There’s Always a Solution

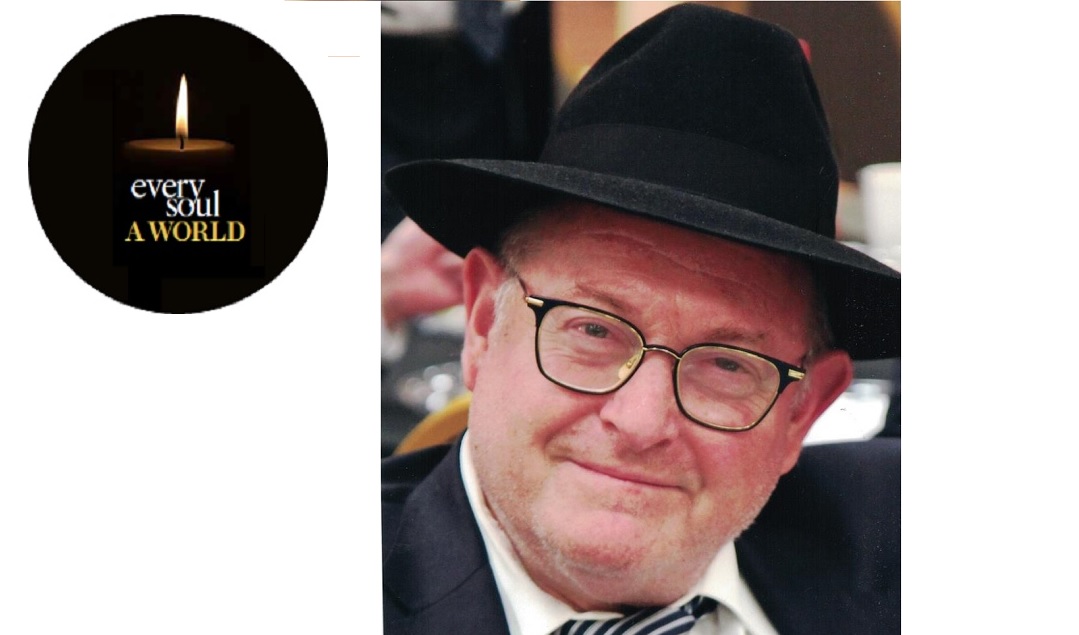

For proof of the adage that greatness comes through struggle, one need not look further than Dayan Westheim

V

isit a grocery in the US or open a fridge or cabinet in Israel, and you’re almost guaranteed to come across something, from yogurts to novelty candies, bearing the stamp of Igud Rabbonim, better known as “Rav Westheim’s hechsher.”

Largely thanks to the exacting halachic standards of Dayan Osher Yaakov Westheim, who suddenly passed away last month, a hechsher operating out of modest offices in provincial Manchester, UK, created a world-wide reputation and something of a global kashrus empire.

But Dayan Westheim’s petirah sent shock waves far beyond the kashrus world.

Only in England, with its history of central batei din headed by Torah giants such as Rav Yechezkel Abramsky and Rav Yitzchak Yaakov Weiss, the Minchas Yitzchak, does the title “Dayan” have such resonance, implying a rav, posek, and leader recognized across the community and beyond.

Heir to this title was Dayan Westheim, whose vast Torah knowledge, warm heart, and unusually technical mind made him a beloved mainstay of Manchester’s Jewish community and the global kashrus industry for decades.

“He was a person who thought out of the box with kashrus, and would say that the chochmah is not to find problems, but to find solutions,” says his son-in-law and successor at the hechsher, Rabbi Shulem Landau. “Besides his Torah and phenomenal memory, he was blessed with the gift of being able to find the right thing to say to each person, whether it involved shalom bayis, a personal crisis, or sensitive medical question.”

At a time when different streams of mesorah were far more segregated, Dayan Westheim, or Reb Osher, as talmidim knew him, was a self-made person, who chose his unique blend of different paths in avodas Hashem. That, and an upbringing on both sides of the English Channel (or “La Manche,” the French variation, as he referred to it when I met him before my bar mitzvah), gave him fluency in different languages, and currency with a wide range of people.

But what defined his rabbinic career was his open door. Even when he was forced to set fixed visiting hours in later years, he couldn’t turn a visitor away. “What will I answer in the World to Come,” he would say, “if I make a person wait?”

Merged Messages

For proof of the adage that greatness comes through struggle, one need not look further than Dayan Westheim. At age seven, he moved with his family to Paris, where his father, Rav Aharon — an early Gateshead Kollel alumnus — took a position at the historic Franco-Yekkish Rue Cadet community. That relocation gave him the language skills he went on to use in his kashrus travels, but it also meant a very early separation from family.

With Torah schooling in Paris not up to the standards that his father wanted for him, 11-year-old Osher Yaakov was sent alone to Gateshead boarding school. He had no relatives in the town and was able to come home only once a year for Pesach. “He didn’t speak about it, but it can’t have been easy,” says his son-in-law Rav Shulem Landau. “Perhaps his ability to feel for others came from this experience.”

