“This is Not The Way It’s Supposed to Be”

Over the years, in both my professional and personal life, I have often heard the refrain “This is not the way it’s supposed to be.” I would suggest, in fact, that most of us (and if we were really being honest with ourselves, ALL of us), have faced a difficult or painful situation that caused us to express, to others or to ourselves, that “this is not the way it’s supposed to be”.

Of late, I seem to hear this sentiment being expressed with more frequency; and I look forward to hearing from my readers as to why they think this is so.

On the surface, the obvious response to such feelings is: “Who says it’s not supposed to be this way? On the contrary – this is EXACTLY how it is supposed to be.”

We have a basic misconception that everything is supposed to happen the way we plan it to happen, and if it doesn’t go that way, then something is wrong. In truth, events in our lives may not be in accordance with our plan, but do fit into Hakadosh Baruch Hu’s plan. Yes, it’s exactly how it’s supposed to be.

Let’s look at several examples in which I have recently heard people express the sentiment that things were not the way they were supposed to be:

A young wife and mother in our community has been dealing with a husband who began to exhibit violent mood swings. When she came to my study late one night to share her painful situation, she began with the words “it’s not supposed to be this way”.

“I married at a young age,” she explained. “My husband was a sought-after young man from a great family, and we had beautiful children. It was supposed to end with ‘happily ever after’. Sitting in a Rabbi’s study in the middle of the night, too frightened to go home and asking for advice on terminating my marriage, is just not the way it’s supposed to be”.

Around the same time, a loving father of young children who is devoted towards being mechanech his children in the best way possible (and I have personally witnessed his devotion) had to cope with a child’s emotional or mental disability. With pain evident in his tone, he approached me and said “this is not the way it’s supposed to be”.

Just recently, a young couple approached me at a Kiddush in the community and excitedly shared the news that after some difficulty, they were Boruch Hashem expecting a child. No more than two weeks later they came to my home to share their pain: initial tests showed significant developmental concerns with their baby. Together they protested: “But Rabbi, this is not the way it’s supposed to be”.

If these few stories have still not brought the point home, please allow me to share a personal story. Almost two years ago, my wife and I were overjoyed at the birth of our first grandchild, a beautiful baby boy. Within hours, we were forced to deal with what has become a difficult ordeal, watching our beloved grandson endure struggle after struggle. (If you derive Chizuk from this article, may it be a zechus for the refuah of Alter Chanoch Henoch ben Ilana Yocheved).

Within those first few days of coming to grips with what we were facing, we divided up the hospital shifts among us. I accepted a long Friday night shift in the neonatal ICU at North Shore Hospital, sitting with my grandson as he was fighting for his life. Around 3 AM, one of the doctors on call, a wonderful young orthodox wife and mother from Teaneck, NJ, on a 24 hour shift that weekend, came over to talk.. She became personally involved in our grandson’s medical care and had grown especially fond of his parents (my daughter and son-in-law). She discussed the baby’s critical state and the methods of care that they were providing. Then, as she took leave of me, she stopped, broke down in sobs and said,”Rabbi, it’s not supposed to be this way”. Then she left me alone with my thoughts. I thought a long time about her heartfelt words and what would be (or should be) my response. Here are some of those thoughts.

As we look around us, we see a lot of tzaros. It seems that everyone has some stress or pain in their lives. From shidduchim to shalom bayis, from parnasah to health issues, the list goes on. Why? Because Hashem challenges people to see how they cope and whether they use those difficulties to grow stronger and better.

An impoverished Yid once traveled to Radin to ask the aged tzaddik and gadol hador, the Chofetz Chaim ztz”l for a bracha for parnasah. He began by remarking “Would it hurt if only I had it a little easier?”

“How do you know that it wouldn’t hurt you if you had it a little easier?” the Chofetz Chaim objected. “Hakadosh Boruch Hu, our beloved Father, is kulo rachamim – completely compassionate. Don’t you think He wants to make it easier for you, and that He has the ability to do so? Obviously, the reason He doesn’t do so is because for now, these are the best circumstances for you to be in. You have every right to daven and ask for better, but you cannot say that it wouldn’t hurt you to have more.

I remember hearing from Rav Shach ztz”l – on more than one occasion – that if he would write down all the tzaros he had in his lifetime in a sefer, it would be much thicker than his “Avi Ezri” (Rav Shach’s magnum opus, a multi-volume set on the Rambam).

Rav Moshe Sternbuch shlit”a often relates that he was once walking in London with his beloved Rebbe, Rav Moshe Schneider ztz”l, several years before the war. An older talmid was getting married in the United States, and he came to take leave of his Rebbe and asked him for a bracha. Rav Schneider replied, “What would you like your bracha to include?” The talmid replied “A life without problems.” Rav Schneider replied, “That’s not a bracha. There is no such thing as a life without problems. Rather, you should ask for a bracha that you will be able to overcome the challenges that Hashem sends you.”

And so, when we are faced with challenges, disappointments, setbacks or difficulties, it is obviously that it is supposed to be that way. Our responsibility is to face them, try our best to deal with them, and, most important of all, grow stronger from them.

How does one do that? By seeing the positives in every negative. By seeing the sunshine in the middle of a dark and gloomy day. Rav Tzadok Hakohen sees this responsibility in the very laws of nature. Night comes before day; dark storm clouds fill the sky before we are blessed with rain. We each have to experience a spell of darkness before we see the light.

