This Small One Will Become Great

“We just want the brit milah, nothing more. If you won’t do it, that’s fine. But if yes, just do it and be done with it”

M

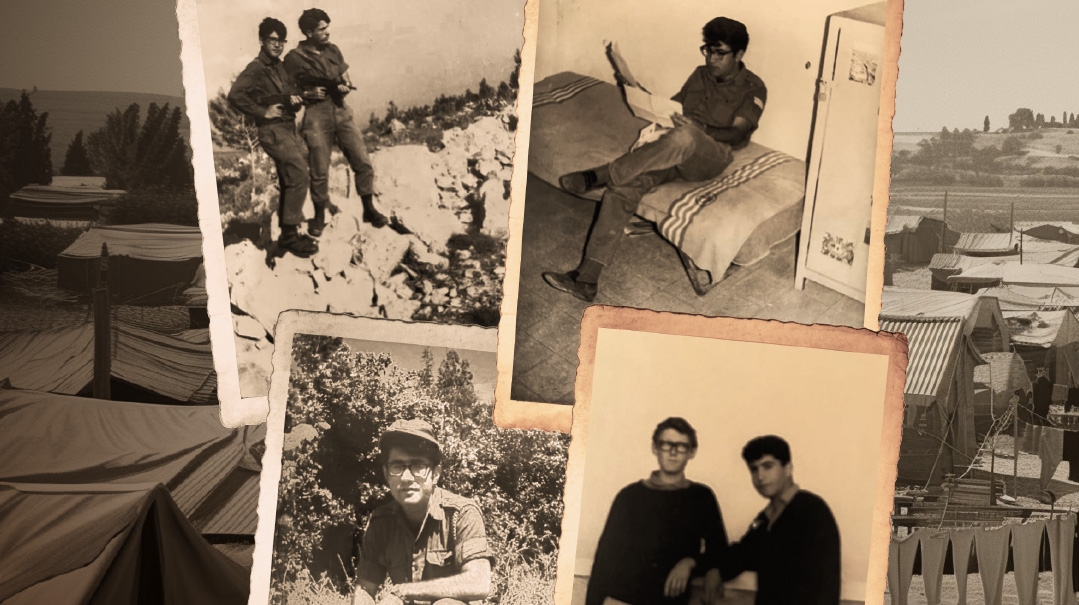

y father, Rav Refael Abuhav z”l, was best known as a cantor (he was the chazzan at the Great Synagogue of Tel Aviv for many years) but he was also a much sought-after mohel

That was in part because he performed many brissim free of charge, especially for poor families. But Abba would do more than just perform a bris, he would look after the families, often supplying them with baby supplies, food, clothing, and even money. For that reason, he had the zechus to perform many brissim across Israel.

In all the years that he worked as a mohel, one story he told us stands out.

One day, my father received a phone call from a man who introduced himself as Gideon. He asked Abba if he could perform the bris milah for his newborn son, and my father happily agreed. The bris would take place in Bat Yam, at 7:30 a.m. on the following day.

Early the next morning, my father davened at the k’vasikin minyan, as was his custom, and then took a taxi to the address he was provided. When he arrived, he was surprised to discover that the address was for an apartment building and not a shul. Though it’s not common to perform a bris in a house, it’s not completely unheard of either, so he climbed the steps and knocked on the door. A very tall man wearing a t-shirt and shorts answered.

“Excuse me,” my father said, a bit confused. “I must have the wrong house.”

“Are you the mohel?” asked the man. My father nodded.

“In that case, you are in the right place. I’m Gideon, the father of the baby. Please, come in.”

Abba walked in and looked around the empty house. “Where will the brit take place?” he asked.

Gideon led him into a side room where a newborn was sleeping peacefully.

“Right here,” he said. “In the baby’s room.”

My father was perplexed. Not only would the bris take place in a house and not a shul, but in an empty house in a side bedroom. There was also no sign of a minyan or seudah.

Trying to hide his growing unease, my father asked, “Are you expecting more people? Family members?”

“No, no,” Gideon said. “There’s no need to make a whole party out of this. We didn’t invite anyone. What for? We just want to do it quickly and get it over with. How much does the brit cost?” the man said, pulling out his wallet. “Nu, how much do I owe you?”

Instead of replying, my father looked around. “Where is the mother of the baby?”

“My wife is in the back, getting ready to leave. She has to go out. Let’s just do the brit quickly, because I also have to go. I have to be at my job at eight.”

Alarmed, Abba stared at the man. This was getting downright bizarre.

“Sir, what do you mean ‘do it quickly’? There should be guests, a seudah, a minyan…”

“Look,” said Gideon impatiently. “We just want the brit milah, nothing more. If you won’t do it, that’s fine. But if yes, just do it and be done with it.”

Abba took a deep breath. “Got it,” he said, grasping the situation. “B’seder. Don’t worry; I will take care of getting people. If you need to leave, you can go.”

The man left the house. Abba went downstairs to see if he could gather some passersby to form a minyan, but it was still early in the morning and there weren’t many people around. Abba walked back to the apartment and came face to face with Gideon’s wife. She was holding a purse in one hand and a baby bottle in the other.

She said, “Listen, I need to leave now, but the housekeeper is supposed to arrive soon. When she comes, you can leave. Here’s a bottle in case the baby gets hungry before she arrives.” And with that, she handed him the bottle and was out the door.

My father was simply in shock. Though he had performed thousands of brissim during his career he had never been in a situation like this, performing a bris alone. For a few moments he stood there just shaking his head. Then, he collected himself and began to prepare his instruments.

There was no choice, so Abba had to act as both sandek and mohel. He said the prayers quickly and then performed the circumcision. But at the point when the baby is named, he suddenly realized that the father had not given him one! What was he supposed to call him?

In a flash, it came to him:

“Vikarei shemo b’Yisrael, AVRAHAM BEN GIDEON.”

This baby was to be named for the very first person who had performed the mitzvah of bris milah, Avraham Avinu. Suddenly, his heart constricted and his eyes filled with tears. He began to cry for this poor, unfortunate baby whose parents didn’t care enough to be at his bris.

Oops! We could not locate your form.