unlike the rebbes of Modzhitz, who would compose a dozen new melodies each year for the Yamim Noraim, my zeide only composed melodies for special occasions. Most of the people who knew the niggunim didn’t survive the war, so what’s left is what was remembered by people who were not necessarily close to him, but who were familiar with his songs or who remembered parts of tunes.”

In the Tel Aviv beis medrash of the Imrei Eish — Rebbe Shmuel Eliyahu Taub, who had been living in Eretz Yisrael since 1935 and succeeded his father, Rebbe Shaul Yedidya Elazar, as Rebbe after the Imrei Shaul’s passing in 1947 — there was a mispallel named Reb Elimelech Heibloom a”h, who owned a liquor store in Tel Aviv. “Years back, he once summoned me to his store — he told me that he had a niggun of Reb Azriel David, and that I should come with a tape recorder to learn it. I came over one day when I had some free time, and in between answering questions from customers about the price of different wines, he sang into the machine. It was a long, complicated niggun — eight stanzas — and a real prize to have it recorded by someone who remembered.

“It was a recording I cherished, but when I moved from Rechovot to Bnei Brak, somehow the tape got lost in the move. My wife and I turned the house over to find it. I couldn’t remember it, and there was no one still alive who knew it. Apparently, Hashem passed a gezeirah on that niggun.”

Over the years, Zilbertzen became a familiar figure at the tishen of the Modzhitzer Rebbes: the Imrei Eish, who passed away in 1984; his son Rebbe Yisrael Dan, a member of the Moetzes Gedolei HaTorah who moved the chassidus from Tel Aviv to Bnei Brak; and the current Rebbe Chaim Shaul Taub, a rosh yeshivah who succeeded his father in 2006. “When the Modzhitzer Rebbes would honor me with a niggun at a tish, and I began a well-known niggun of Reb Azriel David, I could see that it had a special place in their hearts. Reb Avraham Shenker, a brother of Ben Zion Shenker and the son-in-law of the Imrei Shaul, once told me after I had sung a well-known niggun of my grandfather, ‘You have no idea how often the Imrei Shaul sang that tune to himself,’ and then added, ‘and other niggunim of Rav Azriel David, too.’ ”

In 1946, when the Imrei Shaul came to Eretz Yisrael, Reb Azriel David’s son-in-law, Rav Yisrael Zilbertzen, visited the beis medrash in Tel Aviv. “Many people were in line,” his son Aharon recounts. “He waited for an hour and was then ushered in. He introduced himself as Reb Azriel David’s son-in-law — he’d never met the Rebbe before because he was a Gerrer chassid living in Warsaw and the Rebbe was living in Otvosk before escaping to America — and the Rebbe was beside himself with joy. He couldn’t believe it. He had no idea that any of Reb Azriel David’s progeny survived.”

On that same visit, the Imrei Shaul told him the saga of how the “Ani Maamin” niggun survived and reached him. “Our father told us later how the Rebbe gave him so much time, even though there was a long line outside waiting to see him, and that he told him how much he had loved his father-in-law. He saw the Rebbe a few times, and each time he got special treatment. One of those times he brought along my brother — retired judge Yitzchak Aryeh Shinhav (Zilbertzen) — who was five at the time. The Rebbe spoke playfully to this little boy, and even took the two of them up to his private room. My brother still remembers it, 72 years later.”

The extent of the love and respect the Imrei Shaul had for Reb Azriel David was expressed in a remark heard by those who were with him when the Rebbe received the news that his precious disciple had ascended to Heaven al kiddush Hashem in the death camp of Treblinka. The Rebbe exclaimed brokenheartedly, “Di velt mit Reb Azriel David un di velt un Reb Azriel David iz nish di zelbe velt — the world with Rav Azriel David and the world without him is not the same world.”

When Reb Azriel David’s death al kiddush Hashem became known in Eretz Yisrael, the Chazon Ish established his yahrtzeit as the first of Tishrei — Rosh Hashanah.

“My father, who had a kesher with the Chazon Ish, never mentioned why he made it that day,” says Reb Aharon Zilberzten. Perhaps it’s symbolic that during these days — when Reb Azriel David Fastag would elevate the olam by his singing and davening — his own holy soul is elevated every year.

Rachel Ginsberg contributed to this report

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 780)

Oops! We could not locate your form.