In an address at an Agudah convention, Rav Noach Isaac Oelbaum shared a thought that he heard from Rav Simcha Wasserman ztz”l. Rav Simcha said that in his youth, he once witnessed sunset on one side of the sky, and sunrise at the same time on the other side of the sky. The metaphor is that this is the way a Torah Jew looks at things in his of her life! The sunset and sunrise can occur at the very same moment, and we must be able to see and feel the light amidst the darkness.

When we finally grasp this concept that it’s SUPPOSED to be this way, because Hashem placed this challenge before us and we need to overcome it; it will help us understand when we should rely on faith, and when and where to concentrate our efforts. As the Lakewood Mashgiach, Rav Matisyahu Solomon, shlita, explains, “We need to put less faith in our efforts and more efforts in our faith”.

The Medrash Raba (Parshas Veyeira 55:2) discusses in great detail the story of the Akeidah and how Hashem was testing Avrohom Avinu. After citing posuk in Tehillim (11) that Hashem always challenges the righteous person and provides him the opportunity for great spiritual growth, the Medrash offerss 3 parables:

The first is of a person who wants to perfect a new garment made of flax. The way to insure its strength and endurance is by banging on it with a stick to smooth and stretch it to perfection. Now, if the garment would be weak, the banging would rip it to shreds, so he chooses only the strongest and sturdiest garment. Similarly, Hakadosh Boruch Hu selects only the best and strongest people to challenge – those he knows will become better from those nisyonos.

The second parable is of a craftsman making a vessel to use over fire. He doesn’t use the weak vessels, because hitting it with the anvil would shatter it to pieces. Instead he selects the strongest one and bangs on it to perfect and strengthen it. So too, Hashem chooses a Tzadik, who is strong and steadfast, and can withstand the banging of the anvil and, subsequently, the heat of the fire.

The third and final parable is about a person who had 2 cows, one weak and the other strong and healthy. When he needs an animal to carry a heavy load, he places it on the healthy cow. So too, Hashem selects the spiritual healthy tzaddikim, who are most able to carry the great burden.

But why does the Medrash have to give three parables to convey the same message?

A deer friend, Reb Shmuel Unger, pointed me towards the Dubna Maggid’s illuminating explanation of this Medrash.

There are three types of nisyonos, explains the Dubna Maggid. The parable of the garment alludes to a test that is for the person himself, a challenge that enables one to attain personal growth, for when you bang on a garment of flax, no one hears it besides for the person himself. It’s his personal nisayon.

In the second parable, banging on a vessel is cacophonous and can be heard by all that are within ear shot. That’s a nisayon from which the others can gain insight and inspiration along with the person who is being tested.

In the third parable, the cow derives absolutely no benefit from the load that it carries. The burden benefits only the owner, who gets his wares to his destination. This type of nisayon doesn’t benefit the Tzaddik who is afflicted; it’s merely an opportunity for the owner, the “Baal Habayis” of the universe, to bring merits to Klal Yisrael. Hashem chooses a “strong and healthy cow” upon which to place his burden, one who He knows will indeed bring zechusim to Klal Yisroel.

When we are afflicted with tzaros, we are not privy to which of the three parables our troubles represent. But we do know that Hakadosh Boruch Hu is challenging us to become stronger and grow from them. In the words of Rav Yitzchak Hutner (Pachad Yitzchak – Michtavim), the level that a person can attain through his or her personal Akeidas Yitzchak far surpasses any level that can be reached through other means.

Clearly, no one desires to have nisyonos or tzaros in their lives. But when they do hit, we must appreciate that “This is the way it’s supposed to be”.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha Issue 337)

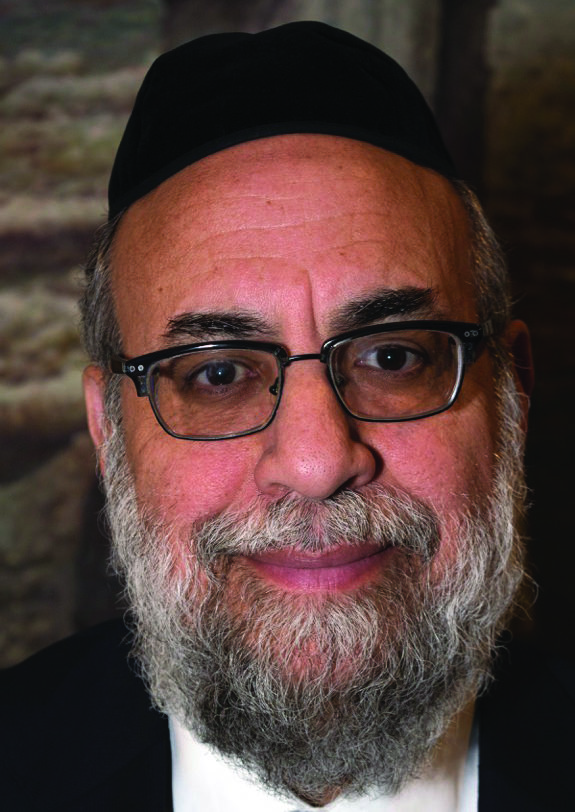

Rabbi Aryeh Z. Ginzberg is the rav of the Chofetz Chaim Torah Center of Cedarhurst and the founding rav of Ohr Moshe Torah Institute in Hillcrest, Queens. He is a published author of several sifrei halachah, and a frequent contributor to many magazines and newspapers, where he writes the Torah hashkafah on timely issues of the day. He is also a sought-after lecturer on Torah hashkafah at a variety of venues around the country.

Oops! We could not locate your form.