When a family member once asked him, “Who are you?” Dayan Westheim replied, “The chassidim think I’m litvish, and the litvish think I’m chassidish.” That unique blend began to develop through contact with chassidic bochurim in Gateshead Yeshiva.

“Dayan Westheim once said that being away from home, he missed out on the warmth of his family yet found a replacement with chassidus,” says Rabbi Yehoshua Aharon Sofer, rav of Beis Yisroel, Manchester, and a close talmid.

But that wasn’t a path that Rav Aharon Westheim — originally from Frankfurt, and then a product of the pre-war Gateshead yeshivah and kollel — wanted his son to follow. “When Dayan Westheim started to become drawn to chassidus, his father was upset and sent him to Beer Yaakov, a real litvishe yeshivah headed by Rav Moshe Shmuel Shapira and Rav Shlomo Wolbe. In the end it didn’t really help, but that’s why he was able to bridge so many worlds,” says Rabbi Landau.

One of those worlds was that of Biala, a chassidus headed by Rebbe Yechiel Yehoshua Rabinowicz, known as the Chelkas Yehoshua. This dynamic rebbe survived the Siberian labor camps, immigrated to Eretz Yisrael in 1947 and lived in Tel Aviv; he served on the Moetzes Gedolei HaTorah and was one of the founders of Chinuch Azmai. The young bochur from England was drawn to the Rebbe, and the Rebbe — seeing something special in this outwardly litvishe bochur — drew him in. Years later, when Dayan Westheim was establishing himself in Manchester, the Biala Rebbe would send him long air-mail letters filled with Torah – an unusual sign of the close bond between the two.

Although he left his rebbe in Eretz Yisrael, Dayan Westheim encountered his halachah rebbi muvhak in Manchester, where he headed next to join the kollel even before he was married.

Dayan Weiss, as the famed author of the Minchas Yitzchak was known locally, was head of the Manchester Beis Din and the Kollel Rabbanim until he headed to Jerusalem’s Eidah HaChareidis in 1970. “Dayan Weiss saw that Reb Osher had kochos, so he told him to learn shechitah and then brought him into the kashrus department of the beis din,” says Rabbi Landau. “There are a lot of teshuvos in Minchas Yitzchak to my father-in-law, and he quoted Dayan Weiss all the time.”

Those years completed Dayan Westheim’s rise to becoming a well-rounded talmid chacham, aided in no small amount by Dayan Westheim’s own prodigious memory and his appetite for hard work.

“His main strength in learning was a phenomenal memory,” says Rabbi Landau. “He inherited that from his father, who never had a phonebook and remembered hundreds of numbers.”

He also learned to live on very little sleep. “He said once that he taught himself a breathing technique that enabled him to sleep less at night. He slept three to four hours a night, and on Friday night he rarely slept at all,” Rabbi Landau relates.”

Out of the Box

Most people’s involvement in the kashrus world begins and ends with a glance at the food packaging. But for those involved in the global supply chains that bring kosher food from field and factory to our tables and plates, kashrus demands an unusual blend of Torah knowledge and real-world expertise.

Dayan Westheim’s involvement in kashrus reflected his belief that people should be able to have affordable food without compromising on their standards. And with his technically agile mind, kashrus was a natural fit.

“He was a world expert in out-of-the-box thinking when it came to kashrus,” explains Rabbi Danny Moore, kashrus director at Badatz Iggud Rabbonim.

“Very often companies would try to get a hechsher from big names in the kashrus world, and would be told that some of their machinery couldn’t be kashered, for example. That happened to a baby-formula manufacturer in Ireland, who went through multiple kashrus agencies until they heard of Dayan Westheim. He came, quickly grasped the manufacturing process, and then drew up a solution on the back of an envelope.”

Another example of his solution-oriented approach, says Rabbi Moore, involved the French wine industry. “In the south of France, industrial water is expensive, which has led some hechsherim to forgo the milui v’irui emptying-and-refilling method of kashering of the giant storage tanks, because the companies are unwilling to waste 300,000 liters of water. His solution was to fill the tanks with giant balloons, meaning that you only need 20 percent of the water volume to achieve the same thing.

“Walking round the factory,” continues Rabbi Moore, “he would be deep in thought. ‘I’m thinking how the Minchas Yitzchak, or my mechutan Rav Wosner, would kasher this piece of machinery,’ he once told me.”

Dayan Westheim’s global kashrus reputation wasn’t at the expense of his deep involvement in other areas of halachah and communal affairs. As an expert in medical halachah, he was instrumental in helping many distressed couples. Accompanying him to a kiddush one Shabbos, Beis Yisroel’s Rabbi Yehoshua Aharon Sofer remembers Dayan Westheim telling him, “This bar mitzvah boy is here today because of the advice I gave to the family.”

And as someone with a proactive nature, Dayan Westheim didn’t just answer question. He got behind numerous communal initiatives. For example, seeing the struggles of some bochurim in regular yeshivos, Dayan Westheim founded and fundraised for Yeshivas Ezras Torah, a pioneering effort to cater to those bochurim and their specific needs. “Amazingly,” says Rabbi Landau, “he had no personal gain from it. He wasn’t the rosh yeshivah — he just felt that there was a need to help struggling bochurim.”

