Those Jewish Brains

We find little to no emphasis in the Torah on Jews as being distinguished by their intelligence

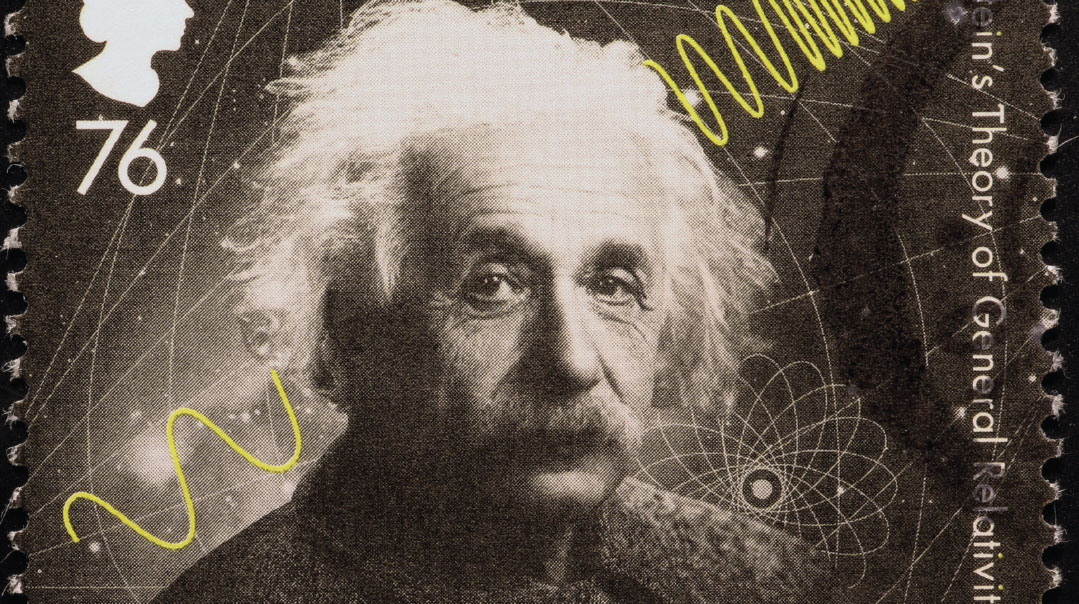

In his most recent New York Times column, Bret Stephens takes up an oft-asked question: “How is it that a People who never amounted even to one-third of one percent of the world’s population contributed so seminally to so many of its most path-breaking ideas and innovations?”

He acknowledges that the “common answer is that Jews are, or tend to be, smart,” but then poses what he calls the more difficult question of “why that intelligence was so often matched by such bracing originality and high-minded purpose.”

Stephens wants to know why Jewish genius is unique in being “prone to question the premise and rethink the concept; to ask why (or why not?) as often as how; to see the absurd in the mundane and the sublime.” Why, in other words, do Jews have an advantage of not just “thinking better [but] thinking different”?

In one brief paragraph, he lists several answers, none of which are complete or very satisfying. He cites the Jewish religious tradition that “asks the believer not only to observe and obey but also to discuss and disagree.” But the advantage of Jewish smarts has persisted in the two centuries since a large percentage, and by now a large majority, of Jews tragically abandoned Judaism. Then, he says, there is “the never-quite-comfortable status of Jews in places where they are the minority — intimately familiar with the customs of the country while maintaining a critical distance from them.” But again, that wasn’t the case for Jews who became, as the saying goes, more German than the Germans.

As for the “moral belief… that the life of the individual only has value [insofar] as it aids in making the life of every living thing nobler and more beautiful,” or the one “born of repeated exile, that everything that seems solid and valuable is ultimately perishable, while everything that is intangible — knowledge most of all — is potentially everlasting,” it’s not clear what role those beliefs would play in enabling Jews to become such radically out-of-the-box thinkers.

In a lengthy 2007 essay in Commentary, the eminent social scientist Charles Murray also addressed the origins of “the extravagant overrepresentation of Jews, relative to their numbers, in every field of intellectual accomplishment.” He accepts that this is related to heightened levels of intelligence, which leads to “the great question: How and when did this elevated Jewish IQ come about? Here, the discussion must become speculative. Geneticists and historians are still assembling the pieces of the explanation, and there is much room for disagreement.”

Starting from the premise that elevated Jewish intelligence is grounded in genetics, he sets about reviewing various explanations for how a Jewish gene pool favoring high intelligence might have come about. Ultimately, he settles on the fact that from the outset, “Judaism was intertwined with intellectual complexity. Jews were commanded by G-d to heed the law, which meant they had to learn the law. The law was so extensive and complicated that this process of learning and reviewing was never complete. Moreover, Jewish males were not free to pretend that they had learned the law, for fathers were commanded to teach the law to their children…. No other religion made so many intellectual demands upon the whole body of its believers.”

In the end, Murray admits that all the proposed explanations for Jews’ supposed smart genes simply beg the fundamental question of “why one particular tribe at the time of Moses, living in the same environment as other nomadic and agricultural peoples of the Middle East, have already evolved elevated intelligence when the others did not?”

As he brings his essay to a close, Murray (who describes himself impishly as a “Scots-Irish Gentile from Iowa”) introduces an element that even the Jewish Mr. Stephens (a former Jerusalem Post editor-in-chief) did not. “At this point,” Murray writes, “I take sanctuary in my remaining hypothesis, uniquely parsimonious and happily irrefutable. The Jews are G-d’s chosen people.”

Indeed, we are. Yet it’s interesting to note that we find little to no emphasis in the Torah on Jews as being distinguished by their intelligence. That’s not what we would expect to find concerning a nation whose status as a Chosen People has been adduced by many of our enemies as evidence of our insufferable arrogance.

If anything, the Torah castigates us, the am segulah, as at times also being an “am naval v’lo chacham — an unwise nation” (Devarim 32:6). That’s because wisdom has a different meaning in Torah than in the world at large. As Iyov tells his friends (Iyov 28:28), “Hein yiras Hashem hi chachmah — Behold, the fear of G-d, that is wisdom.”

I’m not sure what Charles Murray meant in writing that our status as Hashem’s Chosen People explains our high intelligence. But what comes along with being chosen by Hashem is that He gave us His Torah (asher bachar banu… v’nasan lanu es Toraso). In order to learn a Torah that is wide and deep beyond all comprehension, high-powered smarts are necessary, and He equipped us accordingly. Perhaps that’s the real secret of outsized Jewish intelligence.

It’s understandable that a feeling of pride fills many a Jewish heart upon hearing that 27 percent of US Nobel science prize winners and more than half the world’s chess champions have been Jews. Yet, the phenomenon of Jewish overrepresentation in creative contributions to the arts and sciences is a case of Jews using their G-d-given free will to commandeer and repurpose a gift originally bestowed for learning Torah and excelling spiritually. And thus, for all the acclaim these overachievers have garnered for us, is our nation perhaps spiritually poorer as a result? That would surely be no cause for pride.

Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 793. Eytan Kobre may be contacted directly at kobre@mishpacha.com

Oops! We could not locate your form.