Broad Mind, Warm Heart

My own pre-bar mitzvah audience with Dayan Westheim came about through his personal connection with my father, Rabbi Jonathan Guttentag. As a young rabbi in the 1980s in Southport, an out-of-the-way seaside town 50 miles from the Manchester Jewish community, my father often contacted Dayan Westheim, who was “extremely personable, sensitive, and totally gave himself over” to whoever was asking a question or needed his assistance.

Dayan Westheim dealt with the halachic ramifications of moving my great-grandfather from his burial place in Northeast England to Israel — which prompted a teshuvah in Rav Shmuel Wosner’s Shevet Halevi about “the niftar, Gedalia David Guttentag of Newcastle.”

It was the Dayan’s unusual understanding of people beyond Manchester’s then-small chareidi community — perhaps due in part to his unusual multilingual childhood — which drove him to take initiatives beyond his own communal borders.

One was the Whitefield mikveh, a novelty in the middle-of-the-road Manchester Orthodox community, my father’s next stop after Southport. “Dayan Westheim removed his rekel and clambered inside the boros to inspect them,” my father recalls. “He was instrumental in bringing the Manchester chareidi community, including the Manchester Rosh Yeshiva, to the opening of the mikveh.”

Another pioneering effort that Dayan Westheim backed was the creation of the Whitefield Kollel, a trailblazing outreach kollel along American lines. “For ten years he was rosh kollel of the morning chaburah, known as Kollel Nachalas Dovid, because he believed that avreichim should spend the last hour of their day learning with balebatim,” says my father, Rabbi Guttentag.

That ability to understand different parts of a broad community was reflected on a Manchester WhatsApp group in the wake of Dayan Westheim’s petirah.

“A few years before my wife and I moved to North Manchester we went to see Dayan Westheim,” one post read. “We wanted to make our kitchen kosher, and he listened to where we were coming from, then told us what to do in detail. We later realized that because we were baalei teshuvah he was lenient on some of the things he told us. He didn't want to put a stumbling block in our way.”

Understanding where each person was coming from meant that he had patience for everyone, young and old. “I remember once being in Dayan Westheim’s study and two little children came in with a paper plate sent by their mother,” recalls Rabbi Yehoshua Aharon Sofer. “Can the Dayan check if there is starch in the plate?” they asked, and very patiently he stopped what he was doing and took his trusty old bottle of iodine, diluted it with some water, and checked the plate.”

A Rabbi’s Rabbi

Besides for his all-encompassing rabbinical and kashrus duties, the Dayan served as a source of inspiration and guidance for two generations of younger rabbanim. He was, said Rabbi Guttentag in a widely quoted reaction, “a rabbi’s rabbi.”

“When I first came to Manchester 30 years ago,” says Rabbi Yaakov Wreschner, a leading rav in Northwest Manchester, “he was the address for anything that needed Torah and broad knowledge of the world. He was the first to deal with infertility, he had connections to police and social workers for abuse cases, he was the only address for dealing with Choshen Mishpat cases — able to handle both the halachic and legal aspects.”

In his unassuming way, Dayan Westheim passed on the mesorah of rabbanus to the next generation. “Most of Manchester’s rabbanim received their shimush from Dayan Westheim,” said Rabbi Sofer. And as a leading community-wide rabbi himself, he understood the unique balance a community rav needs to find between optimum halachah and practical implementation.

“When the eiruv was completed in Manchester,” says Rabbi Sofer, “there were some talmidei chachamim who were more stringent and wanted the Dayan to take into account the opinions of more poskim. Dayan Westheim told me at the time that there is a difference between a kehillah rav and a talmid chacham. A community rav needs to figure out how to alleviate the challenges and difficulties of his kehillah — he needs to understand how challenging it is for the women and children to stay at home, very often in small apartments, for the whole Shabbos. Others can take stringencies upon themselves, but the rav must understand the kehillah’s needs and know upon which poskim to rely upon.”

No Easy Way

About three months ago, Dayan Westheim suffered a bout of pneumonia and his sister from Eretz Yisrael called him. “Why don’t you take it a little easier, and cut back on your obligations and projects?” she asked. He replied, “I now take a short nap at the end of the morning so I have strength for the evenings, but there is too much to do and no time to take it easier.”

That attitude of service is perhaps the main part of his legacy. As his son-in-law Rabbi Shulem Landau says, “He gave himself away for other people. Over the last few years he had health issues, but that never stopped him from opening his door — he just loved Yidden.”

Perhaps there’s no better tribute than the words of a member of Dayan Westheim’s shul: “My husband is a Kohein, and on Yom Tov when it’s time to duchen, all the little boys in shul go under their father’s tallis, but what do the young boys whose fathers are Kohanim do?

“My sons had another father in shul who took them under his tallis. His name was Dayan Westheim. He was so totally humble, so caring and yet so great. I still can’t begin to fathom what we’ve lost.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 809)

Oops! We could not locate